How the 'Functions of Money' blind us to the Structure of Money

And how this leaves us confused, disorientated and exploitable

When it comes to most useful things, we intuitively know that their structure precedes - or gives rise to - their functions. For example, your computer has a structure that enables you to read this article. Money too has a structure that enables certain functions to exist, but, when asked to describe it, many people will describe what money does, rather than describing its structure. I’m going to show why this is the case, and why it’s major source of disorientating confusion that deeply hampers our ability to understand our world.

The problem of functions without structures

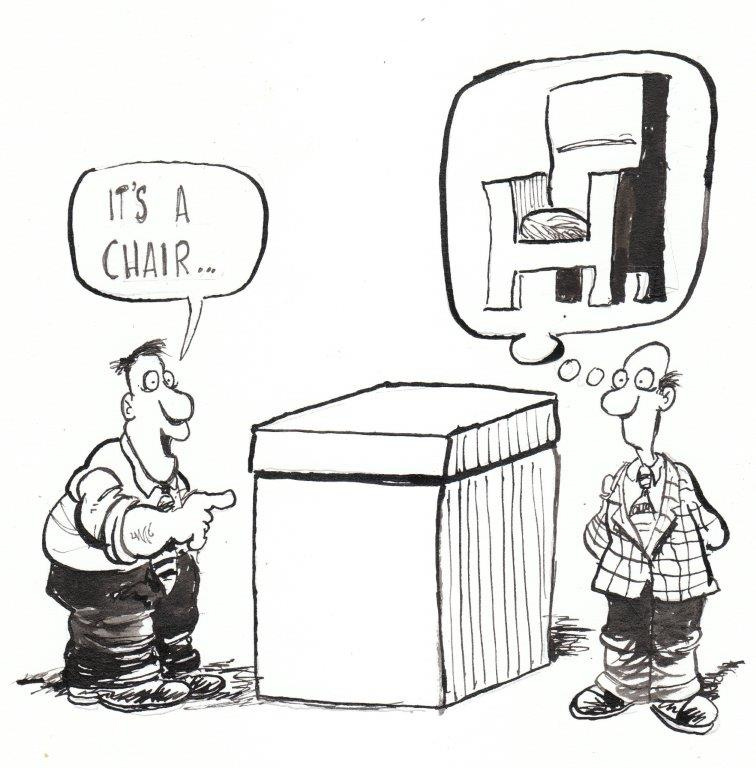

Let me use a thought-experiment to illustrate what happens when functions and structures get mixed up. Imagine a box with something inside it. Your friend says ‘it’s a chair’…

Upon hearing this, your brain conjures a structural image of a chair, and that image comes along with an intuitive notion of its functions. The structural image might vary from person to person, but it’s probably going to consist of a solid horizontal square surface set upon sturdy vertical legs with a vertical backrest. The functional definitions might be ‘thing for sitting on’, and ‘thing for standing on to reach high shelf’.

