Derivatives are simple but look complex. Money is complex but looks simple

How money hides itself in plain sight, and how we might get a birds-eye view on it

In the first edition of this newsletter, I suggested that while financiers know how to work with money, that doesn’t mean they know how money works. I used the analogy of a painter who might know how to paint elaborate scenes without ever knowing what chemical magic brings their rich blue and yellow paints to life.

The artist Alex Schaefer paints banks on fire

This phenomenon - of knowing how to manipulate money without knowing what it is - can be found in society more generally. Schools, for example, might teach ‘financial literacy’ to kids - which entails learning to budget, save, and invest - but these lessons in ‘managing money’ basically teach people to be proficient but uncritical users of a system that’s never questioned and barely explained. It’s like being given a surface-level instruction manual on how to interact with a vast black box, rather than a behind-the-scenes engineering schematic of what’s inside the box.

The ‘black box’ system I refer to above is the monetary and financial system, but really this is a whole series of interlocking sub-systems arranged in elaborate circuits across the globe. Most financial professionals occupy extremely niche positions within one or other of these sub-systems, and get paid to focus solely on that position, which is why many of them actually have very little understanding of the bigger picture.

Nevertheless, working ‘within the system’ does offer opportunities to catch brief glimpses of its internal structure, and when I was working as a derivatives broker, I began to intuit some of this deeper architecture of global finance. On a day-to-day basis I was learning all the technical jargon and techniques associated with derivatives trading, but - when I took a step back - I began to sense that most of the operations of finance are political and social rather than technical and individual.

Investment banks like to present themselves as purveyors of impossibly sophisticated methodologies and technologies of finance - visualised as a trader sitting behind an array of screens full of mathematical equations, spreadsheets, code and graphs…

Simon Roberts takes photos inside investment banks

… but while these individual traders might be competent, they have their power greatly amplified by their position within a political beast with enormous capital and elite social networks of influence. These banks can move markets and get big deals through their sheer size (and their ability to spend money on buying expensive meals at exclusive restaurants for their clients). They form oligopolies to dominate. They have highly-paid lawyers who write contracts that turn the odds in their favour.

Many people, though, fall for the false idea that traders at Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley get wealthy because they are individually very clever and understand how to read complicated graphs and market patterns. After all, look at all the numbers and things on those screens!

Many people are also prone to falling for the idea that to achieve ‘financial freedom’, all we need do is start trading and investing like those investment bank traders. For the everyday person, mystified and enticed by the glamour of the sector, there is a huge market of pseudo-scientific trading literature - essentially self-help books - about how to decode the secret patterns in graphs in order to ‘beat the market’.

Indeed, sometimes when I tell people - especially men - that I used to work in derivatives, they start to quote this literature to me, puffing up their chest and getting a serious tone in their voice as they tell me about their ‘day-trading’ activities on the stockmarket, or their spreadbetting account. Some believe they’re using the ‘tools of the masters of finance’ to rebelliously overthrow them and escape the grind.

More often than not, however, it is the masters selling them shoddy illusions. After I left the world of derivatives brokering (see the last post to get the basics on derivatives), I worked briefly as a consultant for a spreadbetting firm, a firm that specialises in flogging derivatives in a disguised form to small-scale amateur traders. Most investment banks wouldn’t dream of trying to package bets for some guy with £2500 in capital (£25 million maybe, but not £2500!), but if a ‘spreadbetting’ firm wants to plug into the investment bank and then resell betting products to that guy (like a small corner store resells goods from a wholesaler), then that works for them.

In order to attract amateur traders, such firms cultivate the idea that it is heroic to launch yourself like a crusader against the market. They do this because they know that - much like people who enter casinos on average will lose - wannabe traders will on average be like Don Quixote, charging imaginary market formations they see in graphs whilst simply handing over money to those with more institutional power - which is the spreadbetting firm itself, and the investment banks it plugs into. These firms cultivate a myth of the trader, puffing up their egos in order to harvest their money. Here is a classic example of this ego-pumping:

When people ask me for investment advice, I turn them down, because I have no interest in teaching someone to chase after market fluctuations like a cat chasing after a shiny bauble on a piece of string. The way to ‘beat the market’ is simple: run a huge bank with enormous political power. Finance has got very little to do with graphs (although type ‘finance’ into a Google search and you’ll see a lot of those), and if you’re spending your time trying to decipher them, you’re probably on the losing side. That imagery is a smokescreen.

So, if you are subscribing to my newsletter in the hope of becoming a better investor or day-trader, turn back now. We’re on a much deeper journey beyond the smokescreen.

