Intro to Economic Life 101

Why I'm building an 10-part course to life under corporate capitalism

Paid Subscribers can access the audio version here

As a kid I was perpetually confused as to what ‘the economy’ was. On the one hand, my environment seemed saturated by its markers: I could touch products in shops, watch money passing from one person to another, see people doing jobs in companies that had logos, and hear adults asking me ‘what do you want to be when you grow up?’ On the other hand, my environment seemed devoid of any instruction manual to help me navigate this assemblage of people, products and firms. There were news reports about economic conditions, but I could never detect the overall point, structure or logic of it all. It had a mystifying quality, but not the good kind.

The economy was utterly confusing to me, but everyone around me seemed to share some common understanding about what you were supposed to do in ‘it’. Teachers would tell me that I needed to study to get a job, so that I could get money to buy things. This unquestioned common sense was supposedly all I needed to know, and my peers saw it as ‘obvious’. That’s what made me anxious. To me it wasn’t obvious. How were you supposed to know what job to do? Why did certain things have certain prices, and what did the numbers refer to? Why did I have to buy these things? Where did they come from?

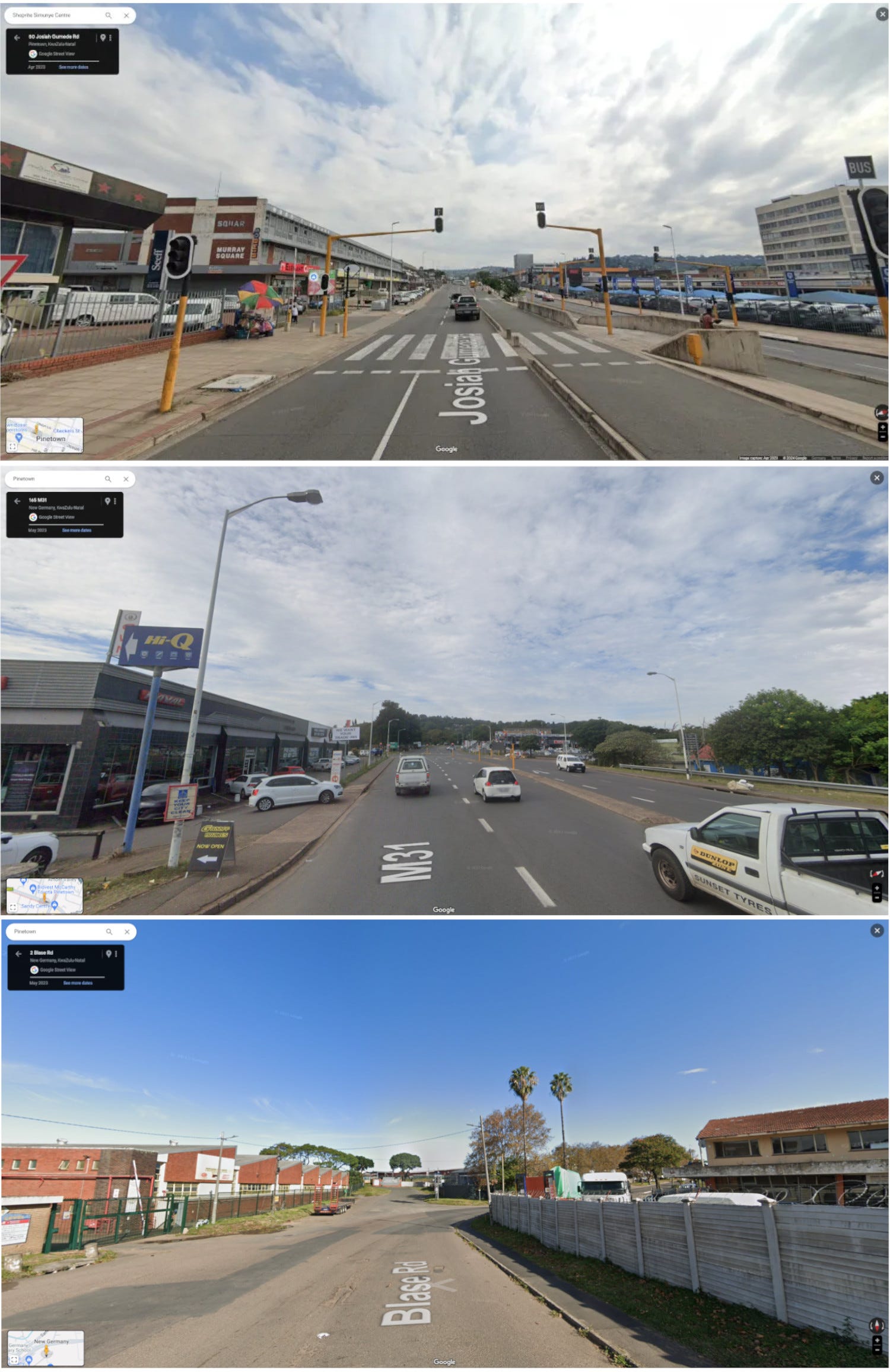

I grew up in Pinetown, South Africa. Pinetown is technically a ‘city’, but feels more like a backwater extension of the much larger metropolis of Durban, which lies 20 minutes by car from it. When I’m back there, I drive through its streets and see the world briefly through the eyes of my old teenage self.

Pinetown’s peripheral status, and lack of economic centre, is perhaps one reason why I was so confused about economic life. Kids can only really experience what’s directly in front of them, but Pinetown never showed me any complete picture of an ‘economy’. It seemed a non-place, full of light industrial warehousing, tile manufacturers, and parking lots with delivery vans next to bland office buildings for SME businesses. I used to stare out the car window at these entities and feel that sense of confusion as to why these things were here in particular. Even if I tried to zoom out to a birds-eye view I could make no sense of it.

