How to Make an Origami Stablecoin

Looking for a craft project? Issue your own beautiful moneyvoucher

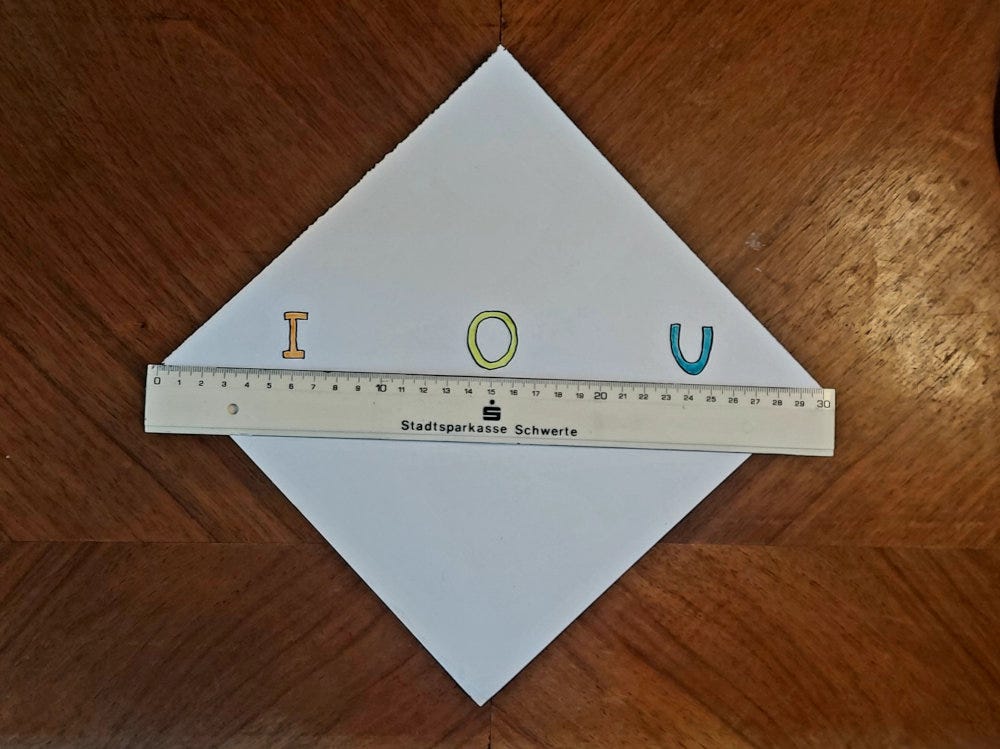

To make an origami stablecoin you’ll need a bank account, a square of paper and a pen. I’ll discuss the global politics of issuing these a bit later, but before you can issue one you must first produce it, so lay the square of paper out and mark it as follows.

IOU is short for ‘I Owe You’. We write this on the paper because a basic stablecoin is a voucher or promissory note (in common language, a promise).

