Paying subscribers can find the audio edition here (30 minutes)

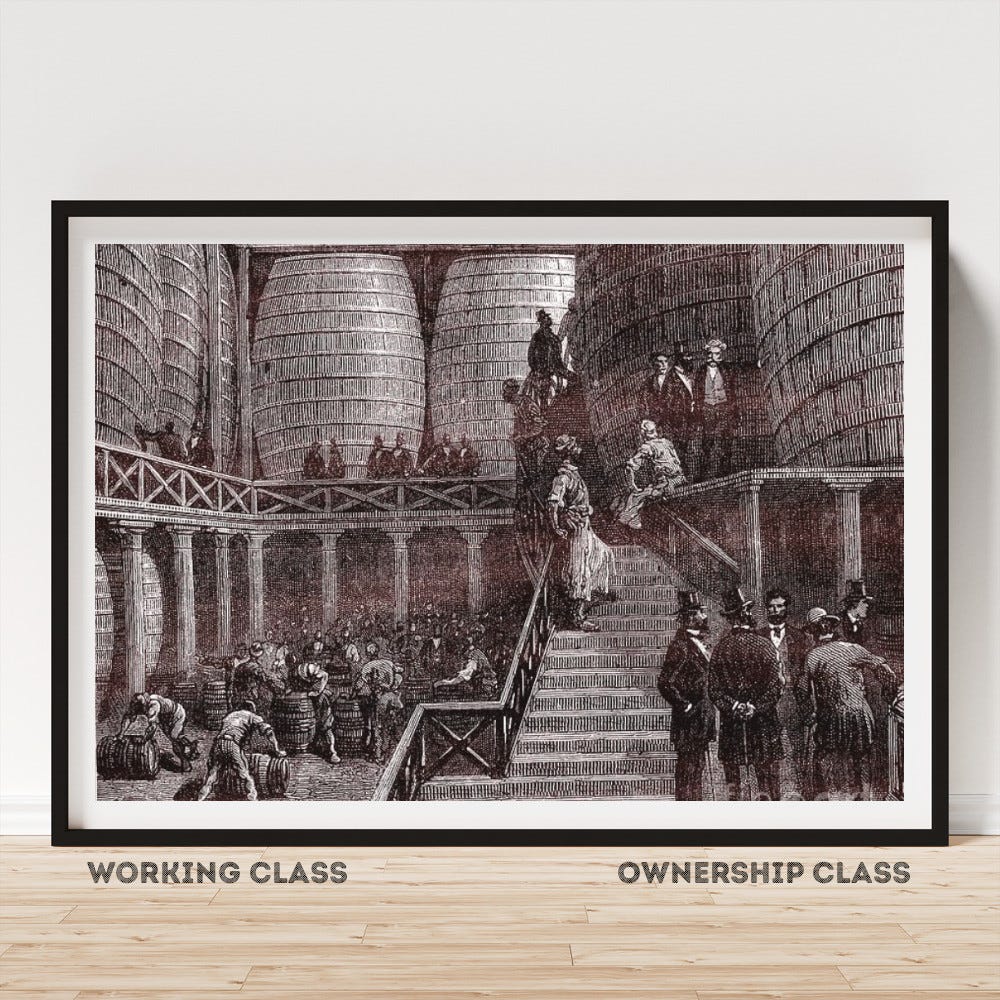

19th century Marxists had one thing in their favour. The battle lines in an economy were clearly marked, so they could speak about a simple clash of classes. After European feudalism disintegrated, dispossessed peasants had drifted to the cities to become the urban ‘working class’, a group of people who owned nothing, and who often had few other options but to sell their labour to an ownership class - rich people who controlled factories.

