Paying subscribers can listen to me reading this article here

Every day, a tsunami of anger and despair rises up in millions of people who’re being screwed by some form of corporate shittery.

Maybe it’s a health insurance claim that’s been arbitrarily refused, or a rental contract that’s increased without explanation. Perhaps it’s a crucial account that’s randomly been shut down by some automated bot.

The negative emotions build up in people’s bodies like a giant charge. If these feelings can’t be released, they’ll have to be suppressed, but suppressing them is like pushing a dark spirit down into the depths. The emotions want to come out, but where can they be discharged?

The most obvious target is customer service staff. The angry customer picks up the phone, or bashes away on the help chat, or storms up to the counter of a branch. The job of the employees behind those counters is to get punched by that dark spirit - the rage, confusion, or desolate sense of injustice welling up in the customer - and to absorb it, so that big bosses, far from the frontlines, can go about their day without feeling the consequences of their decisions.

Those frontline employees occupy a realm I call Bufferland. It’s called Bufferland because its purpose is to act as a buffer, insulating the elites that sit within the high citadels of capitalism.

Bufferland is distributed all over the earth. It takes the form of call centres, shop frontages, cashier points, info desks, online forms and any other interface that stands between you and the management layer of our global economy.

Bufferland is often a warzone. For example, I’m in Bufferland right now, in London’s Gatwick airport at a boarding gate. I’m facing an easyJet employee behind the desk. He seems to hate me, and I’m being pushed towards hating him too. I can see the strain on his face that comes with being cannon-fodder for distant bosses, sent out to fuck over the customers.

I’m going to tell you what this showdown is about, but let’s first take a step back to explore the connection between this man and the big boss that he’s protecting.

The Citadel

Big bosses reside in a citadel, far from customers, and far from service staff.

Like Bufferland, the Citadel isn’t a single place, but rather a distributed collection of skyscrapers, boardrooms, elite holiday homes, convention centres, five star hotels, business class lounges, and mobile phone contact lists between powerful people.

