The Algorithmic Holiday

A proposal for pushing pause on the pressure of the attention economy

Paying subscribers can access the audio version here! (16 minutes). Also, I’m going to be pushing pause on payments at the end of today, so your paid subscriptions will be frozen in time until I return to full-time Substacking in a few weeks (for those on annual subscriptions, this time doesn’t count towards the year, so your subscription extends)

The Attention Economy is also a Gig Economy, and for all of us who operate within it, this has serious implications for our ability to take holidays. I’d like to offer an explanation, and one solution. Firstly, some definitions:

The Attention Economy: a sector of the economy in which media is produced by ‘content creators’ to absorb peoples’ finite attention. There’s only so many hours in a day, and only so much capacity in each person’s mind and body to take in this ‘content’

The Gig Economy: this isn’t really an economic sector, so much as a new labour contracting model, in which workers are attached to firms by easily breakable, short-term fluid contracts rather than longer-term fixed ones

The attention economy is run on a gig economy labour model, in the sense that the workers - content creators - aren’t given fixed or secure contracts by the major sellers (or monetizers) of the final product, which are the platforms like Meta, X, Google, and smaller players like Substack. Let’s look a little deeper into the key dynamics of the gig economy.

Gig Economy 101

To understand the gig economy, imagine your head being detached from your body.

Traditional corporations integrated heady stuff - the senior and middle management who did strategy and coordination - with bodily stuff, the lower-level workers who did most of the ground-level production. All were held together as a complete organism through fixed contracts (see my Lego Model of Corporate Capitalism).

Gig economy corporations, by contrast, sever the management layer from the worker layer, creating a disembodied Head that relies on a churning pool of workers - the Body - to connect into their platform to do the ground-level production. Without that ‘body’, the head is but a hollow IT infrastructure.

The Faustian bargain of the gig economy model is that workers technically get more flexibility, but lose perks and protections. Let’s go to the transport sector, for example. The self-employed Uber driver is called an ‘entrepreneur’ or ‘contractor’ by Uber. The driver supposedly ‘runs their own business’ and ‘works for themselves’.

From an economic power perspective, though, the line between an Uber driver and an employee of a taxi firm is very very thin. They’re basically the same person under a slightly different labour contracting regime, with the added element that they’re now responsible for financing smaller assets that firms previously would have financed themselves, like individual cars. If you zoom out and look at it from a birds-eye-view, Uber is a giant taxi firm that gets its workers to bring their own capital assets to work (imagine a white-collar firm asking its employees to haul in their own computers and stationery into the office each day).

If you’re zoomed into the micro ground level view - the fact that the driver is technically self-employed - you can easily miss this macro level picture. At a macro level, the main distinction in our economy is between those who own large concentrations of assets and those who don’t. Both an Uber driver and an employed taxi driver of a taxi firm are in that latter category. In relative terms, they’re not major owners of capital in our society, while the platforms like Uber are.

Similarly, a Dickensian cloth factory owner in the 19th century was a relatively large owner of capital, while his individual workers were not. In power terms, then, a 19th century factory lord and an Uber exec are in a similar position, and their respective ground-level workers are in a similar position too, but the nature of each firm’s assets are slightly different.

The factory lord works with the original business model of capitalism, which was to accumulate concentrations of tools, machines and materials - the proverbial factory - and to get workers to operate them for him. This is what old Marxists would call ‘owning the Means of Production’.

The Gig Economy platforms, by contrast, run a lean version of this. A company like Uber knows that it doesn’t actually need to own tens of thousands of cars - the Means of Production - provided that it owns an information and management architecture that stands between those productive assets and society: Uber owns the Means of Connecting, rather than the Means of Production, which means they can still be a gatekeeper between workers and consumers, while outsourcing finance costs to the individual workers.

The fact that Uber drivers finance and provide their own low-level capital assets - cars - is one reason why they end up getting called ‘entrepreneurs’ (or ‘micro-entrepreneurs’), but again - in power terms - they really aren’t in such a different position to a factory worker. After all, a Dickensian factory lord could also choose to label each of his workers as a ‘micro-entrepreneur’, independently selling a ‘service’ - their labour - to operate his factory. Is that really so different to the driver, who gets up every day to sell their labour to Uber?

