The Green Room

What the Epstein Files tell us about elite loneliness

Paying subscribers can access the audio version here!

Dear readers. I debated whether I should add to the hot-takes around Epstein, and what I might meaningfully contribute to the already saturated discussions. I decided to explore a topic that has long been of interest to me - what the files might tell us about elite loneliness and fragility. There are many aspects of the Epstein saga that I don’t write about below, so please don’t think of this as an attempt at anything comprehensive. It’s just one thread to consider among many.

At first glance, the network of power players featured in the Epstein files seem totally detached from our everyday reality. These people appear to occupy a realm above the law and beyond the state, living in a parallel universe with its own morality. They pull strings and make deals like demi-gods trading favours.

And yet, I feel this ‘supervillain’ interpretation of elites is unsatisfactory, and I’ve always harboured an intuition that it’s better to highlight elite weakness rather than strength. People who end up in positions of power are often not there because they’re particular profound, or strong, or even nefarious, but rather because they’re trauma-ridden vessels who offer the least resistance to the inhuman forces of our economic system, and who are therefore, almost evolutionarily, ‘selected’ by it.

Put differently, it might be the case that stronger people actually do worse in our system, because they’re less likely to bend themselves to its demands.

I know that perspective is a bit simplistic, but the alternative interpretation - in which the rich and powerful are seen as either angelic superheroes or demonic supervillains - is equally simplistic. The reality is probably somewhere in-between: many of the world’s high-flyers throw themselves into obsessive power-mongering to compensate for frailties elsewhere in their lives.

It’s in this context that Epstein slowly entrapped many elites into structures of complicity, and at the dark centre of that was an abhorrent core of sexual abuse and trafficking. In folk mythology, this leads to those sensationalistic Satanic paedophile stories in which we imagine a dark cult of vampiric overlords.

This certainly is one angle on the story, but I’m personally more interested in the much more mundane ‘banality of evil’ layers that lie around that dark centre - the thousands of daily practices that seemed innocent, like the insecure-but-vain university professor who feels flattered by getting an email from Epstein, and who quickly shoots back a response, or the business mogul who desperately wants to seem more bad-ass than he actually is, and who really thinks that hanging out at shit parties on islands makes him a cool kid.

I’m interested in the insecurities of elites, and how they’re all subject to very normal human vulnerabilities, like the desire for inclusion, status and connection.

It’s very obvious that many powerful individuals wanted to be in Epstein’s orbit out of FOMO, because they felt like it was the place to be, and that they might be missing out on something if they weren’t. To use the words of Paul Caruana Galizia and Kaye Wiggins, a figure like Epstein operates a social Ponzi scheme, where his earlier waves of connections become attractors to bring in more.

All sorts of jet-setters - from lawyers to academics, CEOs and journalists - were clearly attracted to Epstein’s connectivity, and wanted to be in his good books. And he - like the arch-villain Moriarty in Sherlock Holmes - wanted to be in the centre of such a spider’s web, catalysing meetings, job opportunities, political favours and deals via email and soirees.

I think what we struggle to wrap our heads around is the simultaneity of power and fragility in these interactions. For example, there is something deeply messed up about the former UK business secretary Peter Mandelson casually emailing Epstein saying it would be useful for JPMorgan to ‘lightly threaten’ the British chancellor in order to water down legislation designed to tax banker’s bonuses. And yet, the chumminess of their interactions also smacks of that vibe you get in groups of teenage boys, where they’re anxious to please and impress each other. There’s even something strangely endearing about the fact that the masters of the universe want to joke with each other, or send each other memes, or have selfies together.

When looking at that table full of photos collected by Epstein (see above), you sense that while this super-connected power-broker was a master manipulator in a web of influence, he was also simultaneously like that kid who tries to get his status by being seen around the in-crowd, and placing himself in the middle of it.