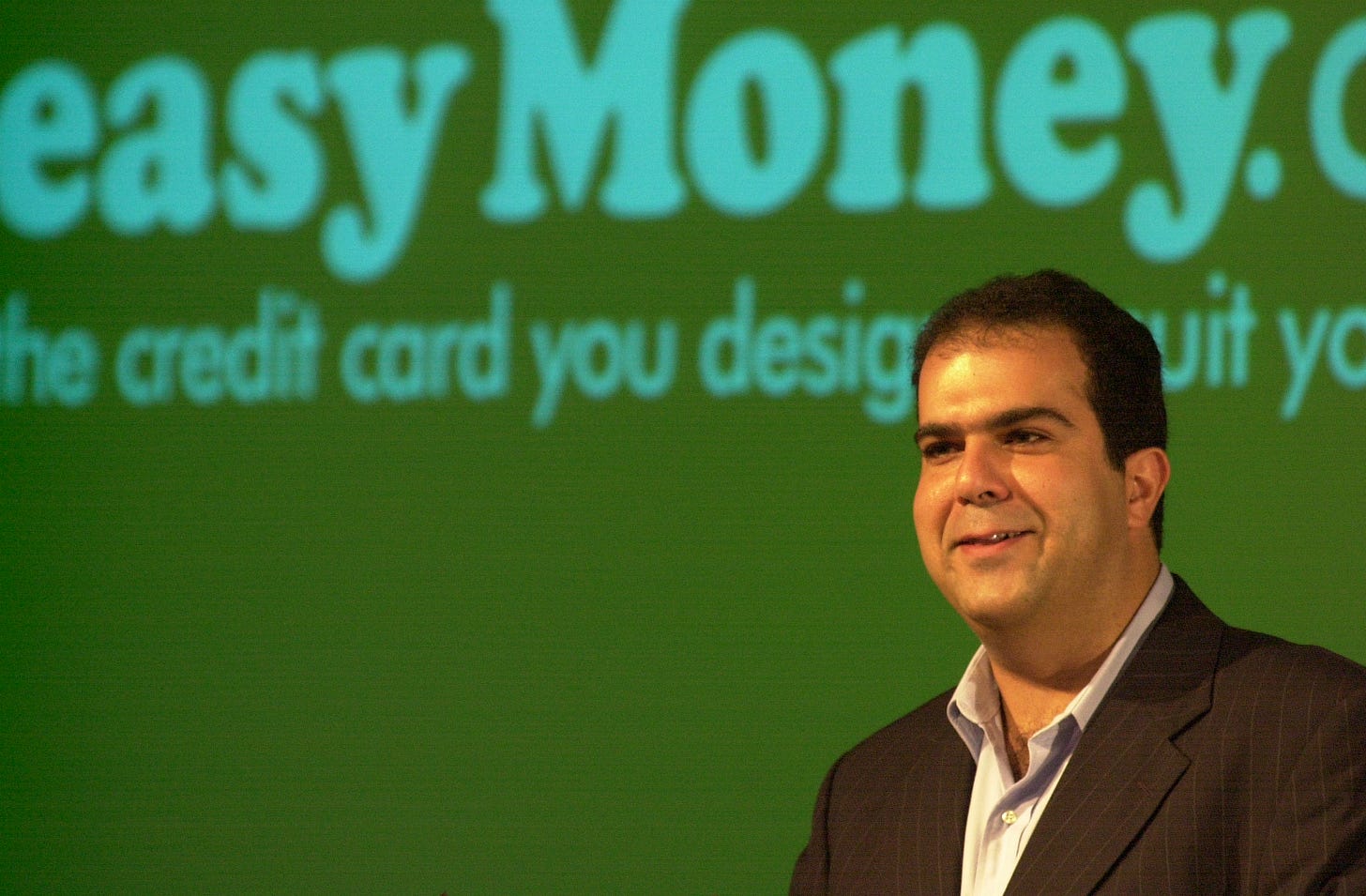

For our purposes, let’s focus in on Sir Stelios Haji-Ioannou, who is the biggest boss being served by our humble easyJet employee. Sir Stelios is easyJet’s founder. He doesn’t actually run the corporation day-to-day any more, but he’s the largest shareholder, owning 15% of the company. That means 15% of all profits accrue to him and his family.

Stelios is a classic capitalist, born into a mega-rich Greek shipping family. He worked for his dad until age 25, after which his father gave him £30 million to set up his own shipping company. By age 28 he used the profits of that to found easyJet.

Capitalism is called capitalism because it involves capitalising on previous power to get more, and Stelios is good at that.

When I call Stelios a capitalist, I’m simply describing his position in our economic structure. I’m not making a moral judgement on his character. I’m not saying he doesn’t feel emotions, or bleed like anyone else. If you watch him in interviews, he can be charming and well-spoken, and he has a philanthropic streak. I’m sure he’s a delight to have as a dinner guest, and I’m sure he can tell a lot of fascinating stories, about the time he was knighted by the Queen, for example. I’m sure he can be warm-hearted to his friends and family, and I’m sure he probably offers kind words of encouragement to students and so on.

But, in the end, he’s a person in a position of extreme power, and he always has been. That warps his sense of normality.

For example, Stelios talks proudly about how he took ‘outrageous risks’ when founding the company in 1995, but it’s of course much easier to take outrageous risks when you control outrageous amounts of money. In reality, his major risks involved daring to bypass the travel agencies, and daring to sell coffee on flights, and daring to cut deals with smaller airports. These are not insignificant innovations, but it’s not like he faced starvation, destitution or deportation if they didn’t work out.

Nevertheless, through methods like these, easyJet could tout itself as democratising travel. It, like other low-cost airlines, has always imagined itself as a great champion of the working man and woman, who can’t afford the premium airlines that target the upper middle-class.

The catch, however, is that people who want to go on cheap holidays tend to also be people with low wages, and people with low wages tend to be the kind of people who are subordinated under the rich - i.e. under people like Stelios.

We don’t live in a utopia, where cheap travel springs out of the ground fully-formed. No, cheap travel is wrested from the earth and its people by using low-paid labour, dirty fossil fuels, automation, and other cost-cutting tactics that make everything feel kinda shitty. It just so happens that it’s the powerful in our society who - on average - control those very processes.

We live in a tiered economic system, with multiple layers, each with a different living standard. People like Stelios occupy the highest rungs. They own large concentrations of stuff - built by other people - and then get other people to operate that stuff for them so that they can make more money to buy up more stuff.

For example, Stelios didn’t build the aircraft that easyJet owns, and he doesn’t extract the fuels required to fire them up. He doesn’t fly them, or load them with baggage, or do any of the ground-level tasks that make low-cost air travel possible.

Rather, his primary role was to have the money - the capital - to command other people to do those things, and thereby make easyJet a reality.

His secondary contribution was strategy and management. In particular, he set about designing cost-cutting processes to make the aforementioned conglomeration of inputs (workers, aircraft and other assets) relatively cheap, such that the output (budget air travel) could be sold to all the people on the lower rungs of society.

The people on the lower rungs of society, however, tend to also be the people who are weakened by cost-cutting processes on the production side of our economy - this is the squeezed working class - so selling them cost-cut goods on the consumption side is a very dubious means of salvation.

