Premium Subscribers can access the audio version here

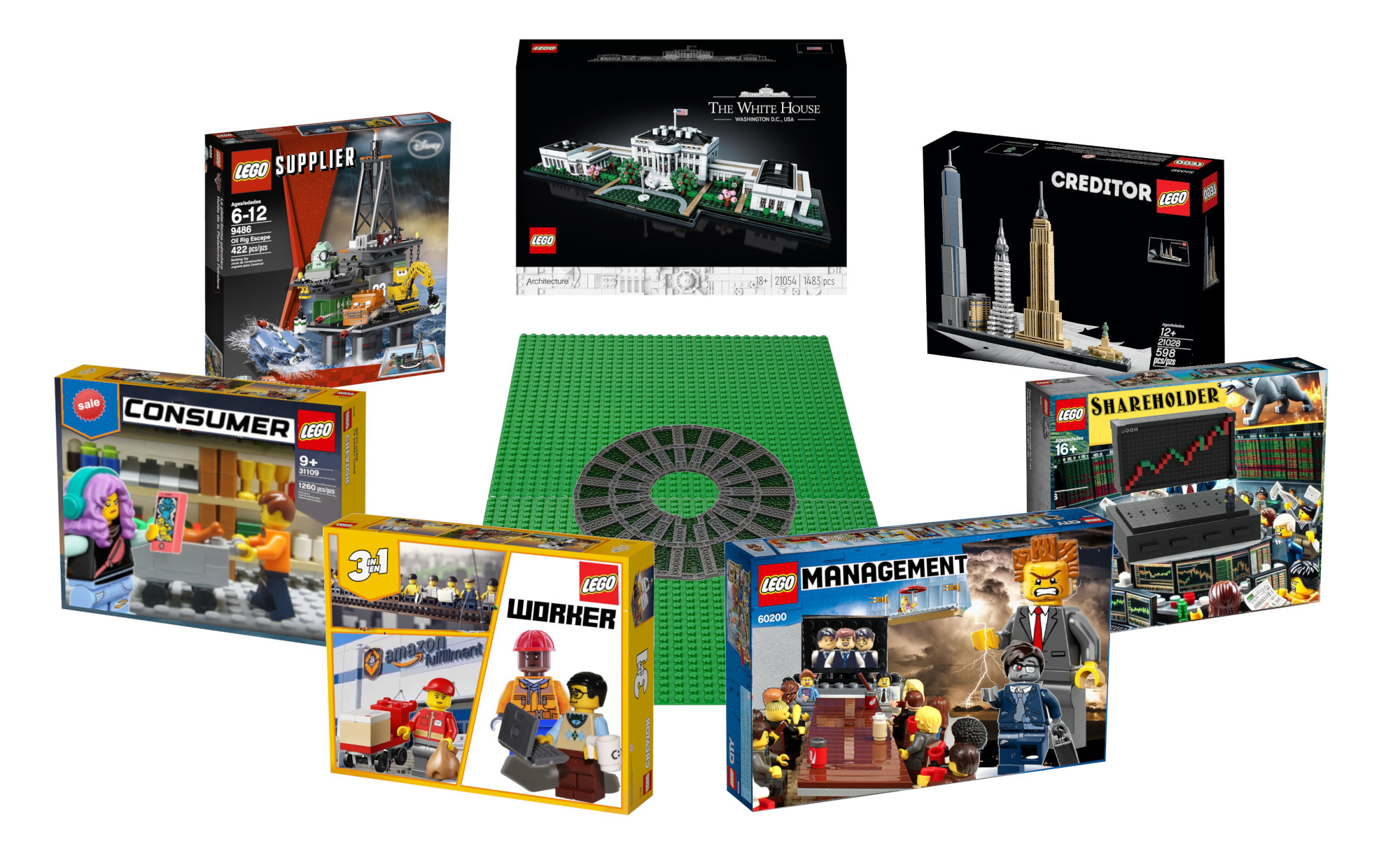

I adored Lego as a kid, and now I have a fantasy about approaching the Lego company to propose a new thematic line. My proposed series, which will be called Lego Corporate Capitalism, will help kids understand the economy they’re born into. It will come as 7 box sets that fit together, with scope for loads of expansion sets.