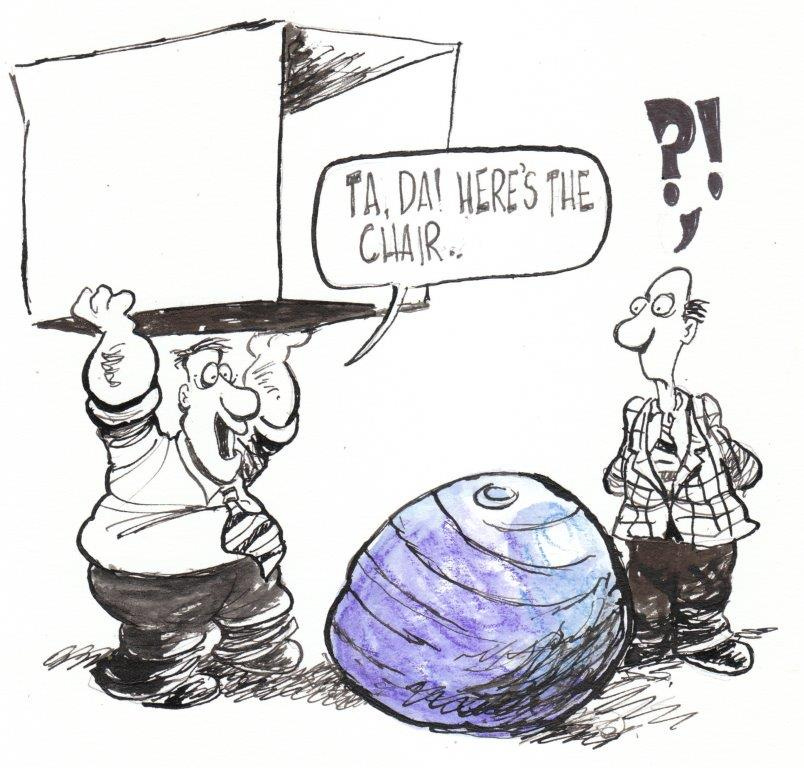

Imagine, however, your friend opens the box and reveals a different structure to the one you were expecting…

Rather than a solid construction, he reveals a bouncy, soft, spherical structure made of plastic and filled with air. This is the structural image that normally goes along with the word ‘exercise ball’ (sometimes called Yoga ball, or Pilates ball), and this ball is normally used for doing ab exercises and Pilates, but it’s also a favourite for kids to bounce on whilst playing. Some people also sit on them occasionally.

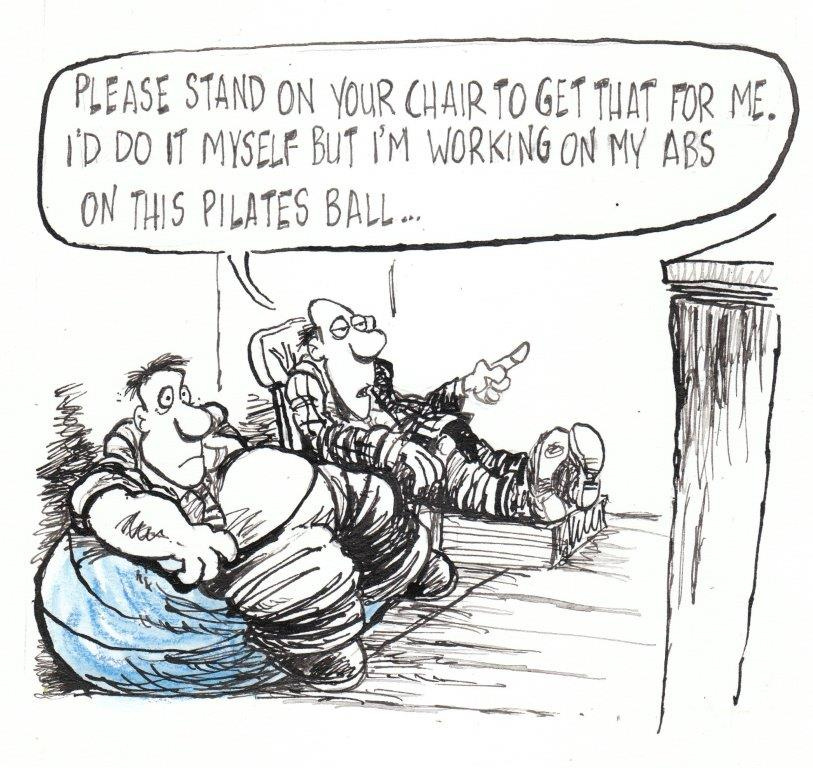

A bit later you’re slouching on an actual chair in the lounge while your friend sits on his ball ‘chair’. You point to a high shelf and say…

What’s going on here? Well, almost all of our definitions for useful objects are a composite of both the structural and functional, and it’s only through viewing both simultaneously that we make sense of a word. Nevertheless, objects with entirely different structures can share a narrow zone of functional overlap. If you ignore their structures, and focus solely upon their narrow common function, whilst also ignoring all those functions they do not share, you can briefly assert that they are ‘the same thing’.

