Imagine you are an inter-stellar adventurer who crash-lands on a distant planet. You are rescued from your wrecked spacecraft by members of an alien tribe, and they give you shelter in their village. You don’t speak their language, but over time seek to earn their affection by drawing sketches illustrating your existence on Earth. Their children giggle as you sketch various aspects of your life, such as your house, and the city you live in, but you eventually arrive at money. You notice they are hunter-gatherers who have never used it, so what images will you use?

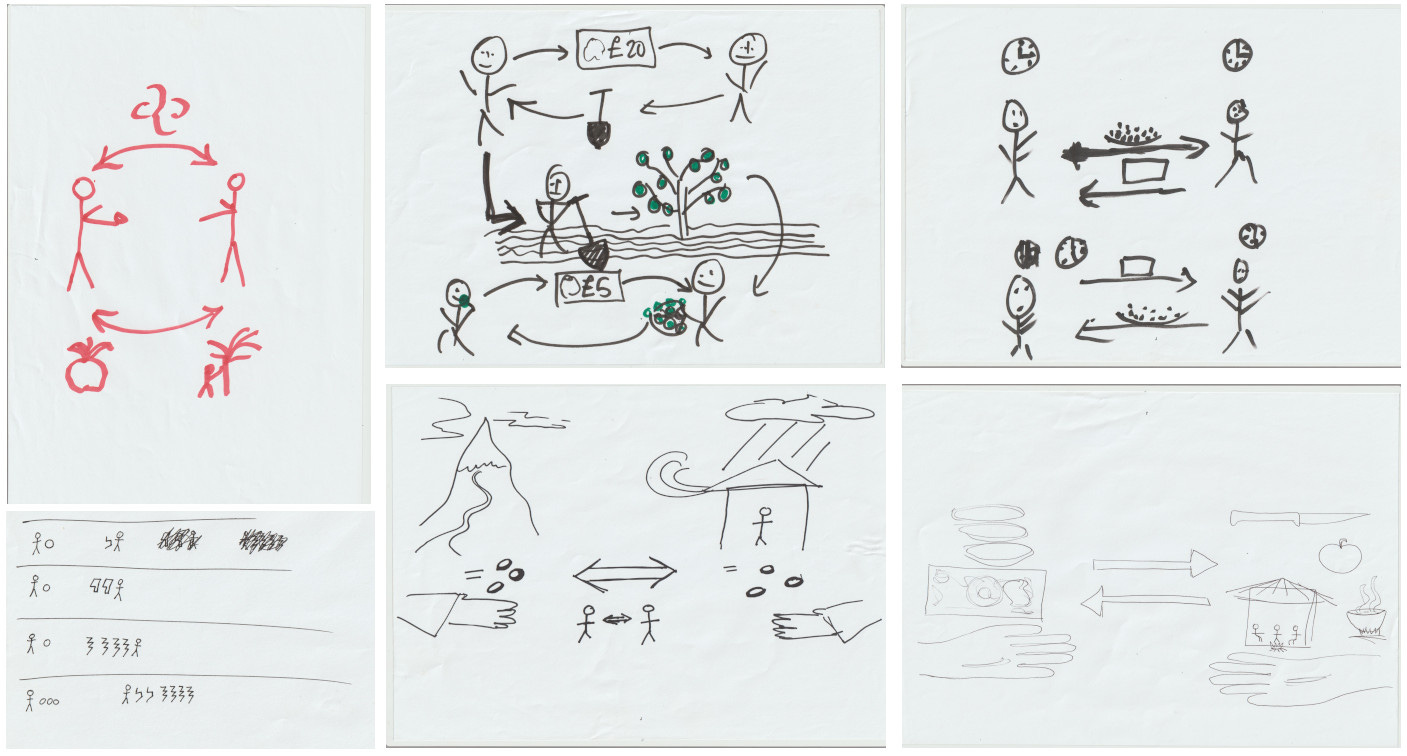

I pose this as a thought experiment when I run money workshops. I give students a sheet of paper and ask them to draw out the concept of ‘money’ for a person with no experience of it. They often converge on similar scenes. The most common is to draw someone holding fruits, with arrows pointing to another person holding notes adorned with abstract symbols. Here are some examples I’ve collected.