Unfortunately, if you cannot see the circuitry of capitalism, it’s easy to be confused by this. To countless low-wage employees across the world, low-cost products will seem attractive - even ‘liberatory’ - but, when you zoom out, they are the ones cheaply producing the cheap things that are being sold back to them.

One of the most perverse elements of our economic system, then, is that people like Stelios will often be seen as liberation figures, fighting for the weak. In fact, Stelios even sees himself as the ‘Robin Hood of the airline industry’, and a ‘consumer champion’…

But, whenever a company is claiming to ‘democratise’ something, they’re basically saying that they will drive down costs on the production side of the equation to get the consumption side hooked on the resultant cheap thing, after which they will be in a position to extract.

Put bluntly, for Stelios to give the rabble cheap travel, he must squeeze the rabble in the process, and in exchange for his capital and decisions, he gets to own large amounts of shares to accumulate the profits that emerge from that.

With this in mind, let’s return to Gatwick airport, to the queue at the boarding gate.

Skirmish in Bufferland

It sometimes feels like easyJet’s management presents customers with a devil’s bargain: we’ll give you cheap travel if you agree to hand over your dignity and be treated like the crap you are. They don’t say that, of course, but it’s implied in the way we’re pushed through their systems like a herd of cattle, and milked at every possible opportunity.

Getting people to fight each other is a core part of the business model. For example, the company wages psychological warfare on their own customers, getting them to battle one another for overhead bag space in order to push them into paying extra for Speedy Boarding. They then let the cabin staff deal with the fallout of that, as upset customers who board later complain of having no space for their bag.

When the core of your business model involves squeezing both customers and employees, it means that relations between those two camps very quickly get frayed. The stressed employee and the stressed customer are both being played by the senior management, but they often end up facing each other as mortal enemies in different parts of the system.

That’s how I’ve ended up facing this guy at Gatwick airport. Here’s the story.

I was allowed to enter the aircraft in Berlin with a medium-sized travel bag, and fly to London with my friend Julio for some meetings. We came back to the airport last night to check in for our return flight to Berlin. We waited for four hours as the flight was repeatedly delayed. Then it was cancelled, late at night, and we were told that a replacement flight would leave early the next morning. The boarding staff instructed us to download an easyJet app to get a hotel, but it repeatedly failed, flashing up an error notification. So, just before midnight, we trudged into the cheapest Gatwick hotel and had to lay out a couple hundred pounds each for a room. We then had to go onto another online site to put in an expense claim for that, and were told it would be repaid in 28 days, if the claim was accepted.

All of this was annoying, but we were stoical about it. Such is life. These things happen.

This morning we got up and passed through security again, and checked in again, and then waited in a line with all the other bleary-eyed people to finally board.

But then something weird happened. As I got close to the boarding point, I noticed them forcing an elderly woman to pay extra for her bag, despite letting others with bigger bags through without penalty. That was dickish of them.

Then they did it to me too.

So, here I am, facing the man. Rather than the airline saying we are sorry for messing up all your travel plans and making you spend lots of money on hotels and overpriced airport food, he’s trying to tell me that I’ve been arbitrarily selected to pay an extra £50 to enter the massively delayed flight.

Imagine if a small business owner did something like this. Let’s imagine a removal guy with a van. Let’s say I booked him one evening to help me move house, but he keeps delaying, and then finally cancels late at night, telling me that actually he underestimated the time it would take to finish another job, and that he can only turn up the next morning. In a situation like that, he’d be deeply apologetic when he arrived the next day. He wouldn’t start to quibble about me having an extra box, and would probably throw in some freebies.

This is because a small business owner experiences human emotion directly. When dealing with a mass scale corporate operation, however, the act of screwing me is treated by the management as a cost of doing business, and the job of dealing with the rage that emerges from that is outsourced to Bufferland. Let the customer service staff get shouted at, and then direct the angry man to a compensation form, or just ignore him.

Bufferland exists to provide a shallow layer of human care within an otherwise bureaucratic profit machine, but today easyJet is also using it to recoup its losses from yesterday’s cancelled flight. The employee clearly has a quota to fulfil and as he tries to avoid making eye contact with me, I complain about the unequal treatment. They’d let me onto the plane from Berlin to London with this same bag. They’d cost us money by cancelling the flight. They’d let others through with bigger bags. WTF is this?

In the end, the choice I have is this: accept the fact that I’m a sacrifice to the shareholders of easyJet, or be the arsehole who kicks up a fuss and complains about the fact that most others aren’t being punished. It’s like a banal, low-level version of the Hunger Games: be noble and sacrifice yourself for the elites, so that everyone else, including this staff member, can be let off.