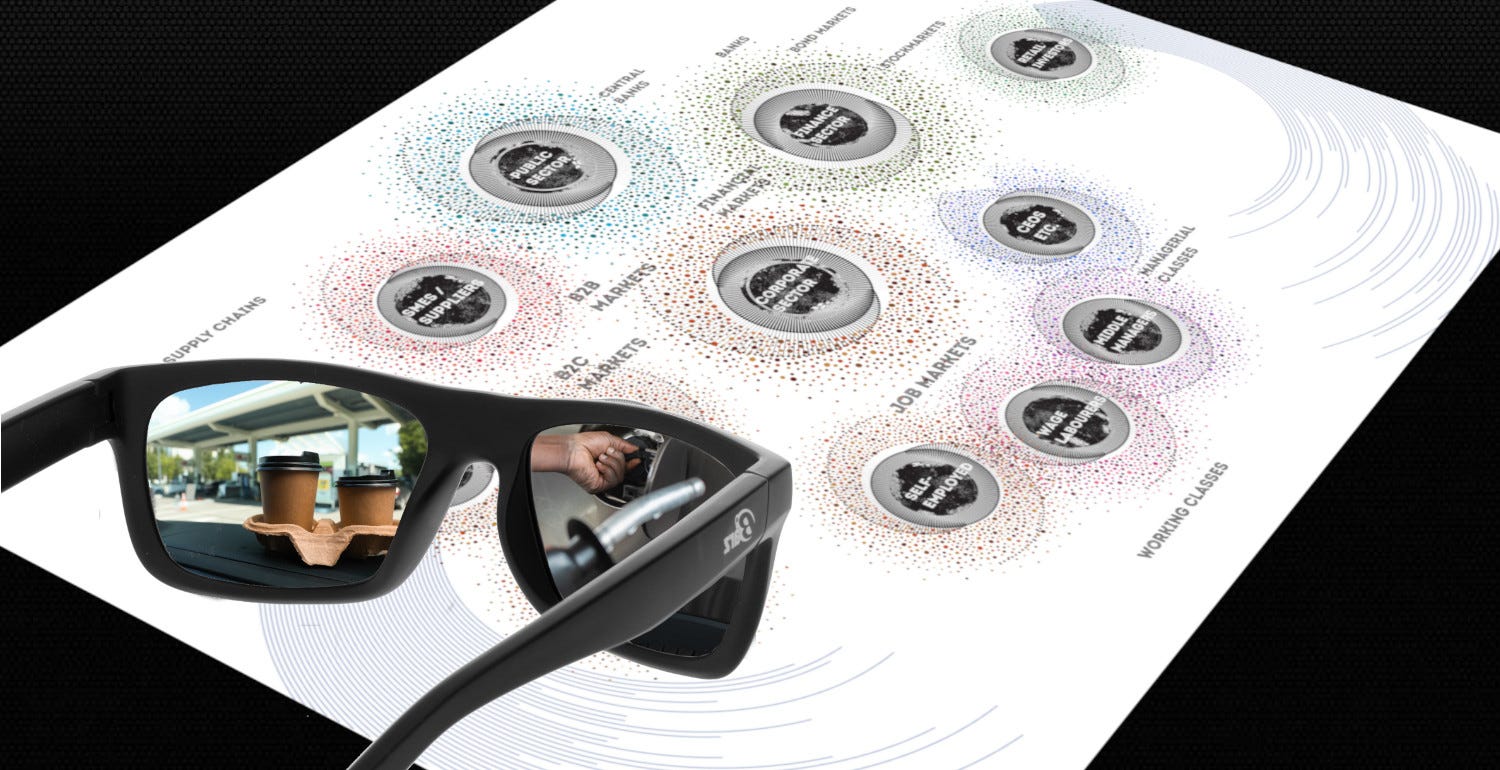

In my Stone Soup Theory of Billionaires, I expanded upon these basic battle lines, showing a more modern version. If we had take every single activity in the global economy, squash it together, and imagine the entire thing as one giant process of people collectively making a huge ‘soup’, we could split the whole enterprise into five basic classes:

There are those who own the pot - shareholders

There are those who direct the cooking - managers

There are those who bring the ingredients and make the soup - workers

And, finally, there are those who eat it - consumers

We can also add in the state, which underpins the entire legal and contracting structure of the enterprise

This is of course an abstraction. It’s not like we literally have a single giant pot and it’s not like we’re literally making a single soup in a single state. Rather we have hundreds of thousands of smaller ‘pots’ - productive units we call companies, spread across the world - and we are producing many different types of things against the backdrop of a mish-mash of different state regimes. To gain clarity on the overall structure, though, it’s helpful for us to imagine those combined into a single pot with a single soup and single classes of people revolving around it.

That last class - ‘consumers’ - is the most all-encompassing, because it’s made up of all the other classes. In the end, if you don’t eat, you die, but some get to eat a lot more than others. Shareholders, managers and workers will all be consumers, but they don’t consume the same amounts.