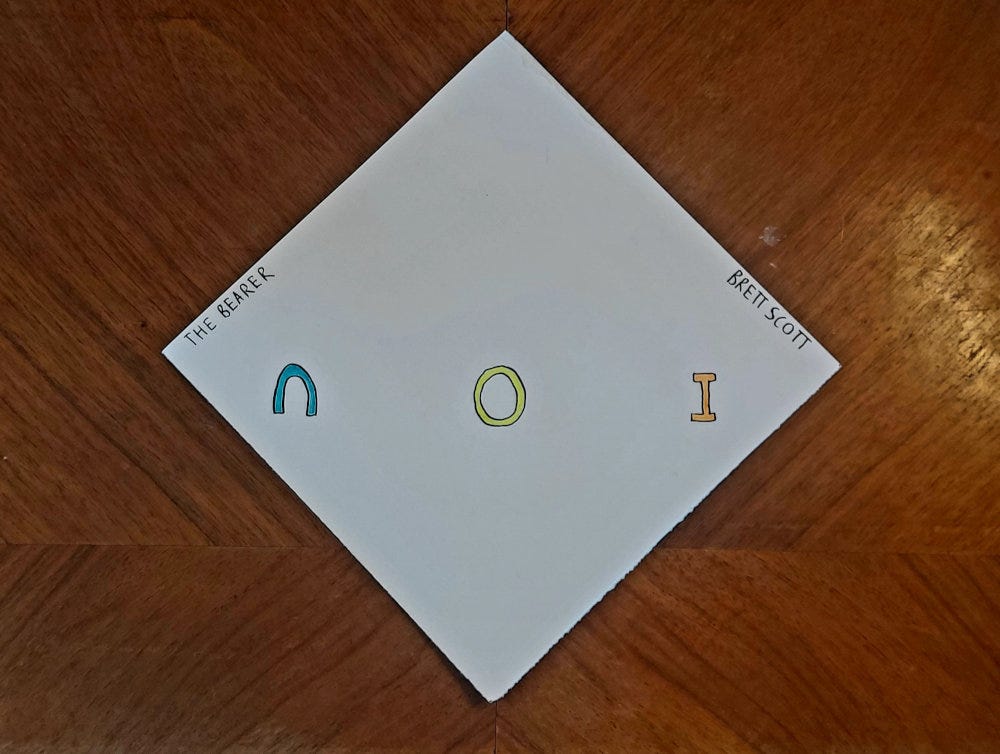

Who is the I though, and who is the U? In my case the I is me, Brett Scott. I’m the one issuing the promise. The U is going to be left open-ended. It will be whoever ends up holding the stablecoin, so let’s just call them ‘the Bearer’. Flip the paper around as shown and write these as follows.

Leaving the bearer unnamed is important, because it makes this a bearer instrument. Whoever holds it is the owner. Some vouchers are bearer instruments (I Owe Whoever Holds This X), and others are not (I Owe Specific Person X).

But what do I owe? The promise inscribed on a voucher could be for specific real goods and services (for example, I owe you three freshly baked muffins), but it could also be a voucher for money (which, in very broad terms, is something that’s come to operate as a claim on good and services in general). The units you see in your bank account are like this: they are Layer 2 vouchers for Layer 1 government money, and a basic stablecoin - similarly - is a Layer 3 voucher for those Layer 2 vouchers.

Let’s ignore the nuances of all that for now, and just write out how much money is being promised. I’m going to promise $100, but with an origami stablecoin it’s a two-part process to write this out. Start with the currency symbol and final zero (see frame 1 below) and then flip it over from right to left and write the rest of the amount backwards, as shown in frame 2.

We now have all the components of the IOU contract laid out, but to bring it all together we need to make the folds displayed below. You start by folding the paper top to bottom in half (1), and then fold it from the top again half way down until you reveal the IOU (2). You then flip it over onto its other side and fold the top half of the triangle upwards to reveal the amount (3). You then fold it in half left to right (4), and make a wing by folding it part of the way back right to left (5). Do the same on the other side to complete a second wing (6).

The final step is to flip it over, make an indentation into the head, and fold the head inwards as follows. Fantastic. This is an origami stablecoin.

Well… not yet actually. Like any promise, it doesn’t really exist until it’s issued.

It’s worth doing a quick aside on this point, because it’s a general feature of all promises, vouchers or IOUs. A promise waiting on the tip of my tongue is just a hypothetical potential promise. It’s only when I speak it out (or write it out and hand it to someone) that it becomes real. Similarly, muffin vouchers waiting behind the counter at a bakery only become real when they are handed out. Before then they are just manufactured pieces of card with a hypothetical promise etched onto them. It’s the social act of handing them out (under a particular legal regime) that activates them. This is also a key feature of the physical cash system: central banks might get third-party manufacturers to produce banknotes, but those only become money once they are issued out by the central bank (for some visualizations of this check out Part 5 of Paymentspotting). Until then, they’re just potential money, waiting to be activated through issuance.

With this in mind, we can see that the origami pigeon constructed in the steps above is just a potential stablecoin, waiting to be activated into a real stablecoin through the act of issuance.