In fact, it reminds me a lot of sections of Donald Trump’s 1987 bestseller The Art of the Deal (yes, I have read it), where Trump sits in the high reaches of his Trump Tower, name-dropping all the important people that he likes to phone up from there, talking about what a big man he is and all the important stuff he’s going to do with all his important friends. It seems simultaneously impressive and pathetic. You sense that behind his loud boasting about bigness, there’s a lonely little boy sitting by himself wanting to be loved, concealing his underlying insecurity about smallness.

I’m not necessarily judging that - hey, we all want to be liked - but while some people seek status by being brilliant at some niche skill, others, like Trump and Epstein, seem to seek it by being super-connected. The tendency of such a person is to obsessively showcase their personal relationships with other powerful people, so that their conversations can turn into long bouts of humble-bragging, full of anecdotes about so-and-so CEO or financier or newspaper owner or film star or quarterback.

Now here’s a little twist. It seems that in order to position himself as an elite-level practitioner of super-connectivity, Epstein took advantage of the fact that - for most elites - being on top of the world is literally lonely. His social grift was based on offering them some kind of relief from that, by giving them the chance to enter a transnational green room.

Green-Rooming

Anyone who has ever been involved in performance of some kind - whether you’re a keynote speaker, a politician or a member of a band - will know about the green room. This is the specially designated backstage space where a performer can relax before or after a show. It’s designed to be free from the pressures of fame, a little enclave in which it’s a faux pas for attendants to ask for an autograph or selfie.

There are many ‘green room’ spaces in the world. They include private members clubs and elite nightclubs, where the bouncers are tasked with getting rid of fans who wish to worship the idols, so that the celebrities can pretend to be normal human beings for the night.

There’s a reason why celebrities are attracted to such spaces, and why they become cagey when normies are let in. It’s because they feel that the public only see them as abstract symbols or sources of reflected status to be consumed. In a Beatles interview, George Harrison noted that the main problem with fame is that people you meet:

… forget how to act normally. They are not in awe of you, but in awe of the thing that they think you've become

Many elites find this phenomenon, in which they are treated as objects rather than subjects, to be a dehumanizing experience. In fact, if they allow themselves to only be surrounded by sycophantic hangers-on, they can start to lose a grip on reality. Being swamped by fawning or extractive yes-men can amplify delusions of grandeur, but can also make them feel deeply isolated and unstable.

In this context, when someone like Epstein pops into your DMs and treats you as an equal, or offers a sympathetic ear, or promises confidentiality and straight-talking advice, it’s appealing. In many ways Epstein was running a vast green room operation for anyone who was performing on the transnational stage of the global economic system. This might include partners at Goldman Sachs, but it could also include prominent left-wing radicals like Noam Chomsky and far-right strategists like Steve Bannon.

