Designing the Moneyverse

A choose-your-own-adventure map for hacking the future of money

Premium Subscribers can find the audio version here.

There’s two reasons why this newsletter is called Altered States of Monetary Consciousness. The first is straightforward. I’m interested in helping us to think differently about money. The second is deeper. Money is the nervous system of the global economy, and - like any nervous system - it’s a core contributor to any emergent ‘consciousness’ that develops in and around that system. So, if you feel that maybe the global economy is like a numb, delusional and paranoid wreck walking towards oblivion, it makes sense to consider how we might alter the state of its nervous system.

When you look at something bad in our economy - such as the mass dumping of plastics into our oceans - you face a question as to where that badness emerges from. Activists might imagine that the source is the corporate sector, with its corrupt or callous executives. From another angle, however, corporations are just conduits for the financial sector. After all, most corporations are owned by large investment managers like BlackRock and Fidelity that are acting on behalf of players like pension funds and insurance funds. Those players, however, will always claim they’re acting on behalf of their beneficiaries, which may be you or me. Put simply, the financial sector claims to exploit the world on behalf of us, making us the source of the problems we revile.

The reality, as always, is much more complex and murky. The first thing to come to terms with is the fact that the monetary wiring of our global economy is one that separates us all from our actions. At scale, monetary systems reduce our relationships to each other, and to our ecologies, to numerical ratios. When a monetary vortex is your primary means of survival, it becomes as if you’re tied into a nervous system that has dulled out its pain receptors and can only ‘feel’ one type of thing - profit. We’re plugged into a systemic entity that might coordinate our action, but its inability to sense anything except monetary gain means it steers us in a very particular direction.

Some people claim that this state of disassociation - in which we’re guided solely by monetary incentives - leads us to utopia, while others claim it leads us to destruction. Either way, the fund managers and corporates will say they have no choice: if they don’t act towards maximizing monetary profit, they’ll be outcompeted and destroyed by the market. So, if you ever hang out in mainstream finance circles (like I do), you’ll notice that most analysts suffer from a bad case of ‘capitalist realism’. This is a term, coined by the late Mark Fisher, that refers to the state of mind in which it’s literally inconceivable to imagine any mode of action that doesn’t involve optimising for profit and growth.

This means, when faced with the myriad problems of the planet, most mainstream analysts will never allow their minds to consider a deep level recoding of our system. Rather, they’ll default to some altered variant of their existing principles. They’ll imagine that ecological degradation can be resolved with ‘sustainable growth’, and that inequality can be solved by ‘inclusive growth’. In essence, they tacitly acknowledge that we live in a system that’s numb to anything except profit, so rather than expecting our system to feel ‘pain’ at the pollution of the oceans, a sustainable growth proponent will seek to make it pleasurably profitable for our system to create a solution. Make it profitable to protect the oceans, or to fight climate change, or to combat inequality.

To people like me, that looks a helluva lot like a shallow form of wishful thinking. This is why we allow our hearts and minds to consider deeper forms of systemic change. This leads to the question of whether altering the monetary system - and it’s core institutions - might be a good vector for doing that.

It’s a controversial question, and there’s no obvious answer. Marxists, for example, have long had a bias towards imagining that the problems in our system lie in the relations of production (who owns what and who controls what in the vast interdependent economy we’re all plugged into). They’re not always particularly interested in the monetary system that holds those relations together, and through which the profit of those relations gets realized. Generations of monetary reformers, by contrast, often ignore relations of production and ownership, and believe the problem lies in the monetary system itself.

If we were using a biological metaphor, we might say that the former imagines the problem to reside in the relations between the organs and cells of the economy, while the latter imagines it in the nervous system. In reality, this binary is false. You cannot separate out the logic of the monetary system from the economy around it, any more than you can pull out your own nervous system and observe its logic detached from your body. This is something you always have to bear in mind if you ever dare to mess with the monetary system. So, let’s dare to do that.

Altering the monetary nervous system

I have a long history of taking part in alternative monetary experiments. I’ve worked on small local currencies like the Brixton Pound, have participated in community ‘time-banks’, and was an early member of the Bitcoin community. Now I’m active in the new-wave of mutual credit currencies (see Zero is the Future of Money).

Over the years I’ve encountered all sorts of people - from retired engineers, to bushy-tailed students and cocky entrepreneurs - who’ve told me that they’ve figured out the ‘perfect’ money system to replace our current one. That’s always a red flag, because money cannot be designed with a-priori principles derived from the cosmos, and it’s not supposed to be ‘perfect’. Money might be our economic nervous system, but it has co-evolved with everything around it, and - like your own nervous system - it’s not strictly ‘replaceable’ by one that’s designed better. To replace it you’d actually have to re-grow our entire economic organism, and that might end up looking very different to the world you have around you right now. Anybody that’s imagining a wholesale replacement of one monetary system for another, and is not expecting the body to die in the process, is… well... delusional.