Derivatives are not complicated. Money is.

So let’s take a peek behind that screen. The traders in the video above specialise in, for example, buying and selling claims upon future money stemming from the activities of particular enterprises (or entering into bets on those claims). For example, a person who trades shares in the oil company BP is - in essence - buying and selling a portal into a massive financial conduit that looks like this:

This is a diagram that me and couple of others from OpenOil made a few years ago. It shows BP’s global subsidiary network. BP shares are claims upon the BP mothership, which in turn is tethered to a fleet of over 1000 corporate subsidiaries embedded in around 80 countries across the world. I’ll delve into this in later articles, but these company chains hold ownership over thousands of things like this:

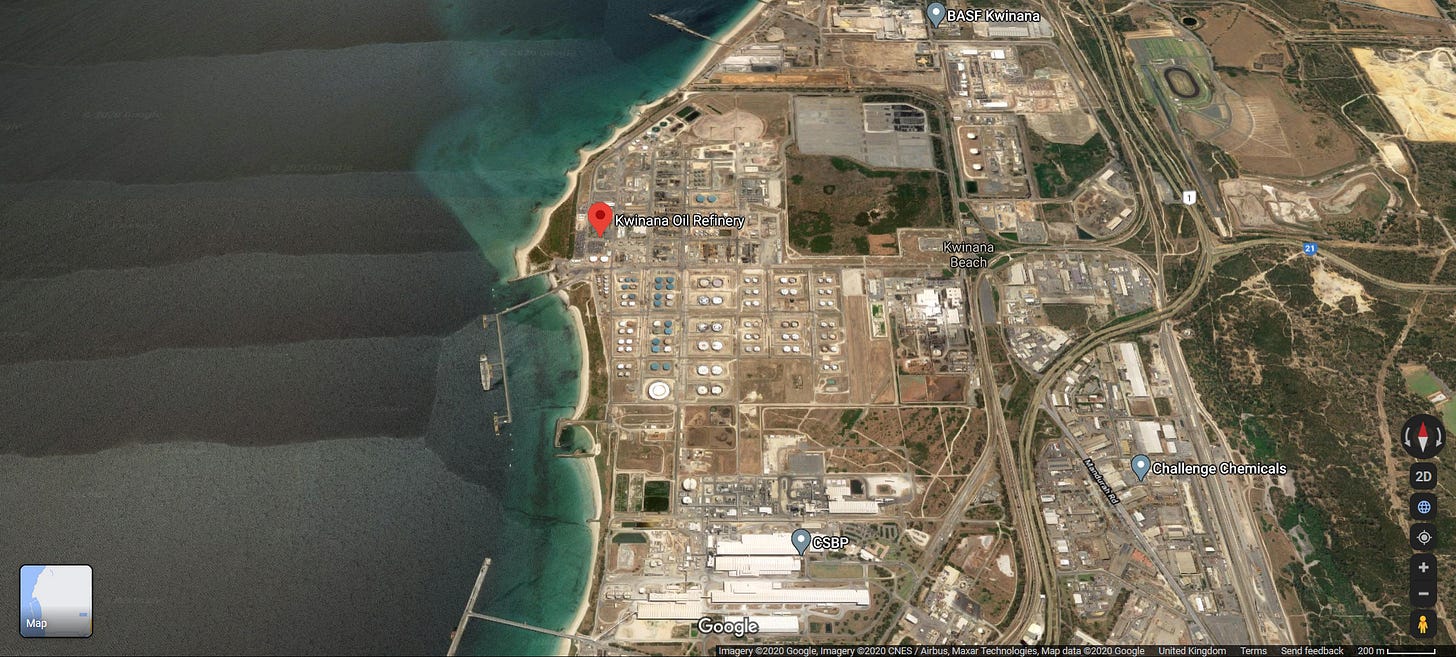

Which send oil to facilities like this…

Which send products to places like this…

… where a late-night trucker might fill up whilst handing over $80 in cash to an attendant.

At the same time, a late-night trader might look at a trading screen - provided to them by some spreadbetting firm - to see this…

… which is an abstract representation of the activities of traders buying and selling these portals into the imagined future money generated by the BP global mega-complex.

And as that trader sits there fixating on whether to place a bet, studying the shape of the graph, they may believe that their art-form is complex, like a science of some sort.

But I’ll tell you what is far more complex. How does a mega-corporation like BP operate in nearly 80 countries, each with different currencies embedded in networks of people with vastly different cultures, and yet end up with a single share price quoted in a single currency that a trader can look at? There must be a vast system to harmonise those separate currency networks into a single one.

