The Luddite's Guide to Defending Cash

Why cash is a cutting-edge technology for maintaining a balance of monetary power

Note: For more progressive arguments for cash, see my Cashback series

Are you someone who is concerned about cashless society, but who finds yourself treated like a Neanderthal when you tell this to your friends? Are you worried that you’ll be labelled as a conspiracy theorist if you raise the alarm about all the data and power being transferred to the ‘cashless’ digital payments industry? Do you shy away from expressing your misgivings about the full digitization of money, out of fear of appearing like an anti-progress ‘luddite’?

If you answer Yes to any of these questions, this piece is for you. You have a right to be concerned about cashless society, and you don’t have to come across like a crackpot when making the argument for cash. In fact, you can come across as very reasonable. I know this, because I spend a significant part of my life defending cash in very mainstream circles, and I often leave people who were totally OK about cashless society feeling a lot less sure. For example, I recently debated the issue at the Brussels Economic Forum. Before the debate, the audience (which consisted of hundreds of policy wonks, economists and EU officials) was polled, with 42% being keen on a totally cashless society. By the end, that number had fallen to 27%.

Not only can you come across as reasonable when arguing for cash, but you can also come across as a lot more innovative and imaginative than the average mainstream pundit. We’re often led to believe that digital tech is ‘cutting edge’, but digital hype has been with us for over 30 years now, and is getting ever more boring and conventional. It’s far more interesting to be ahead of the curve, which means widening your imagination beyond digital fetishism.

I’d like more people to feel confident when arguing for cash, so in this piece I’m going to lay out my basic approach for you to adapt and build upon. I’ve structured this into steps, and within each I have overviews of the basic argument. I’m not going into depth on any particular sub-section (and each could be expanded out into an entire article of its own), so treat this piece as an introductory summary.

Step 1: Understand the Global Meta-Narrative

No matter where I go in the world, public and private sector officials basically say the same thing about digitization, regardless of their respective country’s situation. They will say that digital automation - and the speed, scale and interconnection it brings - is not only good, but unstoppable. This ideology is nested in another, deeper, ideology, which says that the global economy must always expand and accelerate.