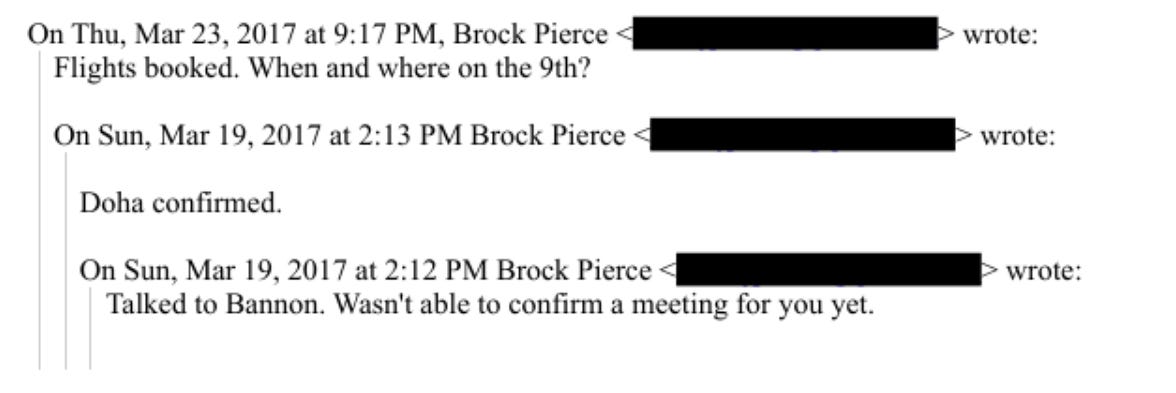

In fact, the three-way relationship between Epstein, Chomsky and Bannon is probably one of the most fascinating things to come out of the files so far. Epstein not only formed close relationships with both men, but introduced them and got them to interact and, almost, to collaborate. In 2019 Bannon started working on a documentary with Epstein to help rehabilitate the financier’s image, suggesting that Chomsky get involved too. Epstein messaged Bannon, saying “cant get further left than him or right than you. . its like hitler and ghandi. Sharing a hotdog.”

Chomsky and Bannon do appear to be polar political opposites, but they are united in the fact that they both specialise in shaping public opinion. Influencing the public is a specialist elite role, and the people who do it - on both the left and right of the political spectrum - have a common outlook in which they view the public as a kind of prize to be won over. Indeed, many elite intellectuals see themselves as being in a big public boxing ring, and, like boxers, they might diss each other in public while having grudging admiration for each other in private.

People like this are intellectual warlords, fighting for followers, and two warlords can feel an affinity for each other that’s not based on political orientation, but rather on shared circumstances. They are part of the same class, and after they leave the fiery television debate with each other they’re going to end up hanging out in that green room, off camera, away from the public eye.

At a simple human level, celebrities like this are prepared to share space with each other not so much out of vanity, but simply because they tend to feel more understood around other celebrities, less put on display, and more treated like peers. This can help us to understand the weird combos of people hanging out in the Epstein circles, and why we find emails between Chomsky and Bannon, or pictures of Bannon chilling with Woody Allen.

Many doors to the Green Room

Epstein, though, was always but one high-level node in this elite network, and it’s not like he was the only access point into it. For example, I have a well-known left-wing friend who occasionally got to chat with Bannon in an upmarket workspace in New York, where a weird mix of psychedelics influencers, blockchain grifters, venture capitalists, Burning Man event organisers and edgelordy philosophers would rub shoulders.