Ok, but in what circumstances am I going to activate it by issuing it out? Bear in mind that if I hand this out I’ll owe whoever bears it $100, so if I hand it out ‘for free’ it means I’m giving without getting anything in return, which is probably unsustainable. So, what should I ask for in return for issuing these out?

It may help to look at some examples of what other money issuers ask for in return. Governments, for example, issue out Layer 1 credits in exchange for stuff like labour for military service, road building, hospitals and so on. Commercial banks, by contrast, issue out Layer 2 units in order to harvest long-term loan contracts from people. The typical ‘Layer 3’ money issuer is a bit more modest in their aims: they only issue out moneyvouchers when someone passes the aforementioned Layer 2 bank-issued money to them (in common language we call this a ‘bank transfer’).

Stablecoins operate in that Layer 3 space, so ask a friend or loved one to take part in your origami craft project by making a bank transfer to your bank account. In my case, I’m going to ask Julio to transfer $100 into my account (for a visual guide of what’s going on in that process, check out my last piece Paymentspotting).

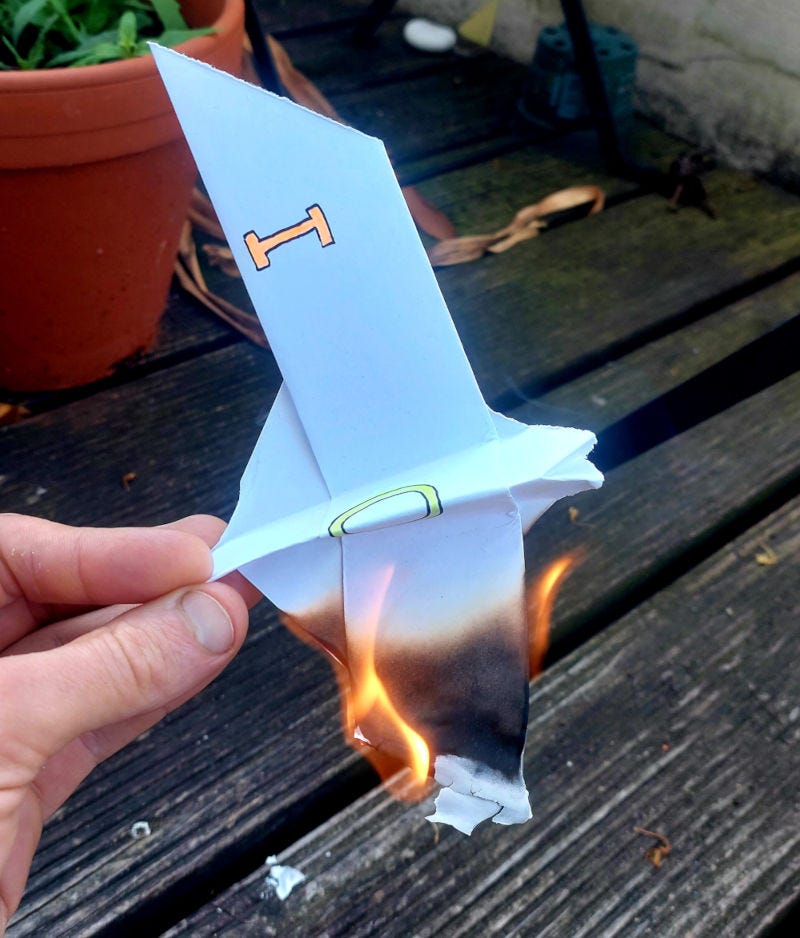

When I see the payment confirmation I will hurl the origami stablecoin at him, thereby issuing my moneyvoucher.

The stablecoin is now in circulation. Because it’s a bearer instrument that only addresses ‘The Bearer’ rather than a particular person, Julio is free to hand it on to others (perhaps in exchange for stuff that he needs), and any of those people can come back to me at any time to demand the redemption of the promise. If they do, I’ll have to reverse the issuance process, transferring bank-money to them and withdrawing my stablecoin from circulation.