So, if you’re ever designing an alternative monetary system, you cannot start from the assumption that it will exist in isolation from our existing one. Rather, you’re going to have to try graft it in as a sub-system, and maybe - if you’re really good at doing this - it might start to blend in and shift, ever so slightly, the economy around it. It’s like grafting a partial new nervous system into an existing body and seeing the muscles move a little in response.

Bitcoin is a fascinating and problematic example in this regard. Its most hardcore proponents - like Max Keiser below - often imagine it as a ‘perfect’ system in isolation from our standard system:

In reality, almost everyone perceives Bitcoin as something you buy and sell for dollars, rather than something you strictly use as money. In a sense, it’s almost completely absorbed - or ‘grafted’ - into the our normal system and cannot be analysed outside of that context. It may offer us new possibilities (see section 2 below) but it remains highly questionable whether it has truly altered any deep element of our economy.

That said, I always try to be supportive of people who attempt to build alternatives. It’s exciting to broaden one’s mind beyond our existing monetary universe, and to expand it into a multi-verse, or moneyverse. In my Unboxing Alternative Currency series, I do deep dives into different attempts people make at doing that, from local voucher systems to crypto-tokens and game currencies. When categorising these, we can split them according to:

Purpose: What the goal of the alternative is

Paradigm: The broad set of principles that are applied to achieve this

Parameters: The more specific variables that can be tinkered with to fine-tune it

Participants: Who the users and issuers are

So, in the spirit of helping any aspiring money hackers, let’s take a trip through each of these. Think of this as a choose-your-own adventure, where each decision leads to a new set of decisions.

Decision 1) What’s the purpose of your alternative?

People who build or support alternative currencies inevitably have a justification for why they do it. Normally it’s got something to do with liberating humanity, rebuilding communities, restoring spiritual balance, promoting economic development, regenerating our natural world or protecting us from some evil.

Of course, the vision for a better world that makes sense to one may not make sense to another. That’s because people differ in what they imagine the problems of the world to be, what they perceive to be source of these problems, what they imagine as a desirable alternative situation, how they imagine we’d get there, and how all of this relates to their own emotional world and attempts to survive in the existing economy.

Needless to say, you’ll have to choose an outward-facing message to the world about what you’re seeking to achieve. Here’s some possibilities:

Bypassing existing institutions and distributing power differently: if you believe that our system centralizes too much power in an oligopoly of banks, corporations and states, you may want to devolve power away from them. In general this political project goes under the name of ‘decentralization’, but there are different versions of the term. In crypto-currency circles, ‘decentralization’ tends to mean ‘creating a planetary-scale system controlled by nobody’. An older meaning of ‘decentralization’, though, is ‘breaking down one large centrally-controlled infrastructure into many smaller locally-controlled ones’. This latter promotion of localism is common in many older alternative currency systems

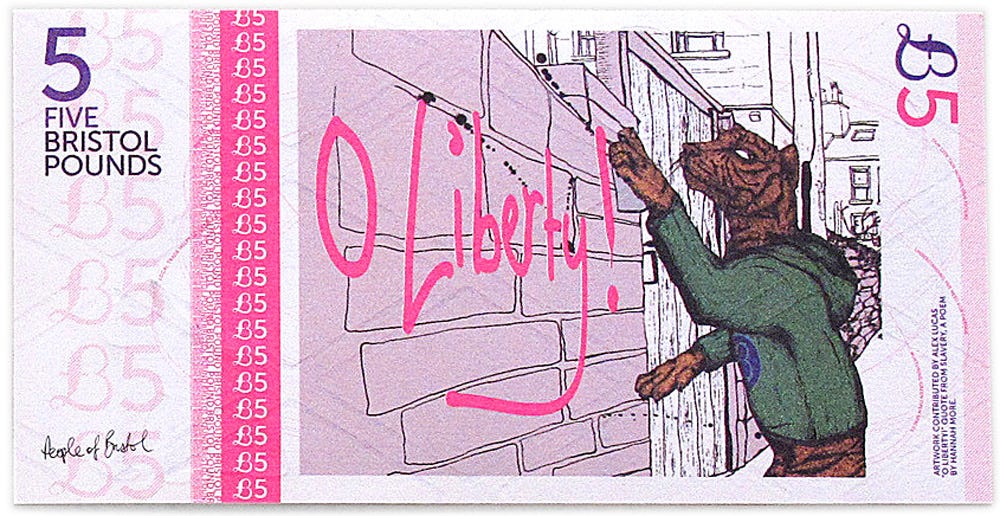

Promoting community: A localist project like the Brixton Pound may seek to strengthen a deprived community in a single neighbourhood of a city, but not all ‘communities’ are local. For example, many crypto libertarians are currently very excited about the concept of the ‘network state’, imagining transnational communities that align on values, rather than geography, using a common crypto-currency

Promoting (counter-cyclical) resilience: Not all alternative currencies seek to replace one system with another. Mutual credit systems like Sardex, for example, seek to create a complementary addition to our existing system, and one that provides a safety-net that can kick in during times of crisis. In more political terms, these systems create counterpower to our existing ones, seeking to balance them out