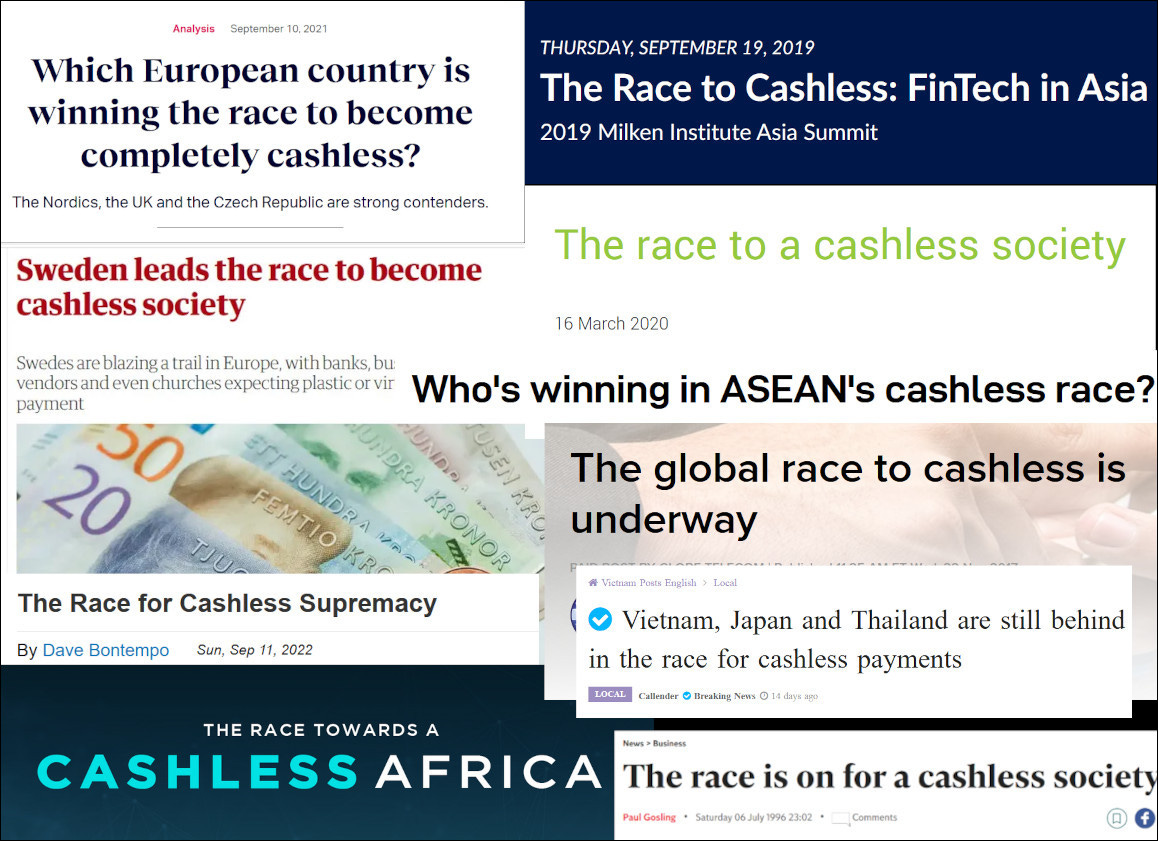

With this vision as a backdrop, we’re encouraged to then engage in a series of digitization ‘races’ (like a ‘race to cashlessness’ or a ‘race to AI’). Ideally you’re supposed to lead the way in these races by actively developing, pushing and embracing the technology, but if you have other priorities you’re told to prepare for the transition, and adapt. This vision of a race towards a pre-set destination is then complemented by three sub-narratives.

The Left Behind narrative: anyone who doesn’t want to go in the digital direction, or can’t go in that direction, is warned that they will be left behind. To stay competitive you’ll have to adapt

The Inclusion narrative: to prevent people being ‘left behind’, we find a story about digital inclusion that says that anyone who is a bit behind-the-curve needs to be thrown a lifeline, so that they can get onboard with digitization

The Delay narrative: we also find calls to give people who ‘still’ use older systems more time to adapt. The idea is to stave off the inevitable transition for a little while longer until everyone can be absorbed into the new system

We can debate where this transnational ideology comes from, but I’d argue that it stems - in the final analysis - from the corporate sector, which benefits the most from the data, scale, speed and globe-spanning capabilities that digital automation brings. The meta-narrative, and its sub-narratives, gets applied across the board to many different areas of life, but when it comes to payments it gets applied to cash.

Step 2: Understand the Payments version of the Meta-Narrative

Our monetary system is a composite system, with multiple layers of money issued out by multiple issuers in multiple forms, but through the lens of the transnational digitization narrative this nuance gets reduced to a binary between ‘physical money vs. digital money’. We then get told that there will be an inevitable transition from the former to the latter. As we’d expect from the meta-narrative, getting rid of cash is cast as a kind of unstoppable global competition, with some leading and some lagging.

This naturally then creates the imagined risk of some people (and countries) being ‘left behind’. For example, here is a UK labour party politician saying that while it is obvious that a cashless society is coming, “it is really important that we make sure we do this in a managed, careful way, making sure that nobody is left behind”, because some people ‘still’ use cash. The language reinforces the idea that cashless society is like an unstoppable weather event that’s approaching, and that some people will need temporary shelter from it. This message gets endlessly replicated in media.

This is turn creates the inclusion narrative, in which various parties say that we must rescue those who may be left behind. I remember being on a show with a Citigroup executive who was asked what the greatest risk of a cashless society was. His answer was ‘ensuring full inclusivity’. In short, he thought the greatest risk was that not everyone would be absorbed into his bank’s (and other banks’) systems. After all, a ‘cashless’ society is a society where you have to use cards and apps provided by the banking sector. To remedy this risk, he suggested that banks and governments must work together to onboard people into the system. It’s a bit like a McDonald’s executive saying that the greatest risk of McDonald’s is that not everyone has a McDonald’s close by, and that the state should help McDonald’s extend its services.