I may wish to reissue it at some point, so I could choose to store my origami pigeon somewhere, but if I’m feeling theatrical I could mark its removal from circulation with a ritual burning (alternatively, I could invest in a G+D banknote shredding system, which is what central banks use to upcycle their retired physical credits into colourful briquettes).

Beyond origami

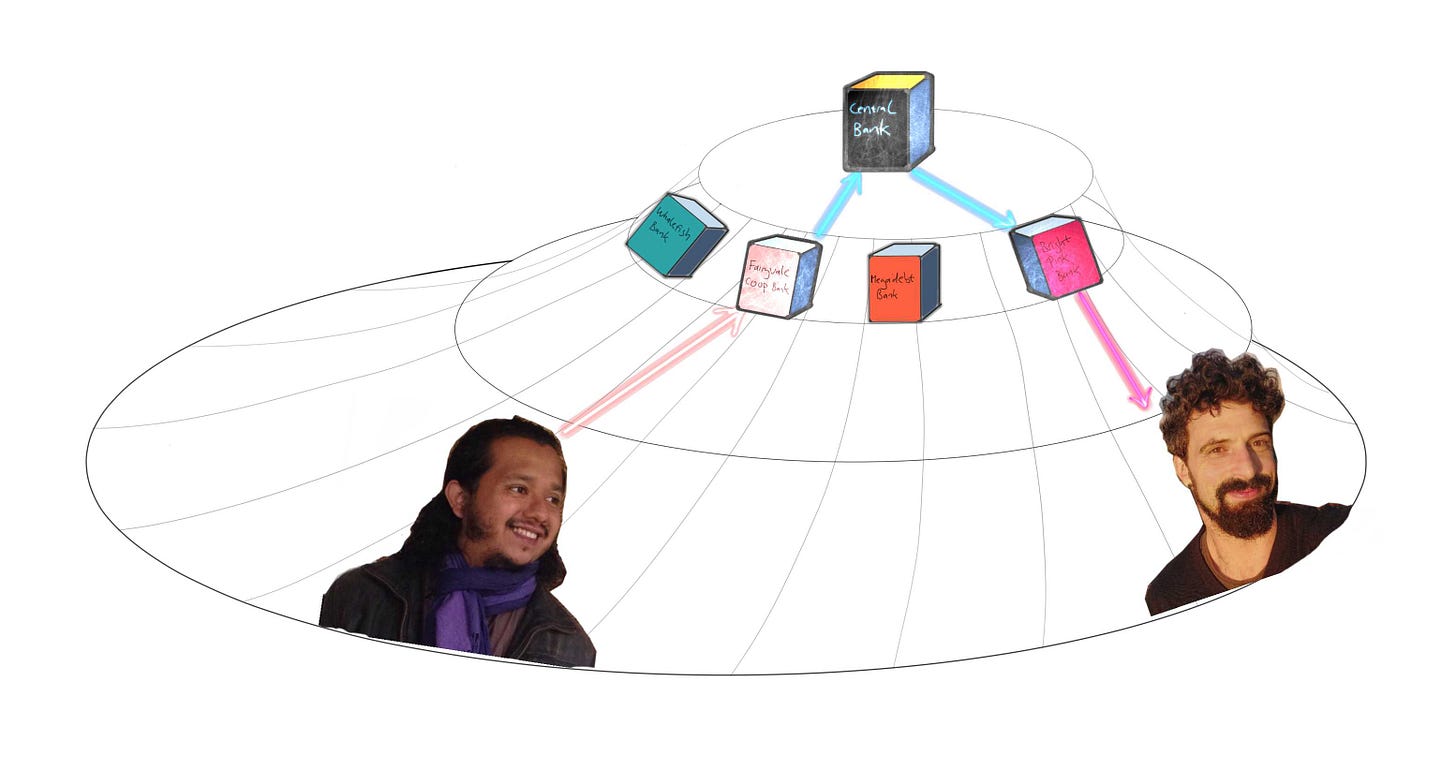

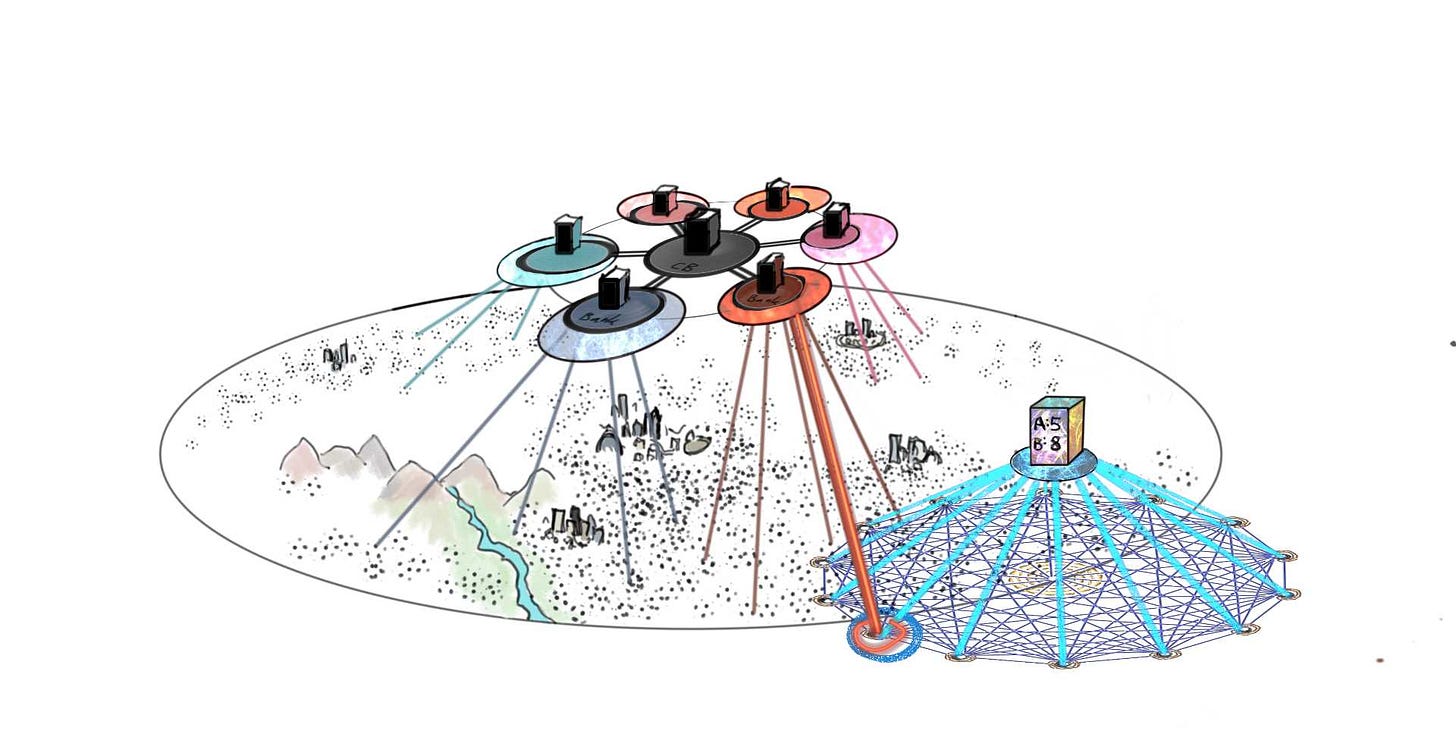

Issuing origami stablecoins is a great craft project for the whole family, but most ‘serious’ stablecoin issuers - like Tether, Paxos and Circle Internet Financial - frown upon this practice as silly. They don’t use origami as the basis for their stablecoin moneyvouchers, and they also have a very different motivation for issuing them. Rather than hurling a paper pigeon at someone who hands them Layer 2 bank-money, they will issue digital moneyvouchers to that person on a decentralised crypto network. The person will see these Layer 3 chips pop up in their crypto wallet, after which they can transfer them to someone else’s crypto wallet. Here’s a (kinda crude) visual representation of that, using some older drawings I did a couple years ago, based on my Hovering Banks series.

