Zen and the Art of CBDC Analysis (Part 2)

Five more tips for tunnelling through the CBDC hype-cycle

Part 1 can be found here. Paying subscribers can find the audio version here.

Every group has its trends and cultural expectations that spread mimetically and get enforced socially. If I put on country music rather than techno at a Berlin hipster party, I’ll be shunned. If I defend physical cash at a tech conference, wear a Karl Marx shirt at a Bitcoin meetup, or hand out Google swag at a socialist convention, everyone will avoid me like a plague.

When it comes to mainstream innovation scenes, however, there’s an added element. Not only do these scenes have trends and cultural expectations that you’re expected to follow, but those trends are pushed by systemic forces that nobody’s truly in control of. Capitalism is a headless beast that blindly crawls towards the next new thing, and much of the so-called ‘innovation’ within it is just inertia, the process by which we just drift in a particular direction unless stopped. Furthermore, much of that innovation inertia is just automation, which is the most unimaginative form of innovation, and also the most popular with corporations, because it helps them to accelerate everything, fire their employees and pursue their never-ending quest to turn the entire planet into a giant robotic mall.

It really isn’t particularly innovative to go along with this inertia, but we have a whole class of innovation pundits and futurists who specialise in dancing around it like bards, claiming that this drift represents the will of the human spirit and our bountiful creativity. There’s something almost ritualistic about the ‘hype cycles’ that accompany this. People - feeling powerless to control the drift - choose to imagine that every new technology is some kind of revolutionary uprising that will ‘change everything’. In reality, most of our technologies do the same thing they always do - speed up our lives to make us produce and consume more (see Tech doesn’t make our lives easier. It makes them faster).

In my jaded moments, I call this phenomenon Idiotic Innovation Inertia. It’s ‘idiotic’, in the first instance, because so much of the hype gets directed towards stuff that’s incredibly predictable. Being excited about automation under capitalism is like being excited that a stone gets pulled down under gravity: fine, if you glue yourself to the ceiling, you can choose to believe that the stone is launching upwards into the unknown, but in reality most automation is just pulled into being by the gravitational force of our economic vortex. Right now, there are countless startup teams around the globe contributing into that: they’ve noticed that some aspect of life isn’t yet automated, so will secure venture capital funding to change that, and at some point they’ll get on stage at one of those tech conferences to tell a heart-warming story about how they ‘solved’ some problem through automation that the vast of people didn’t realise was a problem until now.

Sometimes, though, our system also generates random 'idiotic’ perturbations - let’s call them side currents - that briefly ripple into a wave of hype before predictably dying out. NFTs, for example, propagated mimetically through the human population, before the current died off and everyone returned back to the main automation trend. Now everyone who hyped NFTs is hyping that darling of automation - AI. In fact, every blockchain conference in the world right now has pivoted to ‘blockchain meets AI’ to appear relevant.

I’m noting all of this, because anyone who finds themselves in any kind of elite tech or innovation scene is expected to parrot the current suite of generic talking points about the current suite of buzzwords, and this applies to politicians too. One of those buzzwords right now is CBDC - central bank digital currency - which entered the hype cycle in the last couple years. It’s impossible to truly understand the debates around it unless we recognise the huge amount of Idiotic Innovation Inertia that conditions them.

Tunnelling through the CBDC hype cycle

The hype cycle is a methodology from Gartner, which tracks the stages of excitement around a technology. Its peak looks like the top of a hill, but to think clearly you need to tunnel directly through it.

In Part 1 of Zen and the Art of CBDC Analysis, I offered five meditations to help prepare us for that. Firstly, to calm our ideological horses, I explored the difference between libertarian, socialist, anarchist, and centrist takes on CBDC, mapping out how each group is likely to think about it. Secondly, I noted that CBDC already exists under a different name - central bank reserves - and pointed out that the debate is really about whether or not the public should be given access to that existing form of digital money, which has been available to the banking sector for decades. Thirdly, I noted that early proponents of this were actually monetary reformers who wanted to challenge the power of the banking sector: they believed that giving the public access to digital reserves would provide us with an alternative to the existing system of bank-controlled ‘digital casino chips’ that we currently use as digital money. Fourthly, I noted that central banks are not radical monetary reformers, and have no intention of disrupting the banks. Furthermore - contrary to some accounts - they are not considering CBDC out of a concern for being ‘outcompeted’ by the private sector payments players that they underpin and regulate.

