Those who follow my work will know that I get deeply frustrated by the OTOMI - the One Type Of Money Illusion. People who suffer from the OTOMI speak of money as a singular blob, making no deep distinctions between its different issuers, layers and forms. We often hear about ‘the dollar’ or ‘the pound’, but in reality the dollar is an ecosystem created by multiple issuers issuing money in multiple layers in multiple forms. Pointing this out isn’t mere pedantry. It really makes a big political difference who these players are, what technologies they’re using, and what the balance of power between them is. The OTOMI prevents the public from understanding what’s at stake.

I laid out a method for breaking free from the OTOMI in my piece The Casino-Chip Society, where I used the metaphor of casino chips to help highlight the different layers of money that we use. Much like a casino privately issues chips to us when we hand them cash, banks privately issue ‘digital casino chips’ to us when we deposit cash (or when we ask for loans). Those privately-issued chips are what you see in your bank account, and what you then use for ‘cashless’ payments. Players like PayPal, in turn, will issue another layer of chips on top of that if we transfer our bank chips to them. We end up with at least three chained layers of publicly and privately-issued money, and once you get to that third layer there are literally tens of thousands of issuers of ‘dollars’ or ‘euros’ or ‘rupees’.

But, while this casino chip metaphor is useful, it has limitations. It’s good for revealing obvious relationships between money forms (like ‘I deposit Layer 1 cash at the bank and they issue me Layer 2 chips in return’), but not as good for revealing more subtle and complex background interactions between money types. In this piece I’ll lay out some further building blocks that will help us expand beyond the casino metaphor, but to do that we must first meet another illusion: the OTOPI.

The OTOMI’s shadow: The One Type of Payment Illusion

One of the classic signs that someone is suffering from the OTOMI is that they also suffer from the OTOPI - the One Type of Payment Illusion. They’ll make a distinction between the things they are paying for (groceries, train ticket, tax, interest, subscription to Spotify etc), and the form factor of the payment (was it physical or digital), but the act of payment itself is seen to be essentially uniform: it’s always just generic money moving from Party A to Party B, both of whom are assumed to be users of money.

The reality is that there are many payments in which Party B is not a user of money, but rather an issuer of money. Once you can understand this distinction, acts of money transfer become a lot more variegated, their character shifting depending on whether the interaction is happening between two or more issuers, an issuer and a user, or between users. I’m going to break the OTOPI by showing you that the apparently singular act of passing money can actually be split into at least nine different categories operating in different dimensions of our monetary system. Some of these payments create money, while others merely transfer it, and others destroy it. Some create and destroy it simultaneously.

Like a lot of my work, this account is going to be stylised, in the sense that it’s not intended to be a pedantically accurate technical account for total geeks, but is simplified in order to be useful for non-specialists. I’m going to lay out each type of payment, along with scenarios in which they occur, but before we can do that let’s sketch out three conceptual dimensions that will intersect with each other in the process.

Dimension 1: Layers of Money

My Casino-Chip Society essay broke money down into three layers, but for simplicity I’m only going to use the first two:

Layer 1 state-issued money

Layer 2 bank-issued money (‘digital casino chips’)

Dimension 2: Vertical and Horizontal Planes

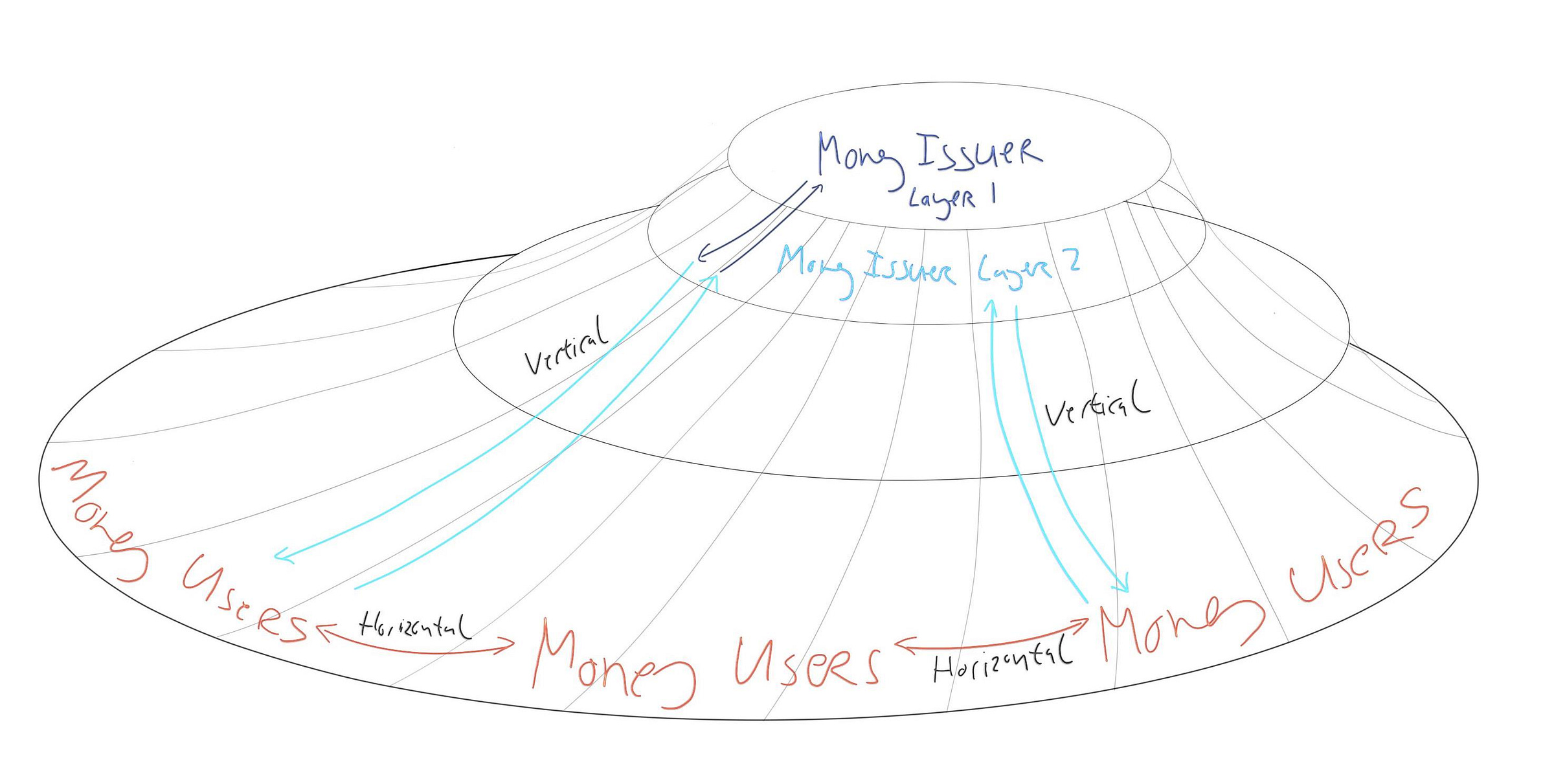

To delve deeper into money requires seeing things in 3D, and that requires vertical and horizontal planes. We’re going to split monetary payments into those that are:

