Detachment Theory

Libertarianism in the anxious-avoidant economy

Paying subscribers can listen to me reading this piece here

Attachment Theory starts with a simple premise. We’re hardwired to need others.

At one level this is obvious. No person has ever survived without getting birthed and raised by others, so there’s no primordial ‘self-reliant individual’. Even ‘feral’ children, who are abandoned or neglected, seek attachment with other creatures.

Attachment theory, though, focuses on how this reality has imprinted into us emotionally over millennia. Our brains are set up to seek out and attach to others like a magnet.

The fact that we seek attachment to feel whole shouldn’t be confused with a hippie mantra like ‘we are all one’. Attachment theory recognises that social magnetism is complex, and that not everyone deals with it in the same way. People with a secure attachment style find it easy to dock into others to make stable connections, while those with an anxious style often try to connect too hard, like an overbearing ‘clingy’ magnet. Those with avoidant styles behave like a magnet repelled, keeping distance, while in the background longing to find some stable connection in the field. Then there’s the anxious-avoidant style, which fluctuates between those latter two.

The research field comes out of early childhood psychology studies, and it’s obviously more nuanced and varied than the pop version I’m sketching out above. That said, its core idea - that attachment is the norm and that we have different strategies to achieve it - has an implicit politics to it. That’s because it goes against decades of neoliberalism that told us detachment is the norm.

In the neoliberal worldview, reality begins and ends with solo ‘sovereign individuals’, rulers of themselves who are imagined as whole without others. In this view, collections of people are just a secondary phenomenon: social arrangements are incidental structures voluntarily built by detached individuals through acts of choice, and they could just as easily be dismantled. This is why Margaret Thatcher (in)famously said ‘There is no such thing as society: there are individual men and women, and there are families’ (she had to add families in there, because otherwise she’d be left with a vast collection of feral children).

This belief in the logical priority of the solo individual pre-dates the Thatcher era. It’s been standard in the economics discipline since at least the 19th century. Open any Econ 101 textbook, and you’ll be told that markets - which are collectives of people - are formed by solo agents (or units) that choose to interact with others for individual gain. The background message is obvious: detachment is the starting point, and forming attachments is a personal choice that comes after.

While many branches of economics describe the world as if it is made up of solo individuals, political ideologies like conservative libertarianism prescribe that it should be like that. There are obviously nuances to this: settlers on a colonial frontier, for example, might take on a communitarian-tinged libertarianism, where they maintain tight local solidarity while telling the distant state to get lost. In general, though, the conservative libertarian worldview imagines the individual as the primary reality, and then asserts that any attempt to expect, or impose, societal obligations and attachments is both unnatural and oppressive.

Thatcher blended these descriptive and prescriptive strands together when she said ‘economics are the method; the object is to change the heart and soul’. The neoliberal movement she spearheaded aimed to break down collectives like unions, which had been encouraging working people to think of themselves as part of a whole with rights. The changing of their ‘heart and soul’ involved getting them to see themselves as atomized individuals who wouldn’t stand in the way of the natural forces of ‘free markets’, which - if left to run - were supposed to revitalize the world and bring spontaneous order and progress.

This Thatcherite vibe is found in many of those popular ‘how to be successful’ business books you might find in an airport bookstore. The cultural message lingering in the background to those is: society owes you nothing (because it doesn’t exist), and life’s unfair, so don’t appeal to authorities, and don’t join a union. Stop wasting time thinking about where the waves of insecurity come from and just learn to surf them. Just start your own business and outcompete others. Learn how to speculate on property. Learn how to beat the market. It’s a dog-eats-dog world, so eat or be eaten.

This ethos also bleeds into the broader self-help book genre. Self-help authors don’t necessarily perceive themselves as politically libertarian, but the genre is set up to downplay systemic forces that affect your life, and to speak to you as if you really are the primary agent of change. In other words, you can’t change the world but you can change yourself, so stop whining and take control. You’re the only one who can solve your problems.