Uber will claim that it’s a mere middle-man, and that the drivers are in fact selling their labour to you, the customer, but the old factory owner could claim exactly the same thing: isn’t he just a ‘middle-man’ between workers who sew the cloth and the consumers who will buy the stuff? In both cases, the owners of the firms make zero revenue unless workers turn up: you will not find the factory owner threading needles to stitch corsets for Victorian England, any more than you’d find Uber execs ferrying drunk people around a city. There’s no coal without low-level workers getting dirty at the coal face.

Concessions on the coal face of content production

YouTube, much like Uber or a 19th century factory owner, makes no revenue without workers. They sell no advertising to their advertiser customers unless YouTubers turn up to produce the content that will attract the eyeballs. A platform like Substack has a different business model to YouTube, but is the same position vis-a-vis content-creators: they rely upon us writers to produce the articles that’ll give rise to subscription revenue. All attention economy platforms, from X to TikTok, are powered by their content-creators, but right now the managers of these platforms get holidays and sick leave, while the workers at the coalface don’t.

Remember that concessions and perks like sick leave, maternity leave, holidays and the two-day weekend didn’t used to exist. Workers had to fight for them. Some of these concessions were made by the proverbial Dickensian factory owners to prevent socialist uprisings and revolutions. At other times they realised they got more out of their workers if they gave them time to rest. In the case of the weekend, they also realised that it gave workers more time to consume, which was required for the overall system to clear and sell all the goods that workers produced during the week.

If you look at the rise of the gig economy model through cynical eyes, it does look a lot like a backdoor way to dissolve those protections. It is, however, a sophisticated way to do so, because gig economy corporations swap one set of concessions for another: you lose the holidays, sick leave and protection, but do get marginal flexibility. This is why gig economy platforms thrive in areas where workers are relatively interchangeable - the platforms are indifferent to workers leaving, provided that new ones are connecting in to replace them (and connecting in at a faster rate than they’re leaving). They want workers to fire and hire themselves, rather than managers having to do it.

So, each time a worker takes a break from a gig economy platform, they’re basically firing themselves. In the realm of the attention economy, though, this model eventually starts to harm the actual quality of work. Without any official holiday periods, the content creators must often push themselves to work all year without breaks, and this is heavily exacerbated by the algorithmic curation models of these platforms.

Long gone are the days in which platforms merely offered a centralised place to distribute content in chronological order. Now they curate it, selectively filtering it, and pushing it to selective people via algorithmic feeds.

As an attention economy producer, then, you have a real-time reward and punishment system: the more you clock in to work, the more you might be promoted, but - unlike a promotion in a traditional company - that promotion is temporary rather than permanent. You can spend years building up a higher profile by producing endless content in a particular niche, but the platforms are often designed to demote you as soon as you attempt to take a break.

You can literally see this in the eyes of burned out YouTubers, as they apologise to their audience about why they haven’t been producing content at a regular enough pace. What they’re trying to say is ‘I’m fucking exhausted, but if I stop producing at the same rate, the YouTube algorithm will start pushing my content down the rankings’.

This problem is well known, and I - as a Substack writer and ‘content creator’ on other historic platforms like Twitter - know it very well. I had a very serious breakdown-burnout in 2022, in which I couldn’t write for over six months. At that time I had a book coming out, so I had an alternative means of income for a bit, but it was pretty damn terrifying to sense the platforms retreating from me as soon as tried to temporarily retreat from them.

Even people who are doing well on these platforms face serious insecurity if they had to clock off for a couple months. Imagine, for example, if they’re suffering bereavement, or depression, or a divorce, or have to help out a parent who is ill. There’s no ‘compassionate leave’ option on these platforms, and there’s a generalised sense that if you take a break, others might be immediately promoted in your place.

Something isn’t right about that. It’s wack that mid-level Instagrammers trying to take a holiday will have to take their camera along with them to produce monetized content about the holiday they’re trying to take. It’s also wack that some of that revenue being generated by them on their half-holidays will be passed on to fund the fully-paid full-holidays of Meta bosses.

