The Deposit Myth

How a linguistic glitch confuses the hell out of economists and the public alike

Paying subscribers can access the audio version here

Imagine the fiery origins of the earth, with asteroids crashing and depositing debris all over the planet, and volcanos depositing lava. Nowadays this leads us to discover cobalt deposits, gold deposits and iron ore deposits in the earth’s crust.

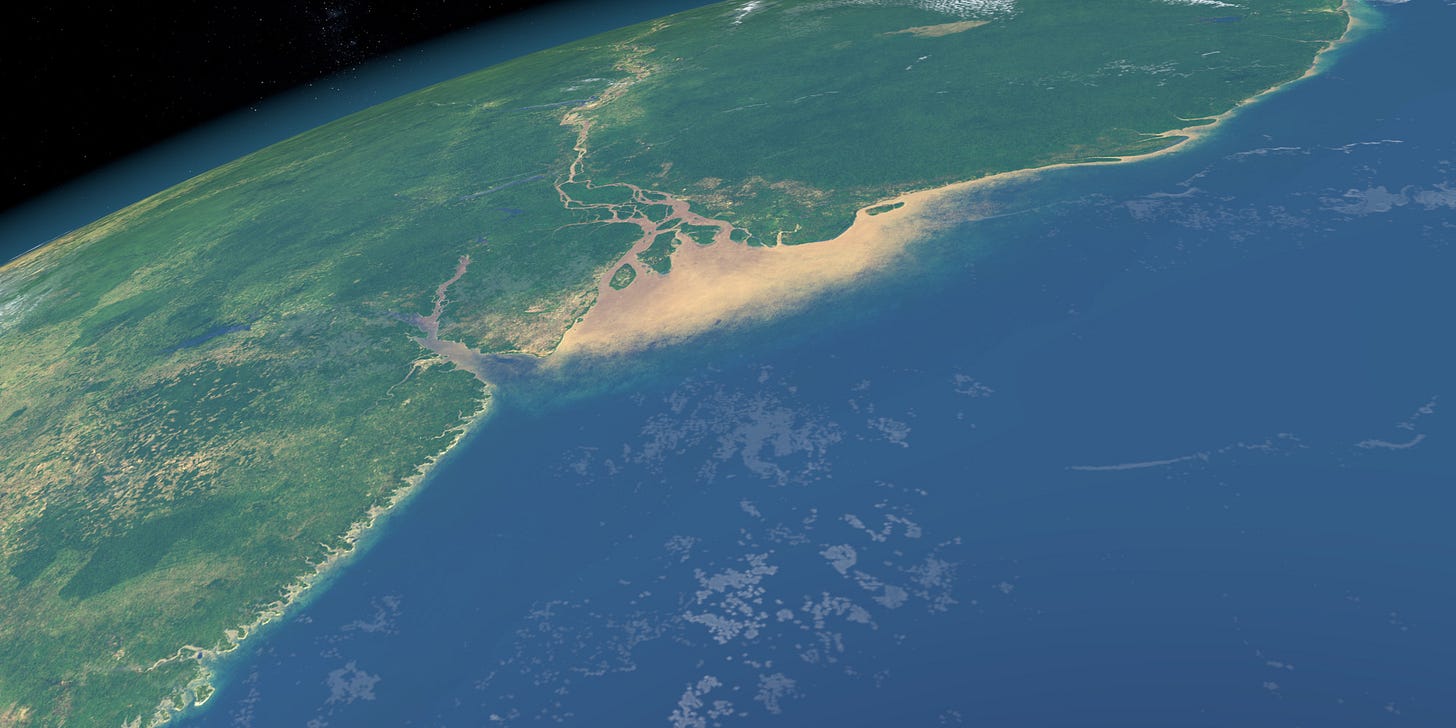

Now picture the Amazon river raging in flood, and bursting out into the Atlantic ocean where it deposits a payload of sand. We might say there’s now a sand deposit that’s been deposited into the ocean.

I can list countless more examples of' ‘depositing’. For example, picture me pouring beer from a jug into a cup. I'm depositing beer to create a 'beer deposit' in the cup.