I have a long and complex history with libertarianism, because - socially and emotionally - I’ve often come close to its ideal. I’m what you might call a lone wolf, someone historically wary of social ties. I’ve had a tendency to try to keep them loose and breakable so that I can easily ‘exit’ any group scenario. When I was younger, I’d never look for mentors, and would seldom ask for help. I wouldn’t ask for state welfare, despite often being highly precarious, because I didn’t perceive myself as entitled to it. In many respects I’ve often been an ideal example of the ‘self-reliant’ atom that Thatcher wanted.

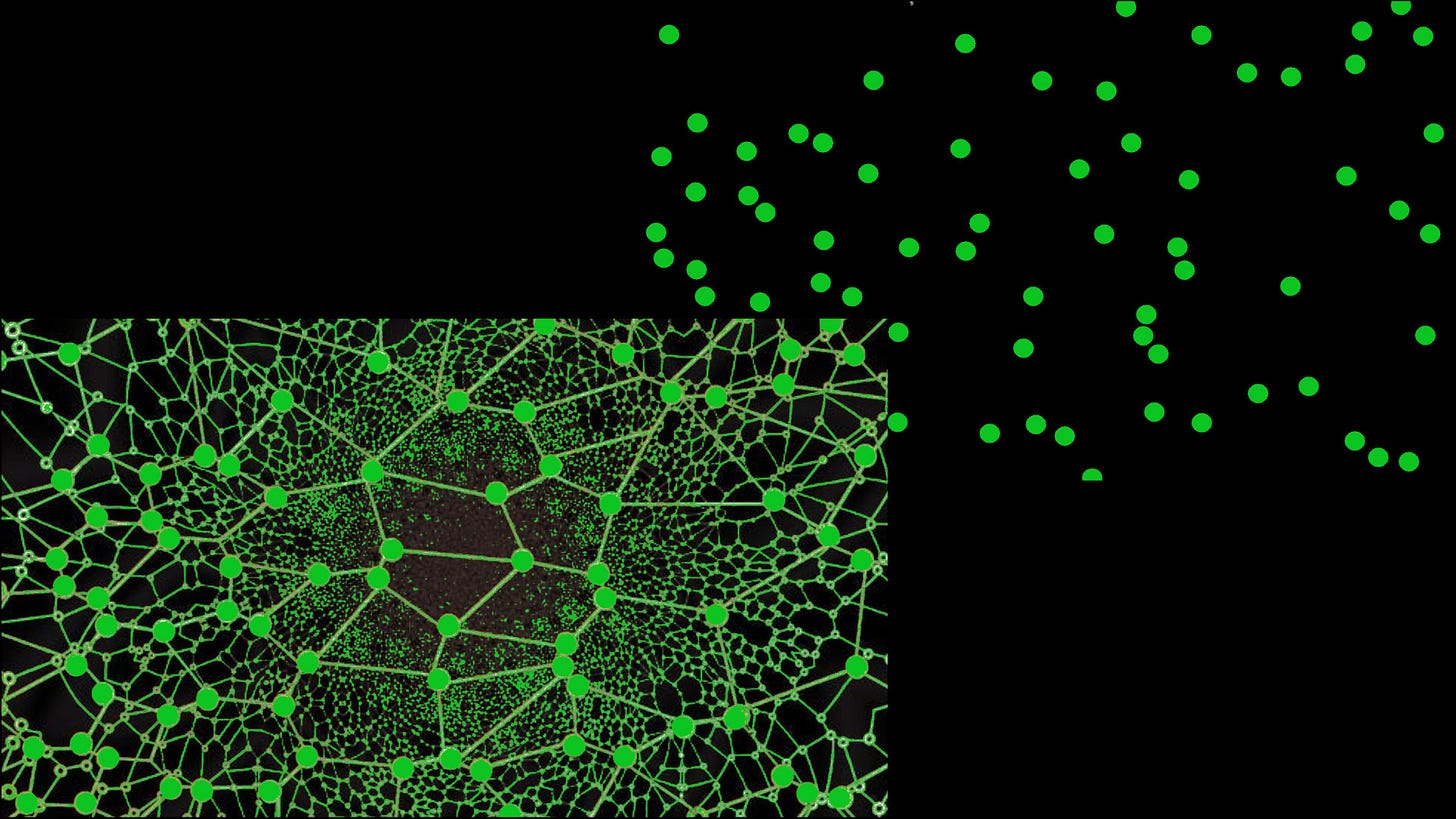

The main difference, though, is that I also have a heavy streak of left-wing anarchism in me, and one fundamental disagreement people like me have with right-wing libertarianism concerns starting points. Libertarian-minded economists won’t deny that humans form relationships and that we end up entangled, but they imagine that the starting point that preceded this is a collection of detached individuals who step forward to create the relationships out of choice. Behind any network they see a group of individual nodes that chose to build it. The nodes precede the network, as it were.

In their worldview, detachment is (or should be) the primary state, and attachment the secondary, but this polarity is wrong. Nodes don’t precede and build networks. Networks precede and build nodes. This is why I gravitate towards the insights of Attachment Theory, which posits that attachment is the primal state, and that forms of ‘individualism’ - like my avoidant lone wolf tendencies - come later.

Attachment Theory now finds itself on the self-help book shelves. There’s an irony to that, though, because the field tells us that embedded in every self is an inherent pull towards other selves, so true ‘self-help’ is an inherently collective activity.

Economic Attachment Styles

Attachment theory started by looking at kids’ relationships to their parents or primary care-givers. The theory was then extended to romantic relationships, friendships, and even to more formal associates like work colleagues. It can, however, also be extended even further to our most diffuse relationships, like those we have with the strangers that surround us, those people who we call ‘the public’ or ‘the economy’.

‘No man is an island’ is certainly true at an interpersonal level, but nowadays it’s even more true at a global economic level. How much stuff that your life depends on is created by you? Almost nothing.

