Paying subscribers can access the audio version here (21 minutes)

When we see money as a thing with value, we often mistakenly imagine it in absolute terms, as if value resided within it like a substance. In this view, a person with a billion dollars is like Pooh Bear with a giant pot of honey.

It would follow that if everyone was a billionaire, we’d all be like Pooh Bears with giant pots of honey.

Thinking of money like this is a mistake. In fact, if everyone in the world was a billionaire we’d all have nothing. In this piece I’ll explain why.

The foundations of value

Our ancient hunter-gatherer ancestors understood one thing very well. While the most basic foundations for our survival - such as sunlight, air and rainfall - come to us for free and without effort, pretty much everything else we value comes from us applying our energy to the earth.

What we call ‘the economy’ is a network of human beings who use bodily energy, and other forms of energy, to collaborate in bringing things to life. We often imagine that value resides in these products themselves, but goods and services don’t drop out of the sky: they emanate from people who transform natural resources, so in a sense all future objects, and future economic value always resides in those people and in the environment.

This formula applies regardless of the style of economy. An ancient hunter-gatherer band brings value to life at a very small scale with a small network of people who explicitly perceive themselves as collaborating. A modern market economy happens to do this at a much larger scale, with a globe-spanning network of people who are held together by monetary systems rather than by direct relationships, and who often don’t perceive themselves a collaborating. Still, if you rely on people on the other side of the world to make your breakfast cereal appear, you’re collaborating with them. It’s just that the collaboration is secured via the transfer of monetary credits.

Value never resides ‘in’ that money. It resides in the network of people, plants and sunlight that’s making the cereal you rely on. Monetary credits, though, will open access to those people. This means, when you’re accumulating money, you’re not accumulating stuff. You’re accumulating power over others who can bring stuff to life.

Being ‘rich’ or ‘poor’ refers to how much power you have to mobilise others in an interdependent economy, relative to the amount of stuff or labour you need on average. A poor person needs a certain amount, but has very little power to command other people. A rich person has large power, being able to mobilise many others through their accumulation of monetary credits, but they can also start to artificially need more stuff. There are many examples of aristocrats bankrupting themselves because their giant mansions cost an enormous amount to maintain.

Money itself doesn’t do that maintenance. People do. But if an aristocrat loses all their money, they lose their ability to make those people turn up to do that repair, and that’s how the value starts disintegrating. It superficially looks like it’s the absence of money that causes that erosion, but it’s the absence of people.

Starting on zero

An interdependent economy has to be seen, on the one hand, as a collective whole with a certain capacity for action. Let’s imagine a classic ‘desert island’ situation in which an 18th century crew gets shipwrecked on a Pacific reef. Let’s say eight survivors manage to get to an island where they must collaborate to survive. There’s a certain potential in that group, but it’s limited by how many of them there are, and how much stuff there is to extract on the island.