Vertical: a payment between a money issuer and a money user

Horizontal: a payment between two money users

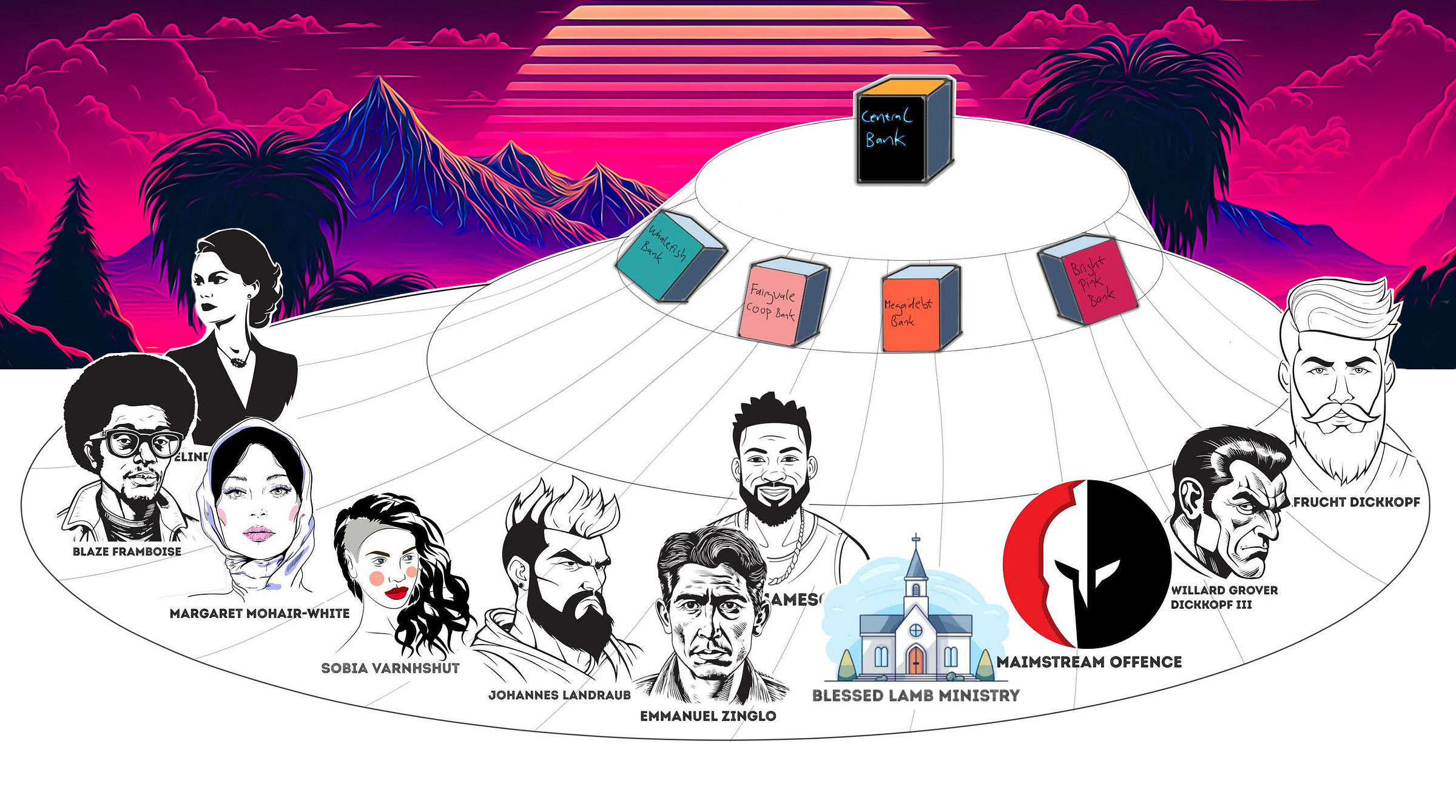

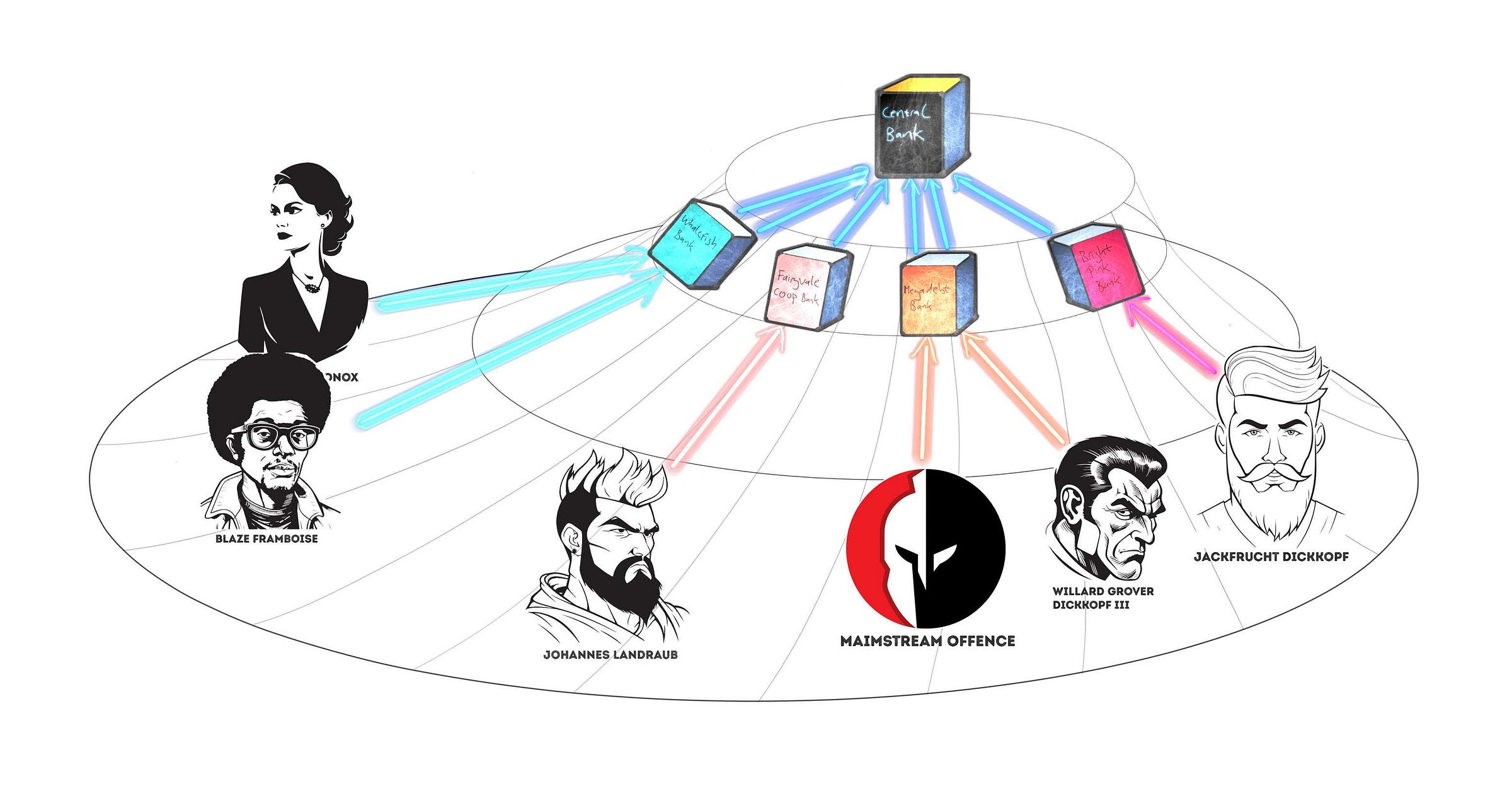

I use this spacial metaphor because it helps to convey power relations: the most important issuers of money loom ‘above’ us in society, issuing money ‘down’ to us and pulling it back up again. Ordinary folk doing commerce on the streets, by contrast, are passing money ‘horizontally’ between themselves. Check out the basic sketch above to get the vibe.

Dimension 3: Money Supply Consequences

We’re used to thinking that an act of payment transfers money, but some acts of payment create money, while others destroy it. This means payments have two sets of consequences: firstly, they act to get something for the payer, but secondly, they also have a positive, neutral or negative effect on the money supply. Here are the categories, and you’ll see that some are mirror-images of each other:

Creative issuance: new money is created through the act of issuing

Neutral issuance: new money is created, but only by rendering other money inactive

Neutral transfer: no new money is created

Complex neutral transfer: balancing sets of money are destroyed and created, leading to no new money being created on net