Actually, that term ‘consume’ is a little misleading here. In reality, the biggest inequality that builds up in our system isn’t so much consumption, as it is the right to consume. We have people with vastly unequal amounts of claims upon the soup.

This is a tricky concept to initially understand, but in my Stone Soup article I explained it through the metaphor of soup vouchers. When you zoom out to the most meta level, you can observe a basic three-part circuit in a capitalist economy that repeats itself:

The financial sector as a class - in conjunction with the state and central banks - creates (and accumulates, via step 3 below) ‘soup vouchers’ - rights to eat soup

It entrusts these to the managerial class, who will hand out some portion of those to the working class - hiring them - in exchange for those workers making the soup

Anyone who eats the soup - whether they be shareholders, managers, or workers - will hand in vouchers to get it, which will get passed back via the manager class to the financial sector

I’m obviously simplifying the picture, but what do the vouchers in this metaphor stand for? Yes, you got it: money!

The reason why Jeff Bezos gets $7.9 million an hour - regardless of whether he’s playing golf, or meditating, or in a meeting - is because Amazon workers are ‘producing soup’ - delivering packages etc. - for people who are ‘consuming soup’ - those who are handing over ‘soup vouchers’ for packages - meaning that the residual is accruing to the owners of the pot: e.g. Bezos.

In reality, Bezos does not have the physical ability to actually cash in his soup vouchers. After all, if you made $7.9 million an hour, would you be able to spend it? Maybe you could manage for the first couple days, but soon it would become an exhausting activity. Even if Bezos had an entire team dedicated to spending his money on a 24-hour basis, they’d probably only get through a small fraction of it. So, he just lets the vouchers roll in, accumulating a vast war-chest of claims upon the collective soup. This is how they become billionaires.

There’s a whole class of people - in think-tanks, economics departments etc - who dedicate themselves to building ideology for people like this. For the last couple hundred years they’ve created a whole series of justifications for why shareholding and managerial classes accumulate so much. We know these stories well. The billionaire, or the titan of industry, or the highly paid hedge fund manager, is just someone who is more talented, more hard-working, more visionary, or more risk-taking than anyone else. Apparently, they create jobs, and apparently without them we’d all be lost. This was at the core of Ayn Rand’s philosophy. Her famous book is called Atlas Shrugged, in reference to brilliant individuals who supposedly the world up on their shoulders.

These stories get passed around as common sense in any kind of mainstream entrepreneurial, financial or business executive scene. They draw upon the moral concept of just desserts: in these accounts, the sheer amount of claims on soup that are controlled by the wealthy is due to their enormous contribution to society, and critiques of this wealth are just the result of jealousy, or envy, coming from undeserving lay-abouts.

At the risk of mixing metaphors, this ‘enormous contribution’ is a bit like the contribution a beekeeper makes in the creation of honey. A beekeeper doesn’t actually make honey - bees and flowers do - but the beekeeper can say ‘I instigated this’ or ‘I inspired the bees’, or ‘without me the bees would be directionless’, or ‘my particular hive structure brings out the best in the bees’ and so on.

We can debate the relative merits of these arguments - some beekeepers are definitely talented, and do find ways to get more honey out of the bees, and the bees might even be grateful for a particular hive, but in the case of capitalism this situation has historically been volatile. That’s because the bees might develop some kind of swarm consciousness in which they decide they no longer need the beekeepers.

In other words, if workers could form a sense of themselves as a single class with a single set of interests, they might band together and threaten the overall structure. This was the ‘Communist Threat’, the potential for a rising swarm of workers who could overthrow the hive owners (or alternatively, in the case of the cooperatives movement, just form their own hives). This is why Dickensian capitalists would hire thugs - like the Pinkertons - to root out ‘agitators’, who might try to… well… agitate the bees into action.

In places like the UK and US, those swarm formations were spearheaded by the unions. To get a quick feeling for union life, listen to Part of the Union (1973) by the Strawbs. The video is accompanied by imagery from the 1984 Miner’s Strike in the UK, where agitated workers faced up against the authorities.

The classic union weapon is strikes, but that in turn attracts the classic beekeeper counter-attack, which is to turn the public against the strikers by presenting them as selfish disruptors who are harming all the other hard-working bees in different parts of the system, who just want to make and consume honey with their families (or, if we pivoted back to our soup metaphor, imagine them saying “you’re ruining the soup for everyone else!”)

