Dear readers: this piece builds upon my Lego Model of Corporate Capitalism

Our economies are held together by money, and - most of the time - we hand it over in exchange for goods or labour. Occasionally, however, we hand it over in exchange for future money. For example, if you buy a share on the stock-market, you’re handing over money for a contract promising you a cut of the future profits of a company.

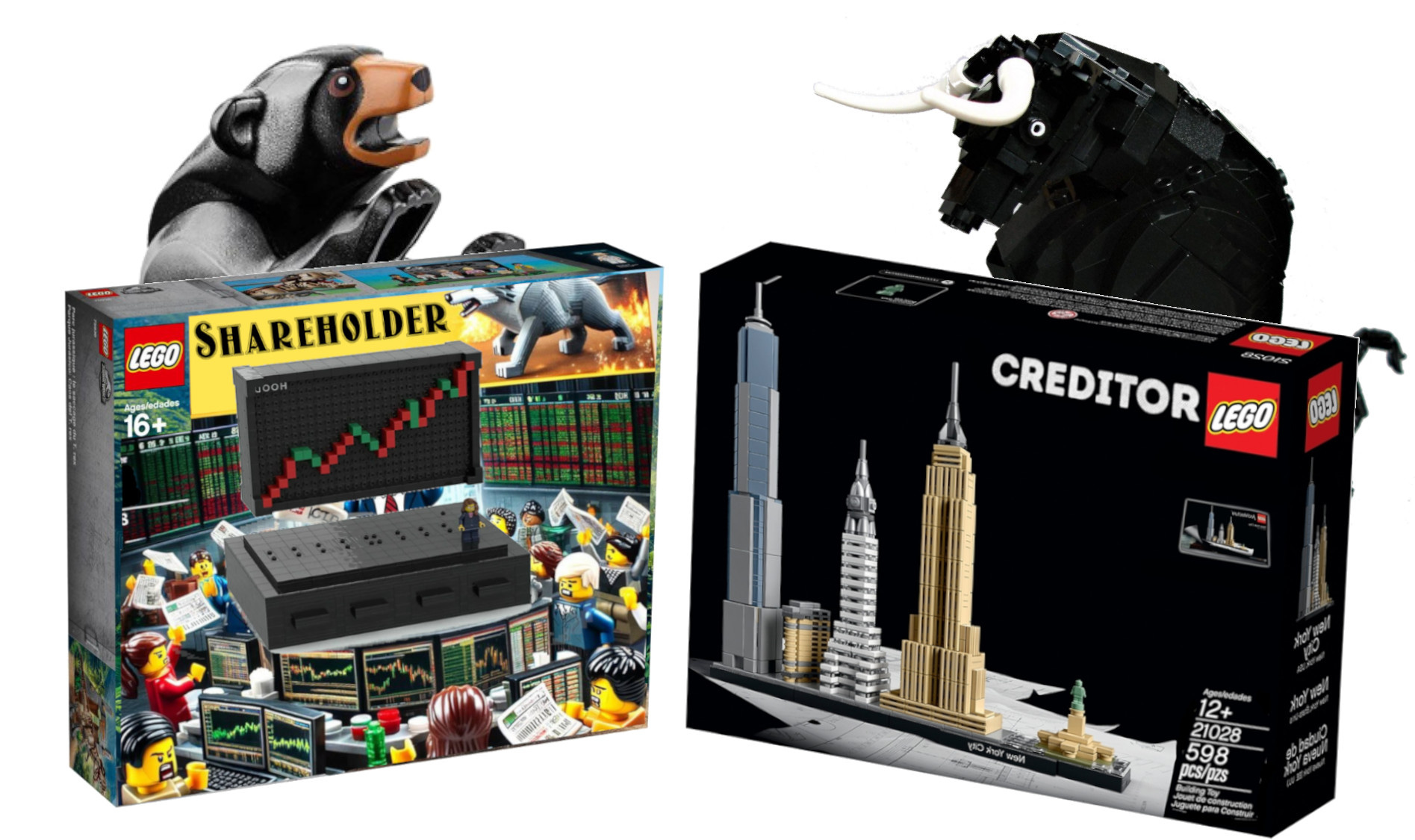

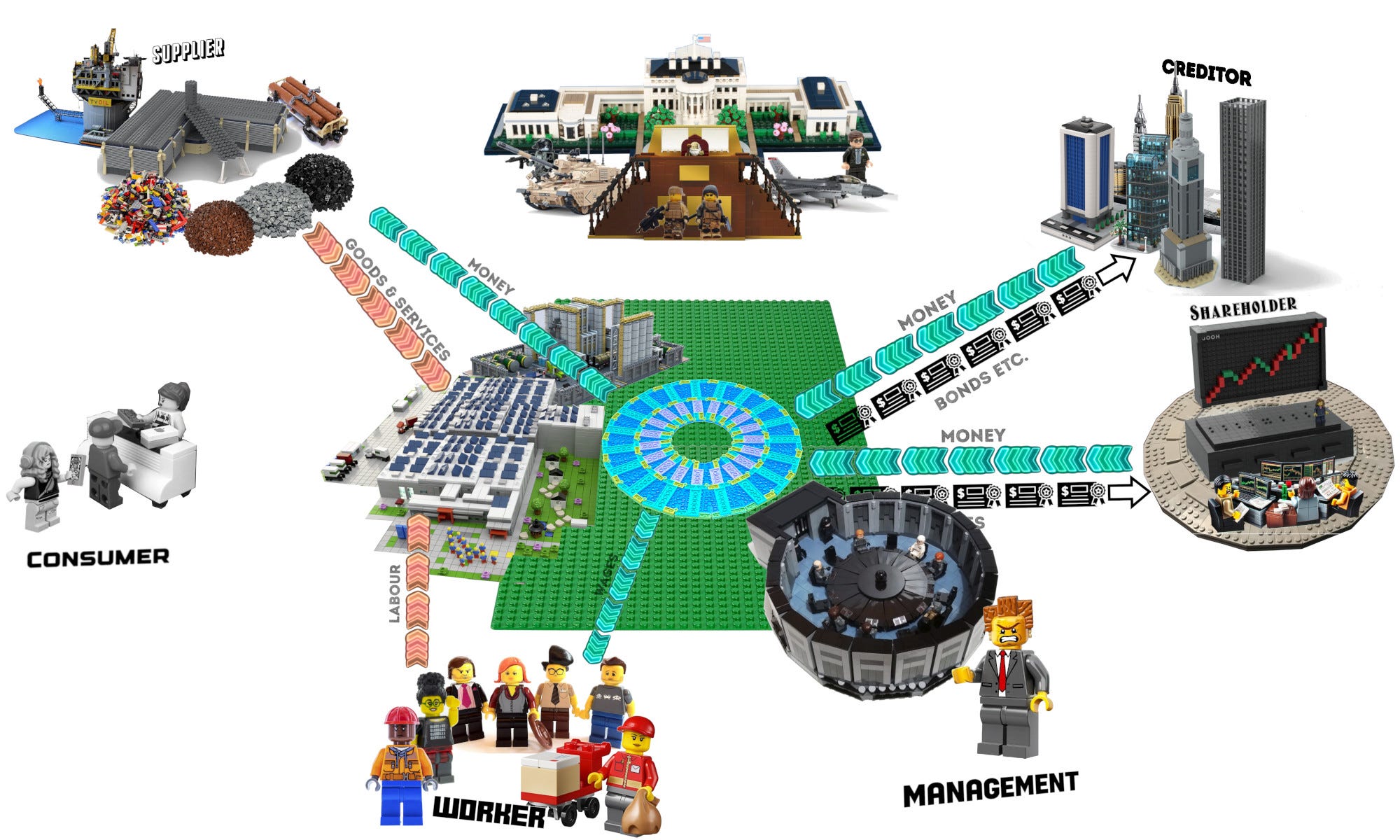

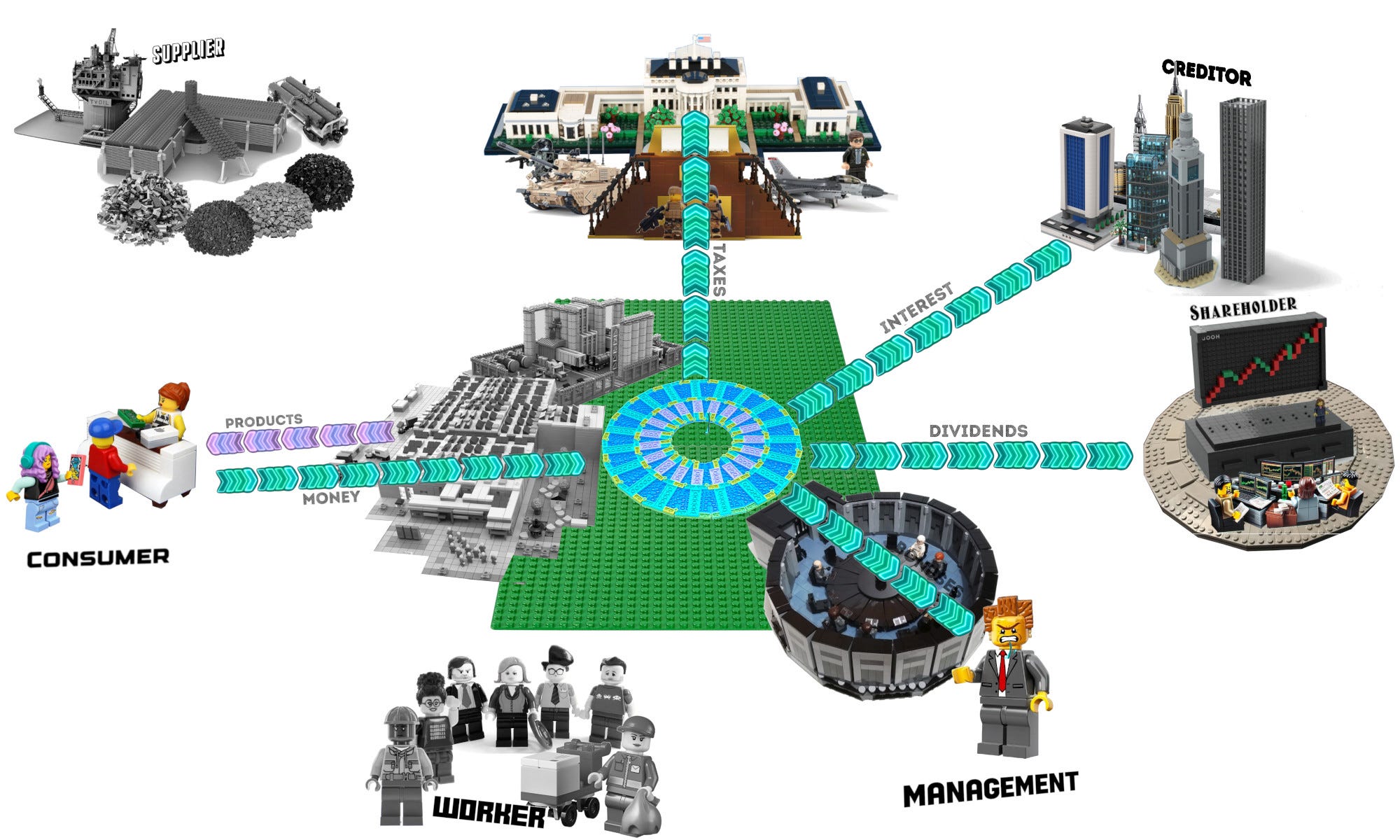

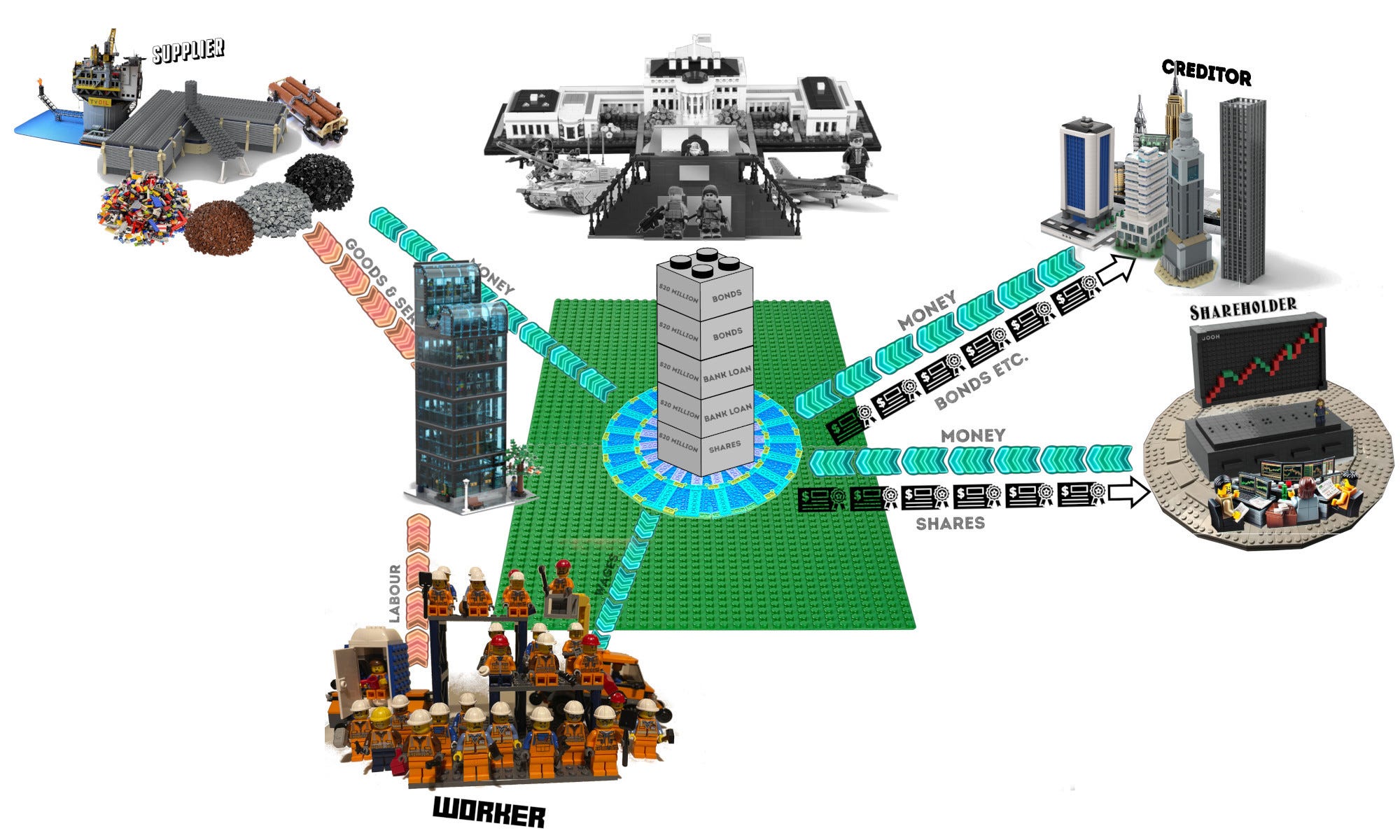

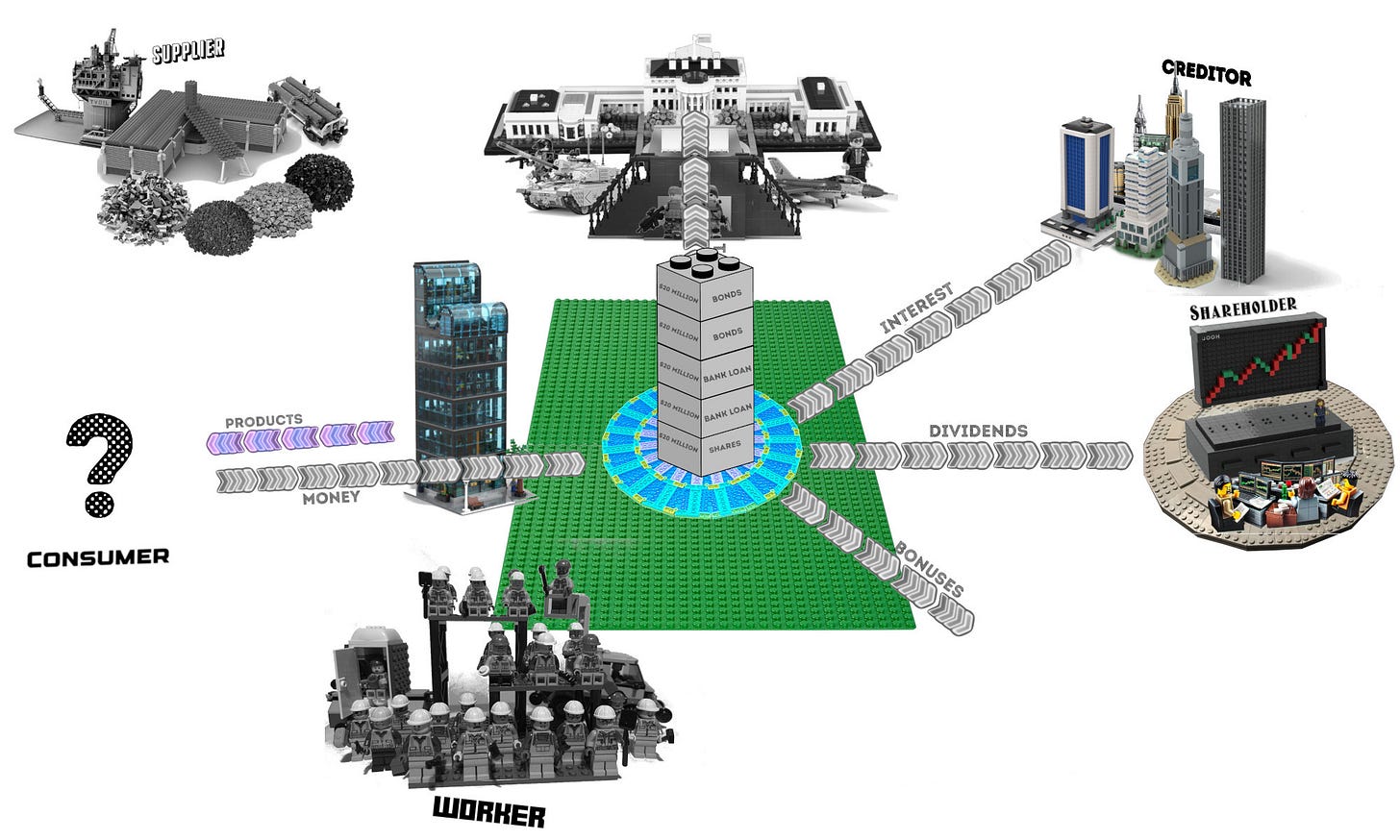

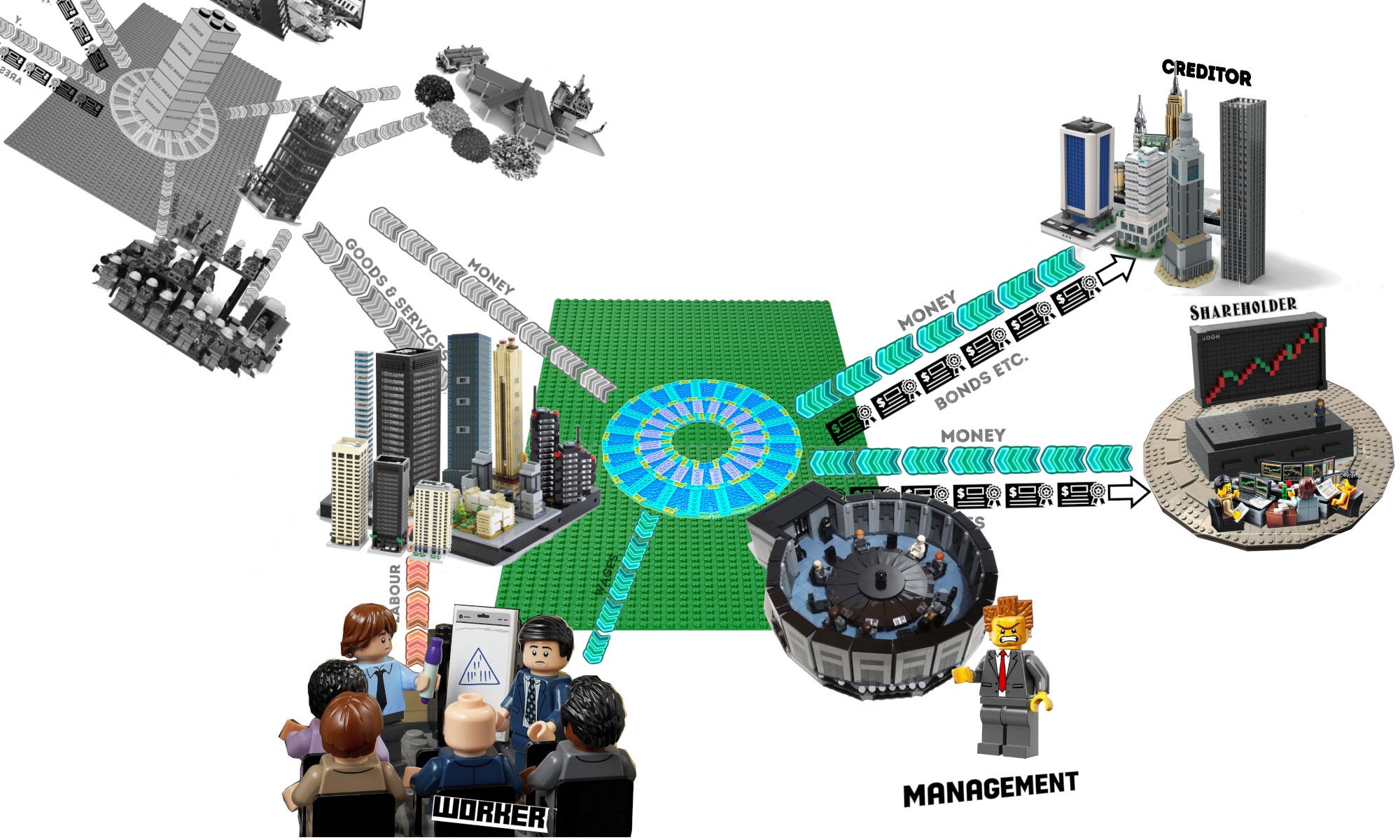

This type of exchange, in which we exchange money for promises-for-future-money, is called financial exchange, and the financial markets are where it happens. Like many markets, the financial markets have a retail side - the smaller players like you and me - and a wholesale side, the mega players like funds, commercial banks and investment banks. The latter players cluster in big cities like London, New York, Singapore and Hong Kong, and in A Lego Model of Corporate Capitalism I showed them taking the lead on capitalizing international corporations. They ‘charge up’ corporate entities with money in exchange for financial contracts like shares and bonds, after which the corporates can blast that out to mobilize workers and suppliers to produce stuff…

That stuff is then is sold to customers, and the revenues are refracted out as bonuses to management, interest to creditors, taxes to governments and dividends to shareholders.