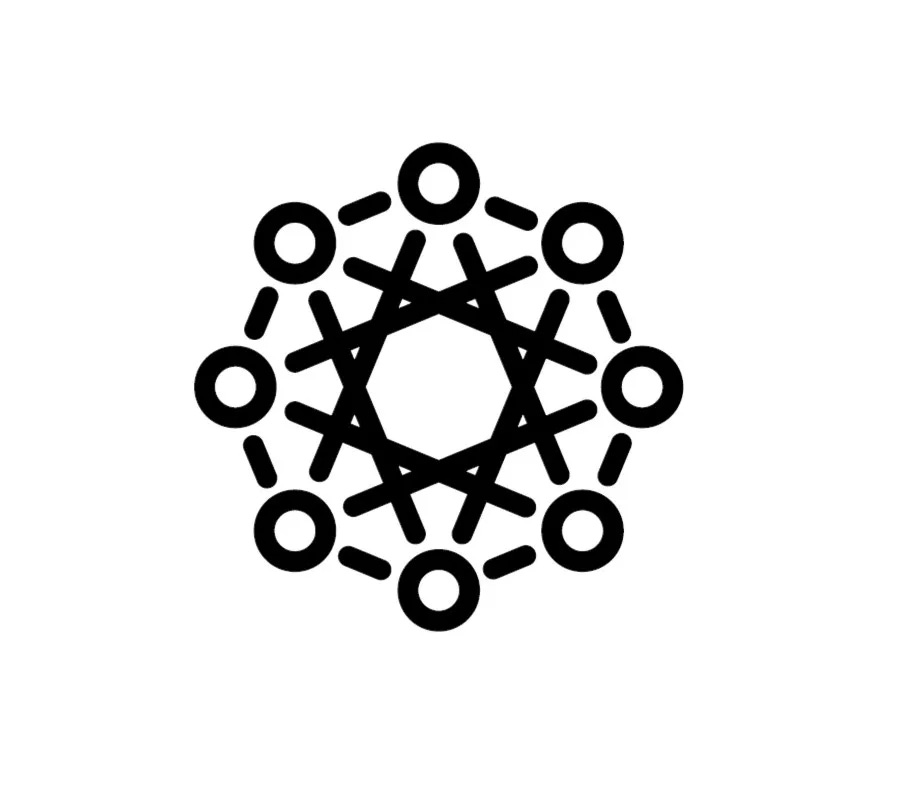

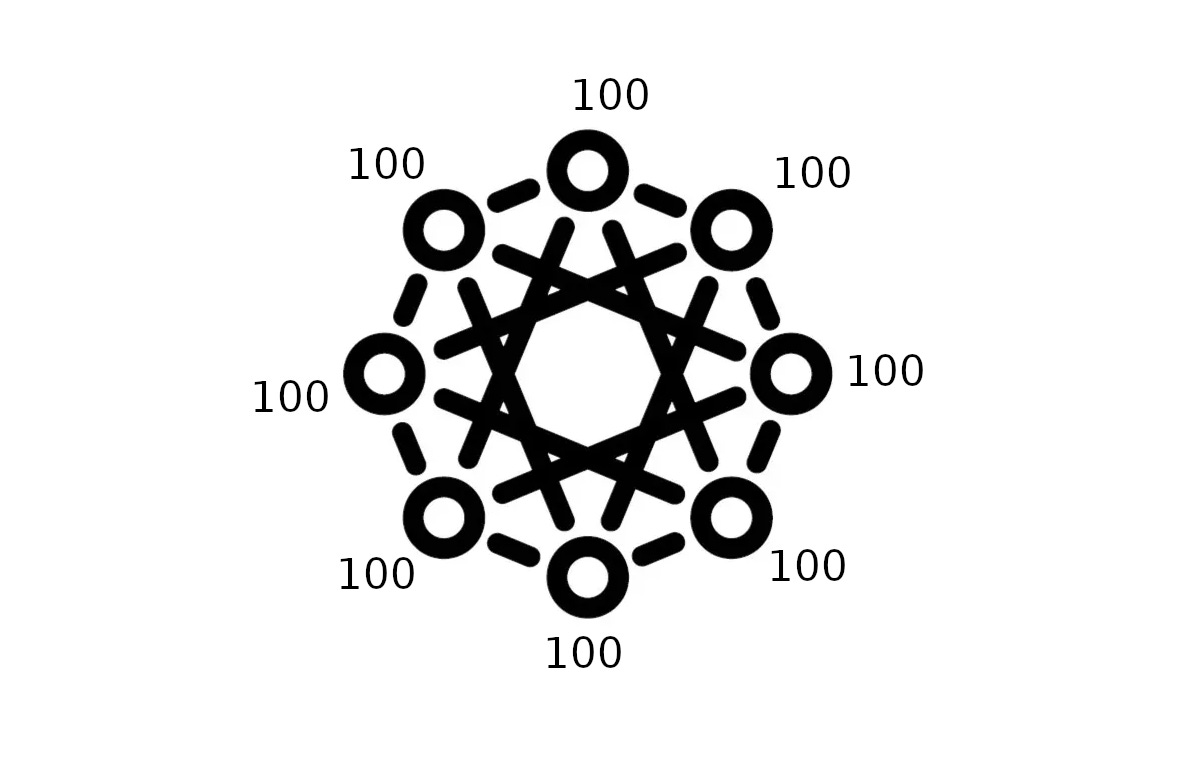

The eight survivors and the island will form an economy, but while they are a collective network, each crew member will still have an individual identity, and a sense of how they relate to the others. For simplicity’s sake, let’s imagine that everyone arrives in a situation of equality, with equal capacity for action, and equal status. Imagine the image below as them huddling in a circle on the beach, saying ‘we’re all in this together’.

In the diagram above there are a network of interpersonal relationships, but we’re going to assume that in this scenario everyone has a clean slate, starting from scratch. If we isolated one bilateral pair it might look like this.

Zero is a point of balance between positive and negative, like the centre of a see-saw. At the very start, everyone is balanced in this state of equality with everyone else, but they must proceed to survive on the island, individually contributing skills and energy to different tasks that the collective requires.

Insofar as everyone simultaneously contributes exactly equally all the time, they’ll remain in this state of balance, but human society doesn’t really work like this. What actually occurs between people and groups - whether those be housemates, work colleagues, band members, or shipwrecked crews - is that subtle gradations and fluctuations away from the zero line occur, as some people extract more than they’re contributing, and vice versa. As a person draws on another, they’re moving into a sense of debt to that person - going negative - while the other moves into a sense of credit - going positive.