So, in the 1980s we saw the rise of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, who wanted to break the union threat once and for all. Thatcher used a combination of violence and enticement to do that. The violent side was getting the cops and the law to forcible crush the unions, but the more subtle side was ingenious. Thatcher knew that the best way to fight resistance to the structure of capitalist relations was to spread a person across the battle lines. As long as workers were united as a group, and had a coherent personal identity as a worker, they would be able to identify each other, come together and cause shit for the ownership class.

If, however, their inner identity was slowly warped to have conflicting parts, then their ability to unite would be damaged, and resistance would be diluted. The key was to introduce an inner capitalist into their being that would fight or suppress their inner worker. And, the key to doing this was to encourage them to get little slices of ownership in assets - whether that be a house, or shares in the stock market as retail investors.

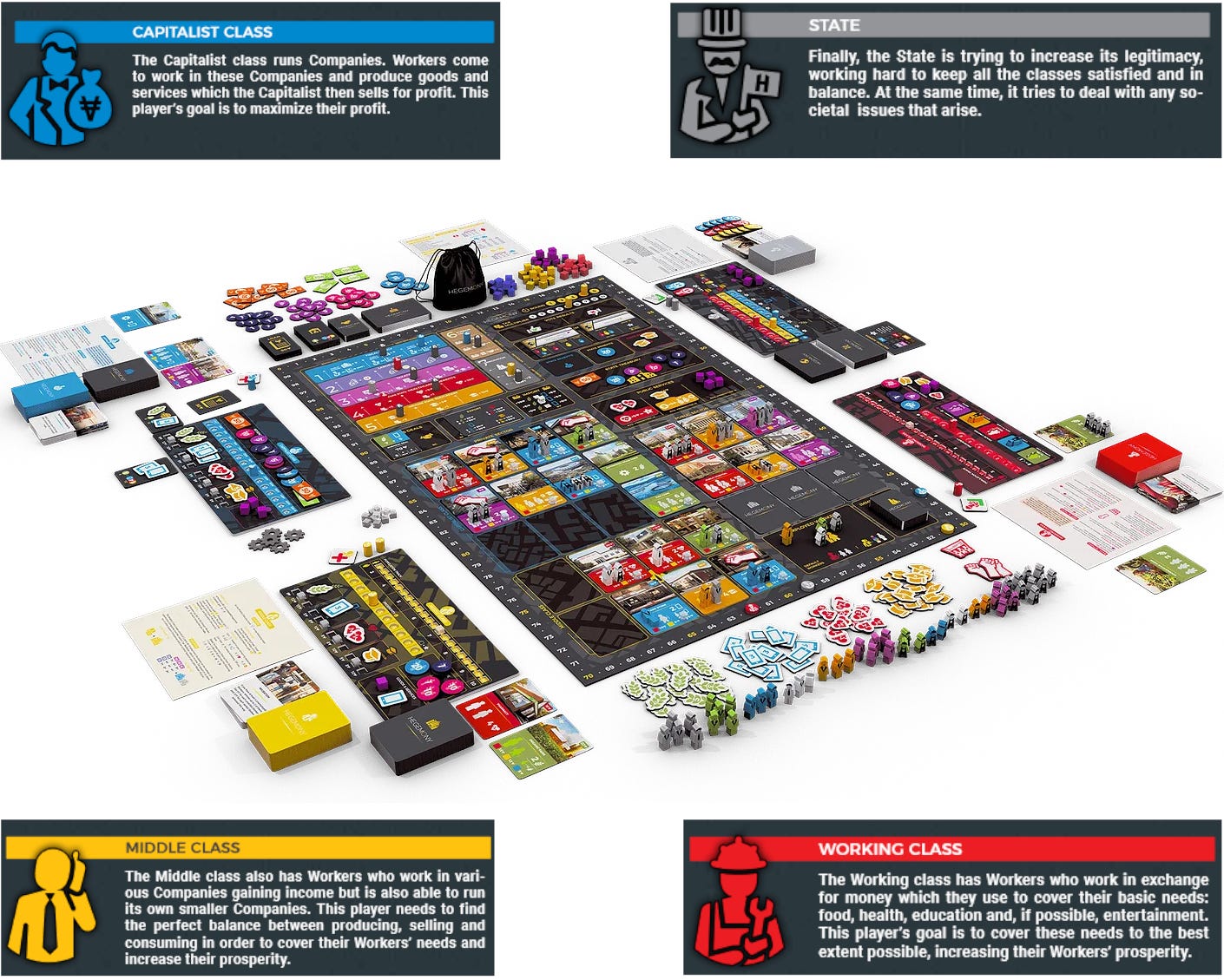

Small-scale asset ownership like this is a key feature of what’s called the middle class, a kind of buffer zone between capitalists and workers. If you want a gamified experience of this, I recommend playing Hegemony, an (admittedly complex) four-player board game released last year, in which different players take on the role of capitalists, workers, the middle class and the state, each with its own objectives.

A key feature of the game is the political voting system: players have the ability to fight for favour from the state and introduce legislation to enhance their class interests. The strategies for the capitalists and workers are quite straightforward - it’s a well-rehearsed battle between old rivals - but the middle class is the most conflicted, constantly trying to hedge their bets.