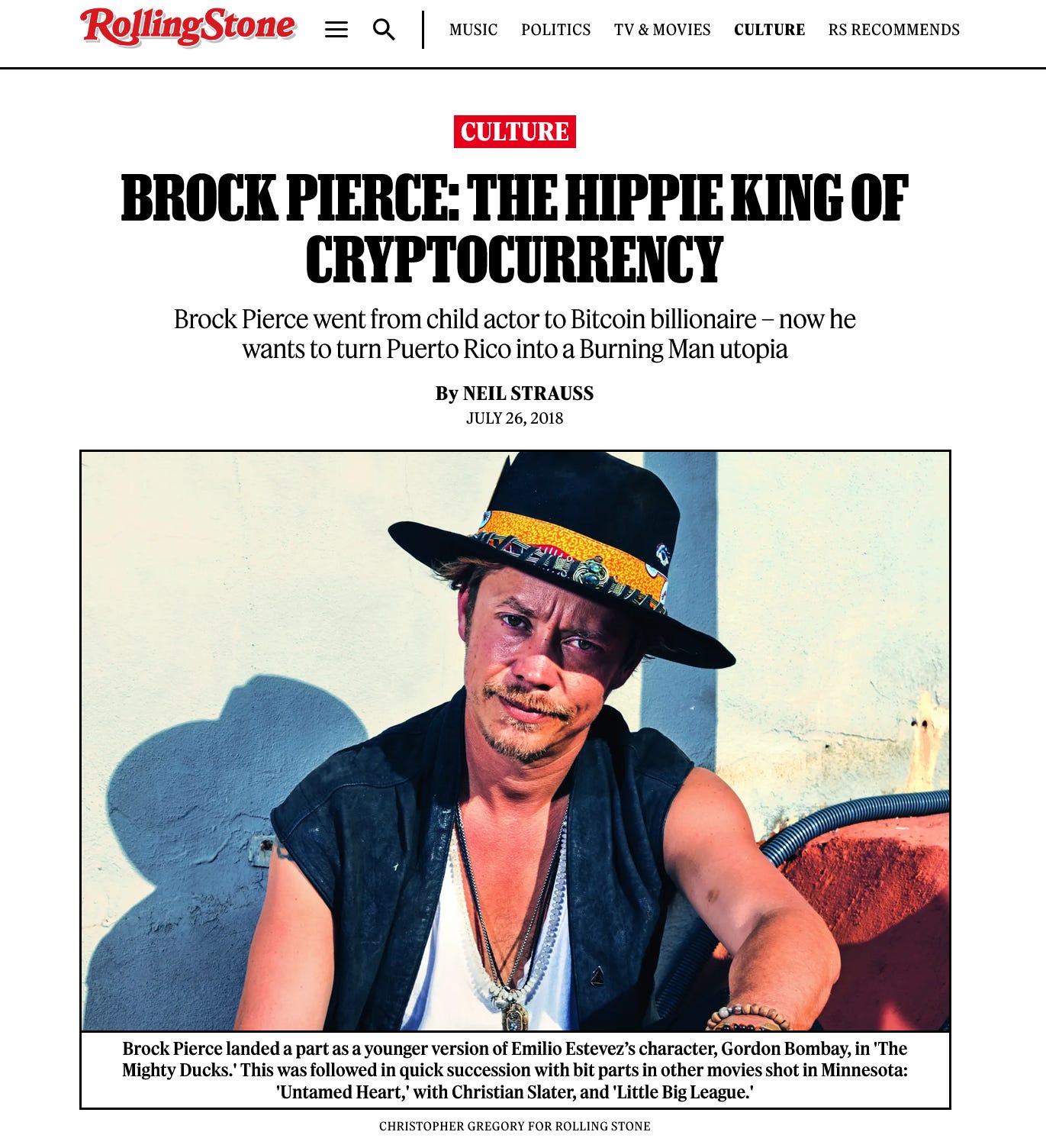

I remember being there when Brock Pierce - Bannon’s former employer, and co-founder of the stablecoin company Tether - decided to launch ‘Puertopia’, a crypto-currency ‘utopia’ in Puerto Rico. Brock was swanning around the salons of New York, running shamanic ceremonies, talking about sacred geometry, extolling free markets, and talking about the tax advantages for the super-rich to relocate to the island. There was a frenzy among all manner of minor elites to be in on this batshit scheme, and before long they were booking their obligatory plane flights and posting their vapid Instagram pictures from the island, talking about the new society they were going to build.

There are 180 pages worth of search results for ‘Brock Pierce’ in the Epstein files. A lot of that is just LinkedIn updates, but there’s also extensive evidence of the two men having meetings and calls, some of which bring in Bannon…

The point, however, is that Brock himself is an elite purveyor of green room connectivity. Hell, Brock even invited me to connect on Facebook (we’re still ‘friends’) so yes, even I am in this globe-spanning network.

The reality is that the global ‘green room’ has many entry points and many layers, like a members club with gold, platinum, silver and bronze tiers, offering status to everyone from mid-level influencers to startup founders, journalists, academics and basically anyone who is in the business of trying to alter the course of society in some way. This becomes the grounds for sociality, gluing together many unlikely actors.