Privacy and ‘censorship resistance’: Standard digital money systems are controlled by banks and corporations, and extract huge amounts of data while enabling the ledger-keepers that run them to block and censor people. A major goal in some alternative systems - such as Monero and Zcash - is to create privacy-preserving currency that cannot be blocked

Targeting particular groups or products: Money is normally experienced as all-purpose: it’s theoretically supposed to be usable by anyone to buy anything from anyone. Some alternative currency designs, however, aim to be ‘limited purpose’, allowing only some people to get certain things from other specific people. For example, the 2020 Tenino Wooden Dollar aimed to allow qualifying welfare recipients to get a limited range of goods from specific stores in a specific town during pandemic times

Modulating, accelerating, decelerating, releasing or constraining ‘free markets’: Crypto libertarians tend to imagine that ‘free markets’ exist in nature, but that they are distorted or blocked by some ‘unnatural’ abomination of nation state politics and fiat money. In this context, they imagine that their tokens will ‘release’ the power of capitalism by bypassing restrictions on free markets or providing some new means to trade. A person who builds a local currency, or a peer-to-peer rippling credit system, by contrast, may be seeking to do the opposite: they may want to constrain the alienation, isolation and exploitation unleashed by global markets

To mediate the human economy and the spirit world: I realise this is a pretty obscure thing to say, but much pre-capitalist ‘money’ (such as shell money) is actually a system of fetish objects designed to mediate power relations between people, the living and the dead, and the natural (spirit) world. This is something that our normal capitalist money systems - with their reductive focus on the movement of commodified goods - really struggle to do.

It’s also important to remember that the people who design or take part in alternative currencies are human beings that will always harbour hidden private goals. The two most important ones to acknowledge are:

To give purpose and community: Many people who get involved in alternative currencies do so because it gives them something exciting to do and friends to do it with, regardless of whether their actions have any actual use for the rest of the world. Taking part can be performative, like volunteering for a theatre play where you get to act out a fantasy. This may sound cynical, but for many people this is something they need. Crypto-token communities, for example, are full of folks posturing about something that they’re doing ‘out there’ in the world, when in reality they’re mostly just talking on Reddit forums and discussing trading strategies, activities that give them a sense of community. Alternative systems - like alternative lifestyles - help to give people who are seeking a sense of purpose some (often illusory) sense that they’re doing something important within an economy that often doesn’t care about your purpose

To make an income: Everyone has to survive in the economy, even if they claim to be building a different one, so being a builder of alternative systems is actually a kind of profession. Our dominant economy creates various markets to support this niche role: there’s a market for messages of hope and change, and a market for collectible monetary novelties, and a market for speculative assets, all of which can be tapped by the prospective alternative currency designer to secure their livelihood. If you’re designing a small local currency this is never going to be lucrative, because you can only tap the first two markets. In the case of mega crypto-currencies, however, the founders can get grotesquely wealthy by selling tokens into speculative asset markets for dollars (albeit they will market those tokens with reference to the other ‘purposes’ above)

Decision 2) What paradigm will you use?

Once you’ve come to terms with what your (true) purpose is, you face the question of what rough paradigm of alternative currency you might use to achieve it. Your choice will be influenced by whether you have a commodity or credit orientation to money (for a detailed exploration of this, see 5D Money, and for a lighter introduction see Money through the eyes of Mowgli). You’ll also need to think about what ‘grafting’ method you’ll use to interface your new currency with our existing system. Here are some options.

Paradigm 1: Voucher and ‘plug-in’ systems

One the the quickest ways to bootstrap an alternative currency is to just plug it directly into our existing monetary system by ‘backing’ it with a national currency. The grafting method here is tried and tested: the alternative currency issuer gets a bank account where they hold Layer 2 bank-issued money (see The Casino-Chip Society), which is partially tethered into Layer 1 central bank money. They then issue ‘Layer 3’ vouchers on top of that, either in digital or physical form.

There are literally tens of thousands of plug-in systems like this, but they vary in scale, branding and use. Here are some examples:

Mega-scale systems like PayPal, and the decentralized equivalents that we call ‘stablecoins’ (see How to build an origami stablecoin)

Company vouchers that ring-fence the use of a broad national currency into a particular store. In digital form these sometimes get called ‘virtual currencies’, which are just digital vouchers for a national currency rebranded with a company name (e.g. Amazon Coin)

Local voucher-based currencies (like the Brixton Pound), which are systems that ring-fence the use of a national currency into a collection of stores found in a particular region, city or neighbourhood

A stronger version of all this is to create your own bank that plugs into the central banking system - like the WIR Bank in Switzerland - and to then use that institution to issue a variant of the national currency

Paradigm 2: Paying-by-promise in the credit commons

We all have the ability to issue promises to each other. If you formalize that process by creating rules for their issuance, and systems to track them, you can actually create a monetary system. This concept of ‘paying by promise’ with IOUs is the foundation for a whole family of alternative ‘credit currencies’, such as mutual credit systems, time-banks, local exchange trading schemes (LETS) and new-wave rippling mesh credit systems. My piece Zero is the Future of Money lays out a framework for thinking about this style of alternative currency.