So what’s the CBDC debate all about then? Well, I concluded Part 1 by noting that the CBDC discussion in on the table primarily because of the pressure on the physical cash system. Cash is a massive un-automated part of the monetary system, and it’s currently standing in the way of systemic acceleration and automation. As I noted in my recent Aeon essay, ‘it operates at human scale and speed within a system that increasingly demands inhuman scale and speed’. This means there’s a systemic drive to get rid of it, but doing so creates a shed-tonne of systemic instability, because all those ‘cashless’ digital casino chips are in fact psychologically and legally tethered to cash. This causes a classic ‘contradiction of capitalism’: our system wants to get rid of something that underpins it, like trying to shoot of its foot to run faster.

This means central bankers are sensing a systemic pressure, and the emergent contradiction is causing their brains to fret. The predictable thought that forms in their minds is to calm this issue by releasing some kind of ‘digital cash’ that jells with transnational automation while still offering an ‘anchoring’ form of state money. In reality, however, this just means allowing the public access to the pre-existing digital central bank money that banks use between themselves. This in turn predictably leads to resistance from the banking sector, because giving the public access to state ‘digital cash’ threatens the sector’s stranglehold over retail digital payments. This then predictably leads the central banks towards watering down their CBDC proposals to protect the banking sector.

So, the reality is this: current debates about CBDC are on your radar because of the unstable storms caused by the gods of capital, but we’re not supposed to talk about that, so all the innovation bards dance around the topic, reverse-engineering a back-story about what ‘problem’ this is supposedly solving. So, in the spirit of bypassing these people and the hype cycle they serve, I’d like to offer five reflections.

Reflection 1) Idiotic Innovation Inertia creates the ‘official’ justifications for CBDC

Since publishing Part 1 of this piece earlier this year, I’ve been pulled into many discussions with politicians, technologists, and central bankers about the topic of CBDC. What’s striking is just how few of them actually seem to understand why the discussion is happening. It’s like they all turned up at some proverbial grand forum, having been told to be there, but nobody can recall who called the meeting or why they’ve gathered.

The vacuum in understanding emerges from the fact that it’s taboo in mainstream circles to think or talk about the contradictions of capitalism. This means you cannot acknowledge that the CBDC discussion emerges from problems created by digital acceleration and the ‘war on cash’ that it inspires. This also means that people in the mainstream need to invent a bunch of after-the-fact explanations for why they’re at the discussion. Here’s the official list of options they can trot out:

We’re discussing CBDC because it’s important for financial inclusion: people like Queen Máxima of the Netherlands are convinced that it’s a giant travesty that 20% of the world’s population is ‘unbanked’ and thereby not cuddled tightly enough by the embrace of corporate capitalism. Prior to the CBDC discussion she believed that public sector bodies should assist private sector players like Mastercard to infiltrate into the lives of ‘the unbanked’, so that they too could tap their ApplePay watch at a patisserie in Amsterdam. Now, she and others have become convinced that public sector CBDC could fast-track this absorption (which she would call inclusion), leading people into the arms of corporate capitalism without depending upon fickle private sector payments players (who frankly are not always fussed about absorbing unprofitable poorer people into their systems)

We’re discussing CBDC because it solves problems in cross-border payments: national currencies are ecosystems made up of many different players, but at an international level these composite systems become even more complex, because they have to be tacked together via a mishmash of transnational bridges (like SWIFT, SEPA etc). Under conditions of systemic acceleration and expansion in the global economy, there’s a constant perceived need to find newer ‘frictionless’ forms of global payment, and - in the current moment - some have decided to shoe-horn CBDC into that mission. Perhaps all the fragmented private digital systems could all be glued together better if this new public option was available. Some are now framing this as a mission to create a ‘unified ledger’, a transnational system for streamlining the fragmented conglomeration of national ledgers currently used

We’re discussing CBDC because it’s the Spirit of the Times: Sometimes central bankers will weakly acknowledge the systemic automation drive under capitalism, but will do so by imagining it to be like a popular upwelling driven by the individual choices made by the person in the street. The thought-structure goes like this: X seems to be happening in our society, therefore this must mean that everyone desires X, so we should push X as well. They say generic stuff like “our lives are becoming ever more digital”, which then supposedly lends credence to the idea that the central bank is but a passive player that must ‘keep up’ with this inexorable stream, and do its part to reinforce the very same trend through digital innovations like CBDC

Against this backdrop, we find a whole range of academic pundits who pile-on more exotic suggestions for what the true purpose of CBDC is. This includes:

