Paying subscribers can find the audio edition here

In recent years there’s been a strong outbreak of the Great Man Theory of History. This is the idea that single powerful or inspired people create history and should be adored, or, on the flip side, reviled. Trump is obviously one of these people, but so too is Musk, Bezos, Putin, and so on. Regardless of whether they’re imagined as superheroes or supervillains, they’re often spoken about as if the future springs fully-formed out of them.

When you imagine that the course of history uniquely resides in single individuals like this, you also imagine that slight shifts in their decisions affect everything for the rest of time. They’re like the star characters in a great global soap opera, but one in which nobody else has any role but to watch them, and either praise or condemn their actions.

This same style of thinking is often applied to their wealth. The Great Man Theory of Wealth assumes that extreme riches are the result of inspired work that the person undertakes. If Bezos had not got up one morning in 1994 and had an idea for Amazon.com, we’d never have a global e-commerce platform. I mean, there are only 8.2 billion of us on the planet. Surely, the chances of a second person working out that you could match buyers and sellers on the Internet is incredibly small!

It’s always imagined that the Great Man builds something. He built a nation. He built a company. This isn’t the full reality. Here’s what actually happens: other people mostly build the thing, and the role of the Great Man is to be the focal point around which it’s built. To understand this, let’s turn to the parable of the Stone Soup.

Great Man and His Stone Soup

The old parable of the Stone Soup goes like this. A guy walks into a village and proclaims that he can make soup out of stones. The villagers are skeptical, but he has a pot, and tells them to light a fire underneath it, and to fill it with water. He chucks some pebbles and assorted stones in, while the villagers stand around waiting for the mystical soup to emerge.

After five minutes of boiling, he strokes his chin and says ‘you know, this soup would be even better with some onions… does anyone have any?’ A villager wanders off to find some, and returns, tossing them in. Then the man says ‘what would really add a kick is some garlic, ginger and salt’. Other villagers trundle off to go find those. He continues to make these suggestions, enlisting the villagers to contribute tomatoes, spices, soy sauce and duck breasts, until the soup looks like a delicious Tom Yum.

As more people are attracted to the circle forming around the Stone Soup, the more ingredients go in, and the more the adulation for the Stone Souper rises. By the end, he’s transformed into a kind of idol. Apparently, he created the soup.

The reality is far simpler. The villagers built the soup, while he just stood there acting as a central attractor around which they arranged themselves. Alone, he’s just a guy with water and stones in a pot.

Alone, Jeff Bezos is just some guy in a garage. By himself, Musk is just another wounded nerd who wants to be praised, and Trump is just a slightly outrageous old man, the kind of guy you bring to a dinner for kicks. In the end, through the eyes of the great universe, they’re fragile carbon-based life forms like any other. What they’re good at, though, is putting stones into boiling water, and asking people to gather around and stare into that.

That process of instigation is not the same as building. There’s not one line in the Amazon code-base written by Jeff Bezos. There’s not one iota of iron-phosphate in Tesla batteries mined by Elon. Hell, he didn’t even dream up the idea for that company. Another guy did, but Elon nudged him aside and got the villagers to focus on him instead. Similarly, Trump didn’t lay one brick in the Trump Tower. Thousands of workers did, like they’ve done throughout history.

This practice of ignoring the actual builders of things is common. Even the esteemed National Geographic claims that a single guy built a whole pyramid…

So, what does someone really mean when they say ‘Jeff Bezos built Amazon’? After all, Amazon.com is a sprawling infrastructure and it’s physically impossible for one man to ‘build’ that. What we’re really saying is ‘Jeff Bezos instigated an initial instantiation of the idea of Amazon, which others then built over time’. His true skill was having the right personality to walk into the village square and instigate the process. That might come from a degree of personal bravery and brilliance, but it could also equally come from narcissism, trauma, family expectations, training, or just plain random happenstance. Becoming a focal point isn’t an insignificant achievement, but it’s not an impossibly difficult one either.

It’s also a skill that works better when you have an existing support structure around you. For example, right now there are 6.6 million people living in refugee camps, and I’d bet that at least 100,000 of them have stone-souping skills, but don’t find themselves in the right situation to deploy them. By contrast, someone like Elon - who is from a wealthy South African business family - always had a reasonably high chance of getting traction on stone soup.

Regardless of whether you think being a Stone-Souper is a highly rare and brilliant skill, we can say one thing for sure: the idea that the power to create the soup resides inside the single Great Man is, frankly, ridiculous. What happens is that other people’s power channels through them. Let’s delve deeper.

The Primordial Soup of the Economy

In the parable, people are coming together to make a collective soup, and presumably they get to eat it afterwards. In many ways, this serves as a basic metaphor for economic production and consumption more generally. At its most primordial, an ‘economy’ is simply a mesh of people who - when viewed as a whole - come together to survive. For example, you may have orange juice in your fridge right now. The oranges, plastic bottle, and fridge components were not produced by you, and yet you draw upon them. And, somewhere else far from you, someone may be drawing upon things you’ve produced.