The second most common approach is to simply draw goods adjacent to money units, as if to hint at the idea of money being a malleable substance that can stand in for things like apples or houses. Here is a collection of examples.

When you combine these two approaches together, a general impression arises. It seems that the students are trying to hint at an economy made up of individuals who come together to trade, with one handing over goods (well, mostly fruits) in response to another that hands over money, which appears to be a special class of good that can be moulded into the likeness of the others by changing its quantity.

In my last piece – Money through the eyes of Mowgli – I explored the mental scaffolding that underpins the ‘commodity orientation to money’, and we see this orientation playing out in these images.

In the article I noted that the commodity orientation is not a literal belief that money is a commodity, but rather a tendency to approach money - regardless of its form - as if it were a commodity. This tendency goes hand-in-hand with a particular viewpoint on the economy, which I referred to as the Tarzan Suite: you visualise an economy as starting with solo individuals, who use inner reserves of energy to produce stuff that they subsequently have the option, but not requirement, to trade. With this mental backdrop in place, you will imagine barter, in which one solo person approaches another, and dangles something of value in front of them in order to override the other’s desire to hold onto the thing they’ve produced. When this mentality is superimposed over money, you begin to imagine money as a universal commodity with value, which can be exchanged for more specific things with value. This culminates in substance imagery, in which money is imagined to ‘carry value’ and to ‘flow’ (as if it were like blood pumped by individuals around an economy).

I also suggested there are two versions of this substance-of-value view: in one, money is assumed to be a literal useful substance. In another, it is assumed to be a ‘fictitious substance’, created through imagination or social agreement. Regardless of what version a person uses, this phenomenon of seeing money as a substance-of-value coexists with imagery of mutual contract – the point where two solo individuals approach each other and hand over ‘value’ to each other before backing away. Notice the mutual contract imagery in the first set of drawings above. They are framed in terms of voluntary interaction between individuals, rather than non-voluntary interdependence. The pictures are not intended to represent inescapable collective entanglement, and that’s the problem.

Would the aliens understand?

While these images seem to make sense to the people drawing them, they almost certainly would not make sense to our hunter-gatherer aliens. Why not? For a start, they would misinterpret the nature of the relationship between the pairs of people in the imagery.

In the drawing above, for example, the pair is supposed to represent solo individuals (who do not know each other very well) meeting each other in ‘the economy’, but for a hunter-gatherer the economy is a small and tightly-woven band of interdependent people who are inextricably bound to each other. In this context, any pair of people will be assumed to be close kin, locked within multi-dimensional relationships with each other and with all others around them. They certainly would not be assumed to be strangers meeting on a market (whose relationship would cease after the trade ended). In a hunter-gatherer community there is no such thing as a pure exchange stripped of other relationships, so these drawings of individuals with arrows between them would fail to convey the idea of ‘trading’. If anything, hunter-gatherers would interpret the arrows as referring to an ongoing cycle of reciprocity that preceded the two individuals, and that never ends.

It helps to have some background in anthropology to notice these kind of nuances. In my Anthropologist in an Economist World (a piece dedicated to the late David Graeber), I noted that I come from an anthropology background, and that economic anthropology has a lot of disagreements with mainstream economics. Primary among these disagreements is that anthropologists typically do not assume that trade is the default mode of economic interaction between people, whereas economists often do. This is because anthropologists historically have spent a lot of time among groups that are not completely absorbed into capitalist markets, and who maintain pre-capitalist ways of being (this includes hunter-gatherer groups, horticultural and pastoral tribes, and groups with feudal and caste structures).