Technocratic macroeconomists like Willem Buiter, who wishes to accelerate his war on the ELB - the ‘effective lower bound’. This is a piece of economist jargon that refers to the fact that physical cash cannot be subject to negative interest rates (aka. somebody cannot push a button to make a £5 bill disintegrate into a £4.50 bill in your hand). You can, however, do that with digital money, so Buiter now believes that abolishing cash and replacing it with CBDC will give people like him a delicious new macroeconomic tool to push people to spend more (incidentally, this property is not unique to CBDC - you can also do it with money in conventional bank accounts)

Others, like Andy Haldane, push a more ‘populist’ technocratic line. He thinks it’s an outrage that the public does not get paid interest on cash, and uses various mental gymnastics to argue that this represents a regressive shadow ‘tax’ which could be reversed if the public was allowed to hold interest-bearing CBDC. You might notice that this is actually the opposite to Buiter, who would create a CBDC that not only doesn’t pay interest, but actively extracts it from people (aka. cash’s ‘lower bound’ protects you from Buiter while thwarting Haldane)

Those careless officials who don’t have their finger on the pulse of public opinion sometimes express excitement about the potential for ‘programmability’ in CBDC, the ability to place limits and conditions on who can use it, for what, and with whom. Historically this kind of conditionality has been used on welfare recipients, but libertarians are causing a lot of stink about it as a tool for a global elite to control your lives (see my essay in Aeon Magazine on how to analyse right-wing theories around CBDC). The posterchild for this is the Mexican economist Augustin Carstens of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), who likes to talk positively about programmability (albeit he’s equally enthusiastic by the possibility of private sector players using it)

Carstens seem blissfully unaware that not everyone in the world trusts technocracy, but it’s not like there aren’t nascent concerns in mainstream circles about CBDC inertia. It’s a standard business meme to contrast opportunities with risks, and in the official discourse the current list of the latter includes:

‘Disintermediation’: this is by far the biggest official concern. It’s the aforementioned fact that the banking sector doesn’t want the state competing with them by providing an alternative to commercial bank accounts. The term is somewhat dubious, because banks are not ‘intermediaries’ in any true sense of the word - they are active creators of money in our system - but basically they’re telling the central bank, ‘back off from our territory’, or ‘if you come onto our territory, you do so on our terms’

Privacy: all mainstream players pay lip-service to privacy concerns, but they will always set it up as something that needs to weighed against the need for transparency. This issue also cannot be separated from the disintermediation point above: the banking sector already runs a giant ‘cashless’ payments surveillance system, so will perceive it as unfair competition if the state offers a privacy-preserving version of the same thing

Digital exclusion and literacy: it’s standard practice in mainstream circles to forcefully push digital systems while expressing concern for the fact that not everyone can use or understand them properly. This normally creates demand for a class of inclusion professionals whose job it is to rectify that

Resilience: there’s increasing concern that digital systems in general are subject to hacking, resource constraints, geopolitical cyber-attacks and power outages. God forbid that global automation-acceleration-expansion be hampered by actual limits. This has led to an acute interest with how to create ‘offline’ CBDC that can still operate when the systems crash

Paternalism and authoritarianism: this critique is only nascent within the mainstream, and it really depends on ‘programmability’ actually becoming a thing. That said, there’s definitely some effort being made by the leaders of some CBDC projects to distance themselves from accusations that CBDC would be tool to micro-manage people’s spending

