I used time-travel to uncover three secret messages hidden in a popular Bitcoin meme

And in the process revealed one deep truth underneath it all

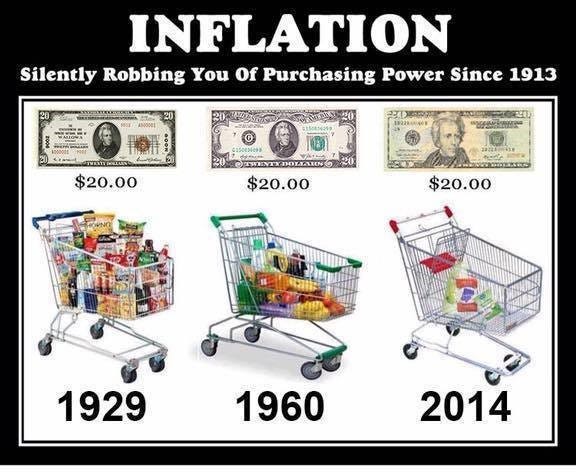

I’m going to tell you a story about time-travel, but first I’d like to ask you to look at this meme closely. Don’t analyse it too much. How does it makes you feel?

This meme is designed to exploit a number of weaknesses in our understanding of money, and to play on our fears. I’m going to show you how it does it, and why.

Now it’s story time.

The Time-Traveller

Imagine you’re a worker in 1929. You’ve spent a week labouring, and get paid a wage of $20. You’re a low-paid worker - others in the car factories are making up to $30 a week.

Every Friday evening, after you clock off work, you walk tiredly to the store and exchange it for a basket of goods to feed yourself for the next week. You get porridge, cigarettes, bread and so on.

You don’t spend it all, because you’re also slowly saving up for a piece of high-tech equipment. You see it in the window of an upmarket store each day, and it costs an outrageous $150! It’s taken you almost a year to save up, but you’re edging your way towards having enough. Here it is, a beautiful Victor Gramaphone.

One Friday you have to work later than normal. You clock off and get paid your $20 for the week. Exhausted, you slowly trudge your way through empty streets towards the last open night store. Suddenly you feel static electricity crackling in the air around you. A strange light appears in sky above, and a weird whooshing sound comes screaming out of the night. A terrifying time portal from the future opens up, and - before you know it - sucks you in!

You find yourself projected through a harrowing vortex that feels like this. It hurls you forward 91 years into the future and dumps you outside a mall in 2020, still holding your $20.

You raise yourself to your knees and find yourself in a parking lot. Some stoned teenagers are staring at you whilst playing strange music out of boxes. They hold rectangular gadgets with shining lights that they tap with their fingers. Impossibly advanced automobiles race down a highway to your side. You’re in a frightening landscape of steel, glass and concrete.

You scream and run to hide in the shadows under an enormous billboard of someone called Rihanna. You slowly calm down, and discover you’re absolutely famished - the time-travel really depleted your energy. You smell a delicious aroma wafting from a hipster food van selling burgers outside the mall. You cautiously approach it, but scream again: to your dismay you see that a single gourmet burger COSTS $20!

In the world you just came from, you laboured for an ENTIRE WEEK for that $20, but in this new world you’re now supposed to hand it over to someone who spends no more than 10 minutes frying up a burger?!

A few hours later some cops find you wondering the streets in a daze, and they take you to a hostel for the homeless. This becomes your temporary home while you try adjust to your new society. You begin to learn things about this strange world. For example, it dawns on you that other people seem happy to buy the burgers from that van because they seem to get paid much higher weekly wages than you used to, so in relative terms the burger seems less expensive to them than it does to you.

You also begin to notice that they have a lot more stuff than you had in 1920. Even the janitor in your shelter has one of those magic gadgets with a screen.

The shelter organises for you to get some part-time work as a removals worker. The company will pay you $75 a day. Wow! That’s more than three times what you used to get paid in a week. One day, you’re passing an antiques dealer, and you see your beloved gramaphone! Miraculously, it still costs $150, although it does look a little more beaten up than it used to. Still, you scream with excitement. Oh sweet lord, I can get the gramaphone for just TWO DAYS OF WORK! You run into the shop looking like this…

What does this story tell us about the Bitcoin meme?