For example, the raw materials and components in the screen you’re reading this on were extracted and assembled by thousands of people, and the raw materials and components in the tools they used while doing that were extracted by countless more. Those countless more, in turn, drew upon countless more in their endeavors, and so on.

Furthermore, who produced the workers who produced the stuff that produced the screen? The actual full supply chain of the screen will extend back decades to include every parent who raised the workers, and every person who contributed to their baby food. In fact, if you really traced the entire chain, it would eventually encompass a big chunk of the planetary population, because how can you tell where it begins or ends?

You know almost none of these people who form this colossal multi-generational meta-supply chain, but the fact that you look at this screen is evidence of the fact that you’ve found some way to attach to their labour.

This is called interdependence, and it’s the fundamental reality of any economy since the beginning of human history. Libertarian-minded economists don’t necessarily reject this, but they always imagine that interdependence is a secondary phenomenon preceded by independence. For example, the neoliberal darling Milton Friedman is famous for his homage to a pencil, a simple object created through massive intersecting global supply chains.

In the video above, he marvels at the wondrous intelligence of human self-organization in these supply chains, but like all conservative economists he imagines that the workers are like thousands of detached nodes - individuals - who freely chose to form the supply chain. It’s like he’s imagining the economy as a voluntary global Woodstock festival, with millions of solo workers hiking in across the fields with peace flags to spontaneously combine their labour into a single concentrated pencil, after which they pack up and walk off on their own.

The reality is different. The pencil is certainly created by a massive chain of people, but each of them is not fundamentally free, because there is no option to ‘walk off’ and not be part of the meta supply chain any more. There’s no fundamental ‘independence’ that precedes and follows acts of interdependence. In fact, what we call ‘independence’ is just a secondary phenomenon situated within the strictures of interdependence. It can mean one of two things.

