The Whale of Mass Destruction

How a fundamental weakness in Bitcoin might (technically) crash our economy

Audio version for paying subscribers here!

Greetings citizens of ASOMOCO! Occasionally I like to wade into a more complex topic, and today’s piece is a long-read that might appeal to the more finance-minded among you. I’d encourage non-experts to give it a go, because it has real implications for our lives, and also because it concludes with predictions about the Trump administration’s future relationship to crypto. Enjoy!

When I used to work in finance, we’d talk about two different types of trading -fundamental and technical.

A fundamental trader is someone who looks out into the world to assess something. Picture yourself as a 14th century merchant on the Silk Road in Central Asia. Imagine closely studying the farmlands you pass, or asking local innkeepers what their patrons are saying about the quality of the cotton harvests. You’re a detective, speaking to people on the frontlines of production. You verify stuff.

In the financial markets, the fundamental trader is represented by someone like Warren Buffet. Ok, he’s not really considered a ‘trader’, because he holds investments for the long term (and ‘trader’ tends to refer to a shorter-term mindset), but he’s the kind of guy who’d actually study what a company is doing. He’d assess how many widgets they’re selling in what country, how profitable that’s likely to be in the future, and whether that future profitability is reflecting itself in the present price of their shares.

A trader using ‘technical analysis’, by contrast, is someone who watches other traders to make assessments. It’s like a guy on the Silk Road who studies the other camel caravans for clues. How many of them are heading in what direction to what market, and what are they carrying in what volume?

In the financial markets, watching other traders takes the form of studying graphs that show volume of trading, price changes, market depth and various other metrics. Generic stock photography of traders always shows this. Type ‘trading’ into a Google image search and you’ll be inundated with images of people at computers staring at ‘candlestick’ graphs.

Analysing such a graph is, de facto, the process of watching other traders on the financial Silk Road, but this practice is rife with pseudo-scientific jargon that attempts to present this as akin to studying physics. If you ever hear a person using terms like ‘resistance levels’, ‘moving averages’, ‘oscillators’ or ‘on balance volume’, they’re doing technical analysis.

A typical financial market - whether blue chip shares, corporate bonds or oil futures - will have both of these types of traders. They will, however, rely upon a foundation of fundamental analysis.

For example, in a stock market, it’s going to be assumed that all the ‘whales’ - aka. the huge institutional buyers of huge chunks of shares, such as the giant pension funds - are going to be doing fundamental analysis. The technical traders are assuming that at least some of these players that they’re watching are watching the real world, imparting some rationality into the market.

In fact, if the level of pure technical analysis gets too high, your market can lapse into circular self-reflexivity. Imagine if every single trader on the Silk Road was simply watching the other traders, leading them all to wander aimlessly in the desert. If technical traders are basing their actions off other technical traders, who is to say that they’re not drifting into mirages of delusion?

Typically, we call those mirages bubbles.

Now, I’m not saying that every technical trader is an idiotic herd-follower - some are indeed very sophisticated. If, however, too many traders have entered markets for reasons other than rational assessment of what’s actually happening on the ground, share prices can detach from what their ‘fundamentals’ actually suggest.

Historically, though, this detachment from reality provides lucrative opportunities for more cool-headed traders to come in and bet against the delusional market. For an entertaining example, watch Steve Carrell’s portrayal of Steve Eisman in The Big Short, who bets against the mortgage-backed securities market after investigating the underlying loans, housing and tenants.

Alternatively, when prices drop through panic to levels not justified, people like Warren Buffet come swooping in to pick up cheap deals at fire-sale prices. Theoretically, bubbles and busts will be moderated by these more sane investors, who pride themselves in seeing through the irrational exuberance or depression.

The fundamental-less market

This brings us to Bitcoin. Perhaps the most notable feature of the Bitcoin market since its inception has been the almost total absence of a class of true fundamental traders.