Look back at the supermarket trolley meme we started with. It tells the exact same story as I just did, but with a different spin.

The top half of the meme tells a story of a person in 1929 with 20 dollars in their pocket, who is suddenly projected forward into 2014 to discover that the 20 dollars they earned from their’s week’s labour only buys them a tiny amount of stuff.

Weird. How did this person end up in 2014 with only 20 dollars? Time travel? Cryogenic freezing? Really good genes but really crap pension?

A financial advisor in 1929 probably should have told this person to invest their money into financial instruments like shares, so that when they froze themselves for 85 years they could have taken a percentage cut of the economic activities of the people who kept working.

The bottom half of the meme, though, tells another story.

In this story, someone in 2012 apparently earns something called 1BTC, but then finds that the store will only give them a small amount of stuff for that. Two years later, however, their wage hasn’t changed, but the store will now sell them an overloaded trolley for exactly the same price. Miraculous. How did that happen? Where did all that extra stuff come from? Isn’t it amazing that a week’s labour in 2012 earns you the right to command many months worth of labour from other people in 2014? I mean, somebody made that stuff in the trolley right?

Imagine if all our salaries just kept multiplying in power in this amount of time. We’d all be getting so much more stuff from… well… all those people who are making that stuff.

Wait a moment. Something is suspicious here…

This meme is designed to make you feel angry about your loss of purchasing power as a small saver, and it does this by decontextualising the act of spending money from the act of earning it. When you place its images into a more holistic context, and recontextualise them, this meme not only falls apart, but reveals three secret messages hidden within its structure. They are like an payload waiting to be delivered into your consciousness by a Trojan Horse. Here are the three messages.

Secret Message 1: Creditors are your friends

If you walk into a supermarket, you are easily able to make a distinction between the diverse range of goods you see on the shelves, and the money you use to buy them. You can in fact abstract from that to imagine an entire society: at any one point, there is a diverse pool of goods and services in a society, and a pool of money being passed around to claim those goods.

Back in 1920, your $20 claims a certain percentage of those goods. In 2020, though, it doesn’t claim the same percentage.

This is not actually that surprising, because there were 100 years between 1920 and 2020, and in that time vast changes occurred within the economic system. These changes include such things as:

Billions more people entering the global economy

Massive expansion of economic production

Massive changes in technology

To visualise this, imagine the economic system as an interconnected network of people producing things, but expanding outwards, like this:

The world of 1920 is like the opening phase of this image, when there are far fewer people, far fewer connections, and far fewer things. The world of 2020, on the other hand, is a far denser and bigger network. This is by no means always positive - for example, there are very serious environmental consequences to an expanding economy.

Nevertheless, for the purposes of our meme analysis, the first question you want to ask yourself is this: Does the average person in 1920 have more stuff than a person in 2020? I mean, that’s what the meme is trying to imply. They show your trolley getting emptier and emptier. You’re losing something, right?

Do a quick reality check on this one at the supermarket. Imagine a 1920s general store. Compare it to a modern Wallmart on Black Friday. Whose getting more stuff?

The second question you need to ask is this. In what world would you expect a money unit to remain stable for 100 years?

I’ll tell you. A static, frozen world. Let me show you an example of such a world.

You can play Monopoly in 1960, and then store it away for 60 years and discover that nothing changes. This is because the game designers have simply assumed away all the actual dynamism of an organic human economy and created a static rule set in which the money units will always claim the same amount of stuff no matter what (see my in-depth analysis of Monopoly Money if you wish to explore this).

The Monopoly world is frozen in time (like a paused version of the network animation above). There are no students entering into the labour force trying to find new jobs. There’s no population growth. There’s no life. There’s no fluctuating pricing. There is, in fact, no actual capitalist system with a growth imperative trying to expand the economic network to ever greater scales. It’s almost… well… a steady-state centrally-planned economy with no people.

Regardless of how you describe it, you can be sure that if you earn $20 in the Monopoly world, and then come back decades later, that $20 will still do exactly the same thing.

Organic economies do not work like the Monopoly world. Imagine a bear hibernating for 85 years and then waking up into an expanded population of younger bears before charging around and angrily demanding the exact same percentage of the berry-patches he was used to when he went to sleep decades ago. Oh the injustice of his loss of power. These lazy young bears should have been keeping his patches intact!