The basic rule in the English language is that the verb ‘deposit’ creates a noun of the same name: the volcano 'deposits granite deposits', and the river 'deposits sand deposits', and so on. Following this linguistic convention then, surely we’d be correct in thinking that we 'deposit a bank deposit'? Surely, much like the beer I’ve poured into a glass, the bank deposit is money I’ve poured into the bank.

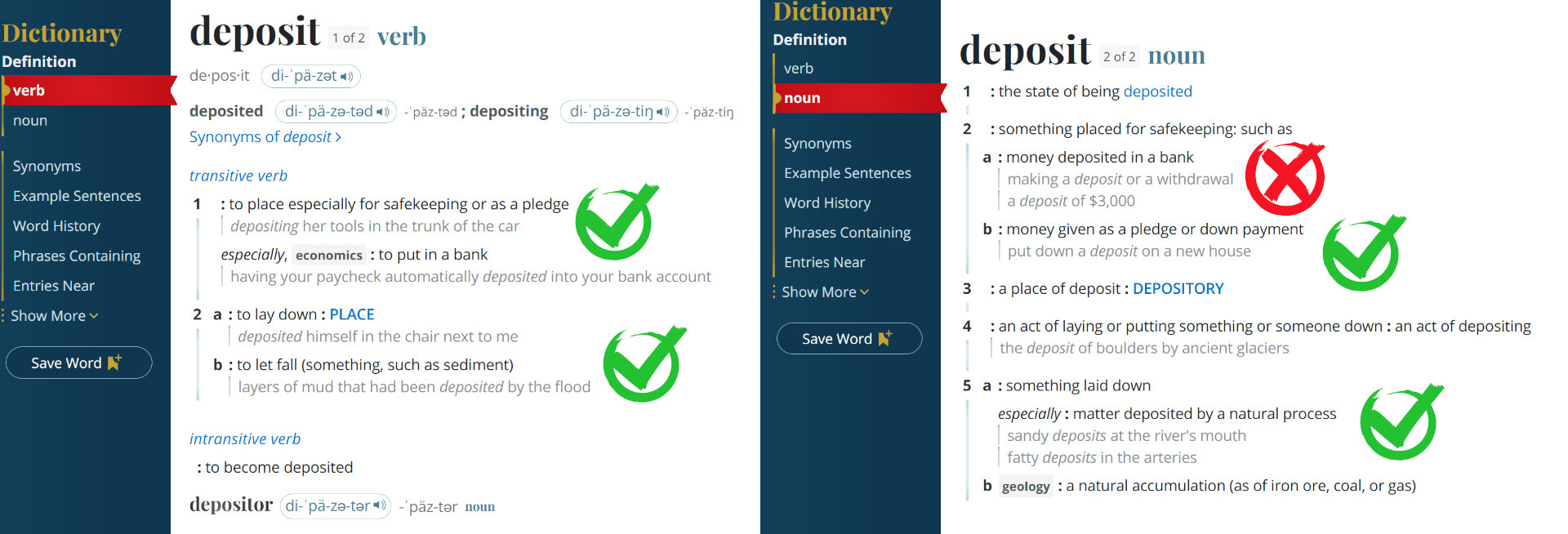

It certainly seems that way, and reputable sources like the Oxford Dictionary of Finance and Banking confirm this when they tell us that a deposit is “A sum of money left with a bank, for safekeeping or to earn interest”. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary corroborates this, stating that the noun version of deposit is 'money deposited in a bank'.

Unfortunately, they’re all totally wrong, and this error wreaks havoc on our undestanding of Big Finance.

Unhitch the linguistic glitch

To understand the problem, let’s go through a thought experiment. Imagine you go to a casino on a cold night, wearing a big coat. Before entering the main area, you stop by the cloakroom and deposit your coat there. In return, the clerk issues you with a little numbered slip, which enables you to claim the coat back.

There’s a nuance to be aware of here. The casino cloakroom has just become a custodian of your coat, but they do not own your coat. You retain ownership, and the slip is your proof of ownership. If you lose the slip during the night, you still own your coat, but will have to find some new method to prove that (perhaps you’ll have to describe its features, or tell the clerk what’s inside its pocket, to prove ownership). For now, though, you stuff the slip into your wallet.

Having done this, you go through to the cashier area, and hand over $250 in cash to get $250 in chips. In a sense, you’ve just ‘deposited’ cash to get the chips.