This is how the man above originally managed to call a ball ‘a chair’, but it allows his friend to get revenge by calling upon a different function normally associated with a chair, but not associated with a ball.

Most people only do this ‘function-to-multiple-structure’ blending when joking (for example, a woman sits on her lover and says, ‘what a sexy chair I have’), but if you insist on doing it seriously it causes language to degrade. If I confined the definition of ‘chair’ to the single functional description of ‘thing you can sit on’ then the term would have to be applied to thousands - even millions - of objects. I can sit on the hood of my car, the roof of my house, a rock on top of a mountain, a guitar amplifier, and even a slackline. The entire earth becomes ‘a chair’.

By giving all of these things the same noun, their separate structures and diverse capacities are invisibilised. If this happened, the term ‘chair’ would also generate no structural image in your head. Rather, you’d just see vague blank space.

The implication is this: if you can only describe something’s function without being able to describe its structure, you’re in a realm of vagueness where meaning can collapse.

How money’s structure is invisibilized by its ‘functions’

So here’s a test to run. Ask a friend what structural image they see when they hear the noun ‘money’. Their task is to draw the structure of money, which precedes the imagined functions of money. Ask them to draw it in this box…

I predict that, nine times out of ten, the image the person will imagine consists mostly of monetary artefacts like cash tokens, numbers in bank accounts, numbers on apps, or other numbered objects, whether digital or physical. One way to check the dominant structural image of money is to type the term into a Google image search. Here it is…

Do you see a ‘structure’ here? No. What we are seeing here is best described as one part of the surface layer of a much larger structure. It’s true that there are physical money tokens that appear before us in the world, but they only work because they’re integrated into a huge system that activates them.

Showing images of cash tokens is like showing a ghostly sketch of 5% of a structure (or perhaps like decorating the border of the white rectangle where the image of money was supposed to be drawn). It’s at best a partial surface appearance, but this is where many people’s image of the ‘structure of money’ stops.

What happens if I then ask them how this imagined structure works? Well, given that their structural image consists of flimsy objects with numbers, they’re going to face an existential dilemma when trying to reconcile that with the de facto power they experience money having on a daily basis. It’s easy to see how a chair holds you up by looking at its full structure, but not very easy to see how money holds an economy up by looking at a fragment of it structure.

Here’s a very good example showing someone having this exact existential dilemma. It went viral on TikTok, and it’s worth watching because it shows them struggling to make sense of surface-level objects that make little sense unless seen within a much bigger structure. Given that they are not able to find an explanation for the power of the objects in the objects themselves, they come to the conclusion that somehow we must have ‘made up’ their power, as if money tokens were like Peter Pans held up through the power of imagination.

This idea of money being some kind of imaginary system residing in our heads - rather than being a dense network structure that literally engulfs us - is extremely common, and is found across the political spectrum. Much like I might imagine all manner of mysterious things swimming below the surface of a dark lake, the blank space where the structure of money should be is easy to fill up with emotional tumult, vagueness, and scrambled statements. It’s a world in which some people glimpse distant central banks shrouded in mist, whilst others assert that ‘money isn’t real’, and that it is ‘based on belief’.

Remember that functions without clear structures are a sure-fire way to generate a feeling of mysticism, and this abounds when it comes to money, so why is it that we struggle to see the structure? The first reason is obvious: it’s a very large structure, and its sheer size renders it invisible to a small-scale human being. We are immersed in it to the point where we cannot get enough distance from it to see it.