I suspect many people have a similar confusion growing up, but perhaps are forced to shut out that part of themselves that asks questions. We perceive local instances of economic life - stuff in a supermarket, a desk in an office - but don’t perceive, or even necessarily believe in, an overall structure. Being in an economy is like being in a weather system. The idea that you would try understand it before slotting yourself in is like a person trying to understand a storm system before deciding what coat to wear. Most people see no point in that. You’re supposed to just accept the hand you’re dealt, and then simply adapt by copying others, or taking the designated path that your background, family wealth or training makes available to you. In the midst of adapting, you’ll also adopt certain basic mythologies as to what you’re doing, and the morality of it.

My social strata in Pinetown was characterised by a ‘petite bourgeois’ mindset. South Africa is deeply racially segregated, especially at that time. The parents of people I was at school with were often owners or managers of small-scale businesses that did stuff like signpost printing, pool installation, or tire realignment. Their badly-paid workers would often be black people who lived in cramped townships outside the white residential areas. The classic image of this in South Africa was (and still is) the white owner-manager driving a ‘bakkie’ (an open-backed pickup truck) with his logo emblazoned on the side, and three of four black workers sitting in the back.

This was a pervasive image for me as a kid. Every road in Pinetown had these bakkies driving to and from different appointments. When my dad needed something done - like a new fence put up at our home - one of these boss-driver-managers would turn up at our house for a chummy chat while the workers waited in the background, talking among themselves in Zulu.

The economy seen through the eyes of a black South African worker in 1989 is very different to that seen by a small white child watching them, as the manager barks orders to offload the fencing wire from the bakkie. My dad standing there made this kind of thing feel normal, but what would feel normal to a Zulu kid as their dad came back home from his fence installation job? What would they imagine their future role in ‘the economy’ to be, and how would that differ from me? I guess they were imagining a future in which they had to work in manual labour, whereas in my world the basic message was: get a mid-level management job or start a small company, form connections with others like you, pay your debts, save money, get a house, buy a microwave, go to church on Sunday, watch the rugby.

The problem for me was that this set of expectations made no sense, and - for some reason - I assumed things were supposed to make sense. My stubborn confusion is one reason why I became ‘intellectual’, trying to question and decode the strange environment around me. This path eventually led to me being drawn into anthropology at university, and - eventually - throwing myself into a wild anthropological adventure in the global financial sector in 2008. I ended up as a financial derivatives broker in London, in a world of hedge funds, investment banks and corporations. I’d do weird stuff like turn up at the offices of corporate giants to pitch dubious ‘property derivatives’, but driving all of this was a yearning to get a high-level view of ‘the economy’. I believed that if only I could get inside the titans of global capitalism, I would gain some insight into what my earlier self was so confused by.

In the process I discovered (at least) two major things. Firstly, most people in the financial and corporate sector were also confused. London’s financial sector is a huge magnet for people from across the world who’ve detached from their respective ‘Pinetowns’. It turns them into high-flying jet-setter types who can structure a complex derivative, but deep down they can’t explain the most basic elements of economic life, like their emotions about money, or why their mother worked long hours, or why they now wear a suit like a protective uniform.

Secondly, I discovered that while confusion is common across different parts of our economic system, the parts interlock at different scales, and the implications of being confused at those different scales differ. Some of those property derivatives I worked with were bets on the prices of large collections of retail warehousing properties. They would, in essence, take all those drab buildings that sit on the edge of cities in all those non-places, and abstract them into a numerical ‘index’ that could become an object of speculation. They were part of a broader class of financial instruments that specialise in squashing thousands of separate smaller things into single huge things, so that huge financial investors can just deal with one generic thing - like ‘UK retail warehousing’ - rather than dealing with a thousand investments in specific things in specific places, like a garden centre on the outskirts of Slough.

In the grand scheme of things, South Africa is a small player in the global financial markets. This means that there are not enough specialist investors there to support a property derivatives market, but if there were, a single grubby mall in Pinetown might hypothetically form one tiny part of an index for them to bet on. Its price might be dragged down by the encroachment of informal slums across the hill, but that might be offset within the index by the inclusion of a fancier shopping centre in the suburbs of Durban, and an even fancier one a thousand kilometres away in Johannesburg’s Sandton. Sandton’s wealth is the direct result of it being the South African hub that connects into the global financial network, a satellite of the international hub in London, 14,000 kilometres away. That’s where I would end up, taking this photo from a skyscraper in the heart of global financial capitalism.

For my entire adult life I’ve been trying to put all of these fragmented snapshots of economic life together, trying to see the connections between the VIP back-stage areas of high finance in London and that worker in the back of the bakkie in Pinetown. It takes time to detect the edges of the multi-tiered ecology of capitalism, but today I’m starting work on designing a short course addressed to my past confused teenage self, and to everyone’s teenage selves, to help them understand the basic outlines of the system they’re walking into. I’m naming it Intro to Economic Life 101, because ‘the economy’ is not a thing, but rather a series of processes that we live, day-in day-out. The course is intended to help a person visually situate themselves in this mesh of interlocking relations, and to see how these entangled parts affect every aspect of their lives. It will also show the deep systemic problems that emerge from our system, and the different ways we might seek to change it. I’ll be rolling out the beta version of this in 10 parts to paying subscribers, who will get to see it in formation and give their input. Do sign up if you’d like to come along for the ride.

You can find the full course here. I do hope you join me!

hell yeah

what you've written, Brett, resonates strongly - the course sounds enticing. re: "I’ll be rolling out the beta version of this in 8 parts to premium subscribers . . ." i'm not seeing a category called, Premium; i see, Monthly, Annual, Patron and Free - please advise, which is premium?