So, I suck it up and accept the fate, but I can’t help but make a few existential comments about the random bureaucratic violence of corporate capitalism. This is too much for the employee. He scowls and says ‘I can’t do anything! Speak to the management.’

Economies of Silence

Bufferland does have secret pathways that allow certain people to bypass it. You can ‘speak to the management’ if you have enough power.

For example, I was once invited by some businessmen to Kazakhstan. They wanted me there in three days, but as I stood in a queue to get a visa I was told it would take eleven days at minimum. The businessmen thought otherwise. They made a phone call. The next day I had a visa. It was like Jesus parting the waters to allow me to walk straight through the apparent obstacle. A miracle!

Yes, Bufferland can be breached, but only if you’re part of the inside club. If you’re a person of enough power, you do in fact get to make a phone call to Sir Stelios.

If you’re not, you get to do nothing. What does ‘speaking to the management’ mean in the case of 99.999% of easyJet customers? It means you get to go onto an online portal to write out some complaint in a box and then push send. You get to shout into the digital void. In this system of ‘democratised’ air travel, you get to direct your voice towards a hybrid digital-human layer, that will send it to a place where it’ll never be heard by anyone truly benefiting from the system.

Companies like easyJet drive down prices through so-called ‘economies of scale’, but they also make heavy use of Economies of Silence: the frontline employees act as punching bags for customers, like an emotional shock-absorber, but this also serves as a system of noise-cancellation for management, freeing them from the emotional responses that would come from actually hearing the customers’ voices.

But, all that emotional noise and energy that gets absorbed by the service staff must surely take its toll, seeping into their bodies. As they take the night-bus home from Gatwick airport, the boarding gate official might mindlessly watch YouTube, trying to disassociate from a day of being insulted, glared at, screamed at, and cried at by angry or desperate people.

Sitting on the plane, Julio notes to me that companies like easyJet blend Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World with Orwell and Kafka. We’re drawn in by the cheap goods like a drug, while the systems extract our data and spy on us. When we complain, we’re pushed into an unaccountable bureaucratic maze.

I wonder whether Stelios has himself ever experienced this cocktail. I’m sure he’s done publicity stunts where he lines up with the customers, or inspects the staff, but he’s always going to get five-star treatment. He’s getting 15% of the profits, but there’s no chance in hell that he’s ever going to experience even 0.1% of the emotional consequences that come with his own business model.

In fact, I’m sure he, and his family, use those profits to fly first class on premium airlines to luxury resorts with incredibly high standards of living. At those resorts, he’ll be served by people lower down the chain, who’ll leave work in the evening and head home to places with much lower living standards. As he watches these people cook the omelette behind the hotel breakfast buffet, he might feel a warm sense of pride that they can buy easyJet flights.

But, I also wonder if he, or anyone else in his position, ever gets confronted at elite parties by a waiter, or doorman, or receptionist who’s had a terrible experience with the company. I doubt it, because I guess the offending employee would get fired by their own bosses if they took that outrageous risk and dared to insult a high-profile business baron.

But even if that person did brave that, I’m not sure it would have much affect. I’ve spent time with a lot of corporate elites, and one thing that I know about them is that they’re trained to appear reasonable, and they’re also trained to suppress their own doubts about their own position. They’re very good at telling themselves that they’re good people, giving Britain cheap air travel, or securing America through surveillance software, or pushing forward humanity with humanoid robots.

You see, Bufferland exists inside a person too, in their own head. They can use it to push those nasty emotions away from their inner citadel, and to protect that sense that they’re doing god’s work as they kneel to get knighted for their service to humanity.

A shout out to rail/coach/ferry travel. I quit flying for environmental reasons a long time back, but these glimpses of budget air travel remind me how good I have it.

I don't know how much your Easyjet flights cost you, but I did London-Berlin for £50 on Flixbus the other week, turned up ten mins before the bus left, had pleasant informal times with the cheerful staff/drivers, saw dolphins while chilling in the comfortable ferry bar and really enjoyed the journey!

I'm not sure where we non-flyers sit in the hierarchy of capitalism but, for whatever reason, thus far they seem to have overlooked to bring in all the surveillance and enshittification for us.

On this occasion, it even sounds as though I got there faster too, though you did get to sleep in a bed! :)

I do enjoy your writing Brett. I like your term Bufferland. Many buffers contribute to the pain of both employees and consumers. It is the shareholder-stakeholder disconnect—the distance between shareholder incentives and customer experience. There is the strip and flip or private equity buyout, where the firm keeps the owner to run it in the short term, squeezes out quick profits through cuts and price hikes, and then sells it off. Maybe we need consumer unions or public campaigns to highlight and boycott the products. What about a conscious consumer private equity fund? Hey, one can dream:)