Neutral redemption: money is destroyed, but only by reactivating other money

Destructive redemption: money is destroyed by being redeemed

The Nine Payments

There are nine different types of payment that I’m going to showcase, each of which emerges at a different intersection of the dimensions above. Understanding each of these is technically demanding for a beginner, so I’ve illustrated them below with some lively characters and storylines that will make the learning journey slightly more fun (make sure you’re enabled images so you can see the sketches). If you’re struggling with one section, just move onto the next - it’s better to get a rough sense for all the types than to get stuck on one of them. Finally, my list is not exhaustive, and the ordering I’ve chosen is partially arbitrary. You could start from a different point to me and see where it takes you, but I’m going to start us with an act of money creation.

Payment Type 1: Government Money Creation

Scenarios

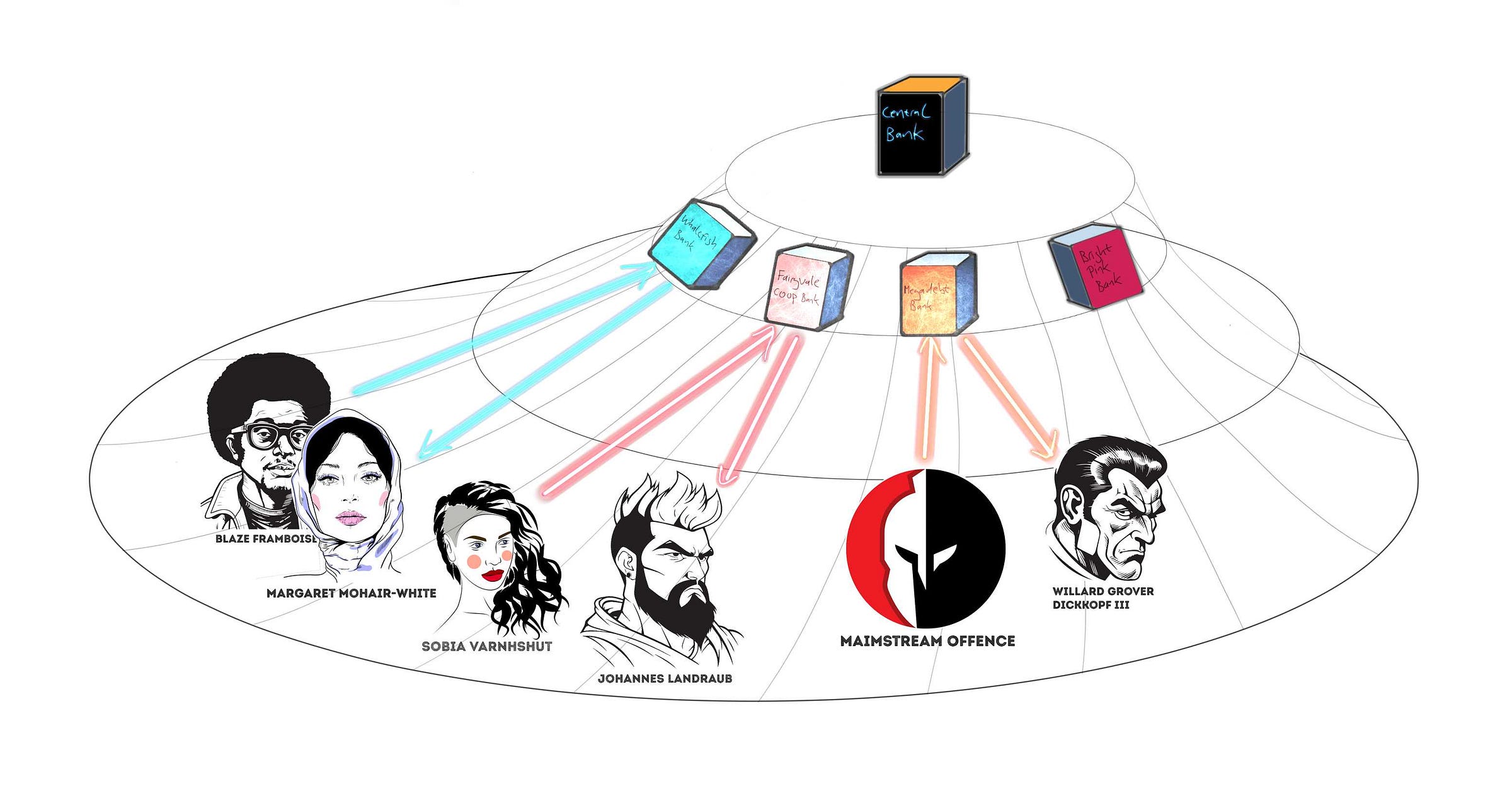

1.1: A military contractor called Maimstream Offence Inc. gets paid by the US government for delivering assassination drones to the Pentagon. The payment appears in their account at Megadebt Banking Inc.