The orange circle represents the stablecoin issuer’s bank, and the orange line represents the stablecoin issuer’s connection to that bank via an account. The network on the bottom right is the crypto network that they’re issuing their stablecoins into. The drawing is a bit rough, and probably needs more unpacking to make proper sense to a beginner, but the basic point is to convey the connection between the banking system and the crypto network where the stablecoins will circulate.

Like a lot of Layer 3 money issuers, stablecoin issuers want to harvest your Layer 2 bank-money by issuing you their Layer 3 money instead. Once they’ve harvested it they can claim the interest that you might have otherwise earned on that. This isn’t that far off from the business model of players like PayPal, who also get you to hand over your bank-dollars in exchange for their third-layer chips, after which they can claim the interest, and also scrape fees from you.

The main difference between a PayPal unit and a stablecoin like Tether USDT is the means via which the third-layer voucher is recorded and tracked. The former uses a centralized database controlled by one party, while the latter uses a (theoretically) decentralized database distributed between a number of parties. The former also requires you to have an account with your real name, while the latter allows you to pass around a ‘digital bearer instrument’ simply by having a pseudonymous crypto address.

One of the dubious legacies of crypto-token culture has been to pump out slightly meaningless terms that we’re now stuck with for the rest of time (unless we can convey a global meeting to get everyone to change words). ‘Stablecoin’ was chosen because it was sort of supposed to mean ‘like Bitcoin but stable’, but a better taxonomical strategy would be to say ‘like Paypal but in decentralized digital bearer-instrument form’. A stablecoin is far closer to a PayPal unit than to a bitcoin in nature.

Now onto the most controversial question: should an origami voucher for money truly count as a stablecoin? Well, why not? The whole point of crypto culture is to try create bearer instruments in the digital realm, but a bearer instrument in the physical realm is naturally decentralized in the sense that it passes from hand to hand in a peer-to-peer fashion, and a distant authority cannot send out an order to have it blocked or reversed or whatever. There’s a reason why crypto culture appropriated the word ‘coin’ in the first place, and that’s because the original bearer instrument is cash. My origami voucher is a cash-like instrument (albeit operating in the third layer of the money system rather than the first), so I’m going to appropriate the term stablecoin to refer to it, because language is malleable and I’m allowed to.

Know anyone else who would find this piece useful? Please share it with others!

IOU carrier pigeons vs. algorithmic carrier pigeons

Imagine my physical origami stablecoin as being like a carrier pigeon that transports an IOU to someone. Using this as an analogy, we might think of PayPal as being like a central air traffic control for a flock of digital carrier pigeons. A typical crypto stablecoin system, by contrast, is like a distributed ground network of folks with backyard radio receivers trying to do the same thing. Well, that’s the folk imagination of crypto. In reality the big stablecoin companies are like corporations now, funded by mainstream venture capitalists and cooperating with regulators.

The biggest stablecoin issuers plug into banks, and this puts them in the same league as many fintech platforms, which also plug into the banking sector in the background. That said, the fact that something like Tether USDT or Circle USDC can get passed around on crypto networks like Ethereum means they have a natural synergy with crypto ‘DeFi’ (decentralized finance) platforms. DeFi innovators are attempting to build out the crypto equivalent of mainstream fintech (aka. financial automation), and often use stablecoins as the basis for their automated loans and financial products.

From the perspective of a crypto die-hard, however, the major weakness of any voucher system (regardless of whether it’s implemented on a crypto platform or not) is the I part of the IOU. An IOU only has power insofar as the issuer actually is prepared to uphold their side of the bargain, but that means having to trust them, and that also creates a central point of failure. Stablecoins like Tether USDT were originally like digital black-market promises for US bank-dollars, but they rely on the Tether company to redeem them if you want to cash in the unit for the bank-dollars it promises. That means if the authorities seize the assets of the Tether company or freeze its bank accounts (which hold the bank-dollars that back the units), the entire ecosystem is at risk. For crypto hardliners, who yearn for an algorithmic world controlled by unbreakable protocols running on distributed hardware (rather than their human brethren), this is unsatisfactory.