2.1) The ‘Upgrade’ mentality

Many people don’t realise that when they present cashless society as inevitable, they simultaneously are presenting banking sector domination as inevitable. But not only is this bank dominated society supposedly unstoppable, but we are told that it’s better. It’s presented as an upgrade to our existing system.

Upgrades generally are seen to only improve our lives without detracting from them. Email is an upgrade to the fax machine because it achieves the same function but more efficiently and adds new capacities in the process. The car is an upgrade to the horse-cart, because it replaces the horse and cart with an engine and a metal cabin, and adds far more control and speed.

In the monetary system, this ‘upgrade’ narrative is applied to cash. Cash is cast as the payments equivalent of a horse-cart, and once placed in this position there are three categories of insults that get thrown at it:

Oldness: it is outdated, archaic, stuck in the past

Inefficiency: it is inconvenient, hard to move, slow, and costly in various ways

Dangerous: it supports social evils like tax evasion, crime and disease

This demonised version of cash is then set against a romanticised version of the digital money that you control with cards and apps, which is said to be:

New: current, modern, up-to-date, cutting-edge

Efficient: convenient, fast, cheap and globe-spanning

Safe: free from muggers and thieves, clean, transparent

This framing is so prevalent that even apparently critical thinkers struggle to see through it. I’ve done a huge number of interviews on this topic, and I’ve lost count of the times when the interviewer has framed their questions as if I’m on a well-meaning but futile crusade to save horse-carts from cars. This is because they have the meta-narrative ideology installed in their minds. Fortunately, there are four effective ways to jam that ideology. In this piece I’ll cover the first two, and in the next piece I’ll cover the remaining two.

Step 3: Understand the Casino-Chip Society

One of the crucial rhetorical tools used by anti-cash proponents is to make out that there is but one type of money in society, but that it comes in better and worse forms. Think about a traditional piano versus an electric piano: they are both pianos, but one is much easier to fold up and carry around. In our minds, we have ‘piano’ as a single category, and then we imagine different versions of it.

People often think of money like this too: cash and the units in our bank accounts are presented as being - at a deep level - the same thing, and both get filed under the single category of ‘money’ in our minds. We then imagine that the same thing has a physical and digital form, with the latter - according to the upgrade mentality - being supposedly easier, safer, and more advanced.

This framing is wrong, and shows a lack of knowledge about the actual structure of modern monetary systems. I’ll explain this below, but the summary is as follows: Even if you do believe cash is old, inefficient, and dangerous, it structurally underpins the digital systems that you think are so new, efficient and safe.

You don’t need a degree in finance to understand this. All you need is a good metaphor, and here it is: the units in your bank account - which you use when you are paying digitally via app or card - are not government money. They are digital casino chips issued out by banks. I wrote an entire piece about this a few months ago, which you can find here:

The Casino-Chip Society

Many people believe that their national currency is a single currency, but that it appears in different forms. A person comparing a dollar bill with a dollar bank account balance may believe those are just different versions of the same thing, like comparing an acoustic guitar with an electric one, or a physical train ticket with a digital one.

I encourage you to read that piece, because it will tell you everything you need to know about the layers of money in our society, and their different issuers, but the crucial points are these:

If I hand government-issued cash to a casino, they take ownership of it and issue me their own chips in return, which can be passed around in the premises. Those casino chips only have power because I believe I can take them back to the cashier to redeem them for cash

Similarly, when I hand government-issued cash to a bank, they take ownership of it and issue me their own ‘digital casino chips’ in return (which are the digital units I see in my bank account). These can be passed around the bank payments system via card and app, but these digital units only have power because we believe that they can be redeemed for state cash. Going to an ATM is much like going to the cashier at a casino, and asking to ‘cash your chips’ so you can exit

This leads to two immediate issues, both of which are seldom appreciated in cashless society debates:

Legal: If a casino refused to redeem my chips for cash, I’d sue them, but what if my bank closes down its branches and ATMs to stop me cashing out my digital chips? They are basically saying ‘you cannot exit our systems’, or alternatively ‘you have no right to exit our systems’