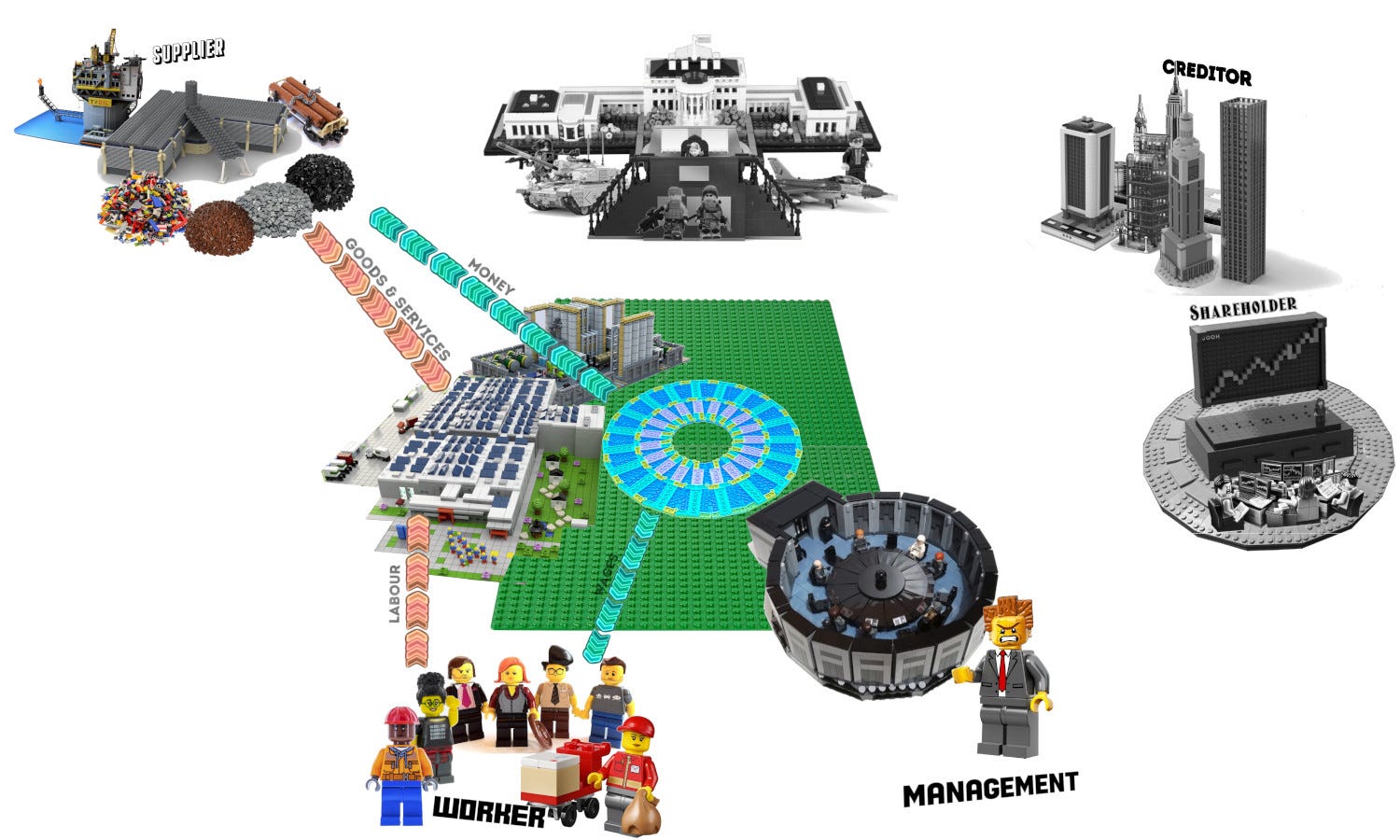

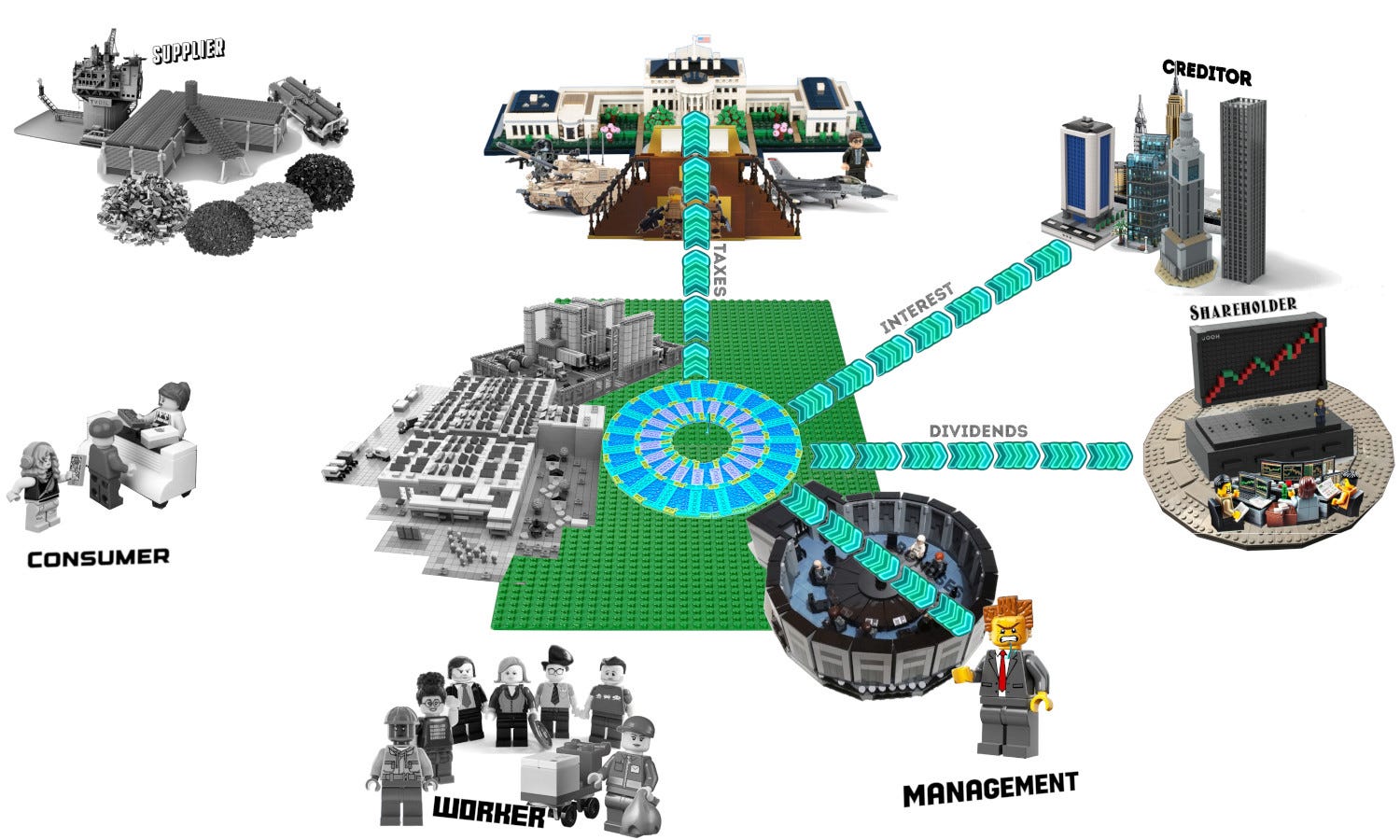

There’s no beginning or end to corporate capitalism. It’s a fractal and circular system where the outputs of one part are inputs to another. We touch different parts of it every day, but it’s difficult to see in its entirety. That’s why providing kids (and adults) with a simplified tactile version of it would be useful. Let’s begin with the base set.