These are some of the hardest systems to build, but they can also be the most profound, because they’re true attempts to grow semi-autonomous monetary ‘nervous systems’. Unlike the voucher systems above, which just plug into a national currency, these systems are much trickier to graft into people’s lives. Systems like Sardex in Sardinia, for example, operate independently of the mainstream Euro system, but try to partially blend in by importing Euro pricing into their system.

Paradigm 3: Countertradeable (crypto) collectibles

It’s common to hear crypto-token promoters claim they’re going to outcompete the fiat money system, but in reality, systems like Bitcoin are not in direct competition with mainstream currency. Rather, they are limited supply digital collectibles that are sold into normal asset markets, where they will compete with other assets - like shares or artwork - to get bought with normal currency. This allows them to get a speculative dollar price, which in turn furnishes them with a new property, which is the ability to be ‘countertraded’.

Countertrade is the process by which you pay for one thing with something else’s resale price. So, rather than handing over $1000 for a surfboard, you hand over something (or numerous things) that can be resold for $1000. You can pretty much do countertrade with any object in the world, but some are far more countertradeable than others. It just so happens that digital crypto-tokens have very high countertradeability. Furthermore, the fact that these collectibles come branded with monetary imagery means it’s quite easy to engage in the illusion that you can ‘pay’ for things with them, when in reality you’ll pay with their dollar resale price. This is why, if you’re sitting in El Salvador - where Bitcoin is legal tender - a restaurant owner will never tell you what the ‘Bitcoin price’ of your meal will be at the outset, because it fluctuates thousands of times over the course of your meal as the countertrade ratio constantly shifts due to changes in the token’s global dollar price.

This isn’t necessarily a critique, because creating a countertradable collectible is actually quite a savvy way of grafting a new token into our existing monetary system. Nobody can claim that Bitcoin hasn’t been successful, and that it doesn’t create new pathways to trade, even if its exchangeability constantly fluctuates in direct response to its dollar price. That said, while countertradability can be a successful method for getting your token to ride on top of the existing system, inducing it tends to require a marketing strategy that denies it’s taking place. Most crypto-token promoters have to engage in an elaborate masquerade in which they pretend to compete with the very thing their tokens are priced in. This is partly why the scene is so rife with cognitive dissonance, but hey, it kinda works sometimes.

Paradigm 4: Cere-money

There’s a particular bigotry in Western culture in which pre-capitalist ‘money’ - like wampum beads - is seen as crude and primitive. I don’t share this view, because I come from an anthropology background, and I’m deeply influenced by critical anthropologists like David Graeber (see The Anthropologist in an Economist World). Anthropologists are often annoyed with how economists take ceremonial money systems, like the rai stones of Yap, and place them on the bottom of a ladder that leads in a chain of evolution up to modern digital money. In reality, many of these ‘cere-money’ systems still exist to this day, operate on very different principles to normal money, and can do things that mainstream money can’t do.

Here’s the very short version of the story: modern money is associated with the ascendency of capitalist market economies, which tend to be associated with a fixation on commodities detached from humans. Pre-capitalist ‘human economies’, by contrast, tend to carry far less of this ‘commodity fetishism’, in that people recognise that economic value lies in people, not things. Human economies like this are associated with ‘social currencies’, ceremonial objects that act to mediate human relations, unblock tensions, facilitate unions and placate or activate the spirit world.

If you’re interested in those latter things, you might consider creating your own cere-money system. Many of these tend to operate with a ‘syncretic’ logic nowadays, with one part that exists in a parallel reality to normal money, and another part that’s integrated via countertrade dynamics (see section above). If you want an example of this, check out my profile of modern Tabu shell money of Papua New Guinea.

Paradigm 5: ‘UBI’ currencies

A ‘universal basic income’ (UBI) is a welfare system in which normal currency is sucked out of circulation through taxation and then blasted back out to everyone in equal amounts. There are various reasons why you might want to do this, and various political takes on it, but - since the crypto boom - there’s also been a whole range of people interested in ‘UBI currencies’: alternative currencies that claim to embed some kind of UBI into their operations.

I write ‘UBI currencies’ in quotes for two reasons. Firstly, for something to be an ‘income’, it first has to actually operate as money, and many so-called UBI currencies don’t. Secondly, it’s questionable whether ‘UBI currencies’ count as a category in themselves, because often these projects are just people experimenting with a distribution model for tokens, rather than asking what those tokens are and whether they’ll actually operate as a meaningful income to people.

A classic example of this is Worldcoin, which uses biometric eye recognition to identify people as unique, so that those people can be granted their ‘basic income’ in the form of a dubious token. Worldcoin was founded by OpenAI founder Sam Altman. People like Altman are scared of rendering everyone unemployed through the automation tech they’re pioneering, so they’re keen to experiment with pushing out tokens that might keep markets alive as people are deprived of incomes from work. Other systems, like GoodDollar, collect donations, invest those in ‘DeFi’ markets, and then redistribute the proceeds to people who sign up. Systems like Duniter use Einstein’s theory of relativity applied to money, in order to work out a theoretical daily distribution of tokens for everyone on the system.