Reflection 2) Four intersecting dualisms to map CBDC

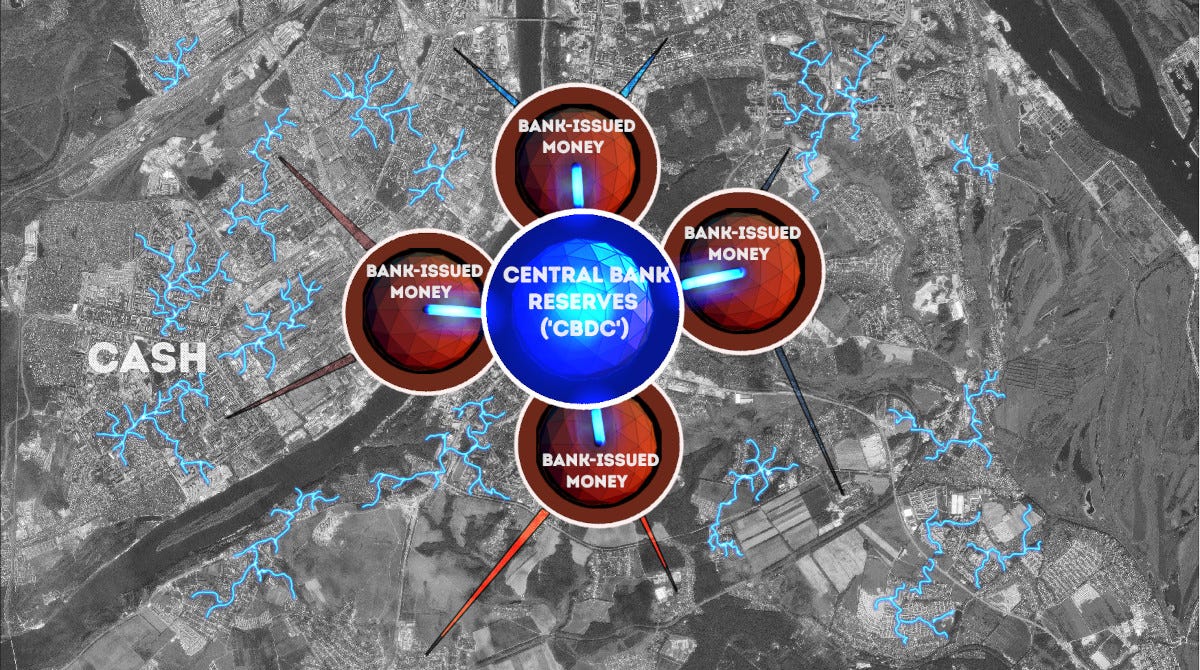

In my piece Paymentspotting, I represent the monetary system visually by showing the central bank hovering over society at the apex, with commercial banks plugged into it below, and then people and companies plugged into the commercial banks via accounts, but also having access to cash. If we had to take a helicopter and fly above this structure to look down on it, it might look like this:

The CBDC debate can be illuminated via four intersecting dualisms that can be mapped onto this picture:

Layer 1 money vs. Layer 2 money

Public money vs. private money

Physical money vs. Digital money

Passive agency vs. Active agency

The first two dualisms concern the structure of the monetary system, which is constructed in layers. The first layer of money in our society is issued by the state via the central bank, while the second layer is issued by private commercial banks (there are other layers, but let’s leave those aside). So, the primary option most people face is whether to use Layer 1 public money or Layer 2 private money. The latter can be though of, metaphorically at least, as bank-issued ‘casino chips’, but those derive their power from their tethering to Layer 1 state money, which acts as an anchor.

Dualism 3 concerns the form in which the money tokens in these different layers take. The Layer 2 money issued out by commercial banks is digital, whereas the Layer 1 money issued by states has both a digital and a physical form. As mentioned earlier, the banking sector has access to the digital form - central bank reserves - whereas we in the public only have access to the physical form - cash.

Prior to CBDC discussions, the original ‘cashless society’ debate was always about whether individuals and firms would be pushed into complete dependence on Layer 2 private digital money, while the Layer 1 public physical money faded away. There are (at least) two meta-processes going on there. In the first instance, that’s a privatisation process. In the second, it’s an automation process, because digitization is a core component of modern automation.

But what about Dualism 4? What is ‘passive agency’ versus ‘active agency’? I use those terms to refer to the account given for why big players do the things they do. Big commercial banks, for example, always pretend to be passive: they claim that the public actively ‘demands’ cashless society, and that they, the banks, merely passively follow the trend like faithful servants. The reality, however, is the opposite. The public wants choice, but the digital payments industry has aggressively and actively pushed to shut that choice down for a long time, running propaganda campaigns against cash, lobbying against cash protection legislation, and undermining the cash infrastructure by shutting down branches and ATMs. They’ve been joined in this by Big Retail, the airline industry and many other institutions that have decided to actively shut down the option to use cash. This whole drive gets a lot of ideological support from Big Tech too.

Central banks, by contrast, have been passive when it comes to protecting the cash system: they stand there and let the banking, payments and corporate sector beat cash up, claiming they have to be ‘neutral’. The original push for cashless society then, is one in which the commercial sector actively undermines cash, while central banks passively look away. This has led to our aforementioned contradiction, in which the Layer 2 system is shooting itself in the foot by attacking its own Layer 1 foundation.

So, how do these dualisms add up to CBDC?