Like a see-saw, there’s a limit to how far someone can go into the negative before the other stops them, but this will also be but one strand in that group setting.

The negative number here doesn’t represent a moral failing. ‘Going negative’ relative to others is a core element of community life. In fact, before you can engage in action for others you often need others to first support you, and communities are woven together through these shifting webs of informal reciprocity in which you move from ‘debit’ to ‘credit’ and back again. In the image above I’m representing this numerically, but these ‘balances’ are seldom explicitly measured or formally recorded. We just have an intuitive sense for them.

In a interdependent group those bilateral pairings will start to criss-cross and overlap into meshes that move beyond single pairs of people. For example, you might find two people going negative as they draw on one person, who goes positive relative to both.

The twists and turns of life on the island experienced by our crew will create a fluctuating mesh of ever-shifting balances between single people, single people and sub-groups, and sub-groups with other other sub-groups.

If you add all the network balances up they come to zero. This zero is always implied in the webs of interdependence, and represents - at some level - everything that’s produced and used by the overall network, or the baseline living standard.

Ok, I say ‘everything’, but that’s not entirely true. The anthropologist in me is obliged to note that there’s a world of activities beyond tit-for-tat reciprocity that will play out in economies, and which do not accrue these ‘balances’. We don’t have time to go into those right now, but turn to the the late David Graeber or check out my Econ Life 101 course if you want to delve deeper.