1.2: Sobia Varnhshut is a single mum who gets a child support payment via a government welfare department. It appears in her account at Fairyvale Cooperative Bank

1.3: Blaze Framboise is a spy who has embedded themselves as a civil servant in a government department, and who receives their salary at an account at Whalefish Bank

Category

All of these are examples of Layer 1 Vertical Creative Issuance, via Layer 2 Vertical Neutral Issuance.

Description

In the scenarios above companies or people are receiving payments from the government, which turn up in their bank accounts. This is what we call ‘government spending’, and every act of government spending is an act of money creation (in countries that control their own currency at least).

To grasp this you first need to have some familiarity with how credit money works, and the quickest way to understand credit money is to grapple with the concept of ‘paying by promise’. Picture yourself getting something by issuing a promise (e.g. ‘If you help me paint my room I’ll make you dinner'). You’re getting an immediate service (painting) by issuing a promise for something in future, so - in a sense - you’re ‘paying’ for that service by issuing that promise. That promise is a liability to you because it puts you on the hook (‘I owe them a dinner later’), but an asset to the person who holds it (‘yum, I’m owed a dinner later’).

Governments do a related thing, albeit in a far more complex, obscure and large-scale form. They get immediate things (like missiles, or road building services, or healthcare for citizens), by issuing credits that we call money, which are experienced as a liability to the government but as an asset to whoever holds them.

I realise this is a pretty complex way to start, and I know for a fact that some readers will initially struggle to conceptualise what is being ‘promised’ in the case of government money issuance. That’s a specialist topic for another time, but all I’ll say for now is that it’s initially useful to see government-issued money as a credit promising you temporary freedom from your existential bondage to the state, via it’s ability to extinguish your tax debt (yeah, I know I’m glossing stuff over here, but I’m doing stylisation).

For our purposes right now, it’s more important to note that governments almost never directly issue these credits to the recipients. Rather, they issue them indirectly by paying the banking sector. To pay Maimstream, Sobia and Blaze, the government issues new Layer 1 credits into the reserve accounts of their banks (Megadebt, Fairyvale and Whalefish) at the central bank, leaving those banks to in turn credit the recipients’ accounts with newly issued Layer 2 ‘digital casino chips’ (check out the image above for a visual sense of this). In essence, the government’s Layer 1 liability ‘ripples’ like a domino through the bank into the recipient’s world as a Layer 2 asset, as follows:

Government issues new Layer 1 credits, which it experiences as a liability

Recipient’s bank receives those, experiencing them as an asset, but simultaneously must issue out Layer 2 chips to recipients, which it experiences as a liability. This means, on net, the bank’s new asset is counterbalanced by their new liability

In the recipient’s world though, they end up with new Layer 2 bank chips, which they experience as an asset

Payment Type 2: The Intra-Bank Transfer

Scenarios

2.1: Maimfactory initiates a bank transfer into the account of their CEO - Willard Grover Dickkopf III - as a bonus for securing a smart-grenade deal with the Saudi government. Willard also banks with Megadebt Bank

2.2: Sobia pays rent to her landlord, a frustrated wannabe MMA fighter called Johannes Landraub, who also happens to bank at her bank

2.3: Blaze is on a Tinder date, and makes a contactless payment at a bougie cocktail bar, whose owner - Margaret Mohair-White - also banks with Whalefish

Category

These are all examples of Layer 2 Horizontal Neutral Transfer.

Description

In the scenarios above, payers are initiating a transfer of Layer 2 ‘digital casino chips’ to a recipient that happens to bank at their bank. This means that previously issued Layer 2 money is just getting reshuffled between people. This is pretty straightforward for the bank, because the payment is a simple internal accounting operation for them. They simply take Layer 2 chips from one account holder and give them to another (in a digital system this is a simple act of editing, like switching numbers between two adjacent cells on an Excel spreadsheet). The asset and liability breakdown is pretty straightforward:

One account holder has their chips go down, while another has their chips go up. On net, there’s no change in the overall level of chips outstanding

The bank is indifferent to whoever holds their Layer 2 chips, much like a casino doesn’t care when one punter loses chips to another, and there’s no change to the bank’s overall liability

Payment Type 3: ‘Getting a Loan’

Scenarios

3.1: Willard and his chief finance officer successfully secure a new 10-year loan for Maimstream Offence from Megadebt Bank. Maimstream’s account at Megadebt is credited with $50 million

3.2: Johannes Landraub gets a new mortgage to expand his rental property empire. He signs a loan agreement and the bank credits his account with one million dollars

3.3: Margaret Mohair-White has been spending beyond her means on vintage absinthes, but she’s got a big overdraft with her bank that automatically loans her money when she dips below zero

Category

These are examples of Layer 2 Vertical Creative Issuance.

Description

In the scenarios above, the recipients are obtaining bank loans, but when a bank is ‘loaning money’ it is simply issuing new Layer 2 digital chips into the recipient’s account. This is called ‘credit creation of money’. To delve deeper into this, see my Emotional Guide to ‘Fractional Reserve Banking’, but for now let’s look at the liability and asset side of this:

The bank issues out new liabilities in the form of Layer 2 digital casino chips

The recipient experiences those as new assets in their account

The bank isn’t a charity though: in exchange for issuing those new chips, they’ve extracted back from the recipient a legal promise to hand back a greater quantity of Layer 1 money over time (well… there’s nuances to this, but we’ll discover those later). The bank experiences this loan contract as an asset, and one that’s worth more than the new liabilities they’ve issued (albeit this asset carries risks). The bank is essentially issuing Layer 2 money to harvest or ‘buy’ loan contracts that will attract Layer 1 money to them over time

The recipient, on the other hand, experiences that loan contract as a liability that will gradually extract more back from them in the long term - via interest payments - than what they’re getting in the short-term

It’s very important to note that no government-issued money is being used in this process. In old-school texts about banking they always say stuff like ‘the bank takes money that was deposited into it and lends it out’, but this is very wrong: the act of ‘lending’ is simply the act of a bank privately issuing out new ‘digital casino chips’. Bear in mind, however, that once a recipient has those chips, they can demand to redeem or transfer them, and the bank has to be able to manage those demands.