It can refer to having relative power within an interdependent system. For example, when a parent says ‘oh my son Julio is now independent’, what they’re really saying is ‘Julio is able to seek out and connect into other people without my help’. The fact that Julio can drive in his new Toyota to get fuel at the gas station is not evidence of some authentic ‘independence’. It’s evidence of his ability to call in the interdependent economy, in the form of Japanese auto workers or Saudi Arabian oil workers

‘Independence’ can also refer to that situation where you temporarily detach from one position in the interdependent system to seek another attachment point. For example, when you leave a job you’ve been at for a long time and say ‘I’m going independent’, you’re basically saying ‘I’m leaving the relative security of one entanglement and I hope I can find new entanglements in my freelance position’. As any struggling freelancer knows, nobody truly wants to be ‘independent’ of others for any length of time, because - well - that means you have no work and no food

The day-to-day operation of any economy involves maintaining ties of interdependence, and the main thing that changes over the course of economic history is the style of interdependence. In many ways these styles resemble our aforementioned attachment styles. All economies will host a variety of these ‘attachment styles’ at any one point, but they often have a dominant one that structures the others. Let’s look at these in very simplified broad-brush strokes.

1) Secure economies: hunter-gatherers and tribes

Ancient hunter-gatherer bands, and many pre-capitalist tribal groups had a relatively ‘secure’ style of interdependence. A Hadzara teenager, for example, won’t have to suck up to a boss to get into the communal hunting band. Rather, they follow the custom, and go through an initiation ritual or rite of passage to be inducted in. Once they’re in, they’re in. This isn’t to say that life in that position will always be easy - there are other forms of insecurity in that context - but they’re not on the verge of being thrown out of the society (‘unemployment’), so there isn’t a strong sense of having to compete to stay in it.

2) Anxious economies: slaves, feudal societies and caste systems

What is a slave but someone held tight into a toxic bond that cannot be broken? Slaves are certainly in a system of interdependence, but it’s highly unequal and unbearably clingy. You find this clinginess more generally in feudal societies and caste systems, where people are heavily bound together in anxious co-dependent hierarchical layers. The peasant prostrates himself at the foot of his lord in a show of fawning allegiance. The lord stays aloof, but deep down he’s also clingy and controlling (‘you must ask my permission before you can leave for your pilgrimage’).

3) Avoidant economies: the borderlands

An avoidant economy means one in which people keep distance and only partially depend on each other, but even remote ‘self-sufficient’ subsistence farmers have small networks of interdependence between themselves. You can avoid economic entanglements to an extent - and nowadays you’ll find the occasional wilderness survival guy who lives in the forest - but the original wilderness survival experts were hunter-gatherers and tribal groups, and the members of those groups didn’t avoid each other at all. They might, however, have an avoidant pattern when encountering other groups.

Avoidant patterns are common in the interstitial zones between economic networks. For example, in early colonial times in South Africa, Xhosa tribal people had one system - pastoral herding - and European settlers were plugged into another - global market capitalism. Xhosa people would certainly do trades with the foreigners, but this took the form of both parties temporarily approaching and then backing away, which is an avoidant pattern.

All that changed, however, with proletarianization, in which Xhosa herders got increasingly pushed off the land (undermining that means of survival), while being forced to pay colonial tax, which made them increasingly dependent on monetary wage labour, which merged them into the dominant network. Once dependent on the dominant network, a pure avoidant pattern is no longer possible.

4) Anxious-avoidant economies: market capitalism

Libertarian accounts of capitalism often fixate on the avoidant pattern - the fact that you can approach and then back away in a market. It’s a bit like they imagine you to be a Xhosa pastoralist in pre-proletarianized South Africa, voluntarily entering into an exchange with a Dutch merchant to get cotton cloth, before you back away into the hills.

In the actual case of South Africa, though, the Xhosa person exits into a different interdependent system - tribal society - whereas in the hypothetical thought experiment of libertarianism, the person just exits to individualism. They’re living in the hills by themselves, floating around waiting for their next voluntary possibility to trade.