Building a Lego balance sheet

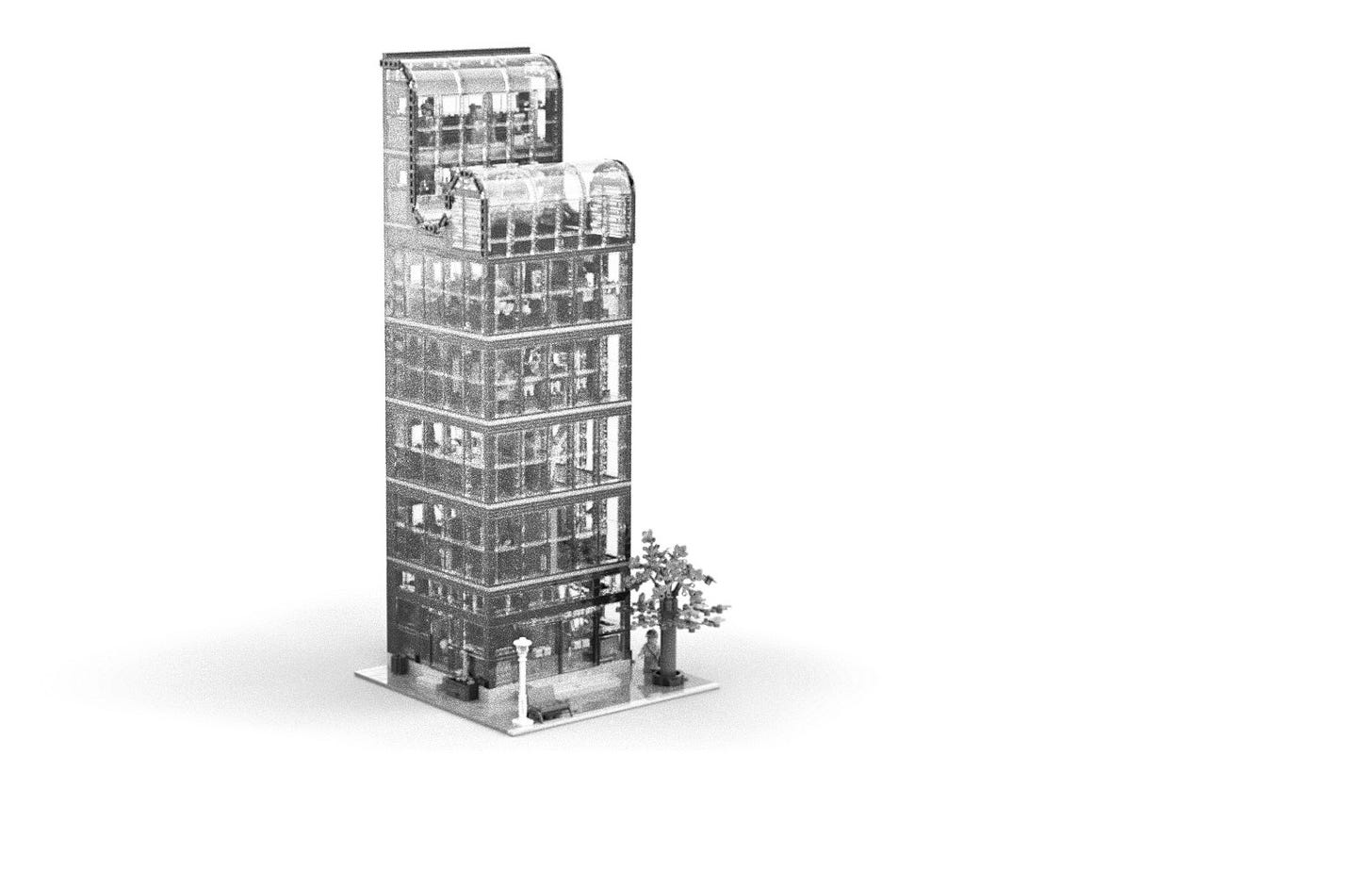

The company shown above is some kind of industrial corporation, but let’s start from scratch in a different sector. Let’s say you’re actually a wealthy property developer who wants to build a luxury office complex for startups in down-town Manhattan. You envision a 6-storey building with open-plan workspaces, a meditation den, a fitness spa, and even sound-proofed booths for therapeutic screaming when the existential emptiness of yuppie life kicks in. Here’s the vision:

Above I said ‘you want to build’, but that’s just a colloquial figure of speech. It’s not like you’re going to turn up with a spade and trowel to lay foundations for this building. No, what you actually want is for a thousand builders with specialist skills, equipment and materials to turn this vision into a reality. You nevertheless want to claim ownership of what they build, so to make sure they have no ownership rights, you need to approach them as suppliers selling goods and services in the open markets. That’s going to cost you about $100 million.

The way to obtain that money is through financial exchange: you need investors to give it to you in exchange for promises-for-future-money. Investment banks are specialists in convincing big investors to do this, but this is a small-ish project and you don’t want a massive investment bank like Goldman Sachs. Instead, you want a small boutique investment bank. You find one called BlueGate Partners. On their website they describe themselves as follows:

That phrase ‘debt and equity capital’ is finance slang for creditors and shareholders who will put in money for different promises-for-future-money. ‘Equity investors’ are shareholders: they put in money in exchange for shares of ownership that will entitle them to a morphing stream of future money (dividends). ‘Debt investors’ are creditors: they put in money in exchange for a promise for an fixed amount of future money (interest and principle). The promise given to equity investors is relative - the returns depend on how well things turn out - while the promise given to creditors is absolute - the amounts remains the same regardless of circumstances. From a legal perspective, absolute promises tend to be senior: they get dealt with first if everything goes to shit (which becomes particularly important in bankruptcy proceedings).