For example, the British left-wing journalist Laurie Penny encountered Brock when she infiltrated a luxury blockchain cruise to do an exposé of it. Brock was a guest of honour on the cruise, and they end up partying together, forming that shared sense of camaraderie that comes from getting fucked up with other people. Despite occupying very different points on the ideological spectrum, they end up fond of each other, and she gets an invite to an after-party at his house:

I promise not to write about what happens at this party, because I’m off the clock, and I keep my promises, even though it was the only part of the whole adventure that gave me any hope whatsoever for the future of humanity… I may have got hammered and chalked some socialist poetry on the walls. I may have listened to straight-laced, lost-looking businessmen tell me about their secret sexual predilections as hippies played the same songs hippies always play on the guitar at four in the morning. I may have fallen asleep in a puppy-pile of half-dressed futurists. I promised no more details.

Another journalist who captures this very same sense of strangely vulnerable elite insider-ness is Jemima Kelly of the Financial Times, when - in August 2025 - she hung out with the far-right edgelord king, Curtis Yarvin, at an elite invite-only party in London.

Yarvin has long been a figure on the so-called ‘intellectual dark web’, and is a key node in the ‘neo-reactionary’, anti-democratic Dark Enlightenment movement, which includes figures like Peter Thiel, Nick Land and JD Vance. Jemima’s story starts with a scene that encapsulates the global green room, with supposed enemies - the ‘liberal elite’ journalist, and the ‘anti-woke’ agitators - hanging out in the taxi together.

She goes on to detail the various characters at the party they go to, and - like Laurie Penny with Brock Pierce - it ends with that shared sense of comfy solidarity between unlikely protagonists. Jemima notes that:

When we finally say goodbye, Yarvin gives me a warm hug. Shortly after, he texts asking me not to mention a salacious story he told about a celebrity. (Yarvin talks so much that I don’t really recall which story he means.) “My philosophy,” he writes, “is that the relationship of a source to a journalist should be long term and not a quick, cheap bang.” A few moments later, he follows with: “I don’t want to have to use a condom. Metaphorically speaking.”

To many on the political left, Yarvin is seen as a kind of bogeyman, a high lord of neo-fascism, but in social life he’s a ‘liberal elite’ like any other, taking the taxi, turning up at the cocktail parties, and sending cheeky messages to his journalist friends and anyone else who feels like community. He, like Jemima, is in that position of shaping public opinion, and he undoubtedly prefers to hang out with her in the green room than to sit down for a meal with the distant people whose opinion he shapes (ya know, the Christian moralists or white supremacists).

The Frailty of Power

There is something elusive that I’m trying to put my finger on. Maybe it’s this simultaneously gross-yet-endearing way that supposedly powerful, god-like figures really often just want to be liked by their peers. We see it in people like Trump, and we see it in photos of the crown prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia with his arm around Epstein, as if they were university mates on a night out.

Perhaps this is the surreal through-line that connects someone like Noam Chomsky via Steve Bannon to Elon Musk. There is much correspondence between Epstein and Musk, but the latter insists that he never tried to get onto Epstein’s island. It’s clear though, that Musk is riddled with the very same desire for acceptance into in-crowds, so let’s conclude with a curious case from 2022, when Elon turned up at the door of the legendary alternative nightclub Berghain in Berlin, bastion of the counter-culture, but didn’t get in.

Elon claims that he refused to enter, due to a peace sign being painted on the wall, but the true story for Berliners is that he got bounced by Sven Marquardt, the infamous doorman of the club, a person over whom Elon has no power.

I can picture Elon’s feelings of humiliation at being turned away, partly because I too am a white South African, and I can imagine all his childhood memories from his boyhood in Pretoria, when all the mean, thuggish 1970s rugby jocks of apartheid picked on him. We grew up in a fascist country, surrounded by Christian nationalists, and such people are not friendly to nerdy types.

Yes, there is of course some ‘homecoming’ story to Elon’s own turn towards fascism in the last several years, but whenever I see him I see that strange interplay between power and frailty. The supposedly almighty Musk feels humiliation like anyone else, and has to get up the morning and take a piss like billions of others for the last 200,000 years, and will eventually disintegrate into the ground like they did. Through the eyes of the vast universe, Elon is tiny and fragile. In the grand sweep of millions of years, there is literally no difference between him and a rural peasant farmer of the 15th century. They are equally ranked.