This loosely feels plausible, because it’s true that in a large-scale market society you can feel like you’re a lone wolf on your own, bumping around the market, but that’s the surface appearance, not the deep reality. The vast majority of people have no land or tribal society to exit to, so there is no exit point, and no possibility of a fundamental ‘detachment’.

The reality of a market system is that we’re all fundamentally attached, but we all have (greater or lesser) ability to briefly detach to reconfigure which particular path of attachment we’ll take. To give a simplified example, the same global supply chain for wheat might feed into two different makers of bread, and they might distribute to two different retailers, leaving you with four possible attachment points to that single supply chain (Hovis bread at Sainsbury’s, Hovis bread at Tesco, Warburton’s bread at Waitrose, Warburton’s bread at Lidl).

A market society is a system of fluid, modular, re-combinable large-scale interdependence, and this characteristic applies both to people who are trying to get the outputs of the chains - a person trying to consume something - or a person trying to be an input to them - a person trying to get a job. Unlike a tribal teenager, though, a young person in our economy has no ‘rite of passage’ that gets them a secure place in the structure. Nobody is obliged to attach to them, but if they don’t the young person is screwed, because they have no land to return to (well, they have their parents to return to, but their parents in turn must have a job). This means a young person entering an economy will become incredibly clingy, prostrating themselves before bosses (people who own concentrations of assets) begging for a chance, promising fawning allegiance. That’s a highly anxious pattern.

Once you find a way in, though, you still have to fight or compete to stay there, because the boss, or the client, or whoever, can always detach you. Neoliberal governments put a romantic spin on that, saying stuff like ‘we want to promote competition, because it creates innovation and helps the consumer’. What they’re saying is stable attachments create security and security creates stagnation. You must have the constant threat of being cut off from your life support to keep you on your toes.

The imagined person being served by this competition is the consumer, which is… well… you when you leave work. The imagined ‘empowered consumer’ is supposed to be avoidant - as a shopper you can ‘take your business elsewhere’ at any point, exiting the entanglement with a particular producer. That sort of feels like ‘freedom’, but you cannot stay detached from others forever, because… well… they make your breakfast cereal and you’re not a Xhosa pastoralist or wilderness survival guy, so you have to always reattach. Switching from Hovis at Sainsbury’s to Warburtons at Lidl isn’t a fundamental rejection of interdependence. It’s a temporary moment of avoidance to create a cosmetic change to the attachment path.

At a meta level, this dynamic creates an anxious-avoidant pattern in market society. To be that avoidant consumer, you need to be that anxious producer for others - you need a job - but if others refuse to attach to you (aka. if you’re a producer and they’re acting out the avoidant consumption pattern), you’ll feel existential terror, and cling to the connections for dear life.

Ideology for the anxious-avoidant

Once you can see this pattern, it starts to explain many elements of economic politics. For example, big corporations want workers to be loyal, but they hate it when workers are clingy, because they want to be able to detach them at any point. Workers will feel this constant potential of abandonment, but so too will corporate managers, because corporate shareholders can detach from them at any point (see A Lego Model of Corporate Capitalism).

This can push people towards dickish behaviour to secure their position (see the Inner Civil War), which helps us make sense of those ‘it’s a dog eats dog world, so eat or be eaten’ mantras. That feeling of having to fight others to survive is kinda perverse, because it’s others who keep you alive, but this is what you’d expect in an insecure system. So, we might find a young manager trying to undercut his way to the top by encouraging workers below him to undercut each other.

The lived experience of this is what working class union movements sought to combat. Their message to workers was: you are not alone, and we should not fight each other. You are a part of a collective with rights and we will stand up for you. That solidarity vibe was what the Thatcher government wanted to destroy, because - as mentioned - corporate bosses hate clingy workers, and unions give workers more power to cling. Unions are disrupting the workings of the anxious-avoidant pattern, where the anxiety of one party triggers the avoidance of another.