Power differentials, and market economies

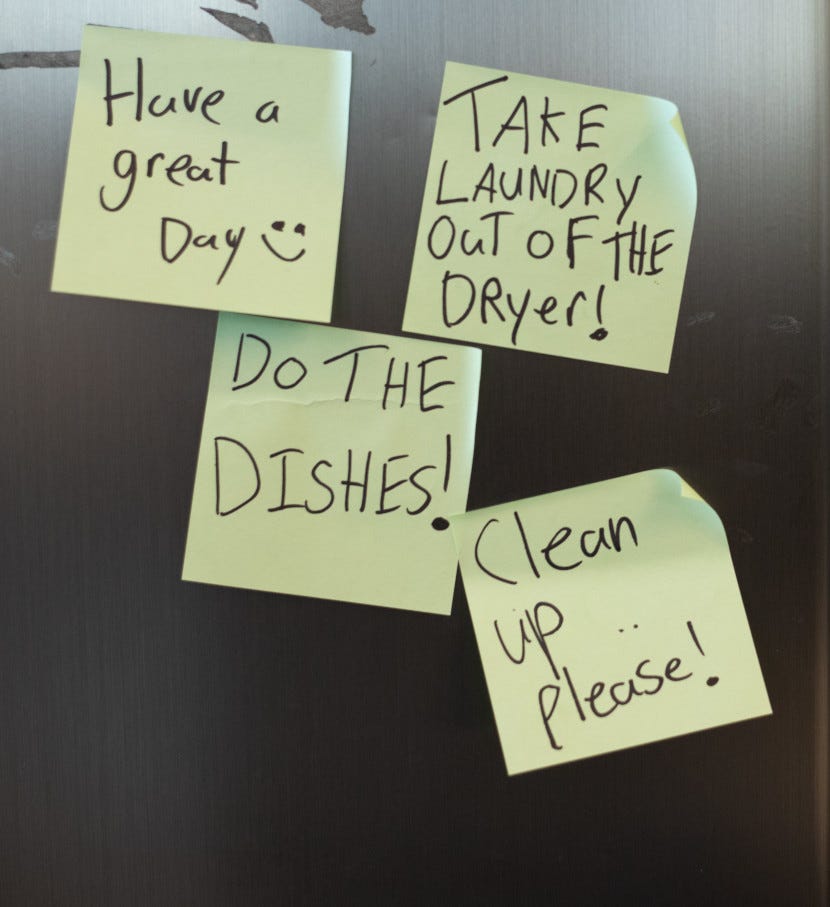

With this basic picture in place, we can play with it. For example, we might ask ourselves whether it’s technically possible for everyone to collectively dip below zero as a group. Well, insofar as the zero line represents the baseline living standard, we might find situations where a group drops below their own expected standard. Picture stoner students living together in squalor, on the couch letting plates pile up, before someone says ‘hey guys, we haven’t done the washing for a week. Maybe we should’.

For now though, let’s assume that a single standard holds. In most informal situations, the sense of who is in debit and credit relative to that happens intuitively, but if you wanted to formalise this, you could imagine that those who are below the zero line have formally issued credits to those who are above it, giving those above it the right to call those in and demand stuff back. When a person says something like ‘I’ve been doing the washing for the last week while you’ve been watching TV, so now it’s your turn’, what they’re saying in formal terms is: I’ve done services for you, so I’ve accumulated positive credits from you, and now I’m cashing those in to make you do services for me.

Notice that when there’s a network imbalance, it can create a power differential. Much like air moves from a high pressure zone to a low pressure one - creating winds - goods and services can move from high debt zones to those with positive credits. Put differently, people in credit have the power to command others, especially those who might be reaching the limit of what others are prepared to give them.