Decision 3) What parameters will you tinker with?

Once you know your purpose and paradigm, you can start to fine-tune it. I’m only going to touch on some of the different elements here, because this is where a lot of the technicalities come in, and I’ll have to expand on those in future pieces. Here are some specific questions you want to start asking.

Precisely what are your alternative currency tokens?

What activates your token?

What form are they released in?

If the unit is digital, how will it be tracked and who controls the database?

Are the units all-purpose, or limited-purpose?

What’s your ‘monetary policy’?

Let’s go into each of these in turn.

Precisely what are your alternative currency tokens?

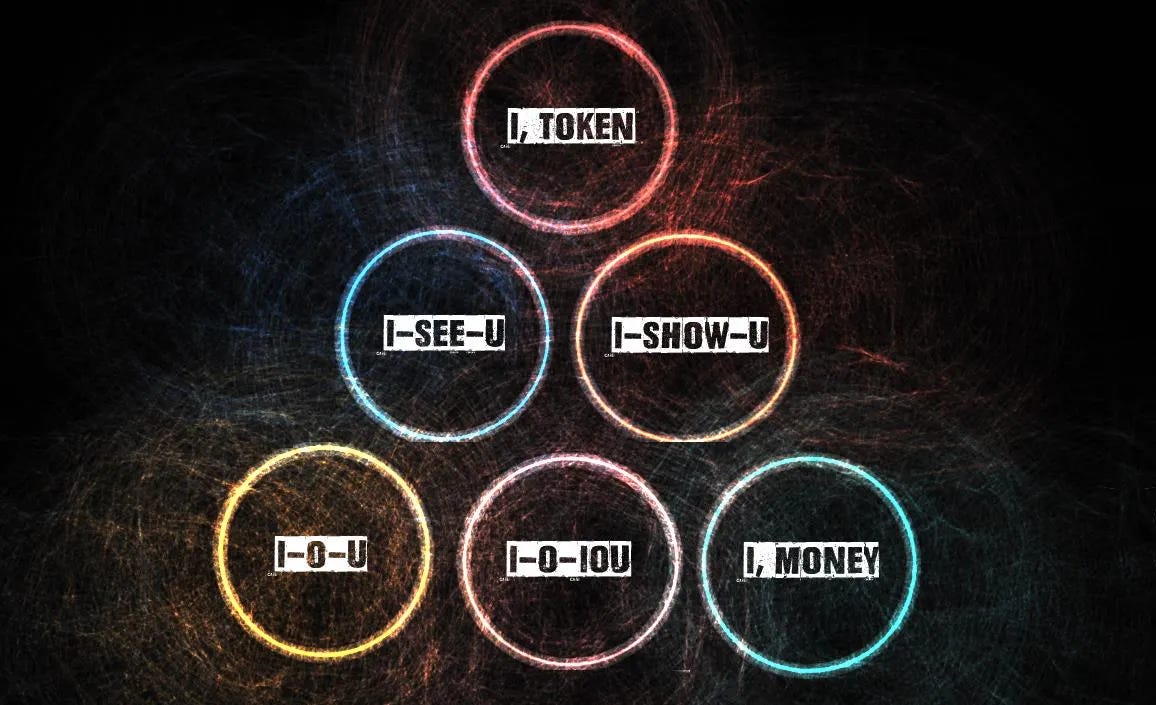

There’s more to creating a currency than just releasing numbered tokens. You really need to know what exactly your tokens are, so you can build a strategy for how you will ‘activate’ them into a monetary system. I go into detail on some classic token types in my piece the Six Tokens, but here are a few options:

Blank tokens: these are the most primitive type of token you can release. In physical form this is just a blank object, but in digital form they’re just written-out numbers (or more specifically, numerical nouns - see I, Token). Many old-school crypto-currencies are just blank tokens, but in crypto-land energy may be required before you can write them into existence

Badges: these are objects handed out in recognition that you did something. They generally make for kinda crap monetary systems, but many people do try use them as the basis for a currency. The original version of Eco coin, for example, was just a badge handed out to people who did positive environmental actions, albeit the newer version is incorporating elements of access tokens (see below)

Access tokens, vouchers and IOUs: all of these are objects that explicitly give their holder the right to access something beyond the token. They tend to go hand-in-hand with the voucher and IOU systems discussed in section 2 above, but it’s worth noting that normal money uses an inverse version of these as its raw material (for example, state money gives you access to freedom from tax obligations)

Ritualistic objects: if you’re interested in creating a cere-money system, you’re going to have to charge-up some objects with cultural power. This is an ancient art-form, and you’ll probably need to delve into the anthropological archives to uncover it

What activates your token?