In fact, in the case of the middle class, the battle increasingly takes place within. A person occupying that hybrid position - or seeking to occupy it - can come to have a fragmented series of internal personas get played off against each other.

For example, perhaps you’re paid too little at work, and are worried about the cost of living, so you seek to compensate by making money in the stock markets. Rather than ‘handing in soup vouchers for soup’ - paying for goods - you recycle money back through the financial sector to buy shares in companies that are run by managers that believe they must boost profits by paying workers less while charging consumers more.

See what just happened there? One part of yourself seeks to benefit from the suppression of two other parts of yourself.

This system of inner conflict has spread everywhere now, even to working classes. After all, with unions broken, and workers often fragmented via gig economy systems, it’s hard for them to imagine collective action. In that context, gambling your way out via stock markets - or crypto for that matter - starts to look like liberation. If everyone else is trying to do it, you might be a sucker if you don’t.

To understand this more deeply, though, we also need to recognise that our system is so large that a person often cannot see how the parts relate. As I noted in Coming of Age in Corporate Capitalism:

… if you’re just a tiny node in this system, it’s like being subsumed within a vast maze where all you can see is the immediate surface in front of you

Like a maze, the economic system is a single system, but it looks different depending on where within it you’re standing at any particular moment. So, let’s take a high-level flyover through four of its classic viewpoints, and see what each does to you.

