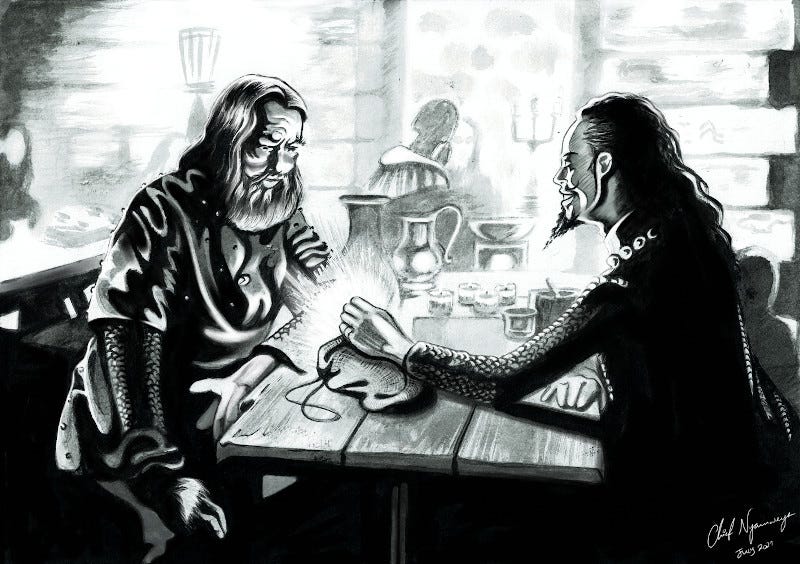

Picture this scene. You are a weary 12th century traveller quietly sipping an ale at a tavern. A man approaches you. “I have something that’s in very limited supply,” he whispers to you conspiratorially, before asking, “would you like it?” You look at him suspiciously, and, over the drone of bard music, reply with, “depends on what it is”.

He sits down and continues. “It’s something that can be split into pieces and moved around”. You shrug and say, “I’m already carrying a lot of stuff, so tell me what it is first”. “It’s almost weightless,” he adds with a wink, “and cannot be seized from you”. Now you feel irritated. “Listen, can you actually tell me what this split-able, moveable, lightweight, unseizeable thing is?”

He seems offended. “Surely those are features enough my friend?” You growl back with “look, syphilis is lightweight, movable and cannot be taken away either, but that doesn’t mean I want it.” “Come on!” he shouts out, “I’m offering you something scarce that can be passed to others across borders!” You slam your drink down: “Tell me what the thing is and then I’ll tell whether I care. Are you trying to hand me gems, bubonic plague, seeds?”

He backs off, saying, “It’s an object”. You retort with, “I don’t want a random object”. “What if it were beautiful?” he asks. You give him one final chance, replying with, “Is this object you have beautiful?” His final response is, “Ah, no... but it has a beautiful emblem. Let’s just say it is… um… a token. Many have been buying it. I’ll sell it to you for two ducats”.

The moral of the story

There is a simple reason why the man in the story above is so frustrating. He insists on describing features around the object he is promoting, rather than describing the inner essence of the object itself. This same practice is extremely common within the Bitcoin community. This essay will explain why, and in doing so will reveal a hole hidden in the heart of Bitcoin.

I will lay this out in five parts, as follows:

Part 1 will explore the use of nouns versus adjectives in our descriptions of things, and how they are used to convey primary and secondary features of things.

Part 2 will explore how to describe the noun ‘money’, but without resorting to vague and evasive ‘functions of money’.

Part 3 will explore the surface level numbers that accompany a monetary system, and question to what extent they are nouns or adjectives, before applying this analysis to Bitcoin. This will reveal that the numbers that accompany normal money are numerical adjectives, whilst those that accompany Bitcoin are numerical nouns.

Part 4 will show how the numerical adjectives of normal money are fusing to the limited-edition numerical nouns of Bitcoin, and how this creates havoc in the psychology of the tokens.

Part 5 will offer suggestions for how to fill in the hole in the heart of Bitcoin.

Part 1: An evasive noun beneath an adjective armour

Bitcoins are digital objects, issued out and moved within an elegant technological system. They are borderless, cannot (in theory) be seized, and are ‘scarce’ in the sense that there are a known number of them released predictably, rather than a fluctuating number released unpredictably. They also have a logo and a brand name. These objects get called ‘tokens’, but manifest as numbers on a screen, which is the only sensory information about them that a person can experience (they cannot be touched, tasted, smelled, or heard).

I have been involved in the scene around these tokens since 2011, and promoted them in the early years. I used to receive them in exchange for my first book, and would try to exchange them for actual goods and services when possible. In the early Bitcoin community the tokens were somewhat mysterious, but we initially ignored this because we were fascinated by the innovative way of issuing them and moving them around. But, like a baby moves from fixation upon the mere appearance of an object to eventually questioning what it is, the question for me became what are these tokens being issued and moved? What is a digital ‘token’ supposed to be anyway?