Thatcher then, was working on behalf of corporate bosses when she broke unions. This is framed as a revitalization, because corporations feel constrained or ‘stagnant’ in the clingy worker embrace. To present the destruction of that embrace as empowering, neoliberals had to create a utopian picture of the empowered avoidant consumer, the person browsing the shops with endless choice and freedom (i.e. you will lose your job security but enter a product utopia). Corporates, however, dislike avoidant customers, so don’t want the utopia to become a reality. They want clingy customers who fawn over their products, which is why they saturate our environment with advertising and seek to entrench themselves as unavoidable infrastructure.

In any case, as worker solidarity dissolves and the product utopia is pushed at you, people are left to face the economy in an atomized position. This gives fuel to four flavours of libertarianism, two of them everyday, and two of them elite.

1) Everyday experiential libertarianism

The first is a kind of experiential libertarianism, which is just the everyday feeling of being alone in the economy. Regardless of your political ideology, you’ll probably find yourself believing that - at a deep level - the economy is a place of alienation and isolation, rather than inclusion and communitarianism. This can double as a feeling of powerlessness to shift the structure, because what can one person do?

2) Everyday self-help libertarianism

In sociology, Labeling Theory explores how people try to repurpose negative labels that get plastered on them. For example, if an unsympathetic teacher repeatedly tells a troubled kid that they’re a no-good waster, the kid might eventually shout back, you’re right, I am, and you can go hell! Similarly, when you’re in a society surrounded by messages and experiences that say or imply ‘you’re on your own’, one response is to defiantly say ‘you’re right, I am!’

That implies one pathway: change yourself rather than change society, and this is where self-help libertarianism kicks in as a type of emotional response. You cover yourself in a shield, give yourself ‘harden the fuck up’ pep-talks, and emphasise self-discipline and keeping a positive mindset.

You’ll see a lot of this kind of stuff in the Joe Rogan-esque ‘manosphere’ influencer scene: Should you be taking steroids for the optimal body? How to life-hack your way to success. How to earn passive income for minimum effort. How to sound interesting at networking parties. How to exude an aura of control and confidence. How to trade crypto to beat the market. How to self-optimise through meditation etc etc.

3) Elite euphemistic libertarianism

There’s nothing inherently wrong with giving yourself pep talks and learning new skills, but it gets insidious when it’s mirrored by forms of elite libertarianism that the beneficiaries of our system push out to those who are screwed by it. If it’s true that there’s systemic insecurity and inequality in our economy, those who are doing well have an interest in claiming that it’s natural, unavoidable, and even fair.

This leads to euphemistic libertarianism, where the unequal relations of entanglement in our society are presented as voluntary, un-entangled, equal and even harmonious. In this version, every market transaction is assumed to be a mutually beneficial interaction between two empowered individuals who are under no obligation to do anything or seek anything. Their lives are spacious and relaxed, which means there’s no pressure, duress, duty or hierarchy that infringes on the vibe.

In this framing, there’s no such thing as being exploited at work, because a labour contract is between equals who agreed to the terms, and therefore it must be fair by definition. The fact that a worker stays in a low-paid job must mean they’re happy with it, because of course there’s no requirement for them to stay, because it’s not like they’re facing systemic pressure of any sort.

You can see this vibe in the earlier pencil video with Milton Friedman. As he gives his romantic account of the supply chain, he’s making a political statement too, which is: this structure was created by willing, free and equal participants, and any attempt to meddle with that will break it.

That’s the euphemistic message at least. The deep underlying message is do not do anything to shift the anxious-avoidant character of our system, because any attempt to create a more secure attachment style will destroy the ‘natural’ pattern.

4) Elite arsehole libertarianism

Euphemistic libertarianism can be used by elites as a cloaking strategy for exploitation, but an alternative strategy is simply to neutralize any accusation of exploitation by owning it, and saying it’s the way things should be.