Global capitalism has always been a public-private hybrid, but while the balance of power between public and private sector fluctuates within it, it always wants more automation. Put differently, the structural forces in capitalism push far more against physicality in the monetary system, than than they do on public sector involvement in that system.

This is partially why central banks find it less outrageous to promote a CBDC than to actively promote the cash system. Promoting a CBDC might threaten certain elements of the banking sector, but it doesn’t threaten corporate capitalism more generally. Amazon execs don’t care about whether their customers pay in the form of CBDC or Bank of America digital casino chips. They just don’t want cash, because they can’t automate it.

CBDC jells with the transnational automation drive, and if central banks do push one out, we’ll still have Layer 1 public vs. Layer 2 private money, but the former will now be available to all people and firms in a digital form. Central banks claim that this isn’t intended to replace cash, but in reality - given the non-negotiable automation fetish under capitalism - CBDC would de facto play into the existing war on cash. It would give nation states a plausible excuse to start shutting down cash infrastructure that they might have otherwise attempted to protect.

What we’ll probably end up with then is a new battle: public physical money versus public and private digital money, with the latter both being seen as keeping in sync with the ‘digital transition’ required for capitalist expansion and acceleration. The tension between public and private remains, but the digital forms will all gang up on physical, which will be presented as some kind of ‘horse cart of payments’ that only needs to be maintained while those who ‘still’ use it are slowly weaned off.

This leads us then to the most vanilla mainstream accounts of CBDC (which are often the most ideologically centrist too): we’re firstly told that cashless society is an organic bottom-up move driven by you and me, and that the banking sector has been passively ‘following’ this. Secondly, we’re told that central banks are now ‘behind’ the curve of this inevitable transition, so they too must now passively follow to keep up with the spirit of the times.

The key to disrupting this view is to politicise it, and to do this you have to assert that Big Finance-Tech has actively pushed for the domination of their Layer 2 digital systems. This allows us to spice up the dualisms by demanding, for example, an active push for Layer 1 state physical money: this is the Pro-Cash Movement, which seeks to counter not only the privatization of money, but also the far more powerful automation fetish. Cash is the ‘public bicycle of payments’ fighting to keep a balance of power against the (private and public) ‘uberisation’ of payments.

Alternatively, if you want to maintain the automation line while pushing against privatization, you can promote a more radical version of state digital money. Rather than slouching towards a half-assed watered-down CBDC, a government could actively push for a privacy-preserving form of ‘e-cash’ that’s designed to provide an authentic alternative to the banks without compromising public privacy. This is what the ACLU (USA), the ECASH Act, and Positive Money (UK) are suggesting.

There’s also a geopolitical version of this latter position. Countries in the Global South often have their own monetary systems subordinated to digital (US dollar) systems pushed by private sector players. If you’re a central bank in such a country, you’ll watch as your commercial banks partner up with players like Visa and Mastercard, which will extend the reach of the US state into your economy. In this context, providing an alternative, non-US form of payment becomes politically interesting. This is one of the reasons why CBDC pilot projects are of such interest to central banks in countries lower down on the global pecking order. Let’s turn to that now.

Reflection 3) Stranger Kings and the Global South

Having noted that the CBDC debate has been dragged into life by the systemic inertia in our interconnected global system, it’s important to acknowledge that our system remains - in many ways - fragmented. There might be systemic trends that apply the world over, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t sub-systems with their own political currents that might bend those trends towards more local objectives.

Many people suspect that CBDC is a ‘solution in search of a problem’, but the imagined problem varies depending on where in the world you are. In the case of technocratic folks like Augustin Carstens, who sit in the centre of global power, the imagined problem is that the global financial architecture is too fragmented, and is thereby constraining potential growth. In his mind, this calls for rebuilding it in a unified form that will unleash the latent potential, and he imagines that wholesale CBDCs could form an upgraded base layer for all of this. For people on the peripheries of power, by contrast, the problem may be that the global economy is not equal. It’s dominated by imperialistic players that preside over whatever ‘shared’ infrastructure there might be, so what may be required is ‘digital sovereignty’ for smaller players. Some are now imagining that CBDC could play a role in that.