Payment Type 4: The Inter-Bank Transfer

Scenarios

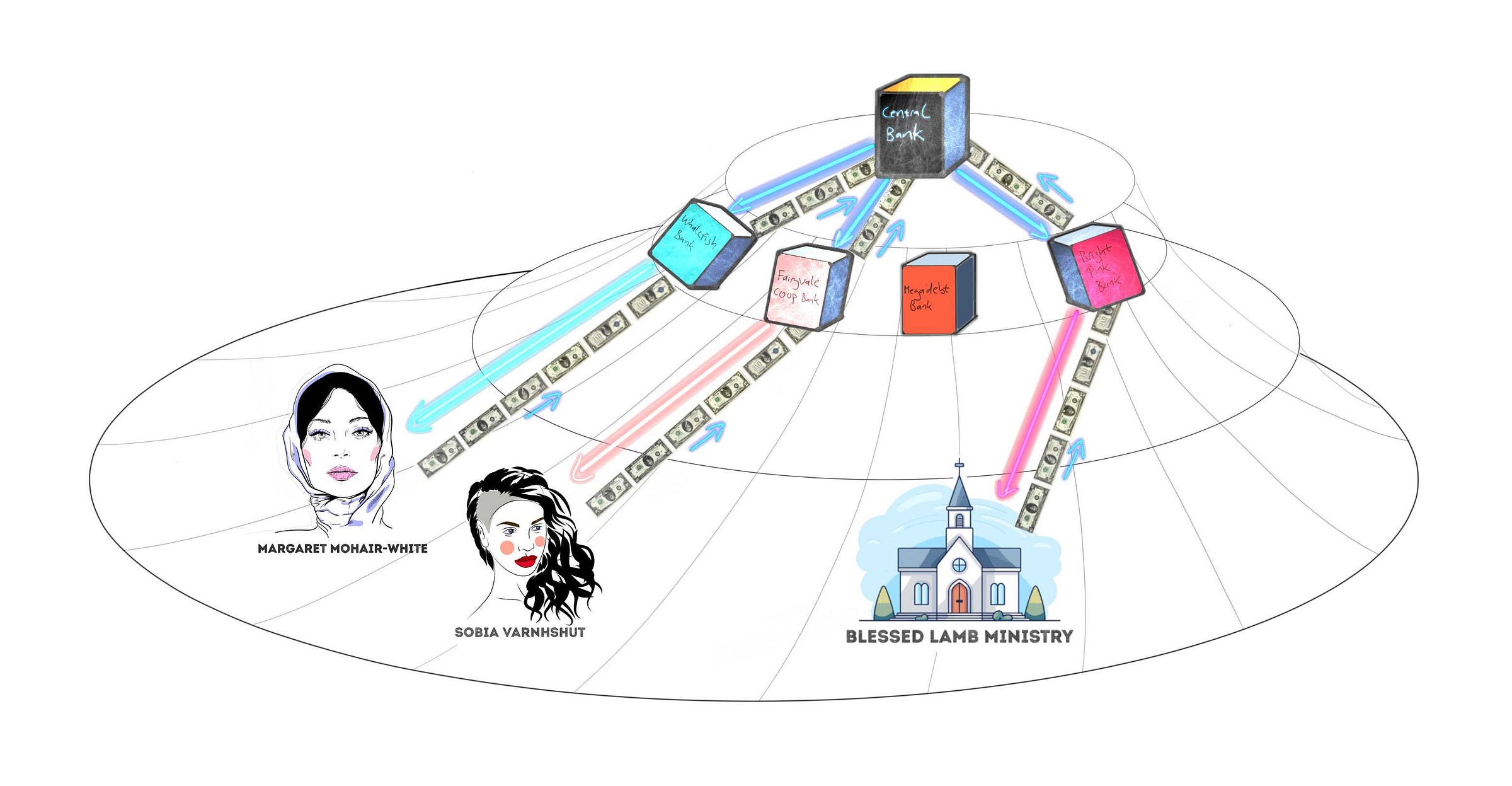

4.1: Maimstream Offence, under the instruction of Willard Grover Dickkopf III, makes a transfer to a tech company called MinRep, apparently to fund a research project on military facial recognition tech for drones, but the company is actually a front for Willard’s playboy son, Jackfrucht Dickkopf, who banks with a digital-only neo-bank called Bright Pink

4.2: Johannes Landraub might have been issued 1 million dollars in digital casino chips by his bank, but those won’t stay in his account for long, because they were granted for the purposes of buying a house from a retired sculptor called Melinda Oldonox, who banks with Whalefish. A transfer takes place and her account gets credited as Johannes takes title of her old house

4.3: Margaret Mohair-White is getting vexed by the fact that homeless people are sleeping in the doorway of her cocktail bar. She makes a bank transfer to a craftsman called Emmanuel Zinglo, after he designs and installs anti-homeless spikes for her (albeit tastefully crafted in the form of art nouveau hedgehogs to fit in with the bar’s aesthetics). He doesn’t feel good about it, but he’s low on work, so accepts the payment into his account at Fairyvale

Category

These are examples of Layer 2 Horizontal Complex Neutral Transfer.

Description

In all the scenarios above, someone is trying to use their bank-issued Layer 2 digital casino chips to pay someone else who banks with another bank. At face value, that’s a bit like trying to use the chips of Caeser’s Palace Casino in Nero’s Palace Casino. Look at the image above: how do you get Megadebt-issued chips to ‘jump’ from Maimstream’s account at Megadebt Bank to Jackfrucht’s account at Bright Pink Bank? How do ‘inter-bank’ transfers actually happen?

The most important thing to note is that they don’t ‘jump across’ at all. What actually happens is that the first bank retracts Layer 2 chips from the payer, passes Layer 1 reserves to the other bank, and gets that other bank to issue new Layer 2 chips to the recipient. Unlike Payment Type 1 above, which involved a vertical ‘ripple’, this one involves a horizontal ripple. Let’s illustrate it with the case of Margaret and Emmanuel (see if you can follow the path in the image above):

Whalefish Bank retracts Layer 2 chips from Margaret Mohair-White, so her assets go down

Given that Whalefish has taken their chips back, their liabilities go down, but the bank’s assets also go down, because it must pass Layer 1 reserves to Fairyvale Bank

Fairyvale will see its Layer 1 reserves go up, so their assets go up, but they have to issue out new Layer 2 chips to Emmanuel, so their liabilities also go up

Emmanuel receives these new Layer 2 chips, so his assets go up

In any single inter-bank transfer, the two banks end up with the changes in their assets being offset by an equal change to their liabilities, while the two end users of their chips end up with offsetting increases and decreases of assets. The individual situations of each player might have changed, but at a systemic level nothing has changed in the money supply: when viewed as a unit, the two banks have the same amount of chip liabilities outstanding, and the two recipients collectively have the same amount of chip assets, even if there has been a relative reshuffling of these between the players via the horizontal ripples.

The final thing to note is that banks very seldom process these inter-bank interactions individually. Normally what they do is collect them all up into bundles and settle with each later via big ‘multilateral netting’ systems: Notice in the image above that when Johannes pays Melinda reserves must move from Fairyvale to Whalefish, but when Margaret pays Emmanuel they must move in the opposite direction from Whalefish to Fairyvale. In a netting system, those movements would be offset against each other. In fact, with this type of netting in place, large amounts of Layer 2 chips can be reshuffled around the payments system while much smaller amounts of Layer 1 reserves move between banks.

If you’re finding this useful please give the piece a like. I put loads of effort into these pieces and getting a thumbs up helps me to gauge whether folks are getting something from it!