It is easy, however, to make the mistake of believing that ‘pre-capitalist’ means cooperative, and that anthropologists spend their time romantically showcasing the harmonious cooperation of hunter-gatherer societies as a contrast to the capitalist competition that economics focuses on. The true distinction between economic anthropology and economics is far more subtle than that. The anthropological record is full of examples of competitive power plays between tribal people, but this competition is seen as being set within the bounds of inescapable interdependence. No Big Man in any tribal society is operating under the delusion that they can exist apart from the rest. The pre-capitalist mentality is one in which everyone is far more aware that they are social animals dependent upon others, and it is only within that field that they can then begin to wrestle with how to reconcile their individual drives with their communal reality.

Economics, by contrast, starts by downplaying the communal reality, and by imagining that the starting point of society is individuals making rational choices. Economists do not deny that cooperation exists, but they do present it as being a kind of ‘choice’ made by free-floating individuals, who could also choose to compete (the field of game theory, for example, is predicated on this idea that group cooperation is founded upon a substrate of individual choice). The key thing that distinguishes economics then, is not that it focuses on competition (indeed, the boundary between cooperation and competition in markets is actually quite thin, because any exchange is technically an act of cooperation, even when it has competitive elements). What really distinguishes economic thinking is that it operates under the assumption of separation between people, which is why it then romantically fixates upon things like mutual contract, which is that moment when the separation between individuals is imagined to be briefly bridged.

This fixation upon temporary bridges between solo people drives our standard accounts of monetary history. In my How to Write a Flintstones History of Money, for example, I showed how the economics discipline projects this assumption back in time in order to generate the mythology of barter as the origin of money. Ironically, what economists end up doing is taking a mentality that was peripheral in ancient society and imagining that it was central. Anthropologists do not argue that barter-like transactions never happened in ancient societies, but they do recognise that it mostly occurs on the outskirts of such social groups, where social ties get weaker.

For example, internal to indigenous Nepalese tribal groups there is little trade, but externally they have some forms of stylised exchange with other groups. They may leave honey on the edge of the forest, and wait to see if distant villagers will leave something in exchange for it, but these limited cases of peripheral barter were not the central driving force of pre-capitalist economies. It’s only when you are immersed in a society in which market transactions are central - which really only occurred in the last couple hundred years - that you may generate presentist fantasies about an ancient world in which a cruder version of that reality existed, and where everyone was wandering around like Tarzans bartering with each other.

The moral of the story, though, is that if you present an image of two people facing each other to hunter-gatherer aliens, they will not assume that a temporary act of trade is occuring. Their default assumption will be that the people have a permanent bridge between themselves, held in place by elaborate systems of reciprocal gift-giving that take place over time, and which entangle them in social ties. The idea that the people are free from social ties, and that they require each other to dangle a commodity in front of each other to induce the formation of a temporary barter-like bridge, would be… well… alien to our aliens.

The substance-of-value fetish

But let’s for a moment imagine that you succeed in convincing the aliens that two individuals from two different bands have met on the boundaries between their territories, and are now trying to engage in a barter-like interaction. Even if our aliens grasp this idea, what will they make of the fact that one person is handing over goods while the other appears to hand over some small symbolic object? Living as hunter-gatherers they would understand the value of pieces of fruit, by why give up the fruit for an abstract rectangle? Is it a holy artwork, or a magical talisman?

In many of the pictures shown the money does actually appear like a magical talisman. All kids grow up seeing mummy and daddy hand over money at a store while goods come back the other direction. At a surface level there is in something quasi-magical about that, and kids will sketch monetary exchange in much the same way that adults do – as if it were somehow contained in a little bi-directional bubble, in which a magical object seems to equate to, and command, goods.

One of the most complex points to convey about this is that modern large-scale monetary systems generate this commodity mythology. This is because – regardless of what the true nature of our money actually is – our monetary systems catalyse large-scale economic networks, which get so big that we lose sight of all the people who we are dependent upon. From this point we can begin to indulge in the fantasy that we are separate from them, which leads to us imagining that exchange is the process by which solo individuals build temporary value-bridges between each other. From this vantage point, it will begin to superficially appear like the money in your hand has some kind of one-for-one relationship to goods that come back over the bridge when you hand it over. You begin to say things like ‘people hand over goods of value, because the money has value’.