The rest of this post is time-locked for four months, and during that time is exclusively available to paying subscribers. To continue reading, please do upgrade to a paid subscription, or alternatively come back in April 2024. I do hope you’ve enjoyed the free version. Brett

The global monetary system - in stylized terms - looks like a pyramid of pyramids. Each national system has a central bank at its apex, with commercial banks plugged into it, but weaker national systems will often plug into more powerful ones, like the US dollar system, which is used to make transnational hops between countries. This requires countries to hold US dollar foreign reserves, and to have emergency credit lines with the US. Woven into this are all the private payment infrastructures, like the US-dominated SWIFT network, used by banks to coordinate international payments, and the US card giants Visa and Mastercard. Those companies hover around the global ‘financial inclusion’ scene, trying to make inroads into countries where citizens use cash instead of relying on digital bank transactions. As local commercial banks enter into deals with the card companies to extend their own power, the card companies project the US state into countries where people have no political rights in the US.

During the 1980s, the meme of the ‘state versus the market’ was popularized, but this dichotomy contains two dubious assumptions. The first is the assumption that markets are not built on top of states. The second is the assumption that states-in-general can be separated from markets-in-general, and that geopolitics can be separated from geo-economics. Those binaries are false. The reality is that the US state backs the US market, and American corporations have far more power than many smaller governments do. In its push for global expansion, the US market acts to undermine the sovereignty of many countries in the Global South, and extends the influence of the US state in the process. Geopolitics and geo-economics are a continuum, and many geopolitical battles - say, between China and the US - involve strategic promotion of their own corporations. US officials want Visa to penetrate into foreign regions, and to project US power as a by-product of its search for profit. This is why, for example, the US development agency USAID actively collaborates with Visa.

This means, if you do find yourself as a politician in a small country, you’ll find that US agencies are already encouraging you to do ‘financial inclusion’ projects in collaboration with Visa, and you’ll probably also notice that your local banking sector sees an advantage in collaborating with those firms. As this happens, sovereignty is undermined, because your citizens become dependent on foreign firms.

In some countries, these firms might appear like the ‘Stranger King’. This is a term from the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins, and it refers to the situation in which a foreign force is perceived to offer citizens more protection than their own local political elites do. Those who believe in local democracy, however, see such Stranger Kings as a trap. This is a common theme in the African context, where local intellectuals will often speculate about whether there are ways to break away from the US-dominated international system, either unilaterally, or in multilateral arrangements with other African countries, or by playing the great powers off against other each. Inviting a Chinese payments network like UnionPay into your local markets is a subversive act in US eyes.

CBDC is now playing into this. One of the very first CBDC-style experiments was run in Ecuador between 2014 and 2018, when the government piloted a state-run mobile payments system, along with an open API that would allow an ecosystem of private players to build services on top of it. It was shut down due to lobbying and opposition by the Ecuadorian banking sector.

The former Ecuadorian central banker Andrés Arauz was one of the people behind the experiment. He sees CBDC as an opportunity to build a stronger national system in conjunction with community credit unions, forming an alliance that could compete against international payments firms that are collaborating the local commercial banks. It’s similar to the left wing vision of CBDC promoted by UK groups like Positive Money (see Zen and the Art of CBDC Analysis Part 1), but with an added geopolitical element: in providing an alternative to the banks, the state indirectly battles foreign domination.

It’s certainly notable that many CBDC pilots have begun in Global South countries, but in these countries we observe a contradictory combination of factors. On the one hand, officials in such countries are low down on the global geopolitical order, and often display ‘more Catholic than the pope’ behaviour in an attempt to suck up to the global powers. In this sense, the desire to run CBDC pilots could look like an aspirational attempt to appear modern and on board with the vision pushed out by the likes of the BIS. On the other hand, many of these same officials have rebellious thoughts behind closed doors. They are well aware of just how little power they have globally, and having less seats at the table can also mean they have less to lose by trying to create an alternative vision. It doesn’t take much for Swaziland to announce that it’s experimenting with a national CBDC. It’s not like it has any power in the international banking scene, so it has more freedom to be experimental.

(As a side note, this is also partly why El Salvador was happy to take the gamble on making Bitcoin ‘legal tender’. Very few people in El Salvador use Bitcoin like that, but the Salvadorian president Bukele intended it as a geopolitical play to get favour from US libertarians, who might inject capital into the country. He had little to lose in that situation. In fact, it’s the Bitcoin community that has more to lose by being associated with an autocrat.)

Being able to recognise these dynamics is a question of position: a fintech analyst in London might assume that Visa and Mastercard are ‘good’ players that are geopolitically aligned with the UK. If you’re sitting in Ecuador, however, that assumption may not be shared.