In fact, there’s no such thing as a person who survives alone. Even the most hardcore wilderness survival guy on YouTube is still using steel knives and basic clothing that was produced by massive supply chains involving tens of thousands of other people.

This basic principle - that we come together to survive - was true in the age of hunter-gatherers, and it’s true now. That said, while we are part of a transnational mesh of people coming together, it doesn’t mean you directly depend on every single one of them. Rather, you only draw on a small subset of them, but they in turn draw on other subsets who draw on other subsets, and so on. If you zoom out, and look at every chain of interdependence, you’ll see an enormous web of extraordinarily complex connections, with no beginning or end. All these ‘supply chains’ will entangle and double-back on each other.

That sounds very complex, but - when you pierce through the complexity - it can be boiled down to a simple fact: You provide things to a collective whole, and get to claim things back from a collective whole.

The Moral Logic of Reciprocity

One of our most primordial moral concepts is: if you contribute you can receive. This is the concept of Reciprocity. It isn’t the only moral principle we have in an economic system, but it’s one of the top three (see here for the other two).

In a hunter-gatherer setting, the reciprocity principle might be ‘you contributed to the hunt, so you get a portion of the meat’. In a soup setting, this would be ‘you brought some tomatoes, so you get some of the soup’.

Let’s imagine two people making soup together. We can represent the reciprocity principle through measuring scales. Let’s say one person brings tomatoes and garlic and then sets about making the soup, expending energy in the process. The metaphorical scales start tilting towards them, in recognition of the energy and resources they’re contributing.

If the other person was to just sit there and contribute nothing, and yet expect to eat the whole of the resulting soup, we might say that’s unfair. If, however, the other person does their side of the work, contributing ginger and potatoes and helping with the stirring, we say they’re pulling their weight. This causes the scales to revert back to balance.

Notice how, as the scales balance, the collective resources and effort that has gone into the soup has also increased, making it bigger and thicker because both contributed. This collaborative production gives rise to a fuller whole, which is better than its individual parts.

This now feeds into the concept of just desserts: how much of this whole does each person deserve? Well, each person contributed equally, so they rightfully get to claim half of this improved soup. In informal contexts, we normally don’t measure stuff like this - it’s tacit and in the background - but the moral principle remains.

In the kitchen setting above, tracing ‘just desserts’ is easy. Similarly, in a hunter-gatherer setting, it’s simple to see who is contributing. Furthermore, the sense of how much each can claim back is held in the collective memory. If someone has taken a lead role in taking down a big antelope, for example, the others might grant them the first pick of meat. They don’t get to take everything though.

These are small-scale settings, but even in a huge-scale market economy we find a similar basic moral logic in the mix. People contribute labour and goods to a collective whole, and get to claim labour and goods back from a collective whole.

A large-scale market system, though, has one major difference to a hunter-gatherer economy. Rather than claims upon the collective output being encoded in collective memory, they get encoded in money credits. If you have a lot of money, you get to claim a lot back from the collective sum product of everyone else. At some highly theoretical and idealized level, then, the amount of money you earn should reflect your overall contribution, and - therefore - how much you get to claim back from the collective ‘soup’ of the economy.