From early on, however, I noticed that many Bitcoin enthusiasts would avoid deeply addressing this question, or would simply bypass it by calling the tokens ‘coins’, as if that were description enough. I remember speaking at a big Bitcoin event where countless talks described how to move the tokens around securely, or speed them up, or protect them, whilst my talk was the only one asking what they were. Some of the audience looked irritated at this, as if it were obvious what they were, and as if such introspection was distracting from the serious business of building the technical systems around the tokens. This ‘introspection’, however, was directed towards by far the most serious question, and one that continues to be avoided. Let me illustrate.

1.1. The blind man and the token

Imagine a one-of-a-kind chair, hand-carved into the shape of an elephant. A blind companion that I am leading around asks me to describe it, so I say, “the thing before you is one-of-a-kind, movable and costs $800”. Did I capture the essence of this object with that description? No. I merely described ancillary features and adjectives that surround it. Adjectives are words that imply a noun, so when I use them without a specific noun being present they feel evasive, as if something is being avoided.

Now imagine the same person asking me to describe bitcoins. I say “they are scarce, borderless, censorship-resistant, movable tokens”. Did this truly capture their essence? In the mind of a blind person I conjured an image of some resilient limited-quantity thing moving around. All the adjectives point to this object, but what if the person tries to zoom in on this ‘token’ in their mind? Imagine them trying to visualise it, but finding it surrounded by an armour of adjectives with names like Scarce, Borderless, Unseizable, and Movable, and wanting to push beyond those. Imagine them trying to make contact with the tokens by saying “I know that you tokens are limited in quantity, and that you can move, but who are you?” My companion is seeking out the essence of the noun ‘token’.

1.2. Zooming in on essences

Generally speaking, adjectives and nouns form two classes of description. A noun is a primary symbol invoking imagery of the deep core of something, whereas adjectives are modifiers that add to or alter that. In the popular parlour game 20 Questions, people often work backwards from the latter to converge upon the former. Imagine an answerer being probed with queries like “is the thing you are imagining movable?” Upon receiving the answer “yes”, the questioners are a little closer to glimpsing the essence of the thing being imagined, but not that much closer, because movability is common to many things. Perhaps the answerer has a Projector in mind, but the core feature of a projector is held in its noun: being an actual projector is its essence, and no amount of referring to it as “a movable thing made in China that costs $350” is going to capture that.

It may be philosophically slippery, but we find it rather easy to feel out and describe these primary and secondary characteristics of most everyday things (albeit different objects inspire different levels of fixation upon either). For example, rum is movable and divisible, but – in general – I do not need to showcase that fact. If a bottle of rum is on a table, and will initially just describe it by pointing at it and saying “it is rum”. If the person I am saying that to has no primary experience of that noun, they will then ask me “what is rum?”, which will force me to ‘explode’ the noun out into a network of new words unpinned by new nouns, such as “an alcoholic spirit made from molasses”. The essence of rum can be sensed in the intersections of these new words, whereas pointing out its movability and divisibility would not capture that essence.

Secondary features – such as movability and divisibility – are not only characterised by the fact that they are too vague to allow me to hone in on something, but also by the fact that they do not generally tell me whether I should desire the thing. Consider, for example, this question:

“Do you want a scarce, long-lasting thing?”

This is a tricky question, because things like nuclear waste and a huge statue of Mao Tse Tung are scarce and long-lasting, and yet it is not obvious that those are desirable. The statement “do you want a beautiful long-lasting thing” can be more compelling, but what about “do you want a scarce beautiful thing that will perish almost immediately?” That is complex, because the duration and scarcity may modify how we perceive the thing, but can never in themselves say enough. Thus, sentences like “gold is scarce and long-lasting” do not convey any primary information to someone who is not already familiar with the primary essence of gold. Similarly, saying something like “Bitcoin is scarce, long-lasting, borderless, unseizable and movable” conveys no primary information to my blind companion, who has no pre-existing familiarity with the essence of the Bitcoin ‘token’.

Thus, before they can make sense of whether scarcity, movability and unseizability are desirable, my companion must first grasp the primary essence, which requires them to ask me “what is this token?” This in turn will require me to ‘explode’ the term ‘token’ into a network of new words with richer meaning. We will get to that, but let us first go through an example of how I would do that with a different type of token.

1.3: Tickets vs. printing material

Imagine I handed my blind companion a train ticket. It is a physical token, so they can feel its contours, but imagine them asking me to describe it more fully for them. In this case, I would explode the term ‘token’ out by saying “the token you hold is a legally enforceable promise, issued out by a company, that will guarantee access to a train”. I could also add in secondary information, such as “it is one of 500 printed on card, and you can transfer it by handing it to someone else”.