All token types need to be activated to have any power in the world. People have various takes on how this is supposed to work. Here are some possibilities:

Guaranteeing redeemability: All access tokens, vouchers and IOUs primarily work through an issuer guaranteeing to redeem them for something. In the case of mainstream money systems, these guarantees are legally-enforced

Claiming the token has ‘intrinsic value’: people with a commodity orientation to money will tend to claim that a money unit has (or should have) some kind of ‘self-apparent’ value that resides in the token, such that everyone will naturally see that it’s valuable and want to trade it. It’s a dubious theory, and it almost never applies to alternative currency

Seeking to induce ‘fictitious’ value: a common variant of the commodity orientation to money is to imagine that a unit without ‘intrinsic value’ can be turned into a fictitious substance of value through some act of communal belief. This is the source of statements like ‘money is what we say it is’ or ‘money is money if we believe it is’. You’ll often encounter this in crypto communities, where the designers claim that an otherwise blank token will be given value by the fact that people use it or believe in it. In the case of cere-money systems, there actually is some validity to this belief, but it’s a pretty weak theory outside of that context

Creating speculative hype to induce monetary price and countertradability: most crypto tokens actually rely on people perceiving them as speculative objects to be traded on a fiat market, because it’s the resultant monetary price that will in turn induce countertradability in them (see above), which is actually what activates their power to command goods from people in the economy

Locking the token into a state of network interdependence: libertarians often imagine that mainstream money is backed by ‘government coercion’, but that’s only the most visible form of coercion in our system. In a situation of true large-scale interdependence, your very survival depends on getting access to the labour of others, and if money is the only way to do that, it’s your interdependence that will ‘coerce’ you towards using the units. This ‘network coercion’ is actually very difficult to induce in an alternative currency system, because by default the alternative currency isn’t going to be the basis of your survival, but it’s one thing to aim for

I go deeper into a lot of this in my 5D Money series, but it’s important to realise that there isn’t necessarily a single means via which tokens get activated. Indeed, money has different logics that intersect on different planes.

What form are the units released in?

Once you know what you tokens are, and how you plan to activate them into a money-like system, you face a choice of what form to release them in. The major choice is physical versus digital. There are affordances to physical that differ from all forms of digital (which is one reason why I spend a lot of time defending the mainstream physical cash system), but you could also offer a combination of forms.

If the unit is digital, how will it be tracked & who controls the database?

Digital units always rely on a database to track who holds them, but you face a question on how you’d like to implement that database. Will it be a traditional centralized database, under the control of an administrator, or will it be a decentralized one held in play by a network of distributed nodes? The latter is the primary innovation of the crypto world. Bitcoin, for example, is a decentralized system for moving blank tokens around, which is what enables them to become countertradable collectibles. Sardex, by contrast, is a small but centralized digital system for keeping track of IOUs issued by a local network of SMEs.

Are the units all-purpose and range, or limited-purpose and range?

Theoretically, money acts to reduce everything to one thing: thousands of diverse objects stemming from tens of thousands of diverse people’s labour are all rendered in a common form - a price tag - theoretically enabling anyone to hand over money units to get anything from anyone else. Some alternative currencies - like Bitcoin - seek to replicate this ‘all purpose’ quality, but others will seek to put limits on the use and range of the currency. Any attempt to limit people’s spending comes with politics, but here are the main parameters to mess with:

Geographic range: most mainstream currencies have geographic limits, because they co-exist with nation states. This means they have to use elaborate international payment structures to co-ordinate ‘hops’ across national boundaries. Systems like the Euro attempt to transcend national boundaries, but many local currencies attempt to reduce the scale of a national currency down to a city or neighbourhood level. Tinkering with the scale of your system, and how it interfaces with larger-scale systems, is a major element of alternative currency design. The basic rule of thumb is this: the larger the scale of your system, the more stuff will be available within it, but the more alienated each user will be, as the scale of the system dwarfs them (and may disguise exploitation). The smaller the scale of your system, the less stuff there will be within it, but the more connection each user may experience with the others. Put differently, large-scale systems ‘dissolve’ communities into large formless bodies of people who just see themselves as floating ‘consumers’, while small-scale systems connect people into more holistic closely-knit meshes

Redeemability limits: a local currency tinkers with geographic range by limiting the redeemability of the unit to some local area, but you can also introduce redeemability conditions to a currency in order to promote particular products over others, or block particular products. This kind of conditionality - which in the digital realm gets called ‘programmability’ - can have paternalistic overtones, but it might be employed, for example, by an intentional community who wants a ‘green currency’ that can only be used for organic products

Time limits: just like certain coupons and vouchers have a time-limit after which they expire, an alternative currency can have time limits that seek to encourage circulation. Historical systems like the Wörgl stamp scrip system in Austria used in-built ‘demurrage’ to erode the unit over time, in order to speed up its circulation during the Great Depression. The resultant ‘Miracle of Wörgl’ has even been turned into a feature film, which you can watch on YouTube.

Finally, what’s your ‘monetary policy’?

When you hear monetary policy wonks speaking, they’re not normally discussing all the stuff above. They don’t care about tinkering with the nature of monetary tokens, or shifting their redeemability, but they do care about altering the supply of units, the speed of their circulation, and their ‘value’ (aka. power).