Payment Type 5: The ATM Withdrawal

Scenarios

5.1: Jackfrucht Dickkopf withdraws $5000 in cash. He wants to visit a sex worker who he’s fallen in love with, and who he doesn’t want his wife to know about it

5.2: Melinda Oldonox withdraws $1000 to give as a short-term loan to her friend Margaret Mohair-White, who is struggling after maxing out her overdraft to pay for art nouveau hedgehogs

5.3: Emmanuel Zinglo withdraws cash for his church tithe collection. He wants to expunge his feeling of guilt for building anti-homeless spikes for Margaret

Category

All of these are examples of Neutral Redemption, but it happens via Layer 2 Vertical Redemption and Layer 1 Vertical Transfer.

Description

We don’t normally think of an ATM withdrawal as being a ‘payment’, but it’s a type of payment in the sense that Layer 2 chips moves from you back to the bank that issued them, while Layer 1 money moves from the bank to you (note: for the purposes of this section, I’m going to assume you’re visiting your own bank’s ATM - it gets more complex if you visit an ATM controlled by another bank).

The act of going to an ATM is basically like turning up at a casino counter and demanding to cash your chips. As mentioned, however, my casino chip metaphor has limitations, and you might have already started to notice some of them. For example, in Payment 1 we saw that the actual act of government money creation started with the state issuing digital credits to the banking sector, and then getting the banking sector to issue chips to us (rather than the state issuing out cash to us and then us depositing that cash into banks to get chips, which would be the more ‘casino-like’ scenario).

To get the full picture of what’s going on, you need a basic grasp of the two different forms of Layer 1 money: when a government issues out credits in digital form to the banking sector it gets called ‘reserves’, but when it does it in physical form it gets called cash. They are both Layer 1 money, but we in the public don’t have access to reserves. So, if the state is issuing Layer 1 money primarily by issuing reserves to banks, how do we end up with cash in our hands?

Well, at a systemic level, cash is ‘released’ when people and companies asks their banks to ask the central bank to swap digital reserves into cash, which then gets pushed out into the world via ATMs and branches (a process that also leads to the banking sector collectively having to pull chips out of society, which is also a process in which they lose power). My piece What Tron teaches us about Cashless Society provides a different metaphor set to help you understand this, but let’s look at the asset-liability chain to help clarify (and check out the image above for a visual representation of this):

Firstly, a bank must prepare for the possibility that someone will demand cash by stocking up their ATMs and branches. They do this by asking the central bank to switch out some of their Layer 1 digital reserves for Layer 1 physical cash instead. The bank’s Layer 1 assets end up the same, but the form factor has changed (e.g. imagine Fairyvale has $10 billion in digital reserves, and $0 in cash, and then gets the central bank to rearrange that to $9 billion in digital reserves and $1 billion in cash)

When Emmanuel turns up at the ATM and requests cash, the bank retracts Layer 2 chips from him - which means the bank’s liabilities go down - but then has to hand over Layer 1 cash to him, which means the bank’s assets go down too

Emmanuel loses Layer 2 chips but gains Layer 1 cash, which means his assets stay at the same overall level

Notice that the bank reduces assets and liabilities simultaneously, so the act of us swapping chips for cash is theoretically ‘neutral’ to them, but in reality what we’ve done is swap allegiance from one money issuer to another. We have ‘activated’ the Layer 1 cash by deactivating - well actually destroying - the Layer 2 bank chips, and that represents a shift in power between two money issuers. Our situation largely remains the same, but the bank is now losing the data and fees it would have previously been getting had you simply stuck with using their chips.

As we saw in Payment 1, the banks are - in one sense - agents of the state, allowing its Layer 1 promises to ripple through them to us via their Layer 2 chips, but those chips in turn become a form of money that competes with any form of state money that we can directly hold, like cash. One of the often-missed points in debates about cashless society is that the banking sector does not issue cash, but is a gatekeeper to it. This means they are in a position to slowly nudge people away from it by doing stuff like closing down branches and ATMs, a process that slowly locks people into dependence upon their digital casino chips.

Know anyone else who would find this piece useful? Please share it with others!

Payment Type 6: The Cash Payment

Scenarios

6.1: Jackfrucht Dickkopf pays his sex worker lover Jamae Jackson $5000 in cash to spend the weekend with him, pretending to be on a work trip so that he can hide from his wife and authoritarian father. Jamae later passes half the cash to his half-sister and best friend Sobia, who needs support covering her rent

6.2: Melinda Oldonox slides an envelope with $1000 in cash to Margaret as they sip absinthe martinis

6.3: Emmanuel Zinglo stuffs $200 into the collection pot of his church, Blessed Lamb Ministry, whispering ‘forgive me father. Please use this to feed the homeless’

Category

All of these are examples of Layer 1 Horizontal Neutral Transfer.

Description

While its tricky to understand what goes on behind the scenes with an ATM withdrawal, it’s super easy to understand what happens once you get the cash out. In the scenarios above one person is handing government-issued credits in physical form to another. No banks are involved. End of story. (PS. if you want to see why cash payments like this must be defended, check out my Luddite’s Guide to Defending Cash).

Payment Type 7: Depositing Cash

Scenarios

7.1: Sobia Varnhshut needs to prepare for her next rent payment, so deposits the cash into her bank

7.2: Margaret has debts to pay, so she deposits the cash into Whalefish

7.3: The church wants to convert its cash into digital chips that can be used to buy shares in the stockmarket (via an index fund that happens to invest in Maimstream Offence), so they deposit the cash into their account at Bright Pink

Category

These are all examples of Neutral Issuance, but it happens via Layer 2 Vertical Issuance and Layer 1 Vertical Transfer.

Description

In all the scenarios above people are handing over Layer 1 physical money to their banks, and getting Layer 2 digital chips in return. This is actually the payment type where my casino metaphor works best, because it pretty much replicates that old-school casino situation where you turn up at the counter, hand over cash and get chips in return.

The issuing out of digital chips by banks is an act of Layer 2 money creation, but in this case it’s done by surrendering Layer 1 money to them (contrast this to Payment 3, where banks issue out new Layer 2 money without any movement of Layer 1 money). This process is also the direct mirror image of Payment 5, so to complete the picture I have drawn the banks handing over their newly obtained cash to the central bank to exchange for digital reserves instead (a process that takes cash out of circulation).

The banks like this situation, because you’ve essentially surrendered a competing form of money to their control, and resume your dependence upon their digital chips. In their ideal world, the banks vacuum all cash out of society and have everyone totally structurally and mentally captured by their systems, with all shops refusing cash and everyone forgetting that it once was normal. To build this level of cultural hegemony, however, takes time, and their progress on it is patchy (although in places like London, for example, they have made huge gains by almost totally capturing the middle classes).

Fast-forward

I’m going to finish with two last forms of payment, but before we do that let’s push fast-forward on our mini-economy and assume that our cast of characters make and receive a whole series of payments. In particular, let’s assume that Maimstream, Johannes and Margaret receive a bunch of Type 4 payments. This, as we saw above, will lead to their banks getting new Layer 1 reserves while issuing out new Layer 2 chips to them.