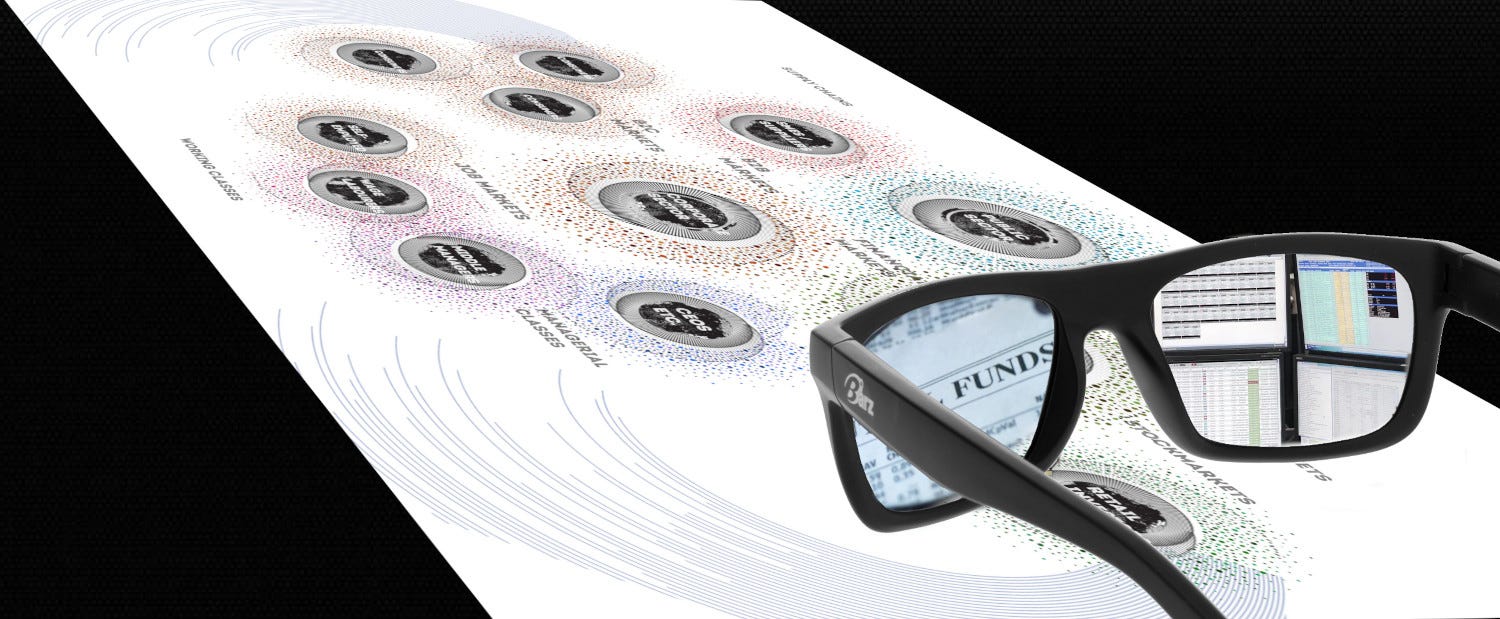

1) The view from the financial sector

As I noted in my Lego Model of Financial Capitalism, shareholders and creditors are different classes of investors who hand over money in exchange for contracts (shares, bonds etc) that promise them future money. Large institutional investors might do this directly, but our smaller ‘retail’ investors often go through an intermediary like a mutual fund.

Retail investors hand over small amounts of money for small cuts of financial instruments, and may do this to save up for their future retirement, or perhaps because times are tough and they’re choosing to save instead of spend. Regardless of motivation, many small investors imagine that investment is the act of ‘making money from money’. They might have been told that they can earn a ‘passive income’ without working by getting their money to ‘work for them’, but these phrases are euphemisms. What they’re really trying to do is get a cut of the profits derived from people’s labour (including, potentially, their own).

There are, however, many different routes to doing this. They may open a savings account with a large bank, or buy units in a mutual fund that buys bonds, or buy into a package of shares of different corporations through an index fund or ETF.

Alternatively, they may directly buy individual shares through a retail stockbroker. Perhaps they buy shares in the oil giant BP.

It’s possible that the person above could be a loyal long-term holder of the shares, but shareholders can also be fickle and short-term, in which case they’re called traders. Traders might repeatedly buy and sell shares as they try to guess the future trajectory of different companies. Buying shares technically makes you a part-owner of these companies, but sometimes traders don’t even look at the firms. Instead, they might make their decisions by watching what other traders are doing, as represented by abstractions on charts:

Smaller-scale retail traders are often called day-traders. Some of them sense that capitalism is a dog-eats-dog or eat-or-be-eaten world. Rather than fight that, they embrace that persona and build a heroic view of themselves as seeking to beat the market. The short video below captures this mentality perfectly.

Day-traders are often people who want to transition away from working day jobs, and you’ll note that the video is created by a company called OpenTrader, which is a training platform that tries to convince people to ‘join the movement’ to become like this. Of course, if everyone actually did become a full-time day-trader, there would be nothing produced in an economy, so all share prices would go to zero.

This idea of small-scale financial trading being a source of economic liberation is very common (in fact, it extends back a few hundred years), but in reality small traders are tiny parts of the broader finance ecosystem. The platforms they use will be run by much bigger players that benefit heavily from the day-trader’s (often futile) attempts to beat the market. I know this, because I actually once worked in a spreadbetting company (after working in large-scale derivatives markets), and the marketing team would explicitly attempt to cultivate this mythology of the day-trader to scrape fees from them. Most vulnerable were mid-level professionals, who had both savings and the hubris to believe they could outgun the world’s most powerful financial institutions.

Many large-scale institutional traders have a self-image of being engaged in productive activity, and frequently assert that the economy would fall apart if they weren’t there to ‘provide liquidity’ (aka. move soup vouchers around). That said, there are new generations of small-scale day-traders who have a more nihilistic streak, aware that the financial system is largely an unproductive extraction game, and who seek to get a slice of that. If you’d like to watch a great documentary about day-traders attempting to temporarily reverse the power hierarchy like this, I recommend watching Eat the Rich: The GameStop Saga.