Imagine, however, if I flipped this ordering and began by describing those secondary features, saying “the token you hold is one of 500 transferable pieces of card”. If I stopped at that point, the definition would be useless, because a ticket is a legal promise printed on card, and it is the legal promise that is its primary essence, rather than the material it is recorded on (indeed, you could record a ticket on any material, or record it digitally). In the case of a physical train ticket then, the term ‘token’ refers to two sub-nouns – the body of the token might be card, but the essence of the token is legal promise. It is not mere card.

Consider now this sentence: “the Bitcoin token you hold is one of 21 million transferable digital tokens”. Such a statement is conceptually equivalent to saying “you are holding one of 500 pieces of card”, and conveys nothing to my blind companion. Just like holding a random piece of card is largely meaningless, holding a random digital token is meaningless too, unless we can give an account of its primary essence. But while it is easy to explode out the definition of a train ticket, how does one explode out that term ‘Bitcoin token’ into something more meaningful?

One option is to avoid such exploding, and to simply ‘kick the can down the road’ by upgrading the noun ‘token’ into a more evocative noun, such as ‘coin’, or ‘money’. My blind companion probably has some primary experience of what those terms are supposed to mean, but let us say – for the sake of argument – that they do not, and that they thus direct a new request to me, asking me “well what is money?” In Part 2 we will see how to explode that term out into a more evocative network of words.

Part 2: Describing the structure of money without resorting to functions

There is a rigorous way to describe money, and a lazy way. The rigorous way requires us to describe the structure of money, whilst the lazy way is built upon describing so-called ‘functions of money’.

This bifurcation between structural and functional definitions is not unique to money, and can be applied to any usable thing. Consider, for example, this description:

A solid horizontal square of wood of human bum-size, secured by screws to multiple vertical legs arranged perpendicular to it, accompanied by a vertical wooden back-rest.

This is a rough but relatively rigorous structural definition of a certain type of chair. Its accompanying functional definition might be “something to sit on”. By itself, however, that functional description is lazy, because you can sit on many things, such as the roof of a barn, the boot of a car, the edge of a volcano, your mother’s lap, or a yoga ball. Under the lazy definition then, all manner of structurally different things could be collapsed into the idea of a ‘chair’, simply by using that zone of functional overlap.

This causes the degradation of language, because while it is true that I can sit on a yoga ball, it is meaningfully different to a chair in structure, and there are things that either can do that the other cannot. For example, it is widely understood that you can stand on a chair to reach the top of a shelf, but try to do the same thing on a ball. Similarly, you cannot roll around on a chair to do ab exercises.

To describe a ball as a ‘chair’ you have to ignore the structure of each object and exploit the vagueness of a functional definition stripped of a structural accompaniment. Put differently, when a functional definition is separated from structural definition, it becomes floating and ‘disassociated’, and thus allows all manner of imposters to cloak themselves in it.

It turns out that using disassociated functional descriptions is the predominant way to describe ‘money’. When asked ‘what is money?’, many economists resort to a vague functional description which says money is a means-of-exchange, store-of-value and unit-of- account. This definition is literally useless unless it is accompanied by an actual account of a structure that is able to induce those so-called functions. This is why I refuse to use disassociated functional definitions of money by themselves, and why I always begin with structural definitions that can subsequently give an account for how certain ‘functions’ are enacted.

Monetary systems, like chairs, have an actual structure, but we struggle to see it because the structure so fully enmeshes us (much like a fish struggles to see water). We are small beings immersed in a totalizing system, and we tend to only notice its surface-level artefacts, like physical cash tokens, cards, or the numbers shown in our bank account. But a cash token is not mere paper, and the numbers we see in bank accounts are not mere numbers. They are accounting records of legally-enforceable promises held in play within a vast coercive network vortex that is almost impossible to think or act outside of, and which has core architectures that can be described like engineering schematics. Thus, if my blind companion was to ask me “what is money?”, I would begin like this:

A vast network structure, at the centre of which lies three sets of issuers issuing out three chained layers of legal IOUs – in physical and digital form – which will later return to the issuers to be destroyed, but which in the interim entrench themselves as economic network access tokens that circulate around an interdependent web of people who cannot mobilise each other’s labour without them. These tokens are activated in the context of legal systems set within political systems set within social systems set within ecological systems, and this mesh structure underpins modern capitalism and is etched into the very fabric of our being.

It is quite possible that, upon hearing this initial description, my companion will not fully grasp the nuances of what I have said. Indeed, most people would not, because it can take years of effort to glimpse the structure of monetary systems, but this does not mean the structure does not exist. I could go on to nuance this – showcasing the role of the state and the banking sector, and elaborating upon various internal battles, contradictions and instabilities within the structure – but that would take thousands of words, as I have to describe an entire complex system rather than a simple object like a chair.