This is why the holy grail among purists is to create a unit that looks like a digital IOU carrier pigeon, but which actually isn’t. They want to create a DeFi ecosystem that behaves as if it were backed by the power of the US state and its financial giants, but without actually being backed by them. This is why there’s been many attempts over the last few years to build so-called ‘algorithmic stablecoins’. I used to work in financial derivatives, and one of the standard ambitions of derivatives structuring is to artificially synthesise the effect of holding a particular financial instrument, or of being in a particular situation, without actually holding that instrument or being in that situation. Algorithmic stablecoins, similarly, want to synthesise the effect of holding a digital US dollar without you ever having to hold it. In practice this normally means holding some Frankenstein-like unit constructed from a bunch of digital parts, which has its price regulated via a very-hard-to-understand automated trading mechanism that very well might fail.

The politics of Layer 3 money

I can carry my origami moneyvoucher in my hand luggage when I go visit my South African family, and hand it to my brother, allowing him to hold a US dollar voucher without having a US dollar bank account. My brother might even be able to pay one of his employees with my stablecoin, allowing him to bypass a typical cash or bank transfer.

You might think that’s useful, but one reason why stablecoins are politically controversial is that they allow powerful - and, one might say, imperialistic - currencies like the US dollar to make incursions into the lives of people far away. In doing so, they can increase dependence on foreign currency, and that’s political because the people of South Africa have exactly zero political say in the management of the US dollar system. From a superficial perspective, the fact that US dollar stablecoins are issued on decentralized crypto systems might make them look subversive and challenging to the US state and its banking sector. In reality, however, they can operate to extend US hegemony. The same goes for stablecoins issued for any other powerful currency.

It’s also worth noting that a standard stablecoin is a voucher for a voucher for money (which in turn can operate as money), but there are many other things that are like this too. In fact, there’s a giant universe of ‘Layer 3’ units that go under all sorts of names. For example, if you ever hear the term ‘electronic money institution’, it’s often referring to a Layer 3 player. Similarly, the somewhat arbitary term ‘virtual currencies’ is often used to speak about Layer 3 units: my origami stablecoin is a virtual currency, but so is stuff like company-issued coupons, in-game currencies, Amazon Coins, Facebook credits, and even air miles (given that they’re really a kind of voucher for monetary discounts off future flights and services from the airline). The digital money units you might see in your account on a share-trading platform are third-layer moneyvouchers, and so are those on an online poker site.

There might be a difference between physical and digital implementations of these different units, but at a structural level they all circulate in third layer orbit around the centre of the monetary system. One of the key skills to learn is to be able to separate out the body of these tokens from the promises they may carry. I could etch a voucher for $100 on a piece of metal, or I could write it down on an Excel spreadsheet, or I could record it on a vast distributed database that’s held in play by 10,000 strangers across the world and rename it as Brettcoin. In the end, on one dimension at least, it’s the same thing: a voucher for $100. The form of the body, and the affordances it offers, can certainly make a difference to how the voucher might be used or abused. That said, being able to see through the body, and into the social and political web within which the promises it conveys get activated, is a sure-fire way to level-up your monetary understanding.

If you’ve got this far and have found this piece useful, please give it a like, share it and leave a comment!

Dear Brett,

This "origami stablecoin" article gives me strength to write a similar article about the Turkish IOU system (called the Vadeli Çek), which works with blank A4 papers (like your origami IOU) or with bank issued paper cheques. In either case, an issuer with her signature "issues" Layer 3 credit based on her Layer 2 bank account, using Layer 1 Turkish central bank lira as denomination. This mechanism is used (to create personal credit) in Turkey by over 500,000 people and transact more than 1 Triilion TL every year. The mechanism works exactly like what you described in your origami IOU exercise, except for a time value added on the IOU. Hence, there is an expiration date on the Turkish IOUs and the issuer is not liable to put money in her account until that date. This mechanism is protected with a special "Vadeli Çek" law.

Glad you’re creating articles again. This was a good one! (Saying as someone who stays far away from getting involved in crypto)