This creates cognitive dissonance, because the money clearly isn’t a commodity, which is why many people have to resort to fictitious substance explanations, where they try argue that the ‘value’ money carries is created through our imagination, or through social agreement.

This will appear bizarre to our aliens, because they will have a very strong understanding of what value actually is. Hunter-gatherers survive by using their labour to get things from the land. Without land, labouring will do nothing. Without labour, nothing on the land will accrue to them. Furthermore, labour is not individual - each person who labours cannot exist apart from the others. For hunter-gatherers then, economic value is synonymous with other people and the environment. If you had to tell them that actually this value has somehow been transported into little pieces of paper (in an act of imagination), and can now be passed around by moving those, they would tell you that you are crazy. This is why those images of abstract units equating to fruits would fail to have any meaning.

For a hunter-gatherer, being able to access future value from the land and people is dependent upon all the ties of reciprocity that weave them together, which – in a sense – operate like a distributed ‘bank’ of future claims upon everyone else. They know that their survival resides in having a continual link to other people, rather than in trying to grab objects produced by other people and then backing away. Put differently, hunter-gatherer societies have far lower levels of alienation and commodity fetishism, the Marxist term referring to the quasi-mystical belief that somehow objects in an economy exist apart from those that create them.

In many ways, the commodity orientation to money is a special case of commodity fetishism, in which the value that resides in other people and the earth is imagined to magically reside in money. This obscures the location of value in an economy, because you imagine that it is has somehow been ‘captured’ in money, which ‘flows’ around the economy like a vast ‘value transfer’ system transporting a fictitious substance around. This is the same belief that goes hand-in-hand with the delusion that we have some form of solo autonomy, and that we only make temporary bilateral relationships with others, rather than being permanently locked into an interdependent network.

How to start illustrating money for the aliens

Having laid out this critique, let’s mine it for possible clues about how we might actually illustrate money for the aliens. Warning: the content below gets a pretty mind-bending, and it probably needs more editing and clarifying, but I’ll be producing simpler versions in due course!

Consider this sentence that I wrote above:

For a hunter-gatherer, being able to access future value from the land and people is dependent upon all the ties of reciprocity that weave them together, which – in a sense – operate like a distributed ‘bank’ of future claims upon everyone else.

To illustrate money to the aliens, we will have to work with what they already know. One of the keys will be in showing them that the relationships of reciprocity that exist internally to their community would - under a monetary system - be displaced by far more distant ties to a far bigger interdependent network. We would need to show them that monetary systems alter the nature of interdependence: money is the thing that transforms your small-scale interdependence into large-scale interdependence.

The problem, as I’ve already alluded to, is that large-scale interdependence generates the illusion of independence. People are nodes in the same vast network, but are not conscious of the connections, so operate under the illusion of separation, which generates the mutual contract imagery we need to escape from. To do that we will need some form of interconnected network imagery.

But we face a contradiction. Any single person in a modern economy will not last more than a couple weeks without getting things from other people (all the stuff you get in a supermarket comes from distant people), so in principle should understand that they are totally dependent on others. And yet, when they approach another person in an economy they experience each other as separated, and independent of each other. The individual-to-individual experience does not map onto the individual-to-group reality.

This returns me to a key point from my Money through the eyes of Mowgli article. A commodity viewpoint is one in which you imagine that you have an inner ‘battery’ of energy that you use to generate commodities that you then exchange, and which in turn can be used to recharge your inner battery. The alternative (and far more accurate) mentality is to recognise that you have an external battery of energy in the form of other people that you are permanently connected to, and that you must draw upon them before you can get the energy to form part of a battery for others.