As they say, a monkey in silk is a monkey no less, and - likewise - a person with an 11-figure bank account still experiences exactly the same vulnerabilities as all others. The main difference, however, is that they can use such a bank balance to express those vulnerabilities in the form of ridiculous displays of ostentatious spending, or delusions of immortality, or fantasies of space travel, or private parties where the boundaries between utopian fantasy and nightmare can be very thin.

Interesting but I think it misses the context. Your "frailty of power" and "green room" frameworks risk an overly charitable, apolitical reading by focusing on universal human insecurity.

Personally, giving this take is very close to giving sympathy to people who chose to be wealth addicts and status whores while doing heinous things. I have nothing but contempt for this class when they could do so much good with their wealth and power but mainly use it for self indulgence & screwing the masses over apart from the acts directly linked to Epstein. They can cry me a river.

A sharper lens is that of pathology, operational intelligence, and, critically, enforced conformity. The behavior you describe is less about shared vulnerability and more about the specific, amplified pathology of the power-wealth-status addicted, operating within a system of rigid social conformity. This isn't just individual frailty; it's the status anxiety, empathy erosion, and narcissistic supply-seeking endemic to an ultra-wealthy ecosystem, where deviation from the in-group's norms carries the ultimate social cost: exclusion or worse.

This conformity has two powerful aspects: "play along to get along" and groupthink. The first is the strategic, & personal—the conscious decision to suppress discomfort for fear of social or professional ostracism. Norman Finklestein basically told him to F#off. The second is the emergent, collective pathology that takes hold when everyone is playing along. In the insulated green room, the lack of dissenting voices creates a potent groupthink where Epstein's increasingly aberrant world could be rationalized as eccentricity, "how the game is played," or simply none of one's business. This wasn't passive conformity; it was an active, collusive silence born of status anxiety and enforced by group dynamics.

The "green room" wasn't just a sanctuary; it was a conformity-enforcing mechanism. The desire to belong, to be "in the know," and to receive validation from the only peers who matter created immense pressure to overlook red flags, accept abnormal behavior as "eccentricity," and participate in collective debauchery. This conformity bias is what allowed the "banality of evil" to flourish—it wasn't just mundane, it was mandatory for continued membership.

Crucially, this psychological and social landscape—fueled by conformity—was the perfect operating environment for something far more calculated. To separate the "banality of evil" from Epstein's "dark centre" misses the point: the banality was the tactical surface. The flattery, the networking, this was the essential camouflage and mechanism for what evidence suggests was a sophisticated intelligence honey trap operation. Investigative work, by Whitney Webb-now validated-and others places Epstein within a long history of state directed intelligence & blackmail, where kompromat is the product and influence is the goal.

Therefore, the elites' "frailty" and their compulsive conformity weren't just tragic flaws; they were the twin self-inflected vulnerabilities exploited in a strategic game. Their desperate need for in-group validation within your transnational green room blinded them to the fact that the room was a controlled enclosure, wired for sound and blackmail. The real story here is how extreme wealth cultivates a pathological in-group conformity & strategic immorality, which intelligence operations are expertly designed to infiltrate and weaponize. The true "frailty of power" is that the very mechanisms elites use to secure their status (conformity, exclusive networks) are the precise factors through which they become controlled. It's like talking about human frailty in the context of ADF soldiers having PSD no thanks.

This is a fascinating read, and rings with a lot of truth... but it also makes it a little too easy to overlook the fact that the 'batshit fragiles' also get sucked out by a riptide into deep unchartered waters, where their bizarre power + narcisissm also brings along with it all kinds of potential bloodbaths, incl. rape, murder, mafioso behaviors, and geopolitical wars w/ gruesome-scale massacres and/or genocides...