When Bitcoin was first released, there was no ‘market’ for it. It was simply a branded digital token that could be moved around. If you tried to sell it, most people would look at you and ask ‘what is it?’ It took a while for a dollar price to form, but even when that happened, few buyers had any strong idea of how to justify the specific price they bought at.

As the cultural hype around it grew, newly established crypto traders tried to figure out models that could explain - from a fundamental perspective - why Bitcoin was priced at X, Y or Z. Was there some deep fundamental reason it suddenly went up by 34%, and then crashed by 18% the week after? Were these price changes driven by a class of market detectives who were investigating the real world conditions that would rationally point to such sudden changes?

Well, the answer is no. It was mostly random, driven by guess-work and surges in market hysteria or depression.

Prices in any market go up if buying pressure is higher than selling pressure. In fundamental analysis, though, it’s assumed those pressures have some external referent that can be studied. For example, if a share goes up or down by 40%, it should mean some very big event has happened in the real world to affect the company’s future.

When asked to account for the price change, you cannot just say ‘prices are going up because more people are buying’. You have to account for why they are buying, and saying something like ‘they are buying in anticipation of others buying’ is highly dubious, because you’ll in turn have to account for why these others are buying. If those others are buying in anticipation of that same thing, your market is in a state of self-referential delusion or faith. That’s not a rational model.

So what is a rational model? Well, a financial contract like a share or bond has a theoretical ‘fair’ price, because it’s a legal contract that guarantees the holder a cut of a whole series of future cash flows. In the case of bonds these are interest payments, and in the case of shares they’re dividends.

The Finance 101 method to work out the fair value of a share, for example, is to guess the future revenues of a company and subtract from that the predicted future expenses, which leaves you with a whole series of estimated future profits. You then take those and ‘discount’ them, which is like shrink-wrapping them into the present to account for the time and risk it will take to reach them. This leaves you with a theoretical ‘fair’ price, which you can then compare to the actual price in the market, so that you can make your trading decision.

Now, this isn’t perfect, because the world is chaotic and you cannot perfectly guess what the future profits will be - hence the wide divergence of opinion on the correct price of a share - but at least there’s a theoretical model. The arguments about the share price of mining giant Rio Tinto, for example, will involve real world things, like what the global demand for aluminium will be in future, which in turn requires estimates of aluminium consumption in - say - the construction and aerospace industry.

What, though, is the theoretical model for pricing something like Bitcoin?

Well, the reality is that there’s really no ‘rational’ model for assessing whether a Bitcoin token is under or overpriced. The reason for this is that a Bitcoin token is a limited edition digital object, not a financial contract.

The fundamentals of Bitcoin

The job of a fundamental analyst is to ignore the hype being pushed out by promoters, and to assess something from scratch. For someone like Warren Buffet, it’s not good enough to say something like Bitcoin represents freedom from oppressive states, or Bitcoin will save us from inflation. Taking those statements at face value is just a form of faith (just like a person might uncritically accept a sales pitch from some dodgy stockbroker in The Wolf of Wall Street). I mean, it hypothetically is possible that the pitches are true, but you can’t just assume that.

So, let’s ignore the Bitcoin hype-machine for a moment and ask some very basic questions.

Firstly, what does holding a bitcoin token give you? Hmm, in itself, kinda nothing. I’ve held Bitcoin, and I can vouch for the fact that it just sits there in your digital wallet. There are no dividend or interest payments attached to it, and it gives you no voting rights in any enterprise. It’s like holding a bar of copper, except that Bitcoin is a digital object with no industrial use.

Ok, so what can we say about the object? Well, it’s a digital collectible that has a limited supply, a decentralised transport system for moving it around, metallic branding pasted over it, and a highly vocal community that chants stuff about it. I’m going to ignore that latter community for now, because they are - at least initially - just a distraction to the fundamental trader.

Let’s delve deeper into those somewhat sparse fundamentals. The digital collectible itself is just a number written out after the decentralised clerks (‘miners’) that maintain the transport system expend energy (technical note: unlike the numbers written out in the banking sector, these numbers don’t represent a liability to an issuer - aka. they are not a form of ‘voucher’ that can be redeemed).