The point of this essay, however, is not to describe the structure of modern money. For our purposes right now it suffices to say that there is a bifurcation between the ontological reality of the monetary system (what it actually is) versus the phenomenological experience of it (how a person encounters it and experiences it). The structure is simply too big to experience in full, which is one reason why people uncritically go along with those disassociated functional descriptions of money tokens. Thus, lurking in the back of many people’s minds is the idea that a monetary system is nothing but a mysterious set of numbered objects that mysteriously fulfil the task of ‘means of exchange’, ‘store of value’ and ‘unit of account’.

In reality, however, it is only the last of those ‘functions’ that is unique to money. The former two are so vague as to allow many non-monetary objects in (much like ‘a thing to sit on’ allows balls and guitar amplifiers to invade the definition of a chair). In refusing to cut directly to the core structure of money, the functional definition directs attention towards the surface-level artefacts of the monetary system – such as those numbers in an account, or cash tokens – but without describing how they work. This in turn leaves people susceptible to believing that those are ‘mere numbers’, or ‘mere paper’ held up by nothing but belief.

And, it is precisely this weakness in understanding normal money that allows Bitcoin’s adjective armour to not be pierced through, and which allows someone – upon seeing that Bitcoin tokens are movable numbered objects – to glibly say ‘Bitcoin tokens are money’ without being challenged. In Part 3 we will do some challenging.

Part 3: Numbers as adjectives versus numbers as nouns

In the realm of phenomenological experience, money appears with numbers. Put differently, we associate movable numbered objects with money. Numbers, however, have a very intriguing linguistic property, in that they can be either nouns or adjectives. In the pristine world of mathematics they are nouns, whereas in the practical world of accounting they are adjectives. Consider this sentence.

There were fifteen horses in the third edition of the Kansas Derby, and this time only four warnings were given to contenders in the eight races. One was fined $150.

Now consider this sentence, which contains all the same numbers.

Fifteen divided by three is less than four multiplied by eight, which is greater than one minus one-hundred-and-fifty.

In this second sentence the numbers are nouns. They are the main stars, rather than the supporting actors, and this only occurs in sentences pertaining to pure mathematics, where numbers appear as abstract essences-in-themselves. In mathematics, ‘4’ carries the essence of four-ness, and may be pitted against an ‘8’ that carries the essence of eight-ness.

By contrast, it is highly unusual to speak of numbers as agents or essences-in-themselves in ordinary language. We see this in our our first example sentence above, where all the numbers act as adjectives pointing to something beyond themselves – horses, editions, warnings, races, dollars. The essence of a phrase like ‘fifteen horses’ is a large quantity of horse-ness, rather than ‘fifteen-ness’. This is why nobody would ever claim that fifteen horses are ‘mere numbers’.

Nevertheless, due to the aforementioned problem of seeing the structure of money, there is a strong tendency amongst some people to say that 150 dollars are in fact ‘mere numbers’, as if the phrase ‘$150’ was a numerical noun with the dollar symbol affixed to it. This, though, is but a side-effect of partial vision. Monetary numbers, whether affixed to a cash token or written out in a bank account, are accounting records pointing to something beyond themselves. In the case of a bank account, the numbers point to a quantity of legal promises – IOUs – issued out by a bank, which grant access to legal promises issued out by the state. They are numerical adjectives, and the only way to render them as mere numbers (aka. numerical nouns) would be to destroy the banking and legal system, and the system of state IOUs that bank IOUs give you access to.

The act of writing out numbers in the normal monetary system is the act of granting access to a network vortex. For a simpler example of this phenomenon, consider our earlier example of the train ticket. The act of writing out numbers on a train ticket (such as ‘Admit 1’) is an act of granting access to an underlying train network. It is only if the trains, rail lines and train company was wiped out (perhaps in a freak apocalypse), that the ticket would be rendered into a mere piece of card with the numerical noun ‘1’ on it. It is only when the legal promise is wrenched away that the number ceases to be an adjective.

3.1. What are the numbers in Bitcoin?

Bitcoin, like the dollar system, comes with numbers. The top right of the image below, for example, shows 7.205 being attributed to someone’s address on the Bitcoin system. It certainly looks quite similar to something you might see in a bank account, but are these numbers adjectives or nouns?

For them to be adjectives, they would need to be accounting records pointing to something beyond themselves. From a technical perspective, however, a Bitcoin mining rig wrote out the number 7.205 and transmitted it to everyone else in the system after exerting a large amount of energy getting through Bitcoin’s ‘proof of work’ system. Was the mining rig accounting for something, or was it just writing out numbers after exerting energy? It is the latter. It just wrote out numbers.

These numbers do not point to anything beyond themselves, which means that in the Bitcoin world the numbers are numerical nouns. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the so-called ‘genesis block’ of Bitcoin. In the beginning, Satoshi Nakamoto’s computer wrote out the number ‘50’, which was the first numerical noun in the system.