Reflection 4) ‘Exnomination’ puts both crypto and CBDC into the spotlight, and the banking sector into the shadows

My favourite term from the French semiotician Roland Barthes is ‘exnomination’, or ‘outside of naming’. It refers to the process by which a power elite becomes virtually invisible by never referring to itself. True power ‘goes without saying’, and fades into the background as a kind of unquestioned default, and only deviations from that get noticed or mentioned.

I believe that a version of this plays out in the monetary system: the entire digital payments system is run by the banking sector, and in places like the UK their ‘digital casino chips’ make up over 90% of the money supply. Despite this, there’s no word to refer to that money, other than ‘deposits’, which makes it sound like its government cash that’s been stuffed into the bank. The fact that the banking sector is a gigantic money issuer that hides itself in plain sight leads to some serious issues in public understanding of money, and by extension, the CBDC debate.

For example, I recently spoke at the launch of Big Brother Watch’s new report on CBDC at the UK Houses of Parliament (see image above). The room was a mix of MPs, industry representatives and members of the public. During the Q&A, a man got up and insisted that CBDC was being pushed so that the government could spy on our payments to monitor for tax evasion. Implicit in his comment was the idea that the government couldn’t already do this by spying on our commercial bank accounts, but this is false. For example, the 2017 UK Taylor Review suggested pushing small businesses towards ‘cashless’ bank transactions so that the state could do tax monitoring.

There was something else implicit in the man’s comment. He seemed to think that any future CBDC would be the only digital pound available. He was either unaware that the banking sector already issues digital pounds, or he thought that the state would outlaw those and only allow us to use CBDC, thereby turning it into a giant state surveillance system. Capitalist nation states, though, have no intention of destroying their own banking sector by outlawing bank accounts. The UK government is constantly trying to promote its financial sector to the world, and any politician that tried to go against that would be seen as totally unhinged, and would almost certainly face massive backlash.

What’s extraordinary about all this though, is just how invisible the banking sector is in people’s minds. Even the official names used for CBDC projects, like ‘The Digital Euro’, imply that there’s not already some digital Euro that exists. This is absurd, because the majority of the Euro system already takes the form of bank-issued digital euros.

CBDC is highly visible - and causes much consternation - because it’s a deviation from the unnamed - or ‘exnominated’ - default, and is seen to be a ‘new’ digital currency. It’s also often erroneously seen as the ‘first’ fiat digital currency, as if central banks were following suit from the crypto world by releasing a new centralised ‘coin’. This is reflected in much public discourse: Big Brother Watch, for example, uses the term ‘spycoin’ to refer to the UK CBDC proposals, while others have called it ‘govcoin’, or ‘Britcoin’.

The belief that the real battle is actually between CBDC and Bitcoin, rather than between the dualisms described in Reflection 2, is actually very common. Almost every article written about CBDC in 2019 or 2020 had to make some obligatory reference to Bitcoin, which was going through its own hype cycle at the time. Not only was it assumed that Bitcoin was connected to CBDC in some way, but journalists would often lump in the other shiny new thing - stablecoins. They’d say stuff like ‘with the rise of new digital currencies like Bitcoin and stablecoins, central banks are trying to keep up with CBDCs’.

In essence, they simply took everything that wasn’t exnominated, and placed them in an arena together. They’d present a ‘new world of digital currencies’ battling each other for dominance while cash faded away in the background. This January 2023 BBC article, for example, weaves together the UK government’s plan to become a ‘crypto hub’ with government proposals for a CBDC ‘digital pound’, stablecoin regulation, and the ‘crypto winter’ that affected Bitcoin prices. The implication is that they are somehow all related.

In keeping with the exnomination theme, one of the issues here is linguistic. The vast majority of our digital money takes the form of digital casino chips issued out by the banking sector, but people have learned to associate the term ‘digital currency’ with crypto-tokens. This means that when people hear the term ‘central bank digital currency’ they associate it with Bitcoin.

In reality, however, Bitcoin barely qualifies for mention in this debate. Bitcoin is a system of limited edition digital collectibles with monetary branding, but they totally depend upon being priced as assets in the actual monetary system. This is what furnishes them with a property called ‘countertradability’ (see Designing the Moneyverse), which in turn gives them certain ‘moneylike’ properties, but they don’t pose any structural threat to the central banking system.

Insofar as central banks pay attention to Bitcoin, it’s either to castigate it for being a new mechanism for money laundering, or it’s to warn about the consumer protection risks that come with the massive speculative market that surrounds it. Structurally, though, there’s no visible dent in the global banking system as a result of Bitcoin. If anything, it’s led to an increase in bank payments, as people make bank transfers in and out of their crypto trading wallets.