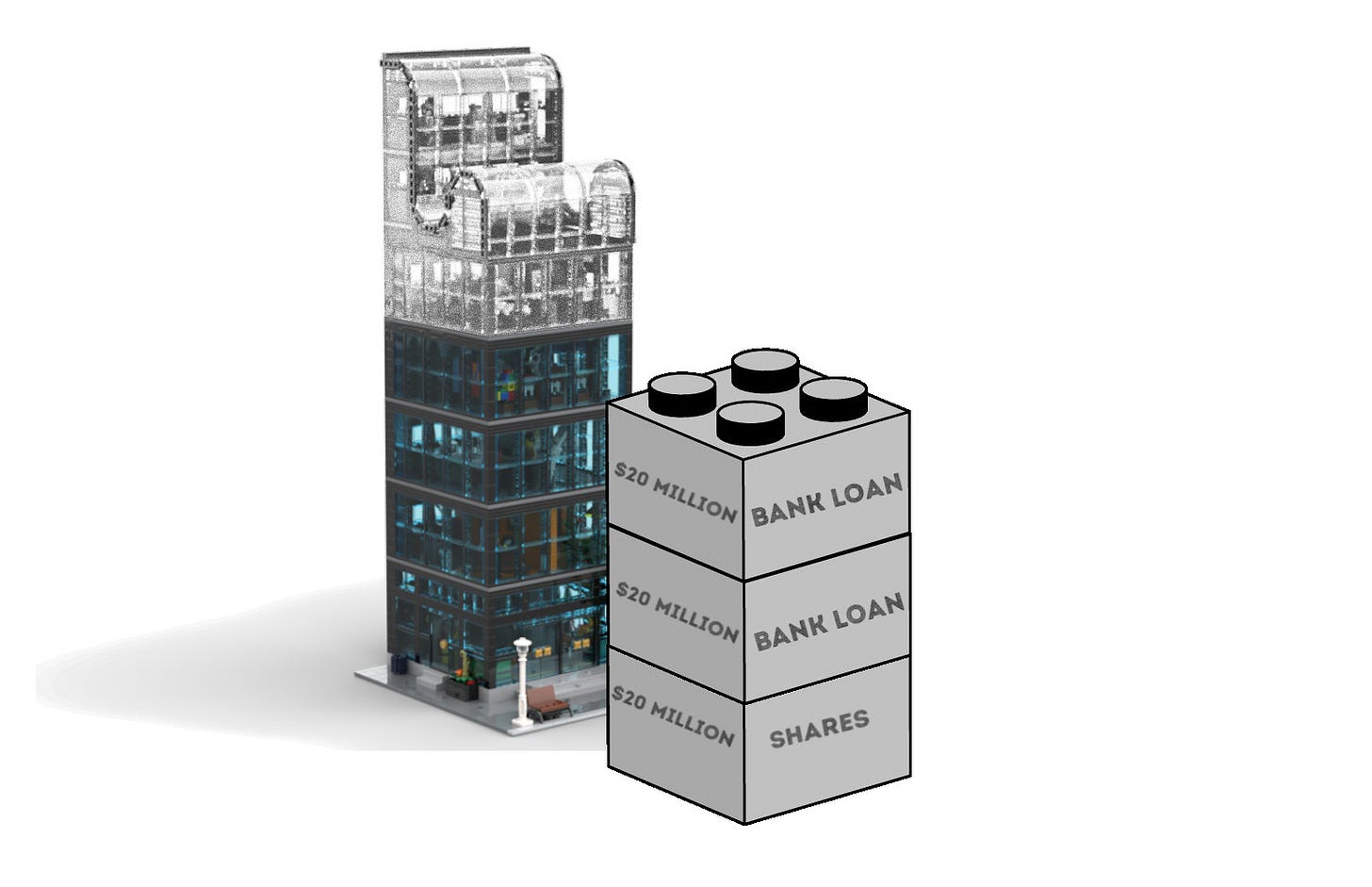

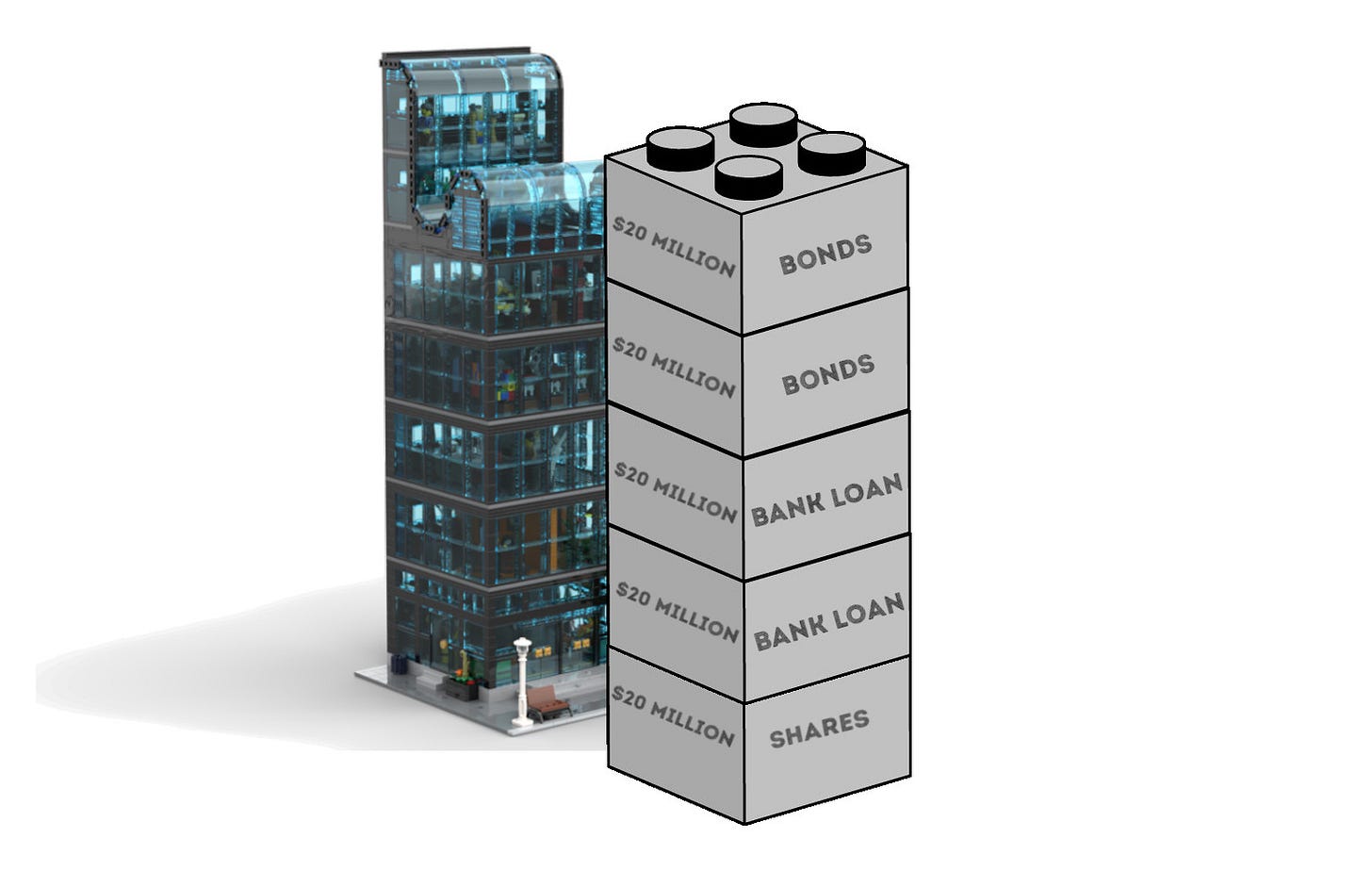

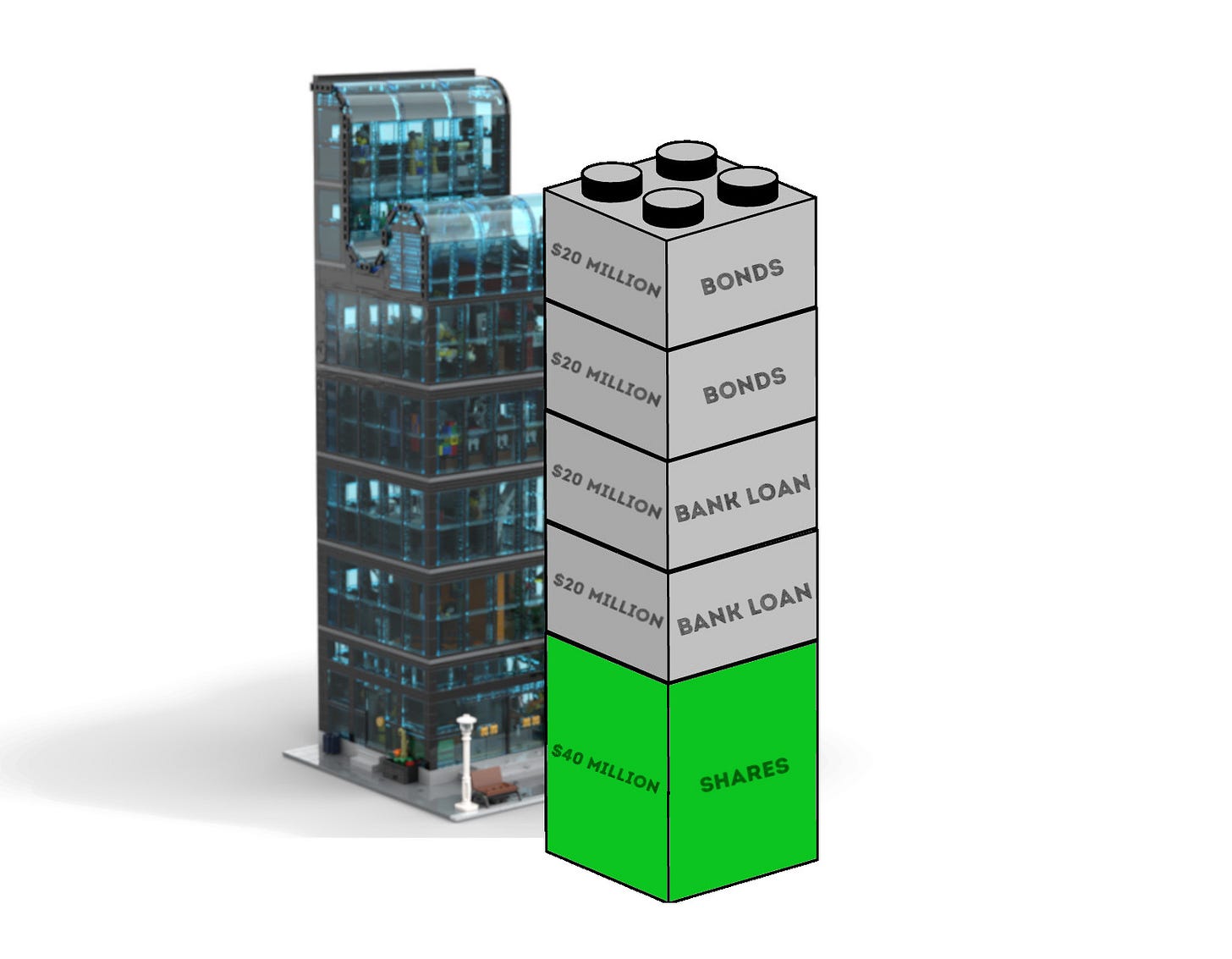

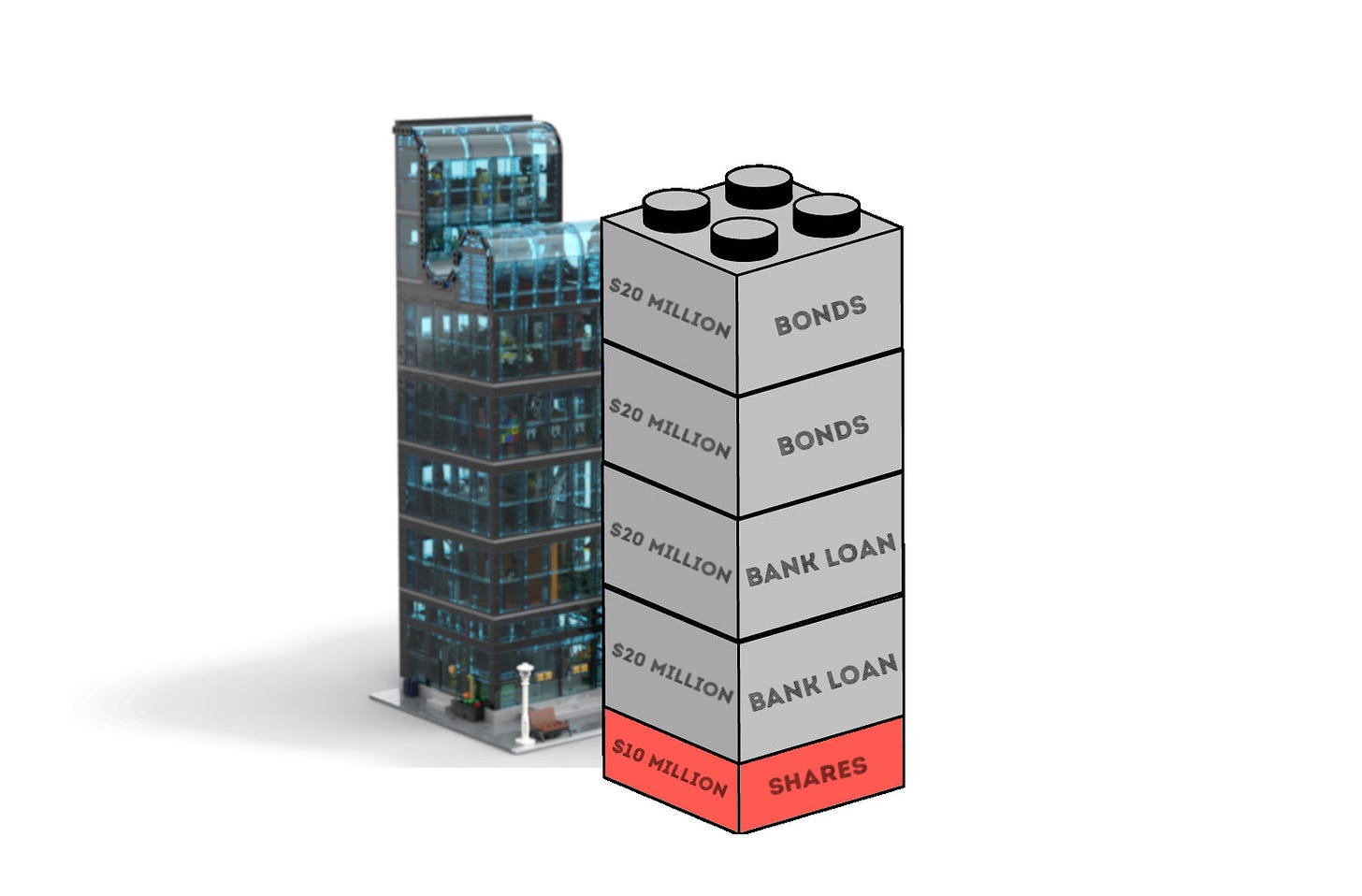

Equity and debt investors will jointly capitalize projects or companies alongside each other. That said, the specific balance of power between them - and between the relative and absolute promises they’ve extracted - can create some interesting properties. One of these is leverage, the phenomenon by which debt investors amplify the returns of equity investors in exchange for protection (equity investors agree to absorb the first losses in a project, but also get to claim amplified gains). Leverage increases as the ratio between debt investors and equity investors increases, so the first thing you and BlueGate will work on is the optimal mix of equity and debt. BlueGate suggests a ratio of 1:4, with 20% equity and 80% debt.

