Why you can swap Bitcoin for many things, but not buy anything with it

Understanding the phenomenon of crypto countertrade

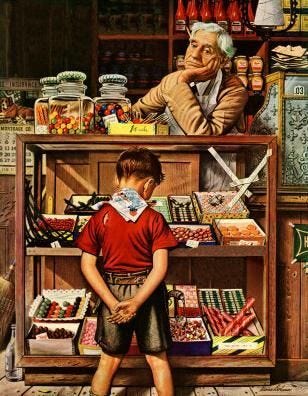

I created the image above to illustrate the concept of ‘countertrade’, which is crucial to understand if you wish to see how crypto-tokens like Bitcoin work. The image is intended to show that someone who apparently ‘pays’ with Bitcoin for something like a camera is actually - in the final analysis - paying with US dollars.

I will explain this in the post below, but I have been motivated to write this because of the enormous amount of misinformation that is flooding the media about Bitcoin right now. If you follow the news you will have undoubtedly come across many excitable pundits claiming that the ‘digital currency’ is being adopted in place of normal currencies. This post is designed to help you see through that by introducing you to the phenomenon of countertrade. This will put you in a far better position than the vast majority of these analysts, but before we can do that I must ask you to imagine yourself as a small child wandering around a supermarket with your parents.

The supermarket distinction

From an early age a child learns to distinguish between money tokens, on the one hand, and everything on the supermarket shelves on the other.

Imagine yourself as a kid entering a supermarket after being given pocket-money of $25 from your parents. You hold the money in your hand, but as you look at it your mind leaps to things beyond money. Perhaps you think of sweets, or toys, or children’s magazines that you might find on the shelves. You recognise that those are all different objects with different uses made by different companies, but you also recognise that they are accompanied by prices, all of which carry a common symbol, and which enables a comparison between the goods.

As you wander through the shop aisles, you make calculations of possible combos of goods you can capture with your $25. Perhaps you can get five packs of sweets for $5 each, or a toy for $15 along with a magazine for $10. Perhaps you should use the whole $25 for a football. The psychological process is not so much one in which you compare the money against the goods. Rather, you are sizing up the goods against each other, via the money.

The monetary system has a very intriguing property of being all-present - all the goods carry prices - and yet curiously invisible: your mind is preoccupied with calculations about which goods are the best value relative to other goods. When you are assessing the price of a good, you are - subconsciously at least - actually comparing that good to other goods via a common measure (this is sometimes referred to as the ‘unit of account’ function of money). Indeed, it is almost impossible to assess a price without having pre-established notions of what you might expect other things to cost. For example, the reason why you know that a price of $500 for a cup of coffee is absurd is simply because you can see that bread can be obtained for $5, and pricing is a relational concept in which goods tied under a common monetary web are compared. Your spidy senses will automatically reject such an excessive coffee price purely through an intuitive awareness of how the other goods are measured.

Thus, when you - as a kid in a supermarket - ask yourself a question like ‘Is this football really worth my $25’, you are implicitly processing background thoughts like ‘Is this football truly equivalent to five sweets, or a toy and magazine’.

How countertrade works

Imagine yourself mulling over these options in the supermarket but then being told by your parents to hurry up. They wish to leave the store, so you need to make a choice in a hurry. Flustered under pressure, you rashly choose to spend the entire $25 on the football. As you run out, though, you are suddenly overcome with buyer’s remorse, realising that you don’t really like football, and would really prefer some other combination of goods. You suddenly turn around, rush back into the store and tearfully try to explain the situation to the cashier, holding up the ball and pointing to the toy and sweets section. The cashier understands what has happened, smiles and says, ‘oh, so you want a toy and sweets instead?’

At this point the cashier has two options. They can either take the ball back and refund $25 to you, thereby putting you back into your starting position. You can then dash around the store with the money, like before, and collect up the new goods to take back to the check-out. Alternatively, the cashier can take the ball back, but hold onto the $25, and just tell you to go collect goods of equivalent combined price. Let’s say the cashier goes for the latter option. You hand back the ball, and go collect a toy and two sweets.

Let’s now add a curveball element to our thought-experiment. Imagine an alien is watching this interaction from outer space through a powerful telescope. What do they see? They see you handing over a ball to the cashier, and then getting a toy and sweets. If the alien was lazy in their analysis, they might come to believe that the ball is a form of ‘currency’, and that you just used it to to ‘buy’ a toy and sweets.