There is, however, a second reason, related to the first. Where does a person who is struggling to see the structure of money turn to for help? Where do people go to learn about money? Many people believe that to learn about money they should pick up an economics textbook. I often hear people saying, ‘I don’t really understand money, I’m not an economist’, as if being an economist would open their eyes to the monetary web around us. Picking up an economics textbook, however, is probably the worst thing they can do, because using standard economics for monetary understanding is like using novocaine to reach enlightenment: it might help dull the pain of reality, but leave you numb to it in the process.

Why do I say this? Well, standard economics textbooks specialise in drawing our attention away from the structure of money, by focusing it instead upon vague ‘functions of money’, to the point where many people seem to believe that the latter is the former. For example, when asked for a definition of money, it’s common for those who have studied at universities to quote the economics mantra of ‘money is a store of value, medium of exchange, and unit of account’, as if these were structural descriptions of the monetary system.

But they’re not. Those are secondary properties that emerge from a primary structure, and the fixation upon them acts like a form of blindness. They’re not even very good descriptions of the secondary properties either, and some - like ‘store of value’ - are actually partly metaphoric rather than real. Economics doesn’t help us to see money. It helps us to ignore it.

When writing this piece, I went through two economics textbooks on my bookshelf to confirm this. Both followed the very common practice of describing money indirectly through a tick-box exercise: rather than saying “here is the structure of money. It does A, B, and C”, they say “anything that does A, B and C is money”. It’s a way of eluding to the structure without ever naming it, a bit like describing a chair as ‘anything that enables you to sit on it, and also to stand on it’.

Filling in the hollow image of money

Give that mainstream economics offers at best a vague and evasive explanatory framework for money, people are either left to work out the structure through everyday experience, or they are left to search for it in places like YouTube, where various critics will offer explanations for ‘how money really works’.

Unfortunately, many of these supposed non-conformists are just as blinded by functional definitions as economists are, but, having partially glimpsed some of the more obvious parts of the structure (like central banks), they then fuse a straw man version of the latter with the former. This creates conspiratorial statements, like ‘central banks have conned us into believing in money which isn’t real!’

This is just a variation on the aforementioned ‘money is just belief’ idea, which emerges if you only look at the surface of the structure of money. The conspiracy variation just asserts that the source of the belief emerges from some act of deceit by a powerful party, rather than by some social consensus, but both versions are united in presenting money as being held up through some kind of mental trickery, rather than by an actual structure.

This doesn’t leave the public in a very good position. The chief contenders to fill in the blank space where the structure of money should be are economists with no structural images, and conspiracy theorists with straw man images. You get to pick from mainstream denialism or non-mainstream crankery.

This gives us a clear mission though.

Firstly, we must start to draw the structure, so that every time the word ‘money’ is uttered, a clear and full structural image appears. In this newsletter I have already begun that process, but we have a long way to go before the full structure reveals itself

Secondly, we need not agree exactly on what the structure looks like, but we do need to agree that it should be foregrounded. This will be a major step forward from the current status quo, which simply refuses to foreground it

Thirdly, we must be able to make a clear distinction between the individual experience of money - the everyday feeling of using money tokens at a street level - and the hidden structure which transcends that. Much like we experience the sun as a thing that ‘rises’ rather than something that stays fixed while the earth turns, there is a phenomenological realm of money which can differ from the reality of its structure, and - sometimes - the vague functional definitions can get by in this realm. When it comes to the politics of money, however, it is a downright deadly to stay in that realm

It is also damaging to stay in that realm when attempting to design alternative money systems. There are many pseudo-challengers to the current monetary regime, many of which exploit the vagueness of functional definitions of money to get away with presenting themselves as solutions. More on this to come.

Brett, you have done some pretty amazing things... This is at the top. This is such a special piece.

Hi Brett

Brilliant by putting the finger on the wound! I am completely with you. The functions of the money in the textbooks are relicts from 18th/19th century thinkers who tried in a physical sciences approach to describe money as a phenomenal entity. This outdated view is completely misleading us today. Time to look closer and go to a structural view!

Waiting for your next consciousness newsletter....