This situation is similar to the cloakroom - you deposit one thing and get another - but it’s also slightly different because in this case you no longer own that cash. Let’s look at this through an ‘asset vs. liability’ lens. Assets are things owned. Liabilities are things owed. For the casino, the cash you hand over becomes an asset to them, which means you’ve lost that asset, but they simultaneously have to issue chips out to you, which becomes your new asset. You replaced one asset with another.

To the casino, however, those chips are liabilities, because they give you, the bearer, the right to demand cash back from the casino at the end of the night. This is confirmed in the highlighted section below from the UNLV Gaming Law Journal (Volume 5, Issue 1, 2014).

A chip isn’t a proof of ownership of some specific thing, like your cloakroom slip is, but is rather an ‘IOU’ issued out by the casino that gives you a claim over them. When presented back, it will force the casino to hand over some of its assets to you.

So, hypothetically, if you were to get totally drunk during the evening, and accidentally drop some chips into the toilet and then unknowingly flush them down, the liabilities of the casino will decrease while their assets stay the same. If you stumble up to the counter, having lost these chips, and try to ‘prove’ that you actually own cash behind the counter and want it back, they’ll reject you. The only way you’re getting cash is to present the chips to them.

Where does the noun reside?

In both cases above, you ‘deposited’ (verb), so where do the subsequent noun-versions of ‘deposit’ reside? Well, there’s a bunch of coats being held in trust in the cloakroom, so that’s a ‘coat deposit’, and there’s a cash pile behind the cashier’s desk, so I guess we could call that a ‘cash deposit’. As you walk around the casino, however, you’re not holding those nouns. You’re holding the things issued out - a slip and chips.

Let’s create an odd scenario. Imagine if you started calling the slip a ‘coat deposit’, saying ‘I have a coat deposit in my wallet’. It sort of sounds like you’ve stuffed a big coat into your wallet, but if someone heard you say this, they’d guess the context and say ‘oh, you have a coat deposit receipt in your wallet’.

Now, imagine you start calling the chips ‘cash deposits’. You turn up at a poker table and say ‘how many cash deposits to buy in?’ The dealer is going to look at you strangely, and say ‘you mean how many chips to buy in?’ At best you’d be thought of as a little eccentric for using this language, and at worst they’d think you’re an idiot. You’re holding chips, not cash deposits.

This, though, is exactly what I think about when I hear economists talking about ‘bank deposits’. Economists, like our confused punter above, use the term ‘deposits’ to refer to the chips issued out by banks, but in doing so erroneously give off the impression that they’re talking about ‘cash behind the counter’. They use a term that denotes ‘thing put in’ to refer to something that’s actualy issued out, and this seriously compromises our understanding. So, when thinking about 'bank deposits' you need to unhitch your mind from the traditional verb-noun pairing.

Why the word ‘bank deposits’ is a liability to society

The best way to understand banks is to compare them to our casinos, because so-called ‘bank deposits’ are closely related to casino chips. When you deposit (verb) cash into a bank, it goes into their assets. Think of it as entering the ‘treasure chest’ of things they own. Like our casino, they simultaneously issue us IOUs, or ‘digital casino chips’. That’s what you see rendered on the screen of your phone or computer when you’re looking at your bank account. In other words, your bank account is not a place where the bank is ‘storing’ money you ‘put in’. It’s the place where a bank records how many chips it has handed out to you.

Bizarrely, however, these chips get called ‘deposits’. You can see this if you look at a bank balance sheet. Their treasure chest is described on the asset side, while claims against that are described on the liability side. Here’s the balance sheet of Barclays Bank, for example. Notice that ‘deposits’ is on the liability side, because they are issued out, not put in.

If deposits were truly ‘in’ the bank, they would be in the assets section on top. So, while it’s true that we can ‘deposit’ money into Barclays, the money we deposit there ends up getting called ‘cash and balances at the central bank’, while the thing they call ‘deposits’ refers to something emanating out of the bank. This is definitely a poor choice in terms, but I’m going to assume that a senior banker at Barclays basically understands that a ‘bank deposit is not deposited’. When it comes to economists, however, I’m not so confident. In their case, they often authentically seem to think that the deposit refers to a ‘thing put into bank’.