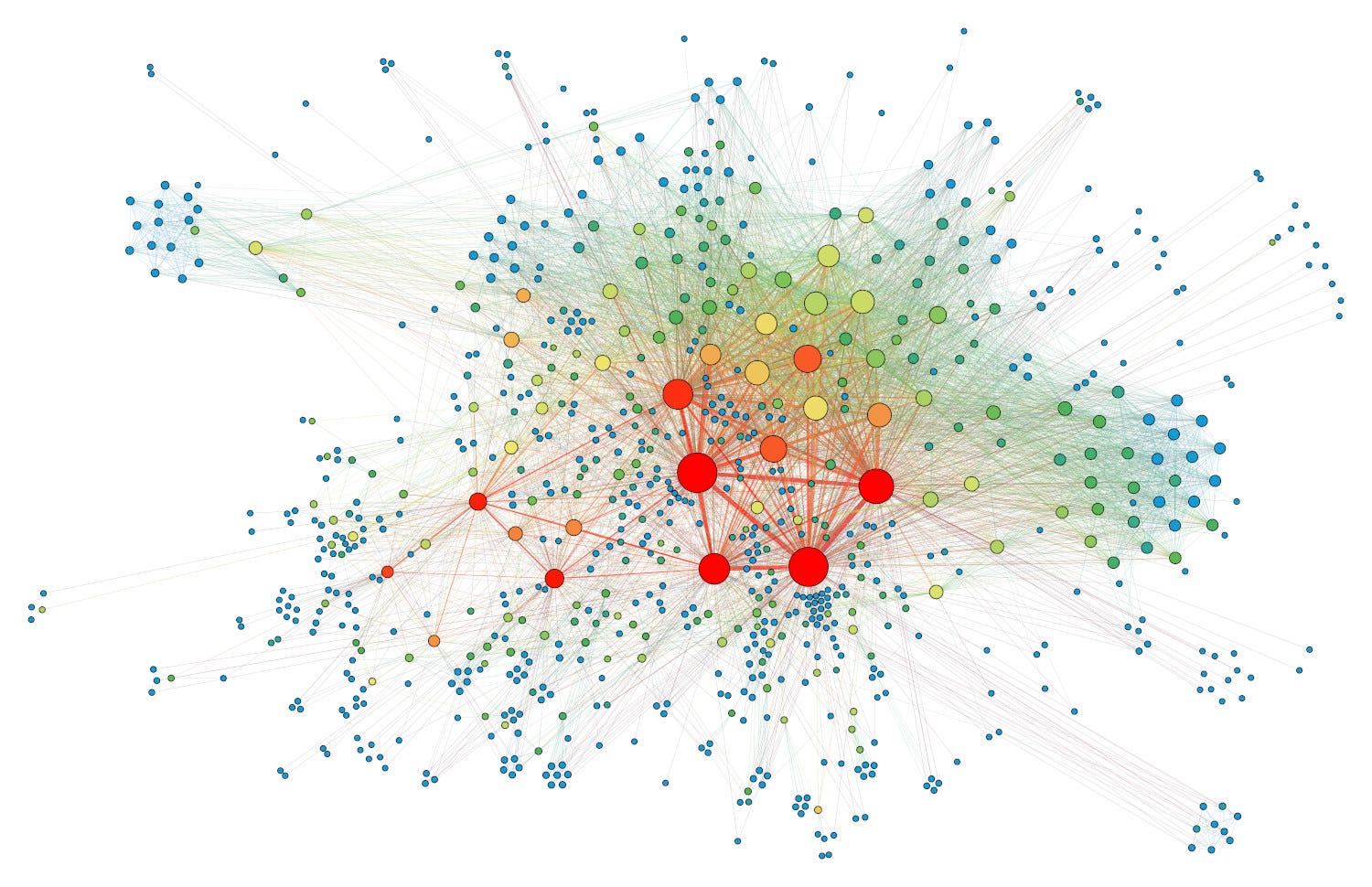

I’m going to skip a few degrees of complexity here, but our modern market economies are a vastly more convoluted version of this situation. Rather than eight people on an island keeping intuitive track of informal balances between themselves, there’s eight billion people on a planet, locked together within a system of formal monetary balances. The complexity of this system is massively greater, but shares a common feature: we have interdependent people with different states of network power.

At this point I must make one thing very clear. You’ll note that in our earlier examples we assumed that those in credit have been working hard, and are thereby deserving of stuff, but there are many ways to accumulate positive credits without working, and many situations in which people go negative while trying their hardest to work.

I can’t cover all of those right now, but let’s focus on a classic one: if you own something that everyone else always needs to reach a particular living standard - such as a type of infrastructure - you can sit back and extract what’s called rent.

Let’s go back to our shipwreck example. Let’s imagine that one out of our eight survivors actually happens to be a violent and intimidating captain who holds a key to a storeroom that remains intact on the wrecked ship that’s now washed up on shore. There’s food and ale in that storeroom, and everyone is hungry and desperate, so he can use that to become a gatekeeper of sorts, extracting positive credits in exchange for allowing access to this resource he controls.