There’s a hard limit placed on how many of these numbers can be written out in total (21 million), but once ‘mined’ or ‘minted’, you can perform mathematical operations on them, like splitting them and passing a piece to someone else. These movable numbers are attributed to particular addresses and woven into a timeline that acts like a massive account database. Once replicated and distributed across a network of peers, this timeline becomes largely unchangeable by central parties, giving the numbers the feeling of being ‘censorship resistant’.

These numbers get called ‘tokens’, and they have come to have a US dollar price, and given that you can pass them around, you can use their dollar price to engage in something called countertrade. Countertrade is the process whereby you use the resale price of one thing to ‘buy’ something else of equivalent price. You can do this with any priced good in the entire world - from bags of wheat to vintage records - but Bitcoin happens to be highly countertradable (see The Art of Crypto Kayfabe).

This is what people are doing when they claim to ‘buy’ goods and services with Bitcoin. They’re paying for, let’s say, a camera, with the US dollar resale price of Bitcoin (to see why this is easily empirically verifiable, see this footnote1).

Given that the token is highly movable and branded with monetary imagery, however, countertrading it loosely feels ‘money-like’ (unlike, for example, if you were using vintage records to engage in the same process, which would feel more like ‘barter’).

This, however, is totally dependent on the dollar system in order to work: if Bitcoin was priced at $0, it would cease to have counter-tradeability (aka. nobody is giving you a camera for a digital object that cannot be resold for dollars).

Circular faith as a source of strength?

Many people have tried to use the above fundamental features of Bitcoin to make claims about its fundamental strength. This, however, often leads them into tangled webs of circularity.

For example, a person believes that Bitcoin should have a US dollar price because its exchangeability (aka. counter-tradability) is useful for bypassing the bank payments system. From one angle they are correct - countertrade is indeed useful. But, Bitcoin’s counter-tradability is an emergent phenomenon based on its US dollar price, so relying on appeals to that phenomenon to justify that price is circular and shaky as hell.

Here’s another example. Someone says that it’s the censorship resistant nature of the transport system that gives the tokens value. This is like saying that it’s the train tracks that give the cargo on a train carriage value. They’re basically saying: the thing I’m moving has value because it can be moved securely without interruption from authorities. What is that supposed to mean? I’d agree that, without the train tracks, a cargo might not end up being useful to an end user who needs it somewhere, but it’s not the tracks that are imparting the value.

Here’s another classic: Bitcoin is valuable because we use loads of energy to produce and secure it. This is like saying that a car, a water bottle, a haircut, or a giant statue of Stalin is valuable because people had to use energy during the production of those things. Every act of production in the world uses energy, not just Bitcoin. I could expend an enormous amount of energy creating nuclear waste, and I might build a highly secure system for moving it around, but that does not imbue it with use value. For more on why this argument is bullshit, see this footnote2.

Ok, but what about using more cultural factors as a basis for strength? For example, gold has a huge and resilient market, and a large part of that is based on a historic fetish for the colour and texture of the polished metal. In fact, actually useful metals tend to get called ‘base metals’ and are less culturally valued, while ‘precious’ metals are associated with vanity, status and religious ritual.

Could Bitcoin be like a ‘precious’ digital object?

Hmm… well beyond its branding, Bitcoin is of course colourless and textureless binary code, so it’s not going to compete on sensory desirability. Could it, however, come to have cultural weight through - for instance - its edgy story? Could it be that some see a certain beauty in the elegance of the cryptography it utilises? Perhaps people feel a sense of mystique around it due to its mysterious founder? Certainly, politicised mysticism could be the basis for a strong community to form, and they might attach their self-identity to the object, and - in turn - have an ongoing desire to buy it in order to affirm that identity.