In Zero is the Future of Money, I noted that there are at least four different zones of dynamism in our mainstream monetary system:

The increases (issuance) and decreases (redemption) in the (3-layered) money supply

The increases or decreases in the velocity with which transfers between money users take place

The surges (booms) or contractions (busts) in the underlying production in the economy

The increases and decreases in the power of the monetary units to command people to produce things or give you stuff (commonly called ‘deflation’ and ‘inflation’)

Even in a small alternative currency system you have to be aware of these dynamics. One of the classic problems in a small-scale time-bank, for example, is that there are frequent ‘recessions’ where people who have accumulated positive credits hoard them and thereby prevent others who want to have their labour employed from being able to work. Figuring out your ‘monetary policy’ in this situation is a very intriguing challenge.

In fact, all the systems we’ve covered above have different scopes to mess with the token supply, circulation speed and power. Some systems, like algorithmic stablecoins, have elaborate mechanisms to peg their units to the power of major national currencies, which means they end up importing much of their monetary policy from those systems. A system like Bitcoin, by contrast, has a robotic production process for its tokens, so the ‘issuance’ part of the equation is hard-coded, which severely limits any attempts to have a dynamic ‘monetary policy’. This doesn’t actually matter for Bitcoin, because it’s not strictly intended to be a pure money system: as mentioned, regardless of the rhetoric that surrounds it, it actually operates as a countradable collectible, and to do that it needs its tokens to be perceived as limited edition digital medallions, rather than the dynamic money that would appear on a price tag stuck to those medallions.

Decision 4) Who are your participants, and what are their roles?

Our normal monetary system has a set range of participants. On the one hand there are issuers - like central banks, treasuries, commercial banks, PayPal etc - but some of them might contract manufacturers like mints and banknote companies to produce the physical version of their tokens that they will later issue out. Then there are users, like us, who are on the receiving end of that issuance.

Your desired participants could be really diverse or really specific. Maybe you want to create a regional currency to connect together rugged ranchers with urban hippies who want organic meats. Perhaps you want a cere-money system to help war veterans release grief, guilt and trauma. Perhaps you want a speculative crypto-token that you can sell to raise dollars to build an anarcho-capitalist seasteading community, while claiming that the tokens will later give the holders access to an ocean-based economy.

Regardless of who you want to be involved, it’s important from the outset to give your participants clear and non-contradictory roles. To do this you need to be clear on the difference between manufacturing a token, issuing it as an issuer, and receiving it as a user. For example, a printing company may manufacture a voucher for a luxury eco-village spa, but it’s the spa that will take that and issue it to its customers, who will experience themselves as users of that voucher.

To be an issuer of currency is like being the issuer of a promise: it initially emanates away from you, rather than coming towards you. I’ve seen crypto UBI systems like Duniter, for example, claims that its participants collectively ‘issue’ their own currency, when in reality the participants are just granted units manufactured by a digital protocol, and their only role is to then transfer those units between themselves. Systems like Bitcoin also have no true issuers in the traditional sense of the word: rather, they have miners that essentially manufacture the tokens, after which they can transfer them, or keep them. In a mutual credit system, though, you do get true issuance, and it happens when people go below zero in the system.

Don’t know which path to take? Try a randomizer

I go deeper into all of these paths in my Unboxing Alternative Currency and 5D Money series, but I hope this has given you a taster of some possibilities. I’d love it if let me know in the comments what choose-your-own-adventure path you’d take.

If you’re struggling to know which route to go down, it can be fun to randomize it. Assign numbers to the various options for the various decisions above, and then go to Random.org to generate numbers to guide you in your decisions.

Maybe you’ll end up with something potentially doable, like a localist IOU system with physical access tokens with redeemability and time limits. Maybe you’ll get something unhinged, like a UBI currency based on ritualistic objects powered by speculative asset markets. You’re probably not going to solve the mass pollution of our oceans with either of those, but no matter what path you go down, keep in mind the big picture: money is the nervous system of the global economy, and unless you’re under the impression that our system is an exemplar of balance and transcendence, there’s no harm in attempting to alter its consciousness.

If you’ve found this useful, please give it a like, leave a comment, and consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Cheers! Brett

"... To replace it (the money system) you’d actually have to re-grow our entire economic organism, ....Anybody that’s imagining a wholesale replacement of one monetary system for another, and is not expecting the body to die in the process, is… well... delusional."

This is an assumption not a fact. First what do you mean by "wholesale replacement"? If you are suffering from scurvy several vital systems (connective, circulatory, immune, etc..) cease to function, do you replace them or do you correct them by adding enough of one of the simplest molecules (C6H8O6 aka Vitamin C) known to biochemistry? If you do add vitamin C, a "wholesale replacement" has taken place, i.e. from dysfunctional system A to functional system B. But notice that little was done to achieve such a colossal transformation.

The take home is to know how to define a system, removing one detail completely transforms a system from a functional <=> dysfunctional, stable <=> unstable, passive <=> active. In the case of money systems mainstream or alternative, we need to first determine the problem statement they are to address and only then can we talk about what requirements need to be satisfied e.g. do we need to produce alternatives or will a simple correction of what is already in place be sufficient?