Financial stability: An unredeemable casino chip is a dodgy casino chip. An unredeemable bank-issued ‘digital casino chip’, similarly, is an unstable and dodgy form of money, even if it gets moved around via a flashy and secure app. Ironically, as the public cash system is undermined, our confidence in the private digital systems risks being undermined too (incidentally, this stability concern is a major reason why governments are experimenting with ‘digital cash’ or CBDCs)

This may seem a little technical, so let me repeat the takeaway point: Even if you do believe cash is old, inefficient, and dangerous, it structurally underpins the digital systems that you think are so new, efficient and safe. Digital money is not an ‘upgrade’ to cash, because it derives its own power from cash. If you don’t believe that, watch what happens every time the banking sector looks shaky, or a crisis looms: cash withdrawals spike.

Step 4: Understand the consequences of Uberfication

If Step 3 points out that cashless systems depend on cash, Step 4 goes further by challenging the idea that they are safe, efficient and positive. As mentioned earlier, we often find a demonised version of cash pitted against a romanticised version of digital. Cash is presented as the ‘horsecart of payments’ trying to compete against the futuristic ‘sportscar’ of digital payments.

To rebalance the debate we need to highlight the negatives of digital and positives of cash, and to do this we need to reframe the metaphor. Here is how you do it. Cash is not the horsecart, and digital is not the car. Rather, cash is the bicycle of payments (or mountainbike), while the bank-issued casino chips we use for digital payments are the Uber of payments.

The first thing that this new metaphor helps us understand is that convenience is not an absolute: If I ask someone ‘is a bicycle or Uber more convenient’, it’s an abstract question, because they are both convenient in different situations, because they optimise for different things. Let’s isolate two classes of difference between them, which give rise to their unique characteristics:

Autonomy vs. Dependence: With a bicycle, I directly control it. With Uber, I’m relying on a third party. Similarly, with cash, I directly control it. With digital payments, I’m relying on a whole series of third parties.

Public vs. Private: Bicycles only require public infrastructure, whereas Uber relies on a private corporate infrastructure that runs on top of public infrastructure. Similarly, cash is a public utility, whereas paying for things with digital casino chips involves becoming dependent on private corporate infrastructures (which, as we saw in the previous section, are built on top of the public money system)

4.1) The healthy balance of power

If you like using Uber, do you have to stop using bicycles? Obviously not. If someone tried to force you to choose between only having one or the other, you’d resist, because they should co-exist. The mere fact that we have newer digital things doesn’t mean we request to have no analog things. This is very easy to confirm by asking anyone these two questions:

Do you want the ability to use Uber? (Many people answer ‘Yes’)

Do you want public bicycles lanes to be shut down if a critical mass of people download the Uber app? (Almost everyone answers ‘No’)

In fact, the only people likely to answer Yes to the last question would be certain parts of industry (such as Uber or the auto industry) that would benefit from the shut-down of bicycle lanes. Now ask someone the same set of questions about payments:

Do you want the ability to use digital payment? (Many people answer ‘Yes’)

Do you want the right to use cash to be taken away from you? (Most people answer ‘No’)

The reason people answer like this is that they wish for choice. The digital payments industry, by contrast, would prefer a lack of choice. They’d benefit if we became completely dependent on their systems, but if that actually happens, the balance of power between between autonomy and dependence, and public and private, would be radically shifted.

Balance of power is a very important concept in systems analysis. Not only are there serious political consequences if one industry, party or technology dominates a system, but there are also serious implications for the resilience of that system. For example, we may find lifts in a skyscraper useful, but it would be extremely short-sighted to get rid of the stairs. Nobody conceives of stairs as being ‘out of date’, simply because they’re an older and slower form of vertical movement. They are perennial and classic (or, to use modern slang, OG). In fact, despite all the rhetoric about cutting-edge technology, our society is full of perennial classic stuff, and many people love it. Our society is much better off when we maintain balances of power between newer and older.