The equivalent behaviour for our time-traveller would be for him to rough up the stoned teenagers in the parking lot, demanding that they hand him more purchasing power in the form of their wallets, so that he can claim a burger without losing his own purchasing power. Give me my rightful share of this society’s goods!

So, yes, it is true that 1920 credits do not do what they used to do, but it’s also true that in the mean time new generations of young people have massively expanded the economy, which is one of the reasons why the 1920 credits have been rendered comparitively less powerful as the economic network has expanded.

Ancient hunter gatherers intuitively understood that if they failed to keep hunting or gathering they’d fail to survive, and that principle - that humans survive on short-term production cycles - remains to this day. This is one reason why there’s something of a ‘use it or lose it’ element to monetary units, which mediate access to an organic human economy.

Don’t misinterpret me. I’m not saying that there are not abuses of the monetary system by the powers that be, but notice how inorganic the message of the meme is, presenting a social system which is supposed to leap a gap of 100 years with no change.

My family is from Zimbabwe, so I know that inflation in excess can be a very bad thing, but I’d like to ask you what the mirror-image of hyperinflation is. Well, it’s a world in which money units get ever more powerful, but have you ever wondered what that world is? Any ideology that tells you that it is naturally good that money gets more powerful over time is fact an ideology of people who wish to cling onto power despite not working. What are these people called? They’re called creditors, those who stand to benefit from renting out access to a limited means of exchange to newcomers who are trying to enter the fray.

Even conservative economists like Milton Friedman realised inflation went hand in hand with a growing economy. This is a complex topic to convey in a single post, and there are many ambiguities to it, but - in crude terms - if the money supply is held taut in the midst of an expanding economy it can act like a form of strangulation: your production is supposed to expand whilst the money stays taut, which means the creditors become very powerful as those without money demand it, in order to ‘breathe’.

This is a highly simplified account, but it might offer some insight into why a trolley might ‘fill up’ with unearned goods as those holding onto constrained money can claim more from the young people who are producing the new stuff.

Secret Message 2: Capitalists don’t screw you. Money does.

Let’s look at the top half of the meme again. It is decontextualised, so there’s no explanation for how the person gets their $20, but it presents those dollars somewhat like a disintegrating commodity, like a grain rotting away over time.

By presenting this situation out of context, the meme is designed to conjure the commodity imagination of money, but to apply it to a form of money that simply isn’t a commodity.

The commodity imagination is not a theory. It’s an orientation, mindset, or way of approaching money, in which it’s imagined that money units are - or should be - some kind of ‘substance’ that ‘carries value’. Many (if not most) people subconsciously use this orientation, and it often leaves them susceptible to believing that modern money is somehow ‘not real’, because it is not a true commodity. This also leaves them susceptible to believing that modern money might be a kind of unnatural abomination which is rotting away because of the deceit that lies behind it.

I write a lot about the psychology of this imagination in other places, but for our current purposes the main question should be to ask what is happening to this ‘rotting’ money. In the case of grain, it literally decomposes and turns to dust, but the meme isn’t trying to imply that the physical material of banknotes is disintegrating. It’s trying to argue that the ‘value’ is escaping from the dollar, but where is it escaping to? Is it like a gas leaking out of the atmosphere into space?

No. Monetary systems are closed systems. The internal supply of tokens can certainly fluctuate, but every act of ‘paying’ in one part of the system is also an act of ‘being paid’ in another. One person’s spending is another’s income.

Let’s turn back to the supermarket example shown in the meme. How does the money turn into goods? Well, you hand it to the supermarket cashier, who puts it in the till, from where it will eventually end up in the bank account of her bosses, who will pay her a small slice of that as wages for being a supermarket cashier. Those bosses will also use some of it to pay the suppliers of the actual goods. The remainder is called profit.

In other words, your spending in the supermarket gets split into slices that end up as the income of a whole range of different people and companies, but somewhere else in the system other people are spending, and that ends up as your income.

Our 1929 Time-Traveller was getting his income in the form of wages, probably from some company that was selling stuff that he was employed to help make. He would get paid and then go to a store to buy stuff that other people were employed to make. Now he gets ported into 2020, but let’s now imagine that, in a state of ignorance about his new society, he tells his new bosses that he’ll take $20 a week to work for them. The bosses look at each other, and say ‘suuuure thing buddy’.