The first thing that happens here is a network inequality. He begins to accumulate credits relative to everyone else. Secondly, given that the power swings to him, he can secure favourable terms for the amount of credits he extracts. Economists might try to analyse this through the lens of ‘market forces’: given that nobody else has a key to a different ship to provide an alternative, they cannot dilute the captain’s network power. In fact, he might entrench that power by granting unequal access to allies in exchange for protection from the rest of the mob. With his bodyguards in place, a hierarchy builds.

This is actually quite similar to the situation of most billionaires in a market system. Jeff Bezos gets rewarded with positive credits every single day, regardless of whether he turns up to work or not, because he owns an infrastructure that others actually operate. Ownership is a legal concept underpinned through force, and Bezos himself doesn’t do that enforcement. That’s done by military and police.

If Amazon.com consisted solely of Bezos, it would be a tiny company with one guy trying to deliver single packages. But it’s not. Amazon.com is 1.6 million people that activate the assets that one guy happens to have a controlling ownership stake in. At a global scale, the actions of countless Amazon drivers making early morning deliveries leads to a huge influx of positive credits rolling in to Bezos as he walks around in his pyjamas drinking a smoothie. Those positive credits will enable him to call in collossal amounts of labour from billions of human beings across the world.

So, one of the main ways to get wealthy is through controlling the infrastructure and capital goods that everyone else requires. This tends to be positively reinforcing, because if you end up in a position of unequal power you can direct the productive forces of others, making them build new assets for you (alternatively, you can retroactively buy up assets that previous workers made). Over time, this leads to concentration in who owns the ‘means of production’ that are required by everyone else to access or compete on markets.

When viewed as a class of people, those like Bezos become gatekeepers to survival, positioning themselves as an oligopoly of power players at the centre of a market network.

It’s a position that allows them - or corporations run by them - to extract even more wealth, which they can then use to further solidify their political power through lobbying, marketing, or buying favour through philanthropy.

At this point I must highlight one massive elephant in the room. In our system we also have the financial sector. This is a web of institutions that weave a transnational mesh of contracts that extend positive credits in exchange for extracting a shadow future liability over and above the current capacity of the economic system. The monetary profits that will stem from decades worth of future production are already claimed within this web of financial instruments. I know that sounds complex, and we won’t delve into it in this piece, but the ability to harness this system favourably is one major way mega-capitalists secure further power.

But while it’s true that many forms of exploitative inequality can emerge in a large scale market network, the network remains subject to two principles that apply to all economies throughout history: firstly, a positive balance only has power insofar as there’s a negative counterbalance - aka. other people who can be mobilised by that balance. Secondly, there are limits to how much capacity that counterbalance carries.

Let’s return to our domineering captain who has extracted a highly unequal amount of credits. His ability to turn those into stuff is limited by the number of people he has power over. If he only has seven people to command, there’s only so much they can do in a day, and only so many resources they can do that to. Maybe the captain can make them construct a small beach shack out of driftwood for him, but if he desires a huge mansion of marble there’s no way he can convert his power into that desire. He’ll hit a network limit very quickly, exhaust his credit, and might also inspire a revolution against him.

In the case of Bezos, the network of people is much much bigger, so his ability to convert his power into goods and services is much greater, but there’s still a limit. Furthermore, the more credits he uses mobilising people towards that limit, the more his power to command runs down. He might end up with a huge mountain of goods, but as the network reaches equality of credits, he’ll find himself with very little power at all. Put differently, his power depends on a big differential in credits.

Resetting the zero line

Once you recognise this dynamic, you can start to see money as a system of credit balances that only make sense in relative terms. To illustrate the quirks of this, let’s rewrite our original shipwreck example. Picture the crew washing up on the stormy shore. They huddle together saying ‘we’re all in this together’, but then, in a strange twist, decide that everyone starts on 100, rather than zero.

Is this scenario any different to the one we began with? Well, no. We have the same eight people, with the same capacity, in the same situation. The only difference is that they chose to name their starting position 100 rather than 0, but there’s perfect equality and no power differential, which means - in reality - nobody has a positive balance that can command others. In fact, they all have nothing. They might as well just call it zero.