So, my fundamental analysis must eventually lead me to that chanting community that surrounds the object. I might, for example, study the phenomenon of HODL culture in Bitcoin. HODL is a contraction of ‘hold on for dear life’ (and originally a misspelling of the word HOLD). HODLers are a cultural group who dedicate themselves to never selling Bitcoin, and to only buy it. HODL culture comes along with memes about the strength of the hands that hold on - such as ‘diamond hands’ to refer to exemplary HODLs who hold at all costs.

To a typical financial trader, such behaviour is very alien. HODLing, as a cultural principle, involves no fundamental analysis, or even technical analysis. It’s just a pure faith that the price will go up as long as you hold on. Of course, if such a cultural movement embeds itself, and begins to grow, that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, because every new HODLer is taking supply off the market, putting upwards pressure on the price.

So, if I had some metric to measure the spread of this memetic movement, I might be able to calculate how this would affect the overall price over time. That would be a form of ‘fundamental’ analysis… or at least analysis of fanatical fundamentalists.

In reality, though, that’s a weak metric. Bitcoin has no sensory characteristics (i.e. it doesn’t look, taste, smell or sound like anything, and cannot be stroked), so to build a strong culture out of it the community either has to resort to quasi-religious imagery (as if it were a supernatural entity), or political appeals. After all, most religions are based on an ineffable empty centre, an article of faith that can never be proven or disproven, and religions can be very strong and lasting.

The appeals being made in HODL culture, though, aren’t really about spiritual transcendence. They’re about US dollar gains, which kinda takes away from the sense of reverence. Those gains can be given a political spin, but I suspect that a lot of the supposed HODLers are actually quite flaky. Given this lack of true fanaticism, our fundamental analysis must assume that HODL culture could very well collapse into DRPO - ditch, run, pull out - culture very quickly.

HODL vs. FOMO culture

Beyond HODL culture, though, what is the model most people are using when they buy Bitcoin? Well, it’s pretty simple. Their model is ‘I’m assuming that many more people will be trying to buy it in future when I’m trying to resell it’.

This is a flawed model, because those people in the future are going to be thinking the same thing. There’s very little recourse to fundamentals, and this is the reason why Bitcoin sometimes gets accused of being a ‘Ponzi scheme’.

In reality, Bitcoin is not a Ponzi scheme. A true Ponzi scheme involves a sham investment company telling you that you’ll get great returns if you invest your money with them, but then taking your money and giving it to earlier investors (which then appears to fulfil the sales pitch in the eyes of those early investors).

The vibe of a Ponzi scheme, though, is one in which new people are required to give older investors their returns, and this vibe does correspond with a lot of the behaviour of the crypto industry. Given that there’s no true ‘fundamental’ way to convince people of what the price of the tokens should be, the only thing the industry can do is assure us that ever more people will be coming in, and that we must get in before them, lest we miss out. Below, for example, is an ad I saw in Berlin earlier this year. Translated, it means ‘why didn’t I invest in Bitcoin?’

From a fundamental analysis perspective, this marketing approach is worrying. It tells me that the industry is relying on FOMO, rather than appealing to some real world fundamentals.

Perhaps, however, the spread of FOMO can be treated as a kind of measurable ‘fundamental’ cultural factor, much like the spread of HODL culture. It’s certainly very possible that the price of Bitcoin could be pushed up a lot more if ever more waves of people are convinced to come in through FOMO.

That said, even in a global population of eight billion people there are ecosystemic limits to how many people are prepared to expose themselves to this object for any length of time. After all, most people need to live, and even if they do hold fragments of Bitcoin as a FOMO ‘investment’ for a period, they need to liquidate it at some point to pay for groceries.

To predict the effect of FOMO, a fundamental analyst needs five pieces of empirical evidence, as follows: what percentage of the world has been exposed to the viral narrative, how susceptible are they to it, what are their savings, what percentage of those savings are they ever likely to put towards buying up Bitcoin, and how long will they hold it before they start selling?