For example, when economists are describing what they call ‘fractional reserve banking’, they’ll say something like this: ‘people deposit money into banks, but banks then lend that out to borrowers while telling their depositors that it’s still there’. Here for example, is the major finance site Investopedia saying this exact thing:

When you consider the Barclays balance sheet, and the fact that ‘deposits’ turns up on the liability side, you’ll start to see how idiotic this description is. How does Barclays ‘loan out’ something that’s a liability to them? That’s like saying ‘I loaned my friend my outstanding tax bill’.

Let me explain the mistake they’re making. They’re starting from the erroneous assumption - derived from that verb-noun convention - that a deposit is a ‘thing inside the bank’, rather than a ‘thing issued out by the bank’. They then imagine the bank taking that and handing it out to people, but by doing this they’re falling into the classic OTOMI problem - the One Type of Money Illusion that I describe in my piece The Casino-Chip Society. They’re failing to realise that the term ‘money’ refers to more than one thing, and comes in different forms with different issuers.

In particular, the term ‘money’ simultaneously refers to state-issued cash and bank-issued digital casino chips. So, take that phrase ‘banks lend us money when we ask for loans’, and replace ‘lend’ with ‘issue’, and ‘money’ with ‘digital casino chips’. Here’s what it looks like: banks issue us new digital casino chips when we ask for loans.

This is a much more accurate description of bank operations. If you look at the balance sheet above, you’ll notice that the digital casino chips (‘deposits’) on the liabilities side far exceed the 'cash and balances at central bank' category in the assets section. It’s not that Barclays is sneaking cash out of its ‘treasure chest’ and trying to hand it out to borrowers. It’s that Barclays is simply issuing new digital casino chips at will, against the backdrop of its treasure chest, to people who ask for loans. Banks aren’t limited1 in the amount of chips they can issue out (albeit it puts them at risk to issue too many, which is something that regulators try to limit through the various requirements of the Basel III accords), and given that these chips get called ‘deposits’, it follows that they can expand their deposits even if nothing was deposited.

This is the actual operation of modern ‘fractional reserve banking’, or - more accurately - credit creation of money. The key thing is that banks issue new digital chips in order the harvest loan assets, which is what you see filling up the other sections of the asset side of their balance sheet. If you want to delve deeper into that, see my Emotional Guide to ‘Fractional Reserve’ Banking.

Update the dictionary

I wish we could just stop using the noun ‘bank deposit’, but unfortunately it’s encoded into our language, textbooks and politics like a dinosaur etched into the fossil record. If only there was a global ‘update the dictionary’ council that I could appeal to, but in the absence of that I’d at least like to have a chance to show you how I’d rewrite the Merriam-Webster definition. This is how I’d do it.

The verb-noun glitch creates all manner of weird anomalies when you start to play with it. For example, if I do indeed insist on depositing a bank deposit it will in fact destroy it, because - using our updated definition - that would actually mean 'handing chips back to the bank that issued them'. Incidentally, this is actually what happens when you repay a loan. You’re literally retiring bank chips from circulation.

If you have any further suggestions for how to dislodge this term, or what terms you’d use in it’s place, I’d love to know.

When I say they ‘aren’t limited’, I mean there’s no natural scarcity to the chips, in the same way as there’s no natural scarcity to, say, the amount of promises you can utter. But, much like your reserves of energy can get overrun if you promise too much to too many people, banks reserves of cash can get overrun if they issue too many chips. This is what I describe in An Emotional Guide to ‘Fractional Reserve Banking’

I’m not sure this is right, but what I’m getting from this is that money has a psycho-mathematical ontology. It is subject to nomothetic mathematical operators, but it is also fundamentally “of the mind”, and this renders it hard to think about except in terms of analogy and metaphor. The challenge is finding the metaphors that provide a coherent image when applied to the various facets or types of money.

Brett, I've recently written on The Deficit Myth and The Surplus Myth, which looks at how money is created, allocated and destroyed.. and who benefits, and the impacts on the economy, looked at in accounting terms across the Profit and Loss and Balance Sheet of both the Government and the Private Sector

https://medium.com/@michael-haines/modern-monetary-theory-is-not-a-theory-its-how-the-system-works-b0c0fe59b6d6