Payment Type 8: Repaying a Loan

Scenarios

8.1: Maimstream owes interest on its 10-year loan from Megadebt, so makes a payment

8.2: Johannes makes a mortgage payment to Fairyvale

8.3: Margaret pays off her Whalefish overdraft

Category

These are all examples of Layer 2 Vertical Destructive Redemption

Description

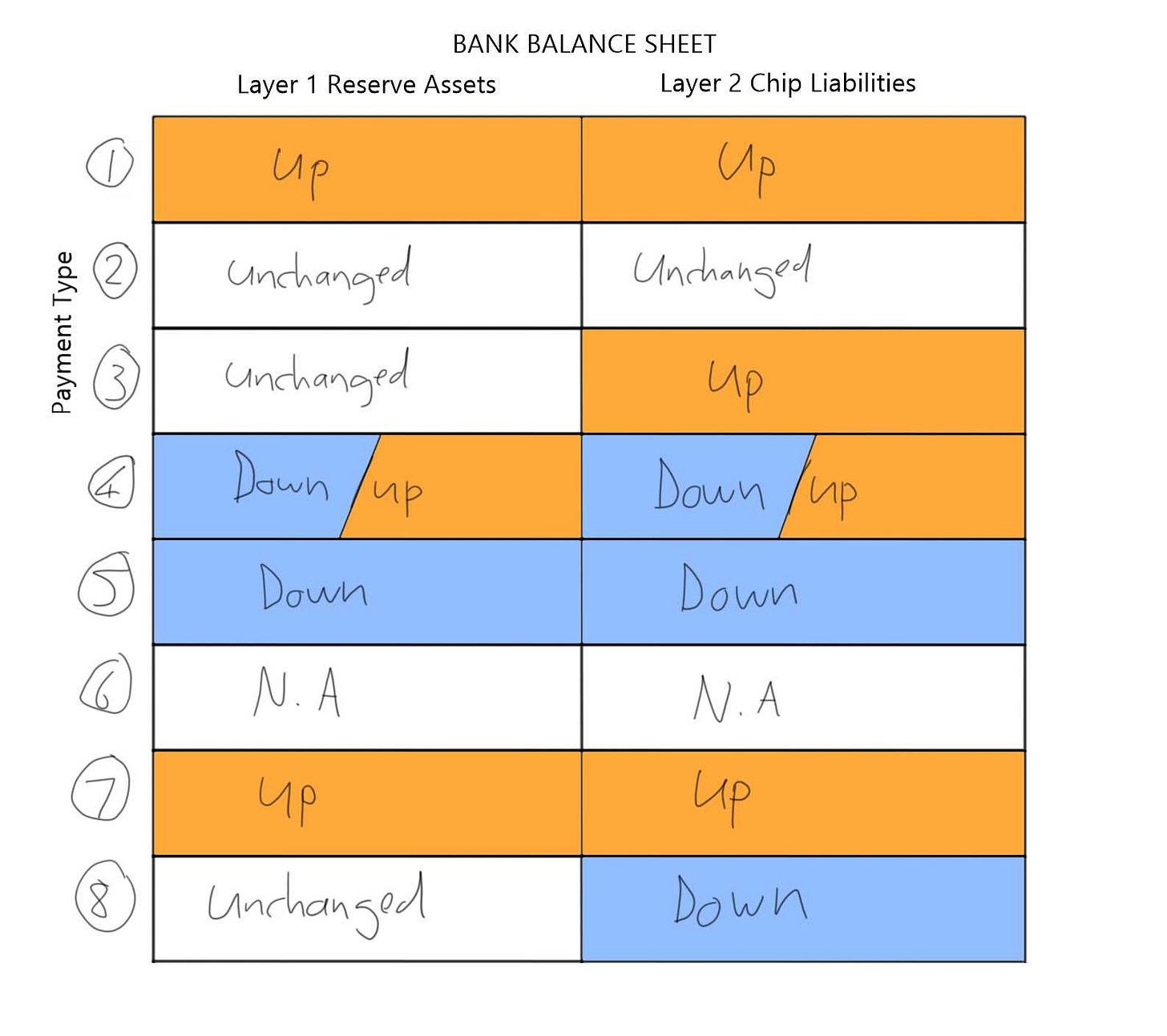

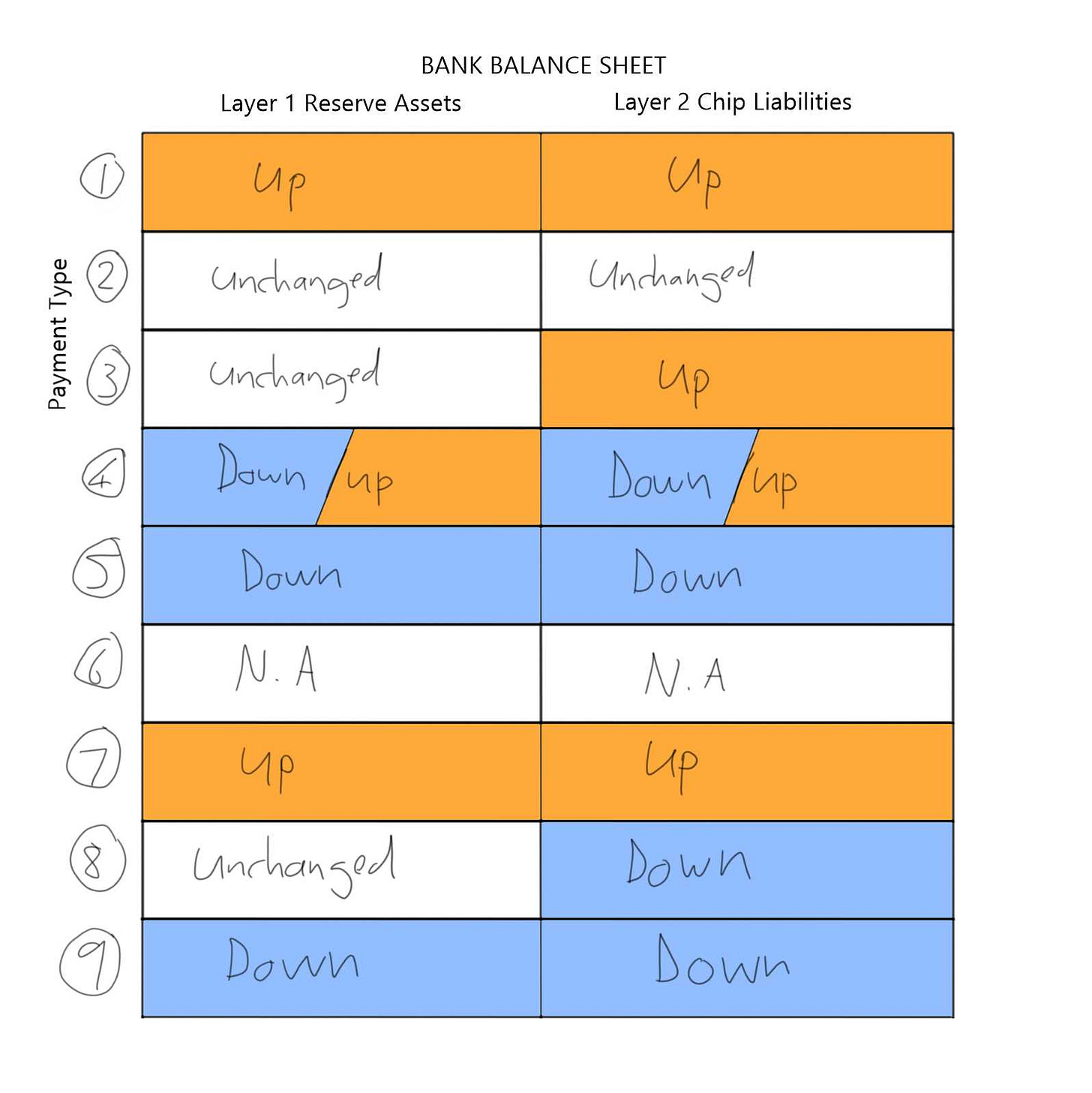

All the examples above are mirror images of the situation described in Payment 3, where new Layer 2 chips were handed out by banks to people who asked for loans. In Payment 8 people are handing those back in order to ‘repay’ their loans, or interest on their loans. This seemingly simple payment is one of the most fascinating things to explore in banking, and we can only scratch the surface here, but to understand what’s happening you have to pay attention how all the other forms of payment affect a bank’s balance sheet. I’ve summed it up with this table:

You’ll note that only two of these - Payment 3 and 8 - are unsymmetrical. Credit creation of money (Payment 3) occurs when banks expand their Layer 2 chips without expanding their reserves, but credit destruction of money (Payment 8) is the opposite: it occurs when banks destroy Layer 2 chips without reducing their reserves. The crucial question for any bank is whether they can destroy more Layer 2 chips in the latter process than they created in the former, because - if so - it actually means they gain Layer 1 reserves.

To make this slightly less abstract, consider the case of Johannes. When Fairyvale bank granted him $1 million in chips (Payment 3), their chip liabilities went up without their reserves going up, but in Payment 4 their chip liabilities and reserve assets went down simultaneously as Johannes initiated a transfer to Melinda. Johannes, however, is a landlord getting rent transfers back from people - including people who may bank at different banks - so this will manifest in Fairyvale’s world as a simultaneous increase in their reserve assets and chip liabilities. Given that there’s interest attached to the loan, Johannes must accumulate more Layer 2 chips (via, for example, Payment types 2 or 4) than the bank originally granted him, in order to pay back over time. This means that over time (and assuming that Johannes doesn’t go bankrupt) the bank will accumulate more Layer 1 reserves via those transfers than it originally lost when he paid for the house, after which they’ll cancel out Johannes’ claim upon those reserves by getting him to hand back a greater number of Layer 2 chips than he was first granted (aka ‘interest’).

This is a highly simplified description, but it’s a useful start to understand what ‘repaying’ a loan actually means. In a bank balance sheet, it will manifest as an increase in their equity: their reserve assets stay the same while their liabilities - external claims against the assets - decrease, leaving them with the surplus. One of the dark arts of banking is to issue out Layer 2 money to harvest interest-bearing loan contracts that will create a monetary pressure gradient that slowly pulls Layer 1 money to the bank. Whew, now onto our last payment type.

Payment Type 9: Paying the Government

Scenarios

9.1: Melinda pays capital gains tax on the house she sold to Johannes

9.2: It’s discovered that Blaze is a spy. He flees the country in a hovercraft, but not before the authorities seize his bank account and claw back all his salary

9.3: Johannes takes part in a privatisation programme where old government-owned social housing is sold to private landlords

9.4: Maimfactory manages their finances by buying short-term government bonds

