Intro to Economic Life 10: The Re-Growths

Five paradigms of change

It’s very easy to spend years fighting people you disagree with, but how do we start to think more strategically and empathetically about our troubled economic system?

The first step may be to realise that our diverse and conflicting perspectives on economies often stem from a common source: the need for survival, inclusion, identity and meaning. It’s important to remember that our global system of large-scale fluid interdependence (see Part 6) is very hard to see, which means people can project all sorts of visions onto it from their particular vantage point. That vantage point shifts by geography, economic strata, culture and sub-culture.

We’re group animals, and if you’re hanging around others in a particular social group who’ve come to believe that our system is one particular thing, you could very well start to see it as one thing too.

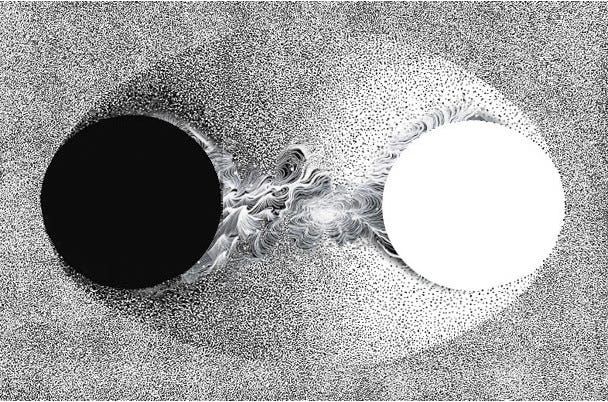

There’s a long tradition in Western philosophy of ‘one-thingness’, the attempt to describe reality through discrete objects that supposedly have independent existences. Here is Capitalism. It is one thing. Here is Communism. It is a different thing. They are separate objects that fight each other.

From the very beginning of this course, however, I’ve suggested that these imagined pure forms are abstractions. From the earliest human economies, we’ve always lived with simultaneous conflicting moral logics that can be neither reconciled nor separated from each other (see Part 3). Even in the most capitalist society, everyday communism abounds, despite the constant attempts of the system to commodify everything. Similarly, in the heyday of state-sponsored Communism, all sorts of trading was at play.

I have often used that term ‘capitalism’ in this course, but I’m not referring to a set structure that remains constant. Rather, I’m referring to a strong tendency within our economic web, which coexists alongside other tendencies. These tendencies cannot really be placed on a battlefield against each other, with some eventual winner, because all of us have all the tendencies within us (see Part 2).

One way to grasp this is through a sensory metaphor. Most of us simultaneously have five senses - hearing, sight, smell, touch, and taste - but it might be the case that you’re particularly sensitive to one or another. Perhaps you’re a visual person, or a tactile person, but you still have four other senses.

Similarly, in our search for identity, inclusion and meaning we often end up sensitized to one or other moral logic in an economy. We might latch onto it, but it doesn’t mean we don’t carry the others with us. A person who calls themselves a ‘libertarian’ will behave socialistically every day, and yet form their identity by railing against Socialism, spotlighting one part of themselves by contrasting it with another. Similarly, ‘socialists’ have capitalistic traits, but push that to the margins of their identity.

We all have multiple forces co-existing within us, and are constantly exposed to multiple forces co-existing within our economic system. This becomes important in thinking about how you build ‘alternative’ systems.