Of course, we know that what was really happening here was not a process of ‘buying’ toys and sweets with a ball. Rather, this was a process of swapping one good that cost $25, for other goods that cost $25. The technical term for this is countertrade. There are many forms of countertrade, but they all involve offsetting (or ‘clearing’, or netting off) money-priced goods against each other. A single act of countertrade is actually two monetary transactions squashed into the form of one non-monetary transaction: technically speaking, what is happening is that the child ‘resells’ the ball to the cashier for $25, and then uses the money credit to get new stuff, but it ends up looking like a ball being handed over for new stuff. The currency is still US dollars, not balls, but no US dollars need to be overtly handed over.

Digital countertrade

Let’s now change the scenario. Imagine yourself as an adult in the present day, and winning a lottery of $25,000. You are very happy about this, but now face a similar choice to the one you faced as a small child upon receiving pocket money. In the grand ‘supermarket’ of the overall economy there are many diverse goods being priced under a common monetary system. Should you spend the $25k on a combo of goods - for example, a holiday, a second-hand motorbike, some Apple shares, a high-quality camera and a vintage guitar? Or should you spend it on bigger items, like a car and a renovation of your house? Or should you throw it all into buying up one of those limited-edition Bitcoin tokens your trading buddies keep talking about? Here are three possible combos.

Let’s say on an impulse you do the latter. You go onto a site called Coinbase, which is like an online supermarket for digital collectibles. You hand over $25k for one Bitcoin token. Ten minutes later, however, you have a sudden moment of buyer’s remorse, realising that you really would prefer a vintage guitar and camera, along with a car.

There is no overt ‘cashier’ to run back to like when you were a kid. You can, however, go back to Coinbase and resell the Bitcoin to get roughly $25k back (assuming the price hasn’t changed dramatically since you logged on). You can then take that 25k and use it to buy the things you actually want.

Imagine, though, that you hold onto the Bitcoin, but find an online camera store that ‘accepts Bitcoin’ for cameras. You find the camera you want, but also notice that the online store has an option to toggle between US dollar prices and Bitcoin ‘prices’ for the object. The US dollar toggle tells you that the price is $5k. The Bitcoin toggle, however, says the camera is ‘0.2 BTC’. You browse around the site for a little, before returning to the camera, but upon returning see that the BTC ‘price’ for it has reset. It now says ‘0.21’. Five minutes later it says ‘0.19’. You toggle back to the US dollar. It still says $5k.

The reason for this is simple. The camera actually costs $5k. This is the real price. The store, however, constantly queries a Bitcoin exchange like Coinbase, asking how much Bitcoin would need to be sold to get $5k. This amount fluctuates as the dollar price for Bitcoin changes (reflecting Bitcoin’s relationship to all other goods, via the monetary system). If you opt to hand over Bitcoin for the camera, the store will take it and immediately sell it for $5k on Coinbase.

The alternative way to do exactly the same thing would be to just sell some of your Bitcoin for $5k and then hand it over to the store. What’s going on here is that the store is offering to do the selling of the Bitcoin for you, which is why they ask you for $5k worth of it. This is countertrade. The reason why the dollar price for the camera stays constant while the supposed Bitcoin ‘price’ for the camera doesn’t, is that the latter is not a price: it is a countertrade ratio. The money price for a camera is being offset against the money price of a Bitcoin collectible, leaving a residual swapping ratio between them. Because Bitcoin’s money price constantly changes through the speculative market upon which it is traded, the online store has to constantly change the ratio to maintain the $5k selling price.

Why this matters

Much of the rhetoric around Bitcoin is predicated upon the idea that it is challenging the monetary system. From a certain limited angle, it is. If a large number of people begin indirectly countertrading with dollar-priced digital collectibles, rather than directly purchasing things with dollars, it could affect the surface level of the monetary system. I myself have used Bitcoin for countertrade on many occasions.

But make no mistake. Just like a kid swapping a ball for toys does not undermine the Federal Reserve (which issues dollars that both are priced in), swapping a dollar-priced Bitcoin collectible for dollar-priced goods does not fundamentally alter the structure of the monetary system.