Perhaps even more un-enlightening than the ‘CBDC vs. Bitcoin’ binary is the ‘Bitcoin vs. Stablecoin’ one. As I noted in How to Build an Origami Stablecoin:

(the term) ‘Stablecoin’ was chosen because it was… supposed to mean ‘like Bitcoin but stable’, but a better taxonomical strategy would be to say ‘like Paypal but in decentralized digital bearer-instrument form’.

The real battle is not CBDC vs. Bitcoin, or Bitcoin vs. Stablecoins. In most cases, it’s also not CBDC vs. Stablecoins. It’s CBDC versus ‘bank-coins’, the digital casino chips or ‘deposits’ pushed out by the likes of Barclays and Bank of America. In keeping with the observations in Reflection 3, however, it is worth noting that a ‘decentralised PayPal’ pushing out Layer 3 US dollars is going to be seen as a threat to any country with a weaker currency in the global system. It authentically is a problem for a South African central banker if my family starts using US dollar stablecoins instead of the South African rand. In this geopolitical context, there is a chance that stablecoins have some bearing on the decision to implement a CBDC, but this is not a battle between ‘crypto and the state’. It’s a battle between the US dollar in crypto form, and weaker states.

Reflection 5) Beware the Public-Private Dualism

In November 2022 Edward Snowden put out a tweet saying ‘it begins’. He was referring to a ‘digital dollar’ pilot being run by the New York Federal Reserve and a range of banks. The tweet got over 18 thousand retweets, but what was ‘beginning’ according to Snowden? His statement was designed to play into popular concerns around a possible new state CBDC. He was implying that some previously unprecedented attack on freedom was about to take place.

In reality, nothing ‘new’ was really happening. The project he linked to wasn’t instigated by the US government. It was instigated by the commercial banking partners, the ones who already dominate the digital payments space. The project they are working on is the Regulated Liability Network. It’s jam-packed with commercial players, and it’s just the latest in a decades-long process to streamline the public-private nature of the monetary system.

I’ll reiterate something I’ve already noted. When someone like Augustin Carstens puts out a vision of a ‘unified ledger’ underpinned by wholesale CBDC, he’s just advocating for a more accelerated version of our existing system. We already have ‘wholesale CBDC’, and it’s the system that banks use to settle transactions between themselves. Augustin and his crew are mostly just interested in a kind of IT upgrade or streamlining process where they make the interlocking public-private parts of our system more ‘frictionless’, so that everything can speed up a gear. The project linked to by Snowden is the same. It’s designed to promote the commercial bank money payments infrastructure, by streamlining settlements between banks with an upgraded version of central bank money.

The key mistake made by many people - including Snowden - is in assuming that the automation drive we see under capitalism is guided by political leaders’ desire for domination, but in reality it’s guided by the corporate profit-motive, and for many politicians success rides on supporting that. Political domination can emerge as a by-product of the infrastructure pioneered by those seeking profit, and co-evolve with it, but it’s not necessarily the driving force.

I spend a fair amount of time in mainstream circles, and I’ve almost never encountered a central banker who is gung-ho enthusiastic about CBDC. Rather, they feel a slow-motion gravitational slide towards it, which is a result of the much larger global automation vortex, but what they primarily care about is keeping their jobs, and that depends on them keeping the monetary system stable and friendly to the private sector. Central banks are like private clubs that manage the relationship between the state and the commercial banks, acting partly for both, and this is a constant balancing act. Every mainstream CBDC proposal right now is purpose-built to walk that fine line. This is why those proposals most likely will:

Include measures to limit the power of CBDC: for example, by placing limits on how much the public can hold

Include measures to bring the private sector in: for example, by allowing the banks to insert themselves between any future CBDC and the public

Focus on ‘wholesale’ CBDC that doesn’t interface with the public, and that’s actually designed to boost the background efficiency of private systems

So, if you ever find yourself in the room at these CBDC discussions, you’ll realise that the vibe is one of sluggish inertia criss-crossed with confusion about how it does or doesn’t relate to crypto-tokens. My contribution to these discussions is often to remind people of the actual structure of the monetary system, and to forcefully promote a balance of power within it, not only between public and private, but between physical and digital.

Brett, I hope you're following by reading each chapter of my new 2024 updated and expanded edition of The End of Money and the Future of Civilization. The first three chapters have already been published on my website and Chapter 4 will follow shortly.

Excellent and illuminating analysis, Brett, as ever. Thank you.