The Starter Pack

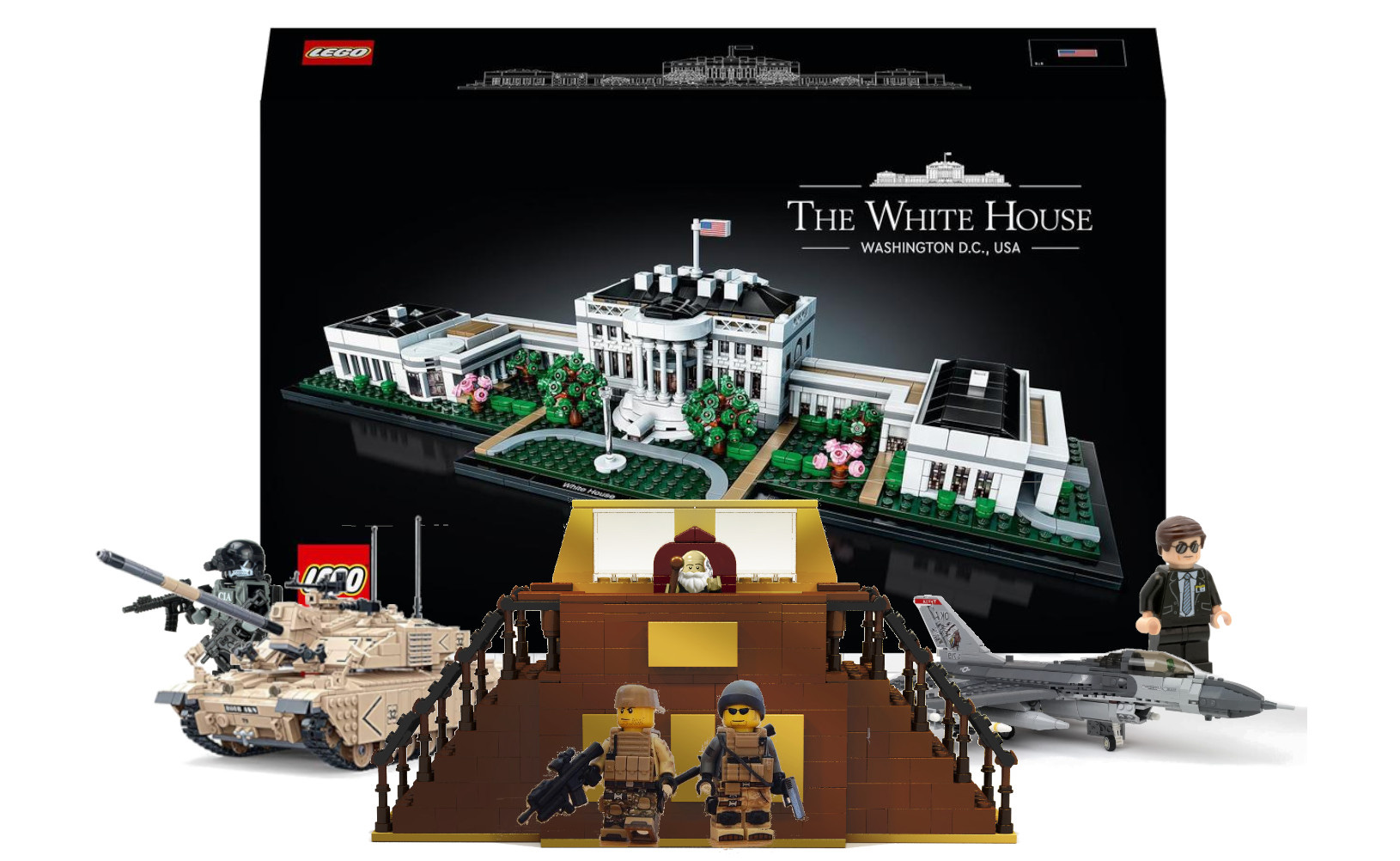

I was born into the 1980s when state-versus-market rhetoric was at an all-time high. By this time, free-market theorists had popularized the idea that the public sector made the private sector weaker, but in reality there’s no such thing as large-scale capitalism without large-scale nation states. The world’s most powerful companies reside in the world’s most powerful states, and, inversely, the world’s weakest ones reside in the weakest states. Modern markets are underpinned by a public sector substrate, and corporate and state power are a symbiotic unit. So, the Lego Corporate Capitalism starter set must contain a basic collection of state institutions, with military, law courts and CIA agents.

When you step out into the economy, you’re not stepping out into a lawless void. You’re stepping into a forcefield of private property rights backed by state power and connected together via state infrastructure, roads, money systems and so on. We’re going to abstract all of that into a green state base-plate, like this.

This base plate forms a foundation to lay out a new corporation. At the beginning of humanity, there was no such thing as a corporation. You’d have groups of people that might act together, and they might give their group a name, but nobody was under the illusion that the named group existed separately from its underlying people. Modern laws of incorporation, however, sever this connection. Corporations are a creature of law, artificial legal entities that are seen to have ‘personhood’ in themselves, such that they can exist independently of the people that activate them (i.e. those who work for them or direct them). At the core of corporate capitalism, then, are a series of hollow shells, empty legal vessels with no soul that act as centre points around which all the players will gather.