In reality, what’s happened is that 100 has become the new zero line, and this is where things get really trippy. It superficially looks like there are positive balances here, but there’s no money in this situation. Money is a system of unequal credit balances that generate the ability to command others, and that only exists when balances move out of alignment.

So, let’s observe the same behaviour as before. The crew start life on the island, and begin having those fluctuations away from the starting position, but if your zero line has been renamed as 100, the act of someone going to 90 is the same as them going -10. The person who has gone to 110, by contrast, actually only has 10 units of money. The rest is illusion. What we’re looking at is the same differential expressed from a different baseline.

Incidentally, the failure to understand this plagues many people in the crypto-currency community, which has a very strong tendency to view money as if it were solely a system of positive balances, like an absolute pot of honey. For example, crypto projects sometimes do ‘airdrops’ in which the same number of tokens are dropped from above onto people, which is then imagined to grant those people ‘stuff’. If we leave aside the question about what exactly those tokens are, and just assume they actually carry some kind of power (which, in the case of crypto, is a dubious assumption), we can see that dropping the same power onto people just cancels itself out. If everyone is a lion, then you’re actually all gazelle.

The only reason that Jeff Bezos can command huge amounts of stuff is that there are billions of people in his network with low or negative balances that need to grope towards the systemic zero line, and his enormous collection of positive credits will suck that labour towards himself, which can manifest as a huge yacht or mansion or whatever. The labour and resources do not emanate from his monetary tokens. They emanate from that pressure differential between him and others that emerges through unequal credit. ‘Billionaire’ then, doesn’t refer to a property residing in a single person in a vacuum. It refers to a property residing in the relations between that person and everyone else. It’s this differential that creates that ‘suction’.

If ‘billionaire’ actually means ‘person with enormous amount of credit to hoover stuff up from others’, what would the statement ‘everyone a billionaire’ mean? Well, it would mean ‘everyone with enormous amount of credit to hoover stuff from everyone’, but what does this mean? Well it could mean everyone slaving away for everyone, but that’s likely to cancel itself out, like a giant army of Bezos’ trying to make each other build skyscrapers, screaming ‘you do it!’, ‘no, you do it!’

Markets are not systems of numerical quantities of stuff. They’re systems of power. That said, power is a relationship between people, and as such has more than one face. While it’s true that the captain has the power to make the other seven rush to do stuff for him, it’s those seven who hold the labour power that he seeks. If they withhold that, the captain soon grows hungry, lonely, cold, and weak.

Seems like a good opportunity to talk about UBI. I’ve always wondered how it would work at a national scale. You’re changing everyone’s current position by the same amount. But of course that increase has different implications for your life depending on how close to zero you are.

On the other hand. UBI doesn’t change the hoover that’s vacuuming value upwards. So does UBI simply result in greater value moving from the gov’s budget to corporations?

Hi Brett,

I'm a real novice mind when it comes to economics and am trying to wrap my head around much of what you've written here. Have you ever, or would you ever, do a piece on a specific type of so-called "green" or "renewable" energy development and the economics of this. I'm doing some grassroots activism to protect my west coast from Offshore Wind development, and although I have the environmental aspect of it covered, I'm interested in learning more deeply about the loads of subsidies required for these massive industrial projects. Of course, the rate payers pay for this, and the loans are taken from our taxes. I would love to hear some of your thoughts on this stuff. As an anthropologist, I'm sure you can appreciate the level of cultural disconnect when we talk about the Earth as a "resource" to be extracted from. Obviously, we've gotten ourselves in a conundrum when we extract faster than Earth can replenish and waste faster than Earth can absorb. It seems so obvious, yet almost impossible to clarify to someone who believes that we've done a great job as a civilization. As someone working with my local tribes, it's clear how so much of economics is how we've been groomed to think about Earth and our relationship to Earth.