The key nuance, however, is that the system participants later added a linguistic overlay to the numerical nouns by affixing the acronym ‘BTC’ to them, and describing those numbers as ‘Newly Generated Coins’. Turn your eyes to the left corner of the images above, where you will be able to see that phrase. The system places limits on how fast new numerical nouns can be written out, and how many can be written out, and also allows you to perform operations on them (splitting them and reassigning them and so on), but rather than speaking about the numbers directly, the community has developed an indirect proxy language in which the numbers are spoken of as ‘BTC’, ‘tokens’, ‘coins’, and ‘digital currency’.

3.2. Visualising limited edition numerical nouns

I have now got a little closer to being able to ‘explode’ the term ‘Bitcoin token’ out for my blind companion. I say “the tokens are numerical nouns – pure numbers – that have been printed within a network of computers after energy was expended, but which are controlled by a rule-set that places strict limits on how many numbers can be printed. These numbers are casually referred to as ‘coins’, and can be reassigned around the system.”

What exactly will go through my companion’s mind upon hearing this? Remember that they cannot see the system’s logo or branding, so will be free of any irrelevant secondary imagery that might otherwise serve as a distraction. They are trying to visualize ‘coins’ as numbers that took energy to write out, but does it really matter to them how much energy was required? Imagine finding the number ‘50’ etched out on a rock on the summit of Mount Everest. Someone had to crawl a long way before they could write that, but does it affect what the number is? Put differently, is a number written out with difficulty fundamentally different in essence to a number written out easily?

Even within the Bitcoin system the amount of energy required to write these numbers out has radically changed over time – the original ‘50’ written in the genesis block took almost no energy to write out, whereas that later ‘7.205’ took huge amounts of energy (there is no scope here to explain why, but let us take it for granted). To my blind companion, however, all tokens in the system – regardless of when they were created – appear the same.

3.3. Numbers as collectibles

It is possible that numbers found etched on the top of Mount Everest could be seen as novelty collectibles. Maybe someone could remove the piece of rock, take it to the bottom of the mountain and sell it to tourists, marketing them as limited edition numbers written out by adventurers in a faraway place!

Similarly, it is obvious that energy is required before a Bitcoin miner is allowed to write ‘7.205’ in the system – and thus the number can be presented as having a type of ‘digital scarcity’ – but that number cannot be held like a piece of rock can. My blind companion will have to imagine a set of ‘limited edition’ numbers, but – unlike a person with sight – does not have the ability to cover those over with logos and colourful imagery of metallic coins. The latter images are normally required to distract from the otherwise colourless reality of a pure number, and fill in the blank implied by the presence of all those adjectives.

This takes me back to the early days of Bitcoin. As mentioned, the early community was excited by the ability to write out limited-edition numbers and reassign them around the system whilst calling them ‘tokens’, but my original question – “what are these tokens?” – really can be rephrased as “what do these numbers point to?” The answer is simple. They do not point to anything. This can subsequently be interpreted in two ways: they are either pure numerical nouns (7.205), or they are numerical adjectives that point only to an absence (7.205 units of nothingness). This is the hole in the heart of Bitcoin. The only reason we fail to see this is that most of us have sight, and there is an entire industry that specialises in filling our view with images of coins, along with images of ‘mining’ and extraction. In Part 4 we will explore how this marketing apparatus works.

Part 4: Marketing ‘Mount Everest Money’

To present a numerical noun as money is not – in the first instance – very difficult, because of the prior weakness we have for seeing movable numbered objects as money. Just like a counterfeit note simply mimics the surface appearance of physical cash, so too can a number on a screen mimic the surface appearance of a bank account.

Nevertheless, to hide the hole in the heart of Bitcoin, the Bitcoin community cannot afford to fully associate its numbers with bank-account imagery – because it will be found wanting – so rather attempt to associate the numbers with metallic gold imagery. This returns us to our Mount Everest analogy above: the entire marketing apparatus relies upon the idea that the exertion of energy somehow makes the numbers into a ‘commodity’, which in turn enables the industry to pitch Bitcoin tokens as a ‘commodity alternative to fiat money’, despite the fact that numbers cannot be felt, smelled or tasted like gold might be.

Briefly imagine a scenario in which someone sets up a ledger on the top of Mount Everest, and allows those who have hiked up there to write one number into it. We could playfully refer to that number as ‘Mount Everest Money’, but – as mentioned – what is more likely to happen is for those numbers to be sold to tourists as limited edition collectibles. Tourists at a special base-camp market could buy them from people who have hiked up to the summit to harvest them, and this is exactly what has happened in the Bitcoin system: there is now a vigorous market for buying and selling arduously created limited-edition numerical nouns.