The Lego Corporate Capitalism starter set comes with a circular representation of one of these corporate entities. It’s hollow centre can be filled up with a logo and a name. For now, let’s just call it Hollow Shell Inc.

Now we can pretend that this thing has personhood and can do stuff. You’ll see this fantasy in action every time you see a news item that says ‘Pfizer releases new dieting pills’, or ‘Microsoft starts a new AI unit’ or ‘BP invests in Turkmenistan’. These entities are being spoken of as if they have agency in themselves, but BP is a conglomeration of over 67,000 people (not to mention hundreds of thousands of others involved in its supply chain), but ‘it’ is spoken of as if it were a big giant walking around. In reality, Hollow Shell is just a fulcrum point for thousands of actual human beings, and it will do nothing unless they turn up. To get them to turn up, however, it needs to be capitalized.

The Finance Editions

To be able to act in the world, Hollow Shell needs a bank account, but that account will initially be empty. Capitalization is the process whereby the empty corporate vessel’s account is charged up with money - like charging up an empty battery - and the financial sector is where we go for that.

The mainstream financial sector is largely constituted by commercial banks, investment banks and mega funds (e.g. pension funds, insurance funds, sovereign wealth funds, mutual funds, hedge funds, private equity funds and venture capital funds), all of which operate within a multi-layered monetary system underpinned by central banks (I write a lot about that monetary system on this site, so I’m not going to focus on it in this piece). One basic role of the big funds is to pool the money of various smaller players - such as pensioners - and one basic role of the investment banks is to then corral these funds into capitalizing corporations. When doing this, the big funds can take on two basic personas: shareholders (equity investors) or creditors (debt investors).

Shareholder Edition

Shareholders - or equity investors - are institutions and people that will give money to Hollow Shell in exchange for an ownership stake in it (a share) that will enable them to claim a slice of its profits in future. If Hollow Shell does well, they’ll do well. If it does badly, they’ll do badly.