Now he gets paid his weekly wage, goes to the store, and hands it over to a cashier for a meagre amount of goods. A tiny slice of his $20 ends up being redirected from the supermarket owners to pay the cashiers, who are getting paid $400 a week.

What’s happening here? Well, everyone else’s wages have increased while his have stayed static. This means only one thing. He’s being screwed by his bosses, who are paying him an outrageously low wage whilst pocketing the massive profits from selling the things that accrue from his labour. They’re laughing hilariously at how little he expects. Indeed, they’re going to take those profits, and stock up on five whole trolleys worth of single-malt whisky and luxury goods.

If you find yourself in this situation, feel free to go picket outside the Federal Reserve to demand an increase in the purchasing power of your $20, but I’d personally suggest that you consider joining a union, because all your fellow workers are getting paid way more than you are. In other words, it’s possible that you’re not so much being screwed by the monetary system, as you are being shafted by your bosses.

Secret Message 3: Our liberation comes from debt-bondage

So, let’s recap. Not only is this meme designed to naturalise the interests of creditors, but it’s also designed to blame the monetary system for low wages given out by wealthy CEOs. So much for standing up for the little guy.

But it gets even worse.

Let’s turn to the bottom half, which tells that story about a person in 2012 who finds themselves getting all that new stuff in 2014, bursting out of their trolley like a consumer cornucopia. Their money is powerful right?

The thing about money is that it’s actually nothing without people. It’s not like the power resides in the money. It resides in the economic network which is accessed through money. It’s not the money that’s getting you that stuff. It’s people that are getting you that stuff.

For example, you could find yourself deserted on a distant island with a billion units of money, and still starve to death, because no amount of throwing money at the forest will make anything emerge. Those units are meaningless unless they are locked within a labour network, and this applies to any form of money, regardless of who issues it or what its characteristics are.

So then, where are those goods in the trolley cornucopia coming from? Well, other people of course. But how is it that these people are falling over themselves to gush out all these goods for the person pushing the trolley around, seeing as though two years ago that person was not prepared to do the same for them?

Perhaps there’s another side to this story. Let’s imagine, for example, that rather than being a person who earned 1BTC in 2012, the person was a broke, unemployed worker. In an act of defiance of their situation, they resolved to become a small-time entrepreneur. To start their ceramics enterprise, they took on a 20 BTC loan from a creditor. They use some slivers of it to buy supermarket goods, but the rest gets poured into buying the materials to start their business. The interest rate seems ok - they believe that they’ll be able to make enough stuff to sell, which can be used to pay off this loan in a few years time.

But wait. There’s a problem. The money units used to price everything keep getting ever more powerful relative to the things they are used to price. This means the person has to sell a lot more pottery than expected in order to keep up with loan repayments. Oh crap! The money has quadrupled in power in one year, which means the person will have to sell four times more actual goods than expected to get the same amount to repay the loan. They’re suddenly extremely stressed. How on earth can I make that much! They’re racing to desperately produce enough to try eke out the income to repay their debt.

Someone else on the other side is seeing that as their trolley getting ever more full. Ah, this magical money is just miraculously bringing forth more goods into my trolley like mana from heaven! Amazing, let me also buy some fine ceramics.

That mana comes from debt traps, and that isn’t heaven by any stretch of the imagination.

The One Deep Truth underneath it all

I’ve showed you the three secret messages that can be pulled out of this meme through time-travel, but let me now reveal the one deep truth that beneath all of them. None of these apply to Bitcoin in the slightest.

But why?

Well, it’s simple. Bitcoin is a sophisticated - even elegant - system for moving digital objects around in a decentralised manner, but it is not a monetary system. Those objects are priced on a market, like any other object, but they use moneylike branding and slogans to compete for attention against other objects, which might otherwise be bought instead of them.

Memes like the one above are part of the marketing pitch, and have three objectives. The first is to do some conservative monetary scaremongering, to leave you believing that you desire deflationary money. The second is to then present to you a non-monetary object which superficially looks like this ‘deflationary money’ you seek. The third is to then sell you this object for… well…. actual money.

Think of Bitcoin tokens as being like ornate digital collectibles, with elegant monetary branding carved into them. They are available for sale in all good online stores that sell digital collectibles, and the darkest of the secrets in the meme is this: the Bitcoin collectibles in the bottom half are not competing against the dollar in the top half. They are competing against the goods in the supermarket trolley.