In reality, these two perspectives co-exist. Our inner energy forms part of someone else’s external energy, and likewise, someone else’s inner energy forms part of our external energy. But while hunter-gatherers can literally see that others form their external energy, we often fail to see this. And, while hunter-gatherers tie themselves to that battery through elaborate reciprocal gift systems, we rely upon monetary units that superficially resemble commodities. Much like reciprocal ties represent a claim upon future value in a small-scale network, money units act as claims upon the future value immanent in a large-scale network.

To start drawing this, we would need a few elements. Firstly we need an image of a person with a permanent umbilical connection to a much larger network. Secondly, we need some way of showing that only a small and shifting sub-set of that network will act as their external battery at any particular point (unlike hunter-gatherers, the people who we are dependent upon fluctuate from day-to-day). The actual value that flows from these people, through this umbilical connection, will be real goods and services, but monetary systems will unblock or activate that flow. Key to generating this image will be to picture the interdependent network creating a type of internal ‘gravity’ that transcends each individual member, because every member has a requirement to maintain a permanent and non-optional bridge to others, with each person’s external ‘battery’ being made up of others who themselves are dependent upon accessing an external battery.

Ok, I know that sounds heavy, but it could help to picture this in an actual commercial scenario. Imagine yourself in a small shop. We are used to perceiving the act of handing over money as a temporary barter-like act, but cast your mind beyond this. Rather than seeing a monetary transaction as being the exchange of one thing of value for another, it is far more illuminating to picture a money unit as working with the overall internal gravity of a vast interdependent network, to create something like a suction that opens up the unbilical connection between you and one part of your external battery (this person facing you in the shop), and pulls value through. Try picture that the next time you hand over money.

This is turn opens up the meta-question of what kind of unit is best suited for this ‘unblocking’. This is where the imagery can get even more trippy, and where it can intersect with chartalist theories about the role of the state. Much like our external power source consists of other people, the external power source (or battery, if you will) for a state is all the people within its boundaries. The state wires itself to that external power source via money issuance: the units we use for money nowadays are state IOUs (alongside bank IOUs that are built on top of that), issued out by state institutions to get real resources, and anchored by a universal obligation, common across all people, to return the units via taxation systems. Given that everyone forms part of the state’s external power source, the unit designed to connect us to it is perhaps the strongest unit to mediate the multiplicity of smaller-scale connections between ourselves.

There is also a strong argument for state money systems having created this situation of large-scale interdependence between ourselves. In my Subscriber series, I often talk about the horizontal vs. vertical planes of money, which is a way of talking about how powerful ‘vertical’ money issuers can catalyse ‘horizontal’ interdependent networks of ordinary people. This leads to a vision of monetary systems as having an internal gravity within the horizontal interdependent network that can be catalysed, manipulated or altered by the vertical issuers. This all gets very interesting when we start to apply this style of thinking to monetary policy. You can begin to see concepts like inflation and deflation as alterations to the internal gravity, and you can begin to glimpse how money issuance can unlock latent potential in an interdependent network, wanting to get out.

It seems likely that we might need more than one picture to illustrate this to alien hunter-gatherers. I’ll work on those. Perhaps, however, it is best to not show these beyond the boundaries of earth, lest we open the Pandora’s Box of money on a planet free from it.

This is an amazing article, Brett

Can you tell me more about these “Money Workshops” and how I could run one locally? 🧐

So one could first draw the picture of the "external battery" from a single alien tribe members point of view, it consists of the other people of the tribe that he is in relationship with. Now extend that picture by swapping out each of those individuals with a whole set of people, who could potentially fill that role in any given instance. While explaining that we are in a tribe so big that there are so many people for that role, that you don't know them but still they have some way of authenticating to you that they are capable of filling that role, while you use your money to authenticate to them that you are allowed to receive what they provide. In addition the money, now in the hands of that guy, authenticates that he did good to the global community and therefore is entitled to receive from others. So the first picture would be money as authentication.

Another picture that your article suggests is money as external battery (or as a display for the external battery only?): The change of money documents the flow of energy that took place, when you used that guy as your external battery. I.e. that you charged your internal battery using that guy's internal battery. Thereby your external battery decreased but this other guys external battery charged.