4.1. A numerical adjective for a numerical noun

This has created a very peculiar situation, because the numerical nouns have come to have a price, which is a numerical adjective denoting the quantity of dollars that a person must hand over to get a branded 1. This is the famed Bitcoin price that the media pays so much attention to.

It is at this point that the disassociated functions of money paradigm (described in Part 2) comes to Bitcoin’s aid. In a situation where someone is not trained to see the structure of the monetary system, and is rather encouraged to focus on vaguely defined functions, they can very easily begin to conflate priced numbered collectibles (pasted over with money-like branding) as being ‘money’. This is in contrast to, for example, a priced chocolate cake (pasted over with cake-like branding), which is seldom presented as money.

Actual monetary systems – as described in my structural definition in Part 2 – form the foundational setting within which markets unfold, and money tokens are not – in the primary instance – objects to be traded upon the markets they underpin. To test this, you need only walk into a supermarket with £20 in your hand. Upon looking at the money, your mind will project itself towards thinking about what you can buy with it, rather than what you can ‘sell’ it for (similarly, a supermarket owner does not experience themselves ‘buying’ your money with all those different goods on their shelves).

The reason for this is that everything in that local market is routing through the monetary system, and this is why the only functional definition of money that is worth paying attention to is the ‘unit of account’ concept, which recognises this distinction between money tokens and the goods they are used to price. This is a network concept, and while there may be multiple currency networks in the world, when you are within one of them you are subsumed by it. Thus, within the UK network there is a structural separation between, firstly, the British pound and, secondly, everything priced within the pound ecosystem. You cannot ‘price’ British pounds in Bentley cars or Tetley’s Tea any more than you can claim a tornado is being ‘sucked in’ by the pieces of debris flying around it.

One reason people get confused, however, is that there is one very specific ‘market for money’ that forms on the boundaries between these networks, where the vortexes meet. It is called the foreign exchange market, and it is actually a zone of swapping one form of money – which reigns supreme as the primary pricing vortex in one geographic area – for another, which reigns supreme somewhere else. We can easily see that a chocolate cake is not part of the FX market, but a numbered collectible pasted over with money-like branding – such as Bitcoin (or the ‘Mount Everest Money’) – can use its numerical appearance and adjective armour to try pass as a contender there, even though there is no supermarket in the world that uses it as its primary pricing vortex.

The ‘unit of account’ is the strongest of the functional descriptions of money, but Bitcoin tokens fare the worst on this, precisely because – in structure – they are far from being money. Nevertheless, Bitcoin promoters are able to combine the ‘money-like’ visual appearance of Bitcoin’s branding with the linguistic ambiguity of the other two ‘functions’ of money – the so-called ‘store of value’ and ‘medium of exchange’ functions – to partially brute-force the token into the idea of money (in a kind of ‘two out of three ain’t bad’ fashion).

4.2. Exploiting the ‘store of value’ concept

They can do this because the collectibles have a price, and ‘price’ is often conflated with the much broader concept of ‘value’. In reality, however, the phrase ‘Bitcoin is a store of value’ just means ‘Bitcoin collectibles can be bought for money and maybe resold for more money’. This is a feature common to many non-monetary items within a monetary pricing vortex, such as houses or Radiohead vinyls, which also take energy to produce.

Similarly, a phrase like ‘Bitcoin’s purchasing power is increasing’ just means ‘the price is increasing’ (much like when a house price increases we do not claim its ‘purchasing power’ is increasing). Similarly, given that Bitcoin is not actually in the FX market, the phrase ‘Bitcoin’s exchange rate to the dollar is increasing’, just means ‘Bitcoin’s market price is increasing’ (much like you do not characterise an increase in your house price as an exchange rate movement). The phrase ‘Bitcoin is a deflationary currency’ translates to ‘Bitcoin collectibles sometimes increase in price’ (albeit Bitcoin promoters will seldom label a decrease in its price as ‘inflation’, which they would have to do if they were to maintain linguistic consistency).

4.3. Exploiting the ‘medium of exchange’ concept

It takes a little practice, but after a while it becomes easy to tear away the monetary language that is pasted over Bitcoin tokens, and to replace it with the actual underlying collectibles language. Perhaps the most difficult phrase to translate, however, is ‘Bitcoin is a means of exchange’, which translates to ‘Bitcoin tokens are priced objects that can be swapped for other priced objects’.

To understand this you need to understand the concept of countertrade (see this article for a detailed description). If you analyse a Bitcoin ‘payment’ for say, a book, you will notice there is not – in the primary instance – a price for the book in Bitcoin. Rather, there is a money price for the book, and a money price for Bitcoin, and you superimpose those over each other to work out a residual exchange ratio between the two objects. You are not ‘buying’ the book with Bitcoin. You are countertrading, which is a practice possible with any object: consider, for example, two friends entering a clothes shop and each buying a jacket for $50. Upon returning home, they decide that they each prefer the other’s jacket, so decide to simply swap them. The friends do not claim to be ‘buying’ each other’s jackets. They just say, ‘the jackets cost the same, so we swapped them and called it quits’.