4.2) The unhealthy balance of power

Let’s extend this transport metaphor. The marketing spiel of apps like Uber promise you a slick experience and convenience, but come at the expense of you relying on the corporation. Most people don’t mind having moderate dependence on institutions like this, but total dependence is a recipe for extreme centralisation of power and erosion of autonomy. As a thought experiment, imagine if all forms of transport except Uber were removed from our society, resulting in total ‘Uberfication’. What would happen in this ‘convenient’ society?

For a start, you’d notice that your entire ability to move depended on an institution. While the first few weeks of trips might not bug you, over time it would begin to feel deeply stifling, even oppressive. The mass dependence on a intermediary would not only transfer mass power to Uber, but would in turn unlock a host of other problems:

Privacy: your every single movement would be recorded in Uber’s datacentre, along with a host of other data, in effect creating mass surveillance of all movement in society

Censorship: Uber would have the ability to stop your movements, or place limits and conditions on them (e.g. ‘you are allowed to go here at this time, but not here at this time’), if it decided to do that, or was ordered to do that

Exclusion: anyone who struggled to use the system, or who objected to using the system, would not be able to move

Resilience: even if the company tried to serve our best interests, any failure in its systems - via hacking, bugs, power outages, cyber-attacks etc - would cause the entire society to grind to a halt, literally

Centralisation tendencies: in a totally Uberfied society, there really would be no such thing as a ‘local economy’, because the smallest local movement would only be possible if it were first routed through a distant central player. The driver could be your old friend from next door, but you’d have to go via Uber, which will take rent from your relationship

Cultural vibe: that intermediation process changes the entire feeling of your society. For example, teenagers of old could skirt around authorities by racing around on bikes and skateboards, but the new crop would have to try live out their rebellion while being constrained in cars monitored via GPS

This thought experiment is deliberately extreme, in order to help us quickly identify the main classes of problems that emerge from any societal dependence on digital infrastructures. Let’s now use this Uberfication metaphor to see the negative sides of digital payments - which are controlled by an oligopoly of Big Finance and Big Tech players - and the positive sides of cash.

4.2.1) Resilience vs. lack of resilience

Cash doesn’t crash. Digital payments, by contrast, run through centralised systems that can fail. If everyone is dependent on them, this creates an incredibly serious point of weakness that can cause sudden disruptions to our lives. Digital infrastructures are vulnerable to:

Cyber-attacks

Hacking

Outages through error, negligence or bugs

Outages through disasters and extreme weather events

The latter is of special concern in a era of global warming. Also, despite all the digital hype (and perhaps because of it), digital infrastructures face resource shortages (e.g. rare earth metals), and hardware shortages (e.g. semi-conductors). Also, much digital fetishism is built on the assumption that we’ll have no future constraints on energy to power mass computation, but it’s more prudent to prepare for a future in which you can withstand energy shortages.

4.2.2) Inclusion vs. exclusion

As mentioned earlier, the threat of people being ‘left behind’ during the supposedly ‘inevitable’ takeover of digital systems is one of the things used - perversely - to try accelerate the spread of those systems via ‘inclusion’ initiatives. Rather than accepting that narrative, we should be fighting for a balance of power, but if the balance of power was totally shifted then it would indeed be true that there would be huge issues of exclusion for all those:

Who lack the ability to use digital payments systems

Who don’t want to use the systems

Who are deliberately prevented from using the systems

The only means of survival in a capitalist economy is via exchange, and money is what we use for exchange, so if all payments have to go through a set of centralised institutions, they can wield enormous power to decide who gets to exchange on what terms. This is why digital payments are a vector via which to exert control, censorship and discipline. Cash, by contrast, is inherently inclusive, because it is a ‘bearer instrument’ that requires no account and no specialised knowledge to use, and once people have it, you cannot block them from using it.

4.2.3) The Four Sub-Balances of Power

Cashless society disrupts the balance of power between autonomy and dependence, and public and private, but this leads to four more imbalances of power.