Finally, you need to understand how systems affect other systems they come into contact with, e.g. any passive system cannot coexist in conjunction with an active system unless it is completely isolated and independent.

http://bibocurrency.com/index.php/downloads-2/19-english-root/learn/300-you-have-been-served

Maybe your starting point as to the ‘Altered State Of Monetary Consciousness’ begins with your anthropological awareness that “Pre-capitalist ‘human economies’, by contrast, tend to carry far less of this ‘commodity fetishism’, in that people recognise that economic value lies in people, not things. Human economies like this are associated with ‘social currencies’, ceremonial objects that act to mediate human relations, unblock tensions, facilitate unions..” These social orders did not suffer from the reductionist delusion of the separation of the individual from the group. And their credit systems were WAY MORE than ceremonial objects……and those social credits themselves provided the tools to “mediate human relations, unblock tensions, facilitate unions.”

What is interesting about this “Altered State” is that the MSTA finds this moment of the mistaken notions involved with ‘commodity fetishism’ as the place to which we must focus our attentions. Because correction of this takes us to simple bookkeeping about the activities within these ‘human economies’ and delivers us away from the illiterate consequences of this commodity fetishism you so cogently point to.

You see, if the focus is on this foolish ‘commodity fetish’ and the misguided attempts to use the features of commodities as if they legitimately apply to abstract unit based representation of a ‘human economy’ (and in the end there is no other kind), then the “nervous system" analogy you give to money (which I interpret to mean an information system) can only become a “contributor to any emergent ‘consciousness’ that develops in and around that system” if it first starts with bad information (money has the features of commodities) and then operates in feedback loops related to this.

You wrote: “Money is the nervous system of the global economy, and - like any nervous system - it’s a core contributor to any emergent ‘consciousness’ that develops in and around that system. So, if you feel that maybe the global economy is like a numb, delusional and paranoid wreck walking towards oblivion, it makes sense to consider how we might alter the state of its nervous system.”

Is the economy that way because the ‘consciousness’ about money is delusional and causing the numbness and paranoia? Focus on the feelings is not enough if those feelings are rooted in delusion or the mistaken. The ‘emergent consciousness’, if based in delusion will be unaware of the root of the paranoia, because that is the problem with delusion. But the human perception at some basic level (those same feelings) has the awareness of the impossibility of being able to make the present system work. And this becomes a feedback loop within this nervous system/communication system/information system/the present money system that surely and realistically does feel like “walking towards oblivion.” So, this state of affairs must deeply look into the dynamics of this ‘emergent consciousness’ you point at.

It seems to me that WAY Too Many of the ‘solutions’ in so called ‘modern’ economic models are nothing more than circling attempts to make the misrepresentation of money (commodity features can be legitimately applied to the abstract unit used to represent the interchange of economic value) work.

When a populace has only one frame of reference, and that one is invalid, it cannot even begin to know what is wrong. The point about not having any other frame of reference is critically important, because there is no guarantee that the 'development' of humanity has gotten stuff figured out correctly. Which raises the question: What do we have wrong?

One of those things that we surely have wrong is money. And we have had this wrong since the time we switched from fungible commodities as trade goods to abstract unit based representations of value interchange used in bookkeeping. What we got wrong is that, because we "conflated the two mutually exclusive notions of “measure” and “commodity” - be it either conflating “measure” with (fungible) commodities such as gold or silver or “commodity" with mere annotations of value such as fiat notes" (Marc Gauvin) - we assigned the properties of a commodity to a simple abstract unit! In doing this we messed up our own abilities to have stability in our acCounts and bookkeeping and society as we sought to 'own and protect' the abstract units as though they were fungible commodities, when they were/are but abstract representations of the value contained in the stuff of real value in our interchange!

Through all this time in human history, since before the formation of Nation States, we have been confused about what Liberation through bookkeeping and abstract representation of our own interaction needs in order to work. Because the goods interchanged no longer need an intermediate fungible trade good. What we need is a specification for a 'unit of value' with which to measure/annotate and keep the records about the value contained in those items of genuine value about which we are writing stuff down! Please take a look at this paper. http://www.bibocurrency.com/index.php/downloads-2/19-english-root/learn/271-brief-history-of-money-s-misrepresentation

I celebrate your willingness to challenge the status quo and to ask what we have been getting wrong.

It seems to me, that with regard to money, we are still in a 'pre-Copernican' era thinking that fungible commodity-like money is at the center of our economic world when it cannot possibly be. And so long as we subjugate ourselves to the foolish need to have money retain the attributes of fungible commodities we abandon our own position as the initiator (the center) of economic capacity and give ourselves over to the eventuality of control exhibited by those strong armed protectorates that have developed into the Nation States along with all the corruption that entails.

There is a way out that involves simple monetary literacy. Check this out!!

http://www.bibocurrency.com/index.php/downloads-2/19-english-root/learn/300-you-have-been-served