Understanding those metrics over time might start to give you some basis for mapping the price, but FOMO always relies on at least some vague sense of an underlying story, so understanding this shifting buyer base also involves mapping how the story has shifted over time.

Choose your own crypto-adventure

I was involved in the early Bitcoin community, and at that time they were still using the original story, which was that Bitcoin was a monetary system designed to destroy the US dollar and the financial sector. There were limitations to the appeal of that story, but those were soon overcome by re-characterising Bitcoin as a money-priced asset you could invest in to get better US dollar returns than shares.

Over time a whole proliferation of new justifications came out. It’s been cast as a way to save people in weaker countries from inflation, or to bring about a new golden age for powerful countries like the USA. It’s been pitched as a way to solve climate change by regulating the energy grid, and as an anti-woke way to stick-it to social justice warriors who care about climate change. It’s been imagined as the ultimate attack on states, and as the ultimate securer of America First state power.

The narrative is inherently flexible - like a ‘choose your own adventure’ book - because the thing you’re dealing with is a limited edition movable secure digital object that has no characteristics other than the fact that it’s limited edition, movable and secure. All the claims made about it are essentially unfalsifiable, because they can always just be deferred into the future - in future it’s going to be the new currency.

This cargo-cultish vibe originally irritated elite financial sector traders. To get a job as a Goldman Sachs trader, for example, you had to actually prove that you could do some form of rational analysis. Simply jeering and ranting didn’t cut it. The crypto industry, though, has heavily showcased its scruffy ‘unprofessional’ story, to prove that it’s a kind of ‘everyman’ form of populist finance that stands in contrast to the elites. Ha, those investment bankers and university professors are scoffing at you. This means you’re on the right track!

The crypto industry has always relied on appealing to the proverbial ‘man in the street’ rather than the professional trader, and this is why it borrows heavily from the day-trading industry, which uses exactly the same marketing strategy. The most interesting political moment for that industry was the meme-stock manias of 2021, in which armies of small day-traders were imagined to take on the giant hedge funds that really control the financial markets.

Needless to say, the crypto industry has leaned into both the libertarian political philosophy embedded in Bitcoin’s design, and a nihilistic ‘degen’ culture which sneers at sophistication. It turns out that this combo is quite appealing to a certain young male psyche, and that same psyche was also susceptible to being pulled into the rhetoric of the Trump campaign, with its seemingly rebellious and revolutionary middle finger up to the ‘liberal elite’. This is why the crypto industry and Trump entered into an alliance. To use YouTube language, they did a collab to expand their respective subscriber bases.

Unrealized gains from unrealized patronage

Trump is a political entrepreneur, and if entrepreneurs like to create new markets, political entrepreneurs like to create new constituencies. He (and advisors like Bannon) has been skilled at tapping into various feelings of discontent among disparate groups, and focusing them all on an apparent common enemy.

This enemy - which we might generically label the ‘liberal elite’ - is some strange Frankenstein that can unite a motley crew of anti-woke social conservatives, very online young men, rust-belt workers, Christian evangelicals, old anti-corporate activists, anti-vax wellness influencers, anti-environmentalist oil industry execs, anti-immigration nationalists, and so on.

The ‘liberal elite’ ranges from journalists investigating corporate abuse through to big tech shareholders, broke university students, Roman history professors, neoliberal financiers, musicians, actors and corporate execs. The Trump administration includes many of the latter, but this inconsistency doesn’t matter because it’s the spectacle that counts. It’s the kayfabe, the staged extravaganza that people enjoy.

The point though, is that a movement built in opposition to a Frankenstein enemy will be a Frankenstein in itself, and Trump has to feed it because he wants his creation to love him. To achieve this he hands out patronage. Since taking office he’s been ticking through a laundry list of actions designed to try to please each constituency.

This is tricky, given that automation lords like Musk are diametrically opposed to, for example, transport workers threatened by automation. Part of the thrill of ‘deal-making’, however, is somehow to align all these groups through a series of hacks. Trump takes pleasure in attempting to centrally plan the global economy, like getting the Chinese government to agree to buy soybeans from his farming base in exchange for being released from certain tariffs, and so on.