Despite the David vs. Goliath swagger of the meme-stock activists above, these small-scale investors have very little power relative to the world’s largest financial institutions, like commercial banks, hedge funds, private equity funds, pension funds, insurance funds, and sovereign wealth funds. For example, the documentary above looks at Citadel LLC, a hedge fund which manages almost $60 billion on behalf of rich people.

Major funds like this are in symbiosis with major investment banks, which deal in ‘wholesale’ chunks of corporations, rather than the small retail slivers that day-traders work with. Despite these differences in power, investors share some common viewpoints. They’re betting on a whole range of unpredictable interactions in the different parts of our ‘soup-making’ picture, but care about it only from the perspective of how many ‘soup vouchers’ roll back to them relative to how much was put in.

This means, through their eyes the world is often rendered as a series of price charts and graphs, and within this schema, workers are just numbers that appear on a company income statement as expenses that detract from profits. Minimizing these expenses is seen as positive, which means driving down wages, automating away jobs, and cutting corners with suppliers can implicitly be seen as positive too. Furthermore, in the finance worldview, consumers are not seen as individual people, but rather as an abstract collective that will give rise to future revenue.

When deciding whether to invest, the investor might create a thought experiment in which they guess how much the consumers will buy in future, and set that against the expected expenses of workers and suppliers. They can put the result through a ‘discounted cash flow analysis’ to give them a theoretical price for the shares. They can then compare that to the actual current share price to see if the shares are ‘good value’ or ‘overvalued’.

When making these projections, investors are not only imagining what returns they may get in future. They’re also setting that against potential risks. This leads to a risk-return mentality: If they back a risky venture, they want a higher return. Through this lens, they’ll get agitated if they’re not making enough profit relative to the risk they’re taking on. They’ll also get agitated if they’re making less profit than they could get somewhere else for the same amount of risk, or if they sense distant threats like future government regulations, worker activism or consumer boycotts. Of course, they can also make absolute losses when things go badly at a company, but also if there’s simply a change in sentiment in the financial markets that drives down share prices that were previously based on unrealistic projections.

This gives a peculiar quality to the relationship that shareholders end up having with senior corporate managers. While major shareholders are supposed to keep an eye on managers, they also don’t want managers to disrupt any unrealistic dreams that might be upholding a particular share price. This pressure to keep stock prices up can lead managers into short-termism, where they try to boost the profits of a company by cutting corners, ignoring environmental damages, doing dubious financial engineering or resorting to accounting fraud. Let’s now turn to this managerial class.

2) The view from the managerial sector

CEOs and other senior managers share various aspects of the financial world-view, because they’re technically hired by the shareholders of firms, and also because they often hold shares themselves (e.g. as part of their compensation package). This means, they always have one eye on the broader financial markets while they try to manoeuvre the workers and assets of the firm, seeking to maximize shareholder returns while minimizing risks. In my Lego Model of Capitalist Central Planning, I delve deeper into this.

The CEO delegates the different moving parts of a firm to different C-suite sub-managers, who might specialize in securing finance, hiring people, dealing with supply chains, buying up assets, making strategic decisions and targeting new consumer markets. All these senior managers share certain common stresses and tendencies. Most notably, they’re sandwiched between shareholders and workers, but are contractually required to prioritize the interests of the former.

Profit emerges if input costs are lower than output revenues, (aka. if they hand out less soup vouchers than they get back), so to reduce the former managers might seek to drive down worker wages and dominate over suppliers, but their workers might be scattered across the globe in distant operations in Nigeria or Australia. Each country they operate in might have separate union laws, environmental regulations (or lack thereof) and labour conditions. So, being a senior manager in a transnational corporation is inherently geopolitical. They might be cutting tax deals with different governments, or lobbying against new policies that may affect them, all while trying to suppress worker unions. Here’s a consulting company that literally offers services to do that:

Another way to discipline workers is to replace (or threaten to replace) them with machines that managers can buy from external suppliers (automation). At the same time, managers might face pressures to keep stability, and that may involve trying to reward loyal workers. It doesn’t always pay to fuck over your workforce, especially because cutting input costs isn’t the only way to increase profits. They can also boost output revenues by trying to break into new markets or to capture more consumers via marketing (hence our world being saturated with corporate messaging).

Above all, managers will often become paranoid about fending off other managers who coordinate other companies. After all, they face humiliation if they lose market share, and may even face getting fired by the shareholders for failing at their task. We seldom feel sorry for these senior managers, especially because they get paid millions, but they often project their own stress downwards to more subordinate middle-managers.