1) Privacy vs. Surveillance

There is nothing wrong with moderate degrees of transparency in a society, but total surveillance violates our rights to privacy. The data derived from payments is huge, and empowers three entities:

Big Brother: governments that want to watch you

Big Bouncer: corporate institutions that use your data to decide whether you get access to things or not

Big Butler: corporate institutions that use your data to steer you, curate your world and manipulate you

2) Localisation vs. Centralisation

In a cashless society, even the smallest local economic interaction benefits Big Finance and Big Tech. So, even if you are under the belief that small local businesses can cut some costs by ‘going cashless’, this comes at the expense of a massive net power transfer to centralised corporations, which negatively impacts the structure of our economy as a whole. If you’re interested in maintaining a degree of diversity and localisation in your economy, then cash - which is inherently local in its circulation, and which yields no fees to an oligopoly of distant central players - is crucial.

3) Textured vs. Frictionless Interaction

We are always told - in accordance with the transnational acceleration ideology - that making everything frictionless is good. In reality, human beings like a balance. We are tactile, and we enjoy engagement with our surroundings, and many things cast as ‘friction’ in a capitalist system are actually things many people enjoy, such as talking to someone at a shop. ‘Frictionless’ digital payments literally accelerate our spending by up to 40%, precisely because they are designed to not be noticed or felt (here are ten studies that show that), but friction can actually be very useful in payments. One major reason why cash is historically favoured by low-income communities is that its tactile nature is much better for intuitively budgeting and avoiding indebtedness. You can see how much you have, and feel the loss of it when you let it go. Incidentally, from an accessibility perspective, the literal friction - or texture - of the raised markings on banknotes are vital for blind people to feel what they’re using.

4) Informality vs. Formality

What’s the cultural difference between a cashless hipster cafe and a cash-only canteen? The former has a far higher level of ‘formalization’. Formalization refers to the process by which large institutions begin to intermediate between small players. In the case of the cafe, Apple, Visa, MasterCard, and the banking sector all now mediate between you and the owner, whereas in the canteen, the interaction is just between you and the owner.

In mainstream circles, down-to-earth ‘informal economies’ are often demonised, and seen to be dirty zones of poverty and crime. There is a major class element to this, because a lot of poorer communities have low trust in formal institutions and often prefer to work through networks of informal relationships, but even in middle-class society most people like a balance between informal and formal. A society with too little formalization can be chaotic and frustrating, but a society with too much can feel paternalistic, sterile, commercialised, oppressive and even inhuman.

This leads to one of the hardest points to convey about cashless society. It is a formalization process by which large institutions get between our economic interactions, which means it’s accompanied by a change in the feel or vibe of our society. As Visa and MasterCard insert themselves between every act of exchange, everything starts to feel more gentrified. Zones of informality that we actually treasure - such as giving your kid pocket money, or playing a simple game of poker at home with your friends, doing a garage sale, or competing in a pub quiz with a small monetary prize - now all have to be incorporated into a formal economy that’s presided over by large institutions. Cash, by contrast, protects us from total formalization.

Coming up in Part 2

Step 4 is designed to show us that cash has a crucial role in keeping the dark side of digital money in check, and that in the absence of cash that dark side would really get to express itself. This goes a long way towards rebalancing the debate, but it’s wishful thinking to imagine that anti-cash proponents will give up. In my experience, they try to neutralise the Balance of Power arguments by cherry-picking single negative elements of cash, and then presenting those as if they were a killer argument to get rid of the balance of power entirely. In Part 2 we’re going to train ourselves to fight off these single-issue insults and accusations thrown at cash. I’m also going to show you how to derail the typical account of why cash is in decline, through a simple visual model. Finally, we will look at the steps required to bring about a revival in cash. I hope you enjoyed the piece, and please do use the comments section to make suggestions for additional arguments that can be added.

It's point 4 that finally answers the question in a way that can be used in the pub. the bike/uber analogy, I think, nails it. other analogies (such as lift/stairs) are also helpful.

Right on target Brett! If we allow cash to fade out of use it’s never going to come back. Society needs to think deeply about the consequences for the less affluent and about the powerlessness of the individual in an entirely digitally controlled world.