Raising equity

Phase 1 is to deal with the equity chunk, which will be $20 million in total. BlueGate and your laywers set up a new legal entity, which you name Bloks Inc. You’re going to be the lead investor, and will put in $5 million of your own money for 25% of the shares. BlueGate assures you that they are experts in ‘equity placement’, and can find a home for the remaining 75% of the shares. They have many friends at funds who can be convinced to put up the other $15 million.

After a few weeks, and a range of meetings, BlueGate’s team secures pledges for $5 million from a ‘family office’ that runs money for the super-rich, $5 million from an offshore fund, and $5 million from a local property investment fund. The $20 million equity chunk is now ready, but it will only be enough to cover the planning, permits, foundations and ground floor.

Raising debt

So, Phase 2 of the plan is to raise $80 million in debt financing. Again, BlueGate showcases their extensive ties to the super-rich and the super-big:

They want to create a blend of different debt investors (creditors), so their first step is to approach two commercial banks. They get each of them to grant you $20 million in credit (incidentally, this will involve those banks creating new money). This $40 million can probably scrape you another three floors…

There’s still one more normal floor and a fancy roof level to be financed, plus all the trimmings, so BlueGate now approaches a range of specialist funds and high-net-worth individuals to convince them to buy bonds. ‘Buying a bond’ is just the act of lending money in exchange for a fixed-promise-for-future-money encoded into a tradeable contract (‘bond’).

Now that both the equity and debt financing is in place, let’s zoom out and see our Bloks Inc. corporate circuit in action. Imagine the money from the creditors (debt investors) and shareholders (equity investors) charging Bloks up like a battery. That money is then blasted out to mobilize a small army of contractors, suppliers and construction workers who will make the building emerge out of the ground as the money runs down.

As the workers leave, you’re left with part ownership of a completed building, alongside a bunch of other financiers who also want a cut. To realize that cut, however, you need to make a profit, but where’s that going to come from? You need a customer…

You consider trying to manage the property yourself, finding renters who will pay. In this case your customers would be startups buying access to the building. Alternatively, you can just try flip the building by selling the whole thing to some much bigger property holder. You decide to go with this latter strategy, and BlueGate even has a bespoke service to help you find a buyer for the thing they helped finance. They introduce you to a major real estate investment trust (REIT), that has a pre-existing portfolio of buildings that they own and rent out.

From the perspective of this REIT, Blok Inc. appears in their world as a new potential supplier trying to flog them a new asset to add to their existing portfolio. The REIT boss instructs his analyst workers to do an assessment of your building…

The sale

Let’s assume that the REIT decides to buy the building. This is where leverage can get fun. If the rental market is solid, the analysts might suggest a price of $120 million for the building. From the combined perpective of the equity and debt investors in your project, that’s a 20% profit relative to how much the building cost to build. Nevertheless, given that the debt investors’ cut is absolute - it stays fixed - none of that relative increase goes to them. The entire increase accrues to the equity investors, which means - relative to their opening stake - their money just doubled from $20 million to $40 million (with your personal stake going from $5 to $10 million). That’s leverage for you. It’s sometimes called ‘gearing’, because just like a gear might amplify the affect of a foot pressing down on a bicycle pedal, leverage transmits an amplified positive return to the equity stake. Here’s a simplified representation (it’s simplified because the amounts shown don’t account for interest owed to debt investors, but let’s just ignore that):

Unfortunately for you, gearing works both ways. If, for example, the building gets completed just as a global pandemic hits and demand for office space plummets among tech startup workers, the analyst valuation of the building might crash to $90 million. This hits the equity investors first. In this case, a 10% loss relative to building costs crushes the equity by 50%. You get an amplified version of the loss. The debt investors take their absolute share and leave. BlueGate mourns your loss, after which they take their advisory fee - which might significantly eat into that remaining slice you have - and leave.

Calling all lecturers and professors: Next week I have the pleasure of presenting my Lego models to students at Stony Brook University in New York. If you’d like me to talk to your students, drop me a line!

Playing the Advanced Finance Game

What I’ve shown above is pretty basic finance, and there are two things to say about basic finance. Firstly, it’s built upon a much deeper and richer foundational layer of ecological systems, human beings, politics and - eventually - monetary systems, all of which I cover in my Intro to Economic Life course.

Secondly, basic finance can be massively complexified. There are many exciting, and increasingly dodgy, things you can do to play a more advanced finance game, such as:

Offshore finance: build complex legal structures, like a shell company that owns a shell company that lends to a shell company that is also owned by you, so that it can buy the shares

Financial engineering: create new and weird combos and hybrids of debt and equity (e.g. Silicon Valley thrives on ‘convertible notes’, debt instruments with inbuilt options that can convert them to equity)

Finance your financing: In our original scenario above, you were required to put in $5 million, but you could borrow $4.5 million of that from another bank (or other debt investors), which means you could put in $500k to get a 25% equity stake, which means you’re now leveraging your leverage! (something that hedge funds are notorious for doing)

Securitization: the original banks involved might take their stakes and place them in a new offshore vehicle, alongside 1000 other loan contracts they’ve harvested, after which they can ‘tranche’ that package into different equity and debt slices that can be sold off. Now the combined interest that accrues to the pool of loan contracts can get refracted out like a monetary rainbow to a whole range of new investors, some of whom might insanely leveraged

Derivatives: you might make bets on the side to protect yourself against changes in the average price of properties (e.g. property index derivatives), while the banks might be using interest rate derivatives to manage various aspects of their exposure. Perhaps your bond-holders might pay away some of their interest into a credit default swap (CDS) offered by an investment bank, in exchange for compensation in the event of your bankruptcy

Mix it all up! Perhaps that investment bank can take the other side of that credit default swap, and place it - alongside other CDS contracts - into a new offshore vehicle. Now they can sell the tranches of that new SYNTHETIC CDO! This is highly recommended if you wish to trigger a global financial crisis.

This is why I rely on Substack for ALL my education.

Thanks!…but why just ignore interest owed to debt investors?