An imperfect solution

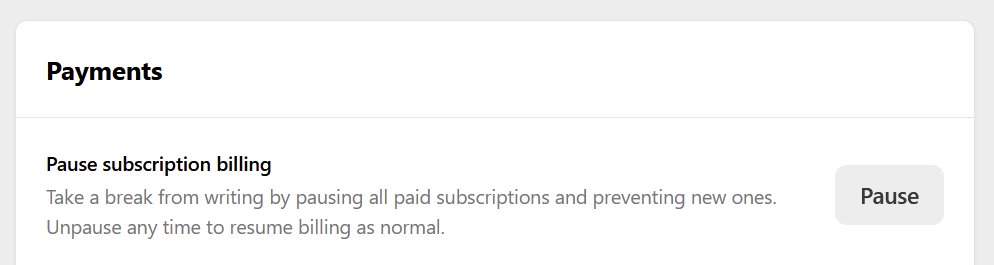

Substack allows writers like me to push pause on subscription payments, and the wording they use for it reveals the point I’m making. Sitting alongside the Pause button is the line, “take a break from writing by pausing all paid subscriptions and preventing new ones”.

I understand why they have this - if subscribers keep paying me while I don’t produce, they start getting annoyed, so it’s the business equivalent of an unpaid holiday.

There’s some complex psychology to this: as your finger hovers over the Pause button, you’re imagining the income being turned off, but you’re also imagining the possibility of your visibility being turned off, and your ranking being reduced - if you’re temporarily not open to paid subscriptions, perhaps the system isn’t going to showcase your work. Maybe whatever secret algorithm is being used will demote you and you’ll have to fight your way back up when you return. Who knows?

Substack has released a little bit about how their curation algos work, and their main claim is that they have a better model than advertising-driven platforms (who try to get users to drift endlessly through feeds to maximise exposure to advertising). I support the Substack mission, but while they talk about how their curation broadly works in matching writers with readers, there’s nothing on what happens if writers take a break.

In the gig economy world, it’s typical for platforms to maintain that they’re mere middle-men for self-employed people, but the reality is that they simultaneously present themselves as being more than mere middle-men. Much like traditional corporations will try to boast about how good they are to their employees, gig economy platforms will try to attract workers by offering better services and to present themselves as compassionate partners serving our needs.

Well, writers and content-creators need holidays, and I truly believe that Substack, YouTube, Instagram and all the others could get a lot of goodwill if they start pioneering new gig economy protections. I know they’re not going to offer paid holidays to us, but the least they can do is guarantee that we won’t be punished for taking leave.

So here’s my request to Substack, and all the other attention economy platforms. Your mid-level programmers get to relax on holiday, knowing that they can return to their same position when they get back. In that spirit, get these engineers to design for us content-creators a big button that says ‘Take Holiday’. Program it so that when we push it, our current algorithmic ranking is fixed in place and protected while we take a rest. Creators who have put in thousands of hours to rise up the ranks shouldn’t return to find themselves at the bottom of the ladder again.

I’m pushing pause

I hate to say it, but current gig economy platforms aren’t actually that different to our aforementioned 19th century factory owner, who offered no guarantee of repeat work to labourers who lined up each morning trying to win a daily wage. Those workers also felt they couldn’t take holidays, and those workers also worked on the weekends, because - well - weekends hadn’t been invented yet.

Like thousands of other content creators, I finished this piece on the weekend, justifying to everyone why I’m going to take a couple weeks off by producing content about the difficulties that come with being a content-creator.

I haven’t taken a holiday for a year, so with that, I’ll be pushing pause on payments for my dear paying subscribers, and I’ll be hoping that I don’t get demoted down the rankings by Substack’s managers and their algorithm while I do that. I do know though, that both of those parties - readers and managers - benefit from good content, and I do know that content benefits from good breaks.

I’ve just pushed pause on paid subscriptions for a couple weeks, which also prevents new sign-ups, so if you want to upgrade to a paid subscription to support ASOMOCO, leave me your details on this form, and I’ll contact you when I re-open the paid option. Cheers!

I'm wondering why they prevent new people from subscribing to the work of creators who are taking a break?

As your note at the end there implies, there's no reason at all why someone mightn't discover your work while you're on holiday and immediately want to join the ranks of your paused subscribers (on the understanding that their payments will only actually begin when you return and start offering new content).

So why do Substack deliberately prevent this? Why actively turn off readers' ability to subscribe to creators who are taking a pause? Is it purely in order to make the idea of taking a holiday feel more uncomfortable and so discourage it..?

Unless I'm missing something, that seems another thing they could very easily remedy to improve matters, if they wanted to.

Anyway, enjoy your well-deserved rest, Brett!

Enjoy your holiday Brett!! Time away always brings about new perspectives for me. Hope it does the same for you!