But even deeper than this, how exactly do those different units of money in those different places - commanded by those subsidiaries - mobilise people to dig holes in the earth, or to leave their home to work on an oil rig? How does a money token printed on cotton paper induce a gas station attendent to give the trucker gasoline?

Put a different way, this global BP mega-complex only works insofar as money works, but do we know how money works? The question often seems so basic that it constantly avoids our attention. If asked, that late-night trader might look at you like a professor might look at someone asking them a kindergarten-level question. They might trot off a series of cliches about the so-called ‘functions of money’, before returning to the ever-so-sophisticated arts… or science… of trading futures contracts, or whatever.

But appearances deceive us. Derivatives are just crude instruments that look complicated, whereas money is an incredibly sophisticated and complex system that looks very simple. This is why it constantly eludes our view.

Distracted by the surface

One reason people think money looks simple is that the monetary system as a whole is largely invisible, but it does have visible surface-level artefacts that can be seen, and which - indeed - look simple. For example, we can see cash tokens…

A cash token is a physical state money token, but a money token is not a money system (FYI - I dive deep into this topic in my first subscriber video here, where I look at the fetish that the media has for fixating on money tokens rather than money systems that activate them. Subscribe for access!).

What other surface-level artefacts are there? Well there are a whole array of interfaces, such as ATMs in the wall, bank branches, and the screen layout on your internet bank account, where you can see numbers representing some kind of digital objects under your control.

Well, actually those numbers are records of promises made by a bank - let’s call them bank IOUs, or bank money (they are, in fact, an entirely different form of money to the cash token, albeit they are symbiotically linked and operate under a common political and legal structure). These units are recorded in bank datacentres, but the media almost never shows images of those datacentres. They might, however, show images of another surface-level artefact: plastic cards, which are devices we use to communicate with those datacentres.

The internet is rammed with photos of these surface-level artefacts, interfaces and communication devices, but all of these are meaningless without the behind-the-scenes architecture that either activates them, or that they plug into. Much of what this newsletter will be doing in subsequent months is jumping back and forth between these surface-level elements of the monetary system that we can touch or see, and the structures - political, legal, cultural, and technological - beyond them that remain out of view.

From 2D to 3D

One of the first strategies for revealing these structures is to build zoomed out ‘birds-eye view’ schematics of them. This was something I initially began doing on my Youtube channel, where I began a series called The Landscape of Modern Money. In the first video in the series I sketched out a 2D drawing of the major categories in the money system.

It’s a useful - albeit rough - video (and I recommend watching if you want to get a head-start on this stuff) but my sketches were not exactly birds-eye view, unless the bird was looking directly downwards on the earth…

Still, this 2D image was initially ok to spacially convey some of the big concepts. For example, it shows the three layers of modern money:

State money

Bank money

And… for want of a better term… money issued by ‘plug-in’ institutions like Paypal

It also differentiates between different forms of state money:

Cash

Reserves

It also tries a crude representation of the ‘War on Cash’ (a term I use to talk about how the cash form of state money is being attacked by purveyors of the digital form of bank money), and hints at the possible emergence of ‘central bank digital currencies’ (CBDCs), which would add a third form of state money to the list above.

I will be returning to all these themes in far more detail in due course, but I wasn’t entirely happy with the 2D structure, so started going 3D in my subsequent videos, where I also started introducing other meta-themes like cryptocurrencies and ‘stablecoins’ (themes I will be returning to in future newsletters in due course).

The ‘hovering banks’ image

The emergent 3D visualisations are starting to look more like true ‘birds-eye’ view. We have a country with a landscape and cities and people, and then an abstraction of the banking sector and central bank, which ‘hovers’ above the earth a bit like a fleet of flying saucers, or a city in the sky.

In the next newsletter, I’ll start labelling the different parts of this picture, and explore the origins, meaning and limitations of this ‘hovering banking sector’ image. I’m going to work with it for a while to build out basic animations of a whole series of monetary operations and phenomena. Catch you next time!

DFMM No.1 Wooden promises for digital money

Last week I put out the first Dispatch from the Frontiers of Modern Money. It’s an hour-long deep dive into the Tenino Wooden Dollar, a small community currency system in Washington. News outlets were picking it up as a heartwarming novelty story about a small town issuing its own currency - printed on thin pieces of wood - in response to hardship caused by the Covid crisis. They sent reporters to investigate it, but their reports often missed out all the most fascinating dynamics of this monetary experiment, mostly because they kept getting distracted by its most visible element - the wooden tokens. To get access, please do subscribe!