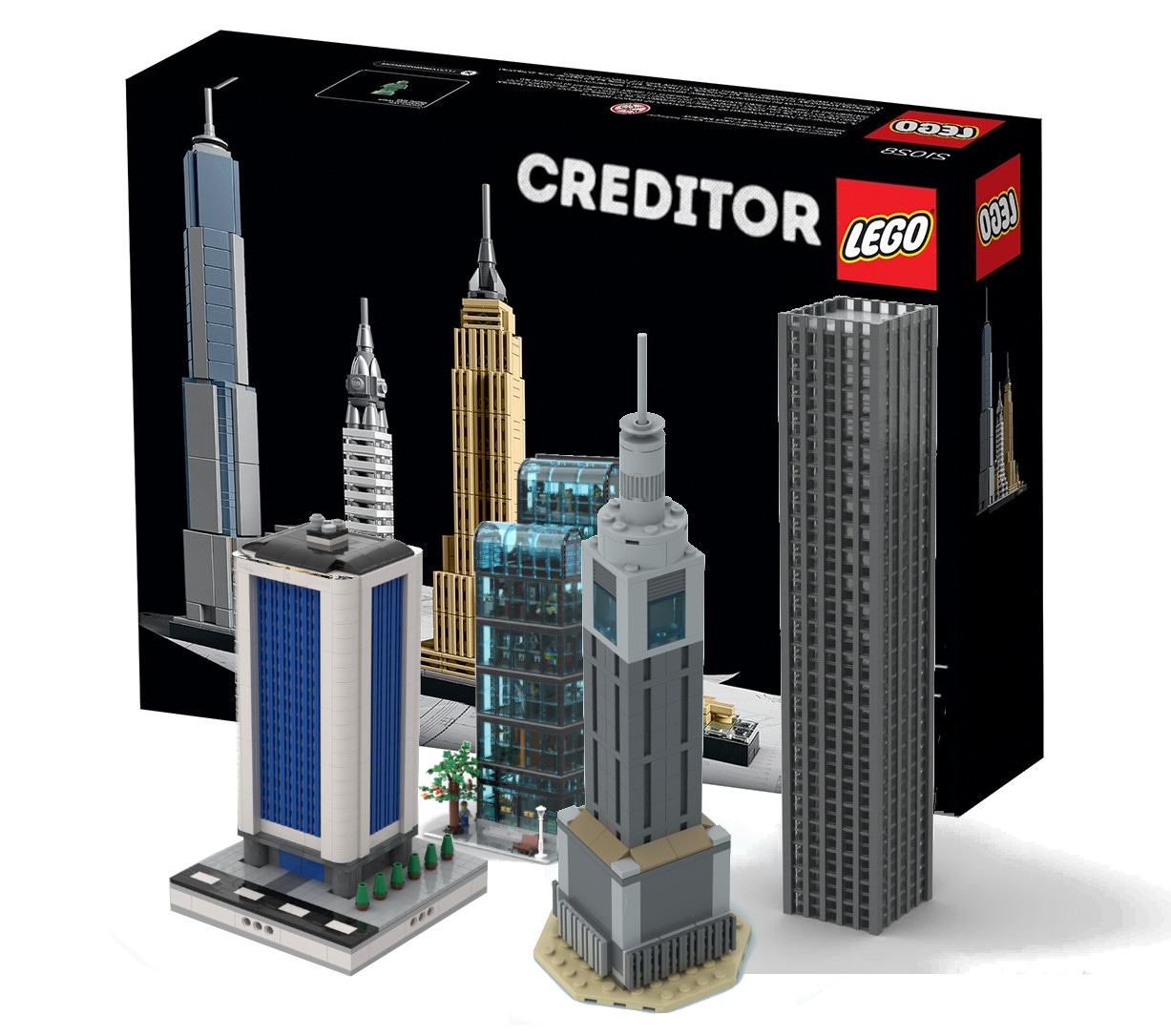

Creditor Edition

Additional financing can be secured from debt investors, otherwise known as creditors. These are people and institutions that will grant money to Hollow Shell in exchange for a contract that entitles them to a fixed stream of future interest payments regardless of how well the company is doing. If the company’s fortunes skyrocket or plummet, the creditor’s claim remains constant.

Creditors include bondholders, but also banks. In a more advanced future version of the Lego Corporate Capitalism line, banks will get their own edition, because - unlike other creditors - they have money-creation power (i.e. when ‘lending’, they’re issuing money). For now, though, let’s just lump bondholders and banks into a single category.

The basic finance game

The two classes of financier above give the same thing - money - in exchange for the same thing - a contract for future money, but their terms are slightly different. The creditors demand a fixed amount back in future, while the shareholders get the right to a fluctuating amount, so take on more risk in exchange for the potential to get a massive upside if the firm does really well. There’s a whole world of financial engineering that can be done by combining these classes of financier into weird combinations, or playing them off against each other. For example, shareholders can use creditors to amplify their returns (‘leverage’), while creditors use shareholders as cannon-fodder to take losses. Regardless, these classes of financiers collectively ‘charge up’ Hollow Shell with money.

The Manager Edition

Hollow Shell has now had its bank balance charged up, but it’s a legal entity with no mind, body or desire, so it’s going to need some management before it can start using that money to buy stuff. The Lego Manager Edition gives you get a whole host of potential managers that can be hired. The set comes along with a management conference room that docks into the corporate shell to take the controls. Once in place, the management team can use Hollow Shell’s bank balance to buy assets, like facilities, cars, machines, land, IP rights, datacentres, and so on.

The Worker Edition

Managers set strategy, make decisions and direct Hollow Shell to buy assets, but it’s not like they’re going to work the machines, code the software, or drive the cars. So, the next major task for the management team is to direct Hollow Shell to hire workers to do that stuff.

In our economic system, corporations often act as gatekeepers to production. They have priority access to financial markets, and use those to get money to buy up assets that workers must then try get access to. When you’re applying for a job you’re essentially competing with other workers for the right to activate a company’s assets (or to access the means of production). The Lego Worker set comes with a range of proletarians who can be made to fight each other for the right to survive.

A few hundred years ago, these workers might have been slaves, in which case they’d also be considered assets of the company, but nowadays workers are tethered to the corporate shell by labour contracts. Once they’re in position, the bosses can boss them, getting them to activate the assets (e.g. by getting on the computers, or in the factory, or doing whatever it is that the company does).

Hollow Shell will never do anything unless workers activate its assets, so corporate profits stem just as much from workers as they do from financiers or managers. We’re used to hearing billionaire shareholder-CEOs claim that they ‘create jobs’, but in it’s equally valid to say that all those jobs ‘create billionaires’, and enrich the financial sector. This is because the shareholders, creditors and managers will literally make nothing unless the assets owned by Hollow Shell are actually operated by somebody.