The objective of the meme in 2021, is to get you to take your 2021 dollars and spend it on Bitcoin (sold by one of those dealers operating out of the digital collectibles market), rather than spending it on trolleys full of actual consumable goods. This will allow a Bitcoin dealer to take possession of your 2021 dollars, and then walk outside to a supermarket and full up a trolley with bourbon and pistachio nuts.

This is easily confirmed by perhaps the most obvious flaw in the meme. No supermarkets accepts Bitcoin, and no labourer producing the goods in the trolley gets paid in Bitcoin. It is - in other words - something you can choose to ‘put in your trolley’, rather than something you use to buy the trolley goods with.

The meme is so successful because it plays on the ambiguity of the collectible, which uses its ‘moneylike’ branding to pass itself off as a competitor to money rather than a competitor to goods. If you want to read further on this, check out my piece for Coindesk, called How to Win a Bitcoin Street Fight.

This branding has been very successful, and now the object is appreciating in price, as people try to buy them from the dealers. In a transnational economy with billions of people, there indeed are hundreds of millions who might be prepared to buy such an object, especially in anxious times, and its market price could rise a lot as the dealers who hold it sell small slivers to those trying to buy it.

The dealers use this price rise to feed into the existing marketing they started with. They say things like ‘Bitcoin is rising against the dollar’, when what’s actually happening is that Bitcoin’s price relative to other goods and services is rising, as it defeats other objects in the trolley in the race to be bought.

The dealers might say ‘Bitcoin is increasing in purchasing power’, but Bitcoin is not used to purchase things. It is, rather, something that is purchased.

Imagine going into a store, buying an expensive item, and then returning a few days later to return it. The store has two options. It can give you your money back. Or it can tell you that you can swap the returned item for goods of an equivalent price. In this latter situation, is this returning good now 'money’? No. It’s a money-priced good that can either be exchanged for money, or swapped for other money-priced goods (this is called ‘countertrade’).

Similarly, you can buy Bitcoin in a market for digital collectibles, and you can return to that market to resell it for money. Alternatively, you can swap it - or countertrade it - for another money-priced good. Those are the two options, and neither of them entail Bitcoin being a monetary system. It remains, as ever, a movable digital object with moneylike branding.

The good news is that this means the ‘cornucopia’ of stuff overflowing out of the supermarket trolley in the meme is actually not being extracted through debt slaves. Rather, it’s happening through the bog-standard process of selling something for more money than you bought it for, and then using that money to buy more stuff. This is probably somewhat less destructive than a highly constrictive deflationary currency.

The bad news is that in the process of trying to pump this object with this monetary branding, the dealers are telling millions of people deeply conservative stories about the monetary system, and packaging it up as some kind of exciting radicalism. In fact, if anything, they’re just helping to empower the standard conservatives within the normal fiat monetary system, who benefit from the ideological messages within the marketing used to sell the objects.

Upon reading this, those dealers will probably deny this. They will probably argue that I’m a stooge for the fiat money system and the banks and the Federal Reserve. But I’m not the one trying to sell you Bitcoin collectibles for dollars, am I?

You are mostly arguing against Strawman here.

Nobody believes Bitcoin is a workable currency to denominate all value as of today. But people speculate that it will be one day. If it succeeds, it will be slightly deflationary, but I don't think this is a hindrance. It does shift the incentives from being a debtor to being a creditor slightly, though. Is this a bad thing?

Also, was the meme really created by exchanges or sellers who want to get a hand on your Dollars? Or is it rather an expression of excitement of some guy who got rich on buying early? I don't think you should try to debunk Bitcoin based on some meme.

Apart from that, Bitcoin needs more serious critics like you!

Very good analysis, I fuly agree. Bitcoin is not well suited to function as "money" and in that respect, Satoshi's design proved too simplistic as The Economist observed already back in 2011 (https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2011/06/16/bits-and-bob). However I am curios as to what is your take on more recent, less well-known and understood blockchain-based designs. I wrote a post in my blog, I'd be honored if you found time to read it: https://steemit.com/hive-155234/@sorin.cristescu/crypto-communities-need-to-provide-value-to-the-world