The crypto industry is a Trump constituency that has yet to fully receive its reward, and it also offers potential for those hacks that Trump enjoys. For example, the crypto industry has long pitched crypto speculation as a way for the everyman to get rich, and this is a convenient story for a conservative government that wants to gut the social security system that the everyman might also rely upon.

This goes a long way to explaining the alliance between Trump and the crypto industry, who poured a huge amount of money into his campaign. This alliance has been strengthened by the fact that Trump’s sons have been staking out a heavy position in the industry (avoiding claims of gross nepotism by claiming that they’ve been blocked by the liberal elite from other means of getting enormously wealthy).

Trump and Melania also cashed in on their crypto supporters by selling them memecoins, but - beyond some sense of euphoria at an impending new golden age - people are buying into such coins because they believe that Trump will order a massive liberalisation of the crypto industry, and one that will indirectly hand out patronage in the form of higher prices.

This promise was explicitly built into Trump’s election strategy. He touted the idea of the so-called ‘Crypto Strategic Reserve’. This would involve the biggest whale of them all - the US government - strategically manipulating the crypto market by buying up the limited edition tokens, under the pretence of securing national interest (as if Bitcoin was like oil).

That plan hasn’t materialised in any meaningful sense yet. In fact, there’s a latent sense among the crypto community that not enough patronage has been handed out, and that more actions are probably forthcoming once Trump is done with his other projects. Big investors are strategically lining up in anticipation.