The workers get paid relatively small fixed sums (wages, salaries) to operate the assets, which is what the shareholders are relying upon in order to extract what Marxists would call ‘surplus value’. The reason why Jeff Bezos makes $35 million per day is not because he does any work. It’s because he owns the shares of the hollow shell that owns the assets that are activated by Amazon workers, those people in the warehouses and the drivers who turn up at your door.

This is a major source of class struggle. One of the great chain-reaction battles in capitalism occurs when shareholders pressure managers to extract profits, which makes them attempt to drive down wages and to replace workers with machines. This is one reason why managers love to automate (unless the automation threatens their own jobs, which - in the age of AI - it’s now doing).

The Supplier Edition

Hollow Shell doesn’t internalize all its operations. Large parts of its production processes will be outsourced to other companies (also hollow shells with managers controlling workers). We call these suppliers, and they form the supply chain. Sometimes these supply chains are rigid, fixed in place by long-term contracts, and at other times they’re fluid. The Lego Supplier Edition is a bonanza of components, services and goods that can be inputted into Hollow Shell’s production. This means production now takes place using both internal and external workers.

Corporate capitalism is an ecosystem, with mega corporates serviced not only by other corporates, but also by thousands of smaller SMEs and individual contractors. ‘B2B’ (business-to-business) firms specialise in being suppliers, providing components or services to other businesses, and never touching ‘the consumer’ (who we’ll meet below). All these supply chains can double over each other and get entangled: a car company might input plastics from a plastics company, which inputs petroleum from an oil refining company, which inputs both cars and plastics outputted by the previous two companies.

These supply chains are also a major frontline of economic politics. For example:

Managers can intimidate their local workers by threatening to outsource to foreign suppliers with foreign workers. Alternatively, they can buy machines from an external supplier to replace workers. That machine will be made by other workers, but sold from hollow shell to hollow shell at the order of the managers, who are essentially getting workers to indirectly undermine each other like this

Worker contracts are normally long-term, but managers can erode that by turning the workers into freelance ‘suppliers’ or external contractors instead of employees. Companies like Uber, for example, will call it’s workers ‘partners’ or ‘entrepreneurs’. Uber drivers do exactly the same job as a driver employed by a taxi company, but without a fixed contract or wage. In exchange for losing job security, they have the option to not turn up to work, but on average Uber knows that they will (and the workers are incredibly replaceable)

The Consumer Edition

Workers, whether employed by Hollow Shell or its suppliers, will collectively bring goods and services to life, but the products they produce are not owned by them. They are owned by Hollow Shell, and for it to extract profit it needs to sell those goods. The Lego Consumer Edition is where the back end of capitalism meets the front end. It provides a range of consumers, people who browse around in shops or online, looking to buy stuff.

In mainstream economics, the consumer is often casually imagined to direct the global economy through their buying choices, like little entitled brats that force managers to do their bidding. In reality, consumers have far less power than is often attributed to them, and are also often abused in various ways and infantilized by marketing. They supposedly make free choices, but in reality are also coerced by various systemic forces into endless consumption, and often have to buy stuff to keep up with an accelerating economy that threatens to ‘leave them behind’ (See Tech Doesn’t Make Our Live’s Easier. It Makes them Faster).

As they hand money over, the product or service - at least in theory - detaches from the corporate entity and enters their ownership. I say ‘in theory’, because nowadays the product often remains attached to the company in some way, like a Tesla car that harvests your data and requires you to seek constant upgrades from its parent company. This wave of algorithmic surveillance capitalism is a particularly virulent new form of corporate capitalism (see The War on Informality), but regardless of the form, the act of handing over money in an act of consumption completes the first half of the corporate circuit. Now that money can ripple back to Hollow Shell for the second half.

Completing the Circuit

The income from selling stuff now gets split into different cuts for different parties. Managers get bonuses, creditors get interest, and governments get tax (well, assuming the company hasn’t done large-scale tax avoidance). This leaves the residual as net profit. The managers then get to decide if that will be paid out as dividends to shareholders, or reinvested into further operations. This is the basic corporate capitalist circuit in completion.

Mediating the relationships: Expansion Packs

Each relationship between the different players above carries its own tensions and dynamics. We can explore those by adding Lego Corporate Capitalism expansion packs, which introduce various institutions to mediate those relationships. Here’s a rough sketch of the expanded corporate universe.