To this day, one of the most entertaining series that covers middle-management life is The Office (US). The series follows Michael Scott, the hapless branch manager of a regional paper corporation, as he tries to be a nice guy that keeps his workers happy while he faces top-down pressure from ‘corporate’ (the name he gives to the distant senior management).

3) The world through the eyes of workers

The big shareholders and senior managers of companies often like to claim that they create jobs, as if they were handing out some kind of charity, but they create jobs in the same way that a beekeeper does. The people sitting around the boardroom make nothing unless workers actually operate their assets, but many workers don’t think like this. They’re often in a weaker economic position, lacking access to capital and having smaller buffers of money to survive on. That means they indeed may feel grateful if they can secure a job operating corporate assets.

This is especially the case when there’s a limited number of possible ‘hives’ (after all, not every bee can run its own hive, or if they did, they’d be tiny, lonely, ones). This means the workers have to often compete against each other for limited slots. They may become fearful of other workers who are competing for positions to work the same assets, and this can bleed into xenophobic fears around immigration, or fears of foreign outsourcing. In the 90s there was a major wave of globalization, in which big corporates started firing local workers and delegating their roles to foreign suppliers.

External suppliers also bring another source of anxiety: they can sell automated machines to the managers, leading to fears of machines, or robots, ‘taking jobs’.

Many of us know what it’s like to be in this situation. Workers face pressure from bosses telling them what to do, and hear whispers about elusive shareholders who don’t directly speak to them. They’re often the ones that actually make the things that consumers will be buying (or the ones who serve those customers), but will often also sense that their bosses have more allegiance to those consumers than to them. For example, in the service industry they may find themselves reprimanded by a middle-manager who tells them ‘the customer is always right’.

As mentioned earlier, workers often find themselves pitted against consumers if they demand more from their company. Given that the managers and shareholders are often not prepared to lower their own cut, any increase in worker wages will be presented as ‘driving up the cost of living’ because it’s being ‘passed on to the consumer’. This of course would be solved if managers and shareholders just took a lower cut, but short-termist managers are scared that if they reduced the shareholder returns the fickle investors would back away.

4) The world through the eyes of ‘the consumer’

The world of the consumer is the world of commodity fetishism, where products appear before us on shelves, or Amazon.com pages, divorced from their underlying origins and contexts. The man below will not be aware of the transnational labour networks behind the oil that his fuel is derived from. He also won’t know that the same oil company - BP - might supply the oil used for the plastics in the lid of his takeaway coffee. He certainly won’t think about the fact that hedge fund analysts once probably estimated his behaviour and inputted it as an assumption on a discounted cash flow analysis.

If this man is also a small-scale shareholder, he may feel happy at a booming stock market, but the pressure to generate the profits that might have led to that boom might also translate into increased stress on his life as an employee, as he find himself driven into burnout to achieve those returns for a boss who is trying to please the shareholders.

That’s why he may get irritated if there are minor disruptions to fuel through strikes, but even if he recognizes worker struggles he probably won’t feel like he can do anything about it. After all, his own survival in the economy requires him to continue using coffee, cars and other common inputs that are required to ‘keep up’ with everyone else. He may be feeling the pinch of the cost of living, and even if he’s aware that - somewhere down the line - a community in the Niger delta is rising up against an oil giant that’s polluting the environment, he’s probably just going to default to doing what he has to do. Buy the fuel and don’t think about it.

The civil war

These are the basic battle lines of our inner civil war. It goes without saying that they’re exploited by political leaders. Like any war, there are ways to make peace between the different sides, and like any war there are ways for one side to win out over others. Unlike a normal war, however, the sides are all within ourselves, so that latter scenario might involve the destruction of some element of yourself. Whether or not you experience that destruction as liberation, really depends on who you are.

Fantastic article, journalism, research, and i love how you always tie it full circle into the bigger picture. Showing us the the parts, the sum of the parts and how they are all similar in their wants/needs/agenda but going at it different ways based upon their chess piece and location on the board. Contiue the great work, please look to spread your materials to school curriculumns

Superb article. Brings together a lot of understanding you’ve already given me and makes a lot of sense. Very shareable by virtue of being non-judgemental too :) great stuff keep at it!