This process of clearing off money-priced objects against each other is called countertrade, and Bitcoin is notable for being very easy to countertrade, because it is highly movable. This is where its adjective armour actually does matter. Objects with high movability can become highly countertradable, which in turn can induce a certain degree of ‘moneyness’ in them. This is the strongest claim Bitcoin has to being a ‘quasi-money’, but note that its countertradability is a secondary feature induced by its primary nature as a speculative digital collectible with a price. Without that price it has no swap-ability, which means anyone who attempts to use Bitcoin’s swap-ability as a justification for its price (‘value’) has got the polarity of the situation the wrong way around.

4.4. The digital tavern

Like any priced good, Bitcoin tokens compete against other objects in the market, but – uniquely – they depend upon the Bitcoin industry promoting them as if they were competing against the dollar that underpins the markets they are traded on. The story sort of holds up because their high counter-tradability can give the illusion of them being ‘moneylike’, but make no mistake: the (sometimes) rising price of Bitcoin just means that, rather than giving dollars to a seller of some other object, a person gave them to a seller of Bitcoin collectibles, resulting in their price rising relative to the things that were not bought.

Recall the story we began with. The man in the 12th century tavern sought to give you an ambiguous ‘token’ whilst taking your ducats. If you gave him your ducats, the net effect would not be an attack on the ducat system. It would be an attack on the tavern owner, who might otherwise have got those ducats from you for board and beer. To use a more recent example, it is the promoters of Gamestop shares that lose out when people start using their disposable income to buy Bitcoin tokens from crypto promoters instead. The decision to buy either of those might be a response to an uncertain environment affected by monetary policy, but neither action is a direct ‘attack’ on the dollar, because the dollar system is the pricing hub for both objects, rather than the thing being traded.

Part 5: Giving Bitcoin a soul

Right now Bitcoin’s greatest success lies in the fact that it has mimicked the numerical surface appearance of a monetary system (whilst its promoters exploit our weakness in understanding the structure of money), whilst accompanied by a mythology that presents it as an antithesis to the monetary system. This allows it to parasite off the fears and emotions we have around the actual monetary system, whilst simultaneously tapping into people’s desire to get actual money in a ‘get rich quick’ fashion.

The deeper you look into it, however, the more circular this appears. The ‘moneylike’ nature of Bitcoin tokens depends upon their countertradability, which in turn depends upon them not actually being money, but they cannot be promoted as collectibles unless they have a monetary backstory, because in reality they are just limited edition numerical nouns with no utility in themselves.

The structure is both psychologically ingenious but deeply flawed, because – in the first instance – there is no way for anyone to come to any account of why numerical nouns will have the ability to supersede the numerical adjectives of actual money. Indeed, the main technique to do that right now is to simply make a circular appeal to the fact that the numerical nouns have a price: consider, for example, the almost messianic fixation in the Bitcoin community about how the rising price of Bitcoin tokens somehow signals a future in which those tokens will become the monetary system (rather than a thing being priced in the monetary system). The Bitcoin industry tries to convey this point by claiming that Bitcoin is undergoing ‘monetisation’, a process by which the numbers will somehow become money as people get used to them. In reality, though, they are just talking about the increase in Bitcoin countertrade.

5.1. Everyone look away

The money price of chairs stays roughly constant from one day to the next, because their utility relative to other goods stays roughly constant. Bitcoin collectibles, however, are subject to quite random alterations in price because they are numerical nouns with no inner essence, and must maintain constant buying pressure from people who do not see them as essential goods, and who mostly buy them because they see other people buying them. Much like it is easy to push a liquid up a constrained straw, and watch it drop the moment you stop blowing, limited supply Bitcoin tokens are held up in price not by any fundamental reflection on their essence, but rather by a calculated effort to pump them up whilst avoiding any reflection upon their essence.

Thus, everyone who buys in has a vested interest in not staring too hard at the object they are buying. This is why there is an army of Bitcoin promoters who focus solely on its adjectives and its rising price, whilst spinning a ‘Bitcoin as future money’ story as a marketing pitch. The promoters are not interested in describing the complex details of how such a future would unfold, any more than Coca Cola is interested in providing the emotional backstory to the characters who find themselves in its adverts. Indeed, all the promoters need to do is sustain and expand the buying pressure, which is easy to do when the media constantly helps them perpetuate the FOMO that surrounds the speculative collectibles. As they do so, those in the early buyer circles get richer in dollars by selling expensive fragments of their cheaply acquired numerical nouns to the new entrants.