Indeed, crypto countertrade only works if Bitcoin first gets a dollar price in a speculative market, which in turn will enable it to be swapped with other things with prices in consumer goods markets. This is fundamentally different to an actual monetary system that is used to establish relative value between different goods in all those markets. What we can say, however, is that Bitcoin collectibles have very high countertradability, which is not a trivial property, and can be useful.

It is very important, however, to be able to distinguish between a countertrade object and a money token, but the ability to do this is very poorly developed right now, which is why the media is constantly full of stories of Bitcoin as ‘money’. Unlike a ball, which very clearly is not money, Bitcoin collectibles are surrounded by monetary language and branding, and come pre-packaged with monetary mythology (imagine a movable digital ball pasted over with images of coins). This makes them very easy to confuse with actual money tokens.

Bitcoin will only become a true currency at the point at which a kid (or adult) holding the tokens thinks about goods in a supermarket, rather than thinking of how much they can sell it for. The key hallmark of money is that when you hold it in your hand, your mind does not wander off to think of money, but rather thinks of goods on shelves. Right now, Bitcoin tokens do the opposite. They come from the digital ‘shelves’ of digital markets, and make people think about US dollars (or whatever other currency they're using). This means they can be used for countertrade, but not for ‘buying’.

To conclude, let’s use this to make sense of the recent news from El Salvador, in which President Nayib Bukele claims that Bitcoin is now a ‘national currency’ there. This is absolutely not true. Bukele is simple pushing his citizens to use Bitcoin for countertrade. Their actions are not going to establish ‘prices’ for goods in Bitcoin. Rather the money price of Bitcoin will still be established in a global speculative market (very far away from El Salvador and largely detached from the activities going on there), but will be available to use to calculate countertrade ratios for dollar-priced goods in an El Salvadorian store (El Salvador uses the US dollar).

Once you learn to see this, many more statements about Bitcoin will become much clearer. I will be publishing more guides like this to help you navigate through the language games the crypto community plays, so please do sign up if you’d like to hear more.

Ciao Brett, thank you for this post. I love the way you explain things and I would like to share some thoughts with you.

First: in your story you can easily change the word "Bitcoin" with "Euro". So the camera is still costing 5k and still the price in euro, which depends on the exchange rate US$/€, will go up and down while the one in $ will remain fixed. At the same time on another online store based in Italy the price for the same camera in € is 4k and doesn't change. But the shop offers its clients the possibility to pay in US$ and this price is moving up and down while the one in € never moves. Can we say that nor US$, nor € are "money"? Obviously not. So what makes these two currencies "money"?

Second: back on Jan 1st 2001 in Italy we abandoned the italian lira and adopt the €. For several months or years we weren't able to think to prices of what we found at the supermarket in €. We normally translated those prices we read in € back in Lire and only after the translation we were able to take our decision as buyers. After a certain period we got used to prices in € and we were no longer obliged to do a mental translation. How this inability transformed in new ability effects our perception of € as money?

Third: in Switzerland few know that there are two currencies: the Swiss Franc and the Wir franc <https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/WIR_Bank>. Wir franc is a complementary currency which exists since 1934. No other country accepts Wir franc but in Switzerland you are allowed to have banking account in Wir, borrow Wir franc, etc. Is Wir franc money and why?

Forth: Is it possible that the reason why bitcoin seems not money to you is because there is no sovran state which use bitcoin as its currency? And what about if a State tomorrow will announce that it's new currency is bitcoin? I mean it's only currency is bitcoin. Would this announcement trasforma bitcoin in real money?

Thank you very much again for the time you spend on your very smart newsletter.

Take care of yourself,

Marco

You said elsewhere that you think the primary function of money is the standard of value function, which is what this article is fundamentally about. But money-as-we-know-it has the standard of value and medium of exchange functions fused. In days of old, minted coins didn't even have prices on them, because their value was determined my the sovereign, and liable to change. In this case according to your definition, even those coins weren't money, because pure money is a pure measure.

So I find it very hard to say much definitive about money because its very essence seems to depend on context. So I wouldn't call bitcoin money, but I don't have a problem with 'using bitcoin as money' meaning that I can settle debts with it and move it around.

In fact I've notice that every market could be said to have its own money. As Marco points out below, the Euro is just a barter object when something is priced in dollars. This is because a dollar priced object signifies a dollar marketplace where the Euro is not money. I can also imagine non-market contexts when money itself seems to be used more like an object for countertrade...