Remember that many people are pushed towards arsehole behaviour to reach a position of security in an insecure system, and they often do need a justification once they reach there. If you say to them you’re an arsehole, they come back and say: you’re right, I am! I’m rich because I’m stronger than you, and you’re weak and undeserving. Nobody owes you anything and every man is an island, so you only have yourself to blame if you’re failing. If you have a problem with a corporation, just stop complaining and build you own, weakling.

This hard shell though, is underpinned by insecurity. The person feels a overweening desire for control in the face of fluid market interdependence, and imagines that a successful person is one who has mastered destiny to carve our their own secure, fortified, personal island of stability. They must believe that their island is ‘self-made’, and that anyone struggling in the waves is receiving their just desserts.

Perhaps the ultimate pop culture expression of this was the 2014 Cadillac ELR Coupe ad. In it, a stereotypically successful American man with a wife, kids, ripped body, big house and big modern Cadillac, strolls around with his balls swinging, talking about how hard-working, confident and badass he is, and how he revels in not taking holidays like the lazy Europeans.

This kind of thing appeals to a certain type of person, but from an economic perspective it’s totally bogus. He’d be reduced to humbly begging on his knees in a week if the workers who produce his food stopped working. Every object in his life is built by other people, and they’re almost certainly not living in the style that he is. What’s happened here is that he’s manoeuvred himself into the upper echelons of the economic network, but he requires others to be in the lower echelons to produce all the things he gloats about. I mean, it’s not like he’s going to get dirty to produce the raw materials and components of a Cadillac, is he?

The fact that he’s trying to now claim that everyone in the structure can be in the same position as him if only they work harder is a fallacy of composition. If everyone actually was in his position, he’d have none of his stuff, because nobody would be there to build it. He, however, has a natural interest in projecting this smug aura, because if he let go of control and entertained the possibility that perhaps he benefits from an unequal system, his self-identity crumbles.

But let’s get real. This guy is an actor, and the actual producers of this were the bosses of Cadillac, who’re using arsehole libertarianism as a marketing message, but also as a shaming strategy to anyone who has doubts about inequality and the lack of holidays in the US. It’s no secret that business elites like the Koch brothers are behind many of the original conservative libertarian think-tanks, but these individualistic self-help stories are not supposed to actually describe our system. They’re supposed to be a numbing pill for elites, a shaming weapon against critics, and a comforter to people in lower positions.

The primed mind

Perhaps that’s OK if it helps you survive, but it can also horribly backfire and mess with your ability to understand the basic realities of the economy. It will also control your mind in various ways. Have you noticed, for example, how a lot of the conservative bro-verse automatically gravitates towards stories of commodity money like Gold and Bitcoin? That’s not because they’ve sat there and analysed monetary systems. It’s because their minds are required to go that way by the underlying ideology they’ve taken on.

What do I mean by that? If you truly believe that ‘every man is an island’, you’re going to have to develop mythology about what connects the islands together, and that mythology will lead to a particular Platonic Ideal of what money is, or what it’s supposed to be. That ideal will leave you unsure about how to explain the actual monetary system - so you’ll have to use various straw-man descriptions of it - but it will also leave you susceptible to believing the marketing material of the gold and Bitcoin industry. I’ll elaborate on this in my next article. See you then.

Good piece Brett. Neoliberalism is a kind of social carcinogen. It eats away at the norms and laws that make healthy communities possible. Forty+ years of rampant neoliberal ideology have led to the rapidly metastasizing malignant community degradation happening now in the US. Curiously Karl Polanyi essentially elucidated this process in 1946 in “The Great Transformation.”

Great piece. "I have a long and complex history with libertarianism, because - socially and emotionally - I’ve often come close to its ideal. I’m what you might call a lone wolf, someone historically wary of social ties." Totally. George Sand used to say this about herself. She learned to live with the contradiction - weary of society even when one must advocate for it - after the failure of 1848. You might like some of her letters at the time!