9.5: Willard and Jackfrucht are fined by the government for a fraudulent transaction in which Willard siphoned off Maimstream funds to his son for non-existent work

Category

These are examples of Layer 1 Vertical Destructive Redemption, via Layer 2 Vertical Neutral Redemption.

Description

In all these cases, the protagonist is paying the government (or being forced to pay), but doing so via the banking sector. At first glance, this looks like they’re using bank-issued chips to pay the state, but in reality they’re not. Rather, they’re handing back bank-issued chips to the banking sector in order to get the banking sector to pay the government using Layer 1 digital reserves, which is a mirror image of what we saw in Payment 1. In the bank’s world, their liabilities go down as they retract digital chips, but their reserve assets go down as they hand reserves to the government’s account at the central bank, a process that actually leads to the destruction of Layer 1 money. Here’s our full set of payments from a bank’s perspective:

People who are well-versed in MMT (Modern Monetary Theory), are used to this idea that taxation, fines and fees paid to the government, and even government ‘borrowing’ (in which people pay the government for financial instruments) result in the destruction of Layer 1 money. Remember folks, if somebody hands me back a promise I’ve issued, the promise no longer exists. Similarly, when someone hands back a credit, IOU or other promissory instrument to its issuer, it gets destroyed.

I’ve taken you through the whole cycle in 9 steps, but of course there are many nuances I’ve missed out, and other categories too. For example, there’s a lot of talk right now about a hypothetical new form of Layer 1 digital horizontal neutral transfer, and to learn about it see my Zen and the Art of CBDC Analysis. I’ve also totally glossed over international payments, which involve interactions between banks that are part of different currency ecosystems under different central banks. As mentioned, I’ve also left out all Layer 3 forms of money, and the entire shadowbanking sector (which you might think of as a kind of Layer 4 realm). There’s also a whole range of innovative forms of issuance on the horizontal plane when you get into the realm of alternative currencies (for more on that see Zero is the Future of Money). These are all exciting topics that can be explored in future.

Thanks for your time, and if you found this useful please do leave a comment and share the piece.

hey Brett and any of your Berliner readers, this isn't a direct comment exactly, but to let people know that the 3rd European Modern Monetary Theory Conference 2023 in Berlin starts 2mrw. ( Sep 9-11 ) I'm still learning about MMT-ers, but have heard from friends that some of these speakers are very good at explaining the money systems ( but not necessarily good in the politics of building the alternatives ), and would be very curious how you would analyze their conference with the theme: Navigating the Polycrisis: A conference on European Macroeconomics. We might try and write up a small XLterrestrials analysis ( https://xlterrestrials.substack.com/ ), but we won't be able to attend all of it... maybe see you there !

This piece really helps to fill out & cement my existing understanding of payments & the money layers. I appreciate your flair for explanation & use of metaphors—thanks for sharing your knowledge!

I have a semi-related question: How do bank interest profits manifest?—as additional reserves? or does the bank maintain internal "cash accounts" where it stashes its profits?