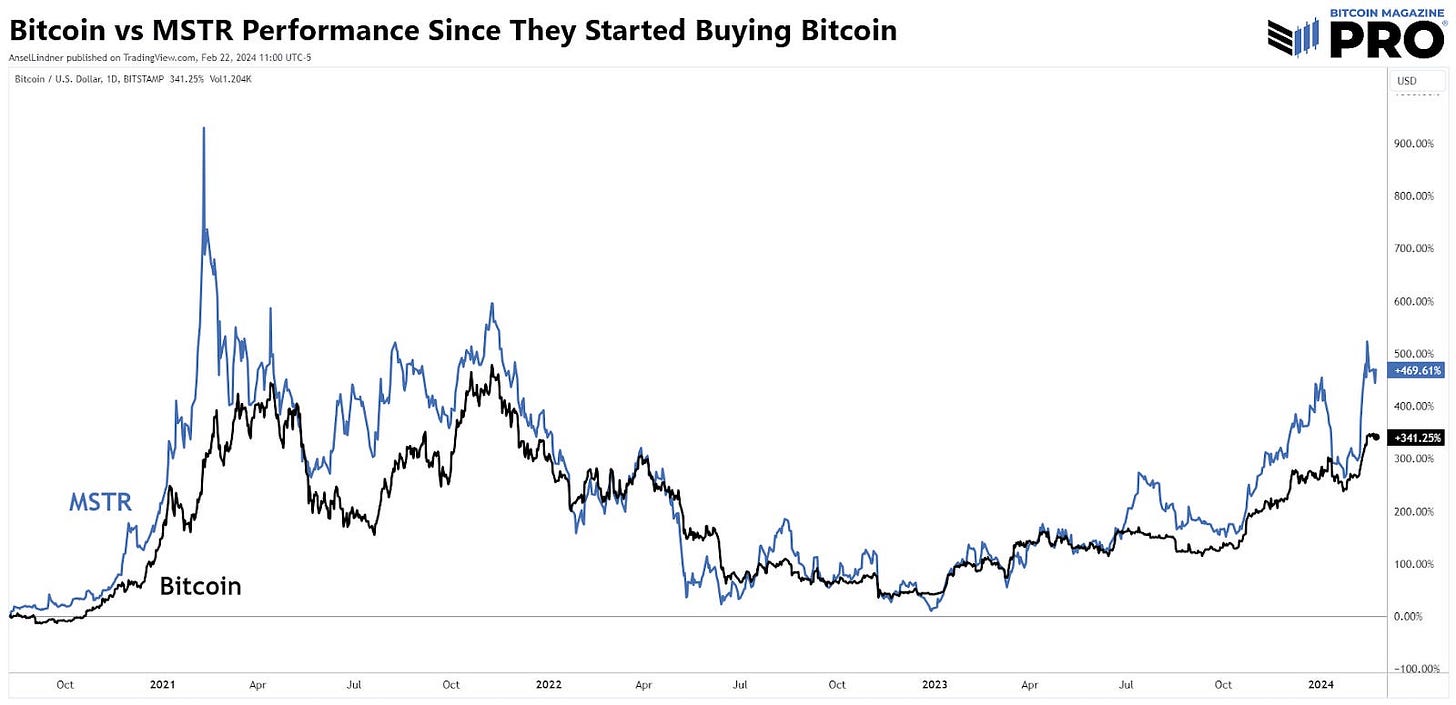

Some see as an example Michael Saylor, the tech exec who largely dropped the idea of focussing on productive enterprise, and simply pivoted to buying up huge amounts of Bitcoin. His company MicroStrategy is now the biggest corporate holder of Bitcoin in the world. It still runs as a software business, but de facto has become a giant Bitcoin ETF, as witnessed by the correlation of its share price with the Bitcoin price.

In fact, Saylor has now become a role model for a whole bunch of copy-cat corporate execs. Rather than investing their profits into new production or employment, we’re seeing hotel chains, healthcare companies, biotech companies, vape manufacturers, and electric car producers direct their funds to buying up tokens. As the Financial Times reports:

In the year to August 5, some 154 public companies have either raised or committed to raise a combined total of $98.4bn in order to buy crypto, according to crypto advisory firm Architect Partners. Before this year, $33.6bn had been raised by just 10 companies…. Even Trump himself is getting in on the action — his family media company raised $2bn in July to buy bitcoin and related assets.”

These new whales will obviously welcome the arrival of more buying pressure into the scene, and that’s currently being helped by the fact that Trump just passed orders to open up the gigantic US 401k pension fund sector to ‘alternative investments’, which includes crypto.

Americans with 401k pensions are normally steered towards lower risk asset classes, but the new measures are designed to bring them into crypto speculation. This mainstreaming is all the rage. For example, J.P. Morgan Chase is now getting into bed with Coinbase, to give Chase customers access to the crypto platform via their bank accounts.

When watching this, you might sense that perhaps all these players know something about the future that you don’t, but the reason they’re leaning in isn’t due to fundamental analysis. It’s not because J.P. Morgan truly believes that Bitcoin will become a global currency or the basis of the financial system. It’s because they’re doing technical ‘trend-following’ on a vast scale, watching the actions of the enormous whale that is the US government, and seeing how deeply embroiled its new ruling dynasty is getting within the crypto markets. They don’t want to miss out when new patronage is handed out. The fact that so many people are predicting this is why Bitcoin hit its highest ever price last week.

The whale in the air

So, let’s say Trump uses the power of the US state to push up the token price by 100%. His average follower, who might have had a couple thousand dollars invested, makes a couple thousand bucks profit. Maybe that helps ease the financial strain on them for a couple months. Michael Saylor, though, makes about $71 billion in that same move.

At that point, people like him may well think about cashing out. After all, what’s the point in holding this object if you’re not ever going to sell to realise your gains?

But, what would begin to happen if he, and other whales, start selling? Well, that’s going to push down on the market, and this is where the lack of fundamentals really starts to get dangerous. In a typical market, the actions of a whale pushing down the price might create good deals, in which case a whole class of fundamental ‘value’ investors and traders come swinging in to act as circuitbreakers.