In this context, the price of Bitcoin tokens will almost certainly continue to rise, and these inner holders will get extremely rich, and will continue to be big influencers. The use of Bitcoin for countertrade will continue, and crypto-capitalist promoters with humanitarian credentials will use that to pump the story in developing world contexts. As middle-class entrepreneurs in the latter countries become invested, they will attempt to sustain the buying pressure by pulling in poorer people with the ‘get-rich-quick’ narrative. Those poorer people will buy into the tokens under the belief that they offer economic liberation, and will do so under the risk of losing significant parts of their already tiny savings.

5.2. Saving Bitcoin’s inner child

Having noted this, it is important to separate Bitcoin tokens from big Bitcoin promoters. The latter are much like priests evangelising a prosperity gospel, and their entire industry rests on building two things – a trading infrastructure and a recruitment infrastructure – whilst ignoring one thing: the inner essence of the token itself. Bitcoin mining rigs always birth the same thing – numerical nouns – but the industry specialises in dolling them up with all manner of makeup to disguise that, and selling them off.

Thus, one way to metaphorically visualise a Bitcoin token is to imagine it as being akin to a lonely and orphaned child actor, pushed onto stage by managers, publicists and booking agents that surround it with a macho shell to hide its neglected child-like interior (which can collapse at a moment’s notice). But how exactly would you fill in this ‘hole in the heart of Bitcoin’, and save it from these pimps? How would my blind compatriot come to believe that a limited edition numerical noun is in fact something with a glowing inner soul, not reliant upon all that branding and pumping?

One approach is fetishisation. In anthropology, ‘fetish objects’ are objects that are granted a social power that far exceeds the utility of their body. They are created when a community generates a cultural field, within which the actual characteristics of an object are ignored, and in which it rather becomes a symbolic stand-in for social relations. Many early forms of pre-capitalist ceremonial ‘money’ (or ‘cere-money’), such as Papua New Guinean ‘shell money’, are fetish objects like this. They operate as ‘power tokens’ only when placed in the context of a community that has enchanted them (to all outsiders they just look like meaningless trinkets). Contrary to popular belief, such ceremonial ‘money’ was seldom used for commerce, but – hypothetically – fetishisation of this sort could produce a crude but unstable form of capitalist money, provided that huge amounts of effort was put into mythologising Bitcoin in the eyes of ordinary people.

There is a second approach. Some Bitcoiners are betting that the ‘inner soul’ of the numbers can be reverse-engineered by building the outer, surrounding infrastructure for moving them around. To use our earlier train system metaphor, this is like issuing out pieces of card with ‘1’ written on them, investing effort into telling everyone that they are ‘train tickets’, and then hoping that a train system will slowly appear and subsequently induce a ‘train ticket-ness’ into the card. In this way, an otherwise empty object can be ‘captured’ by a system that comes after it. Similarly, if the industry around Bitcoin loudly proclaims that it is ‘money’, whilst simultaneously heavily investing in convincing real businesses to price things in it, and real people to use it for commerce, they could – hypothetically – create a situation in which the numerical nouns become surrounded by a network that ‘captures’ them and locks them into a real economy. This remains extremely difficult, because in order to do this the entire speculative mentality (in which Bitcoin tokens generate imagery of the dollars you can sell them for) would have to be discarded, and replaced by imagery of the tokens somehow ‘anchored’ in some stable form into actual goods and services.

Right now the Bitcoiners’ greatest hope for that lies in El Salvador, where a Bitcoiner president has passed state laws trying to force its acceptance in shops. I wonder perhaps if the president himself may be heavily invested in the limited edition collectibles that his government is now promoting, but – regardless – their logic still works on countertrade. Bitcoin tokens are nowhere close to being ‘El Salvadorian currency’. They are still primarily global collectibles, predominantly priced via dollars and other major currencies, being forced by law into countertrade in El Salvador.

The hole in the heart of every Bitcoin token remains, and shows little sign of being filled in any time soon. Perhaps, however, this is a source of strength. The sheer emptiness of the token, alongside the strength of its adjective armour, allows it to carve out a shapeshifting existence in the shadows of the actual capitalist monetary system. In the end, the question that my blind friend directed towards the token – who are you? – can be answered with, I, token, am whatever fantasy you want me to be.

I finally got around to reading this awesome post, and typed up a long reply, which turned out to be too long to post here. So I posted it on my blog instead: https://ebuchman.github.io/posts/filling-the-hole-in-bitcoins-heart/

Cheers!

This is excellent :

"A vast network structure, at the centre of which lies three sets of issuers issuing out three chained layers of legal IOUs – in physical and digital form – which will later return to the issuers to be destroyed, but which in the interim entrench themselves as economic network access tokens that circulate around an interdependent web of people who cannot mobilise each other’s labour without them. These tokens are activated in the context of legal systems set within political systems set within social systems set within ecological systems, and this mesh structure underpins modern capitalism and is etched into the very fabric of our being."

- thank you!