The Board Edition: the board mediates relationships between shareholders and managers, which is an element of corporate governance. For example, the board might vote to grant managers stock options, so that the latter think like shareholders

The Union Edition: Unions try to mediate relationships between workers and managers (and, by extension, shareholders). Without it, workers have little individual power to fight for a better position for themselves

The Regulator Edition: The regulator expansion pack gives tools to control various aspects of the relationships. Financial regulations set rules about relationships between companies and financial markets (e.g. is management allowed to do insider trading of the company’s shares?) Labour regulations focus on relationships between companies and workers (e.g. is the company allowed to refuse workers paid sick leave?). Consumer regulations deal with relationships between the corporate entity and customers (e.g. should food products have to include a list of ingredients?)

Lego Corporate Capitalism Fractal

Lego has various lines, like Technic, that cater to older kids and teenagers who get bored with the simpler stuff. In future we can add a Lego Corporate Capitalism Fractal line to expand the complexity of the picture.

The basic Lego Corporate Capitalism line builds itself around a single Hollow Shell, but a true corporation is actually a giant federation of hollows shells. For example, I mentioned earlier that BP is a collection of over 67,000 people, but what we call ‘BP’ is also a collection of over 1000 subsidiary companies, each of which is technically a separate entity, but all of which are linked together under a single parent company. The image above comes out of some work that I did in 2014, in which I mapped BP’s corporate structure. The mothership legal entity is called BP PLC, but it then owns subsidiaries that own subsidiaries that own subsidiaries, and so on. In fact, the subsidiary structure is twelve layers deep.

This is one area where my picture above starts to get fractal, because the parent company, which has its own shareholders, will in turn insert itself in as the shareholder for its first layer of subsidiaries, which become shareholders of the next layer. A true corporation contains thousands of micro versions of the corporate structure within itself. Subsidiaries can take on the role of creditor to other subsidiaries (especially when the company management is trying to do various tax shenanigans), or supplier: indeed, these subsidiaries are made to ‘do business’ with each other, while being directed from the central planning headquarters. What we call BP, then, is actually an entire sub-economy in itself, with hundreds of thousands of people stretched out across countries, merging into other corporate sub-economies.

The connections

We can deepen this complexity even further when we notice that our economy is a huge interdependent structure where each person can take on multiple different positions at once. As you walk into your office you might be a worker, but when you go to the store you’re a consumer. Perhaps your company does work for other companies, in which case you contribute to a supplier. You might also have a pension, which is managed by a fund manager that’s investing in the shares of the very company you work for. Maybe you’re hoping that these small shareholdings will someday enable you to escape from working at that very company.

Learning to see these connections is crucial for understanding economic politics. For example, companies often brag about how they’re reducing prices for the consumer, but that often entails them driving down wages for the worker. Those workers, in turn, can be placated by giving them small slices of the action from the stockmarket, so they have a small stake in exploiting themselves.

The financial sector too has its own fractal universe. I presented it this time as plugging itself in to capitalize the corporate entity, but it can plug itself in all over the picture. It can finance the suppliers with trade finance, finance the consumers who go into debt to buy the products, and even finance the people training to be workers for the financed corporation. It will also finance financiers, who may be doing the same.

The fractal patterns go both smaller and larger. Zoom out, and the picture of a single corporation becomes a picture of entire industries that lock into other industries, and entire classes of people locked into forms of tense and unstable symbiosis within a giant web of financial contracts. And, this entire structure can only be woven together because of the money system.

That, of course, is the glaring missing piece from the picture above. I abstracted money away from the picture this time for simplicity, but the true Fractal series that we all need to grapple with in future is how corporate capitalism and monetary systems are part of the same continuum, with no beginning or end.

Fantastic. I'd love to teach this. Actually, I do teach this -- I co-direct the University at Buffalo NYC Program in Finance & Law -- but I don't have Legos! Please get this built. Happy to discuss further, quibbles, add ons (though fractal is wonderful) . . . bravo.

Such a lego set would be very instructive, particularly if paired with a Biosphere set on the same lines. The complexity of the relationships and the essentially parallel interactions would lend themselves to a generic production line but - and this is the kicker - with vastly different results. The game could be further enhanced with betting on what leads to the different results. My money, such as it is, is on humans inability to manage complexity in a system that absolves them of responsibility.