In a market without these players, though, that drop can very quickly escalate into a precipitous free-fall. After all, the vast majority of people are using a crude model that says ‘I buy Bitcoin because I believe I’ll be able to sell it to others for a higher price later’. A big price drop dents that belief, and - in the absence of ‘fair value’ models that can tell you if the price has gone way below its fundamentals - faith can quickly evaporate…. or else slowly weaken over time as the story gets stale.

Now, here’s a rather amusing irony. One of the big crypto-libertarian lines for supporting the Trump government was that the US government could build up a Crypto Strategic Reserve to hoard tokens that would then appreciate, and enable the government to pay off the US debt.

Let’s think that through. Let’s imagine that the US government builds a huge crypto position. To pay off debt, it would have to go into the markets to begin selling those holdings for dollars, like a colossal whale coming in. But what happens when the biggest whale of them all begins selling into a market that’s full to the brim with not only fickle technical traders, but also precarious pensioners who’ve been encouraged to steer their savings into it?

Well, I’ll tell you. Those traders shit themselves, drop their holdings and run like hell, sending the price plummeting downwards with no emergency brake to stop it. As the US government tries to liberate itself from its national debt, Bitcoin falls by say, 70-90% in a single day. That would be very bad for not only the retail traders and 401k pensioners, but also Michael Saylor, all the corporate treasuries, and the financial sector players. As the market evaporates, the US government is left holding a bunch of deprecated tokens that it cannot sell without crashing the market more.

On the other hand, if the US government isn’t planning to wade into the market, what exactly are all the other whales lining up for? What is their model for the future appreciation? After all, big institutional investors don’t HODL out of some kind of faith or belief in populist finance. They are Harvard-educated neo-liberal elites. No, I think they’re betting on another four-letter acronym. TBTF.

Too big too fail.

I suspect their investment thesis is as follows. They believe that, having hitched itself to the crypto industry, and pushed the market to a new high while exposing vulnerable savers to crypto, the US government will become too enmeshed to retreat. It will be left in a position in which it cannot tolerate a huge crash. Stuck in a state of capture, it will take on a new permanent role in propping up the markets.

Of course, I could be totally wrong. I could be one of those ‘no-coiners’ who is just bitter and jealous. But hey, here I am predicting the ongoing appreciation of the price through government manipulation, so all the coiners should be happy.

Unless of course the manipulation stops.

One the earliest slogans of the Bitcoin community was, ‘don’t trust, verify’. And yet, hoping that the massive whale stays there, suspended out of water, is one helluva leap of blind faith.

The dollar price for the camera will stay fixed at - for example - $600 over the course of days and weeks, while the supposed ‘Bitcoin price’ for it will constantly change, or ‘tremble’, in exact inverse proportion to the shifts in the US dollar price for Bitcoin. This is because the ‘Bitcoin price’ for the camera is actually a countertrade ratio, telling you how much Bitcoin you’d have to sell to get $600

In fact, this narrative is even more circular when we consider that the energy resources required to produce Bitcoin goes up when its price goes up, due to its consensus algorithm that changes the difficulty of the ‘mining’ depending on the demand

thank you for your very clear analysis, that makes sense to me. And then there's the enormous waste of power involved in bitcoin mining. As Mortazavi said in Jacobin (Jan 2022): "If cryptocurrency markets cannot keep luring in enough new money to cover the growing costs of mining, the scheme will become unworkable and financially insolvent."

So much has been written about the "scam" of fiat money and the Federal Reserve. "The Creature from Jekyll Island" and all that. The people who get the newly created fiat money first see their net wealth increase, while those who get it later (the majority) wonder why they keep falling behind.

Bitcoin seems to be especially attractive to younger, entrepreneurial men. To me, it seems to work for them more often than not. But it is volatile. The gaming/gambling aspect of it, I think, gives them a big dopamine hit from time to time when they notch up a spectacular gain. Remembering that rush can stoke fantasies of experiencing that rush again.

The non-level playing field of fiat money and Fed money creation can produce dreams of beating those bastards and their "rigged game" with another "rigged game"?? Am I onto something or just an ignorant old bloke?