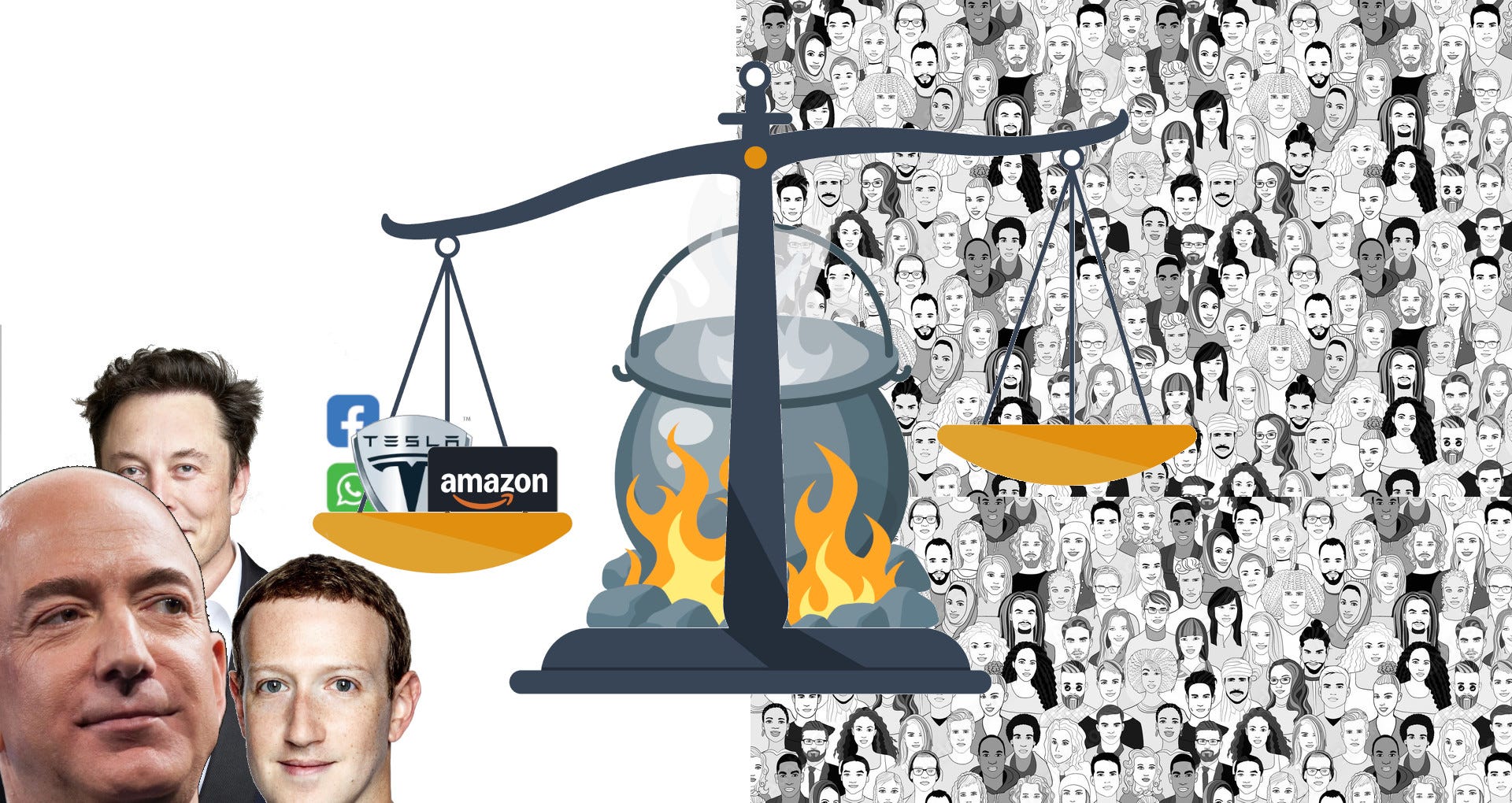

Indeed, this is what evangelists for billionaires will always claim: the reason he’s a billionaire is that he contributes so much to the collective soup. In essence, they imagine a vast set of scales, with people like Musk and Bezos contributing an enormous amount of ingredients, brilliance and labour, with this contribution being recorded as positive money credits in their account, which they can rightfully take back to the rest of society in order to demand vast goods and services back from us - in essence, claiming huge quantities of the collective soup.

This story sounds superficially plausible, doesn’t it? Their enormous bank balances must surely mean they’ve contributed enormously, and surely that means they deserve to consume enormously? Ah, but there’s a catch. We live under capitalism.

Financing stone soup in the capitalist ecosystem

What we call ‘capitalism’ introduces a little glitch to the reciprocity matrix, but understanding it requires a couple conceptual building blocks. Firstly, remember that, at a primordial level, an economy is a group of people coming together to survive. Secondly, any economy is always limited by how many people there are and how much stuff, or assets, there are to work with.

In a large-scale market economy like ours, which has specialised divisions of labour and property ownership regimes, certain ecosystem-like qualities emerge. Here are three of them

There are only limited slots for particular roles. If everyone tried to be Bezos, what would happen? Well, Bezos makes decisions and tells other people what to do, so if everyone was him, you’d just have billions of people trying to tell billions of other people what to do. That would just cancel itself out, with everyone standing around shouting at each other. Much like a natural ecosystem only so many spaces for apex predators, an economic system like ours has systemic limits on how many large-scale directors there can be

We only need so much of certain things, but those things require other things. Our specialist roles fall under ‘industries’, but all of these are interlinked. If everyone tried to start making jumbo jets there would not only be a massive oversupply of useless jets that won’t get used, but all the components for the jets that come from other industries would fail to materialize - i.e. if everyone is making jets, nobody is making steel for jets

There’s a finite number of productive assets in the world, and finite ways to own them. What we call ‘productive assets’ are things used to make jumbo jets and so on, and there are two possible extremes in terms of how they are owned. At one extreme there are large numbers of us owning small amounts of the assets equally. At the other extreme there are small numbers of us owning large amounts of the assets unequally. So, there are systemic limits to how many large-scale owners of assets there can be

If there are any forces in your system that allow for gradual concentration of ownership, your system will move towards that latter situation. You can read more about how that happens here, but the net result of these factors is: we have finite numbers of leadership roles in finite numbers of industries with finite potential for expansion and finite numbers of ownable assets used in the process, and we have moved to a situation in which certain people in leadership roles in each industry also own the most.

Those people are the big Stone Soupers, and the not-so-secret secret to becoming like them is to own large amounts of shares in productive assets (e.g. the pot) that others require to make the collective soup. If you can do this, you can get extraordinarily wealthy, because you control an underlying infrastructure - or ‘means of production’ - that everyone else in the interdependent system is using to survive.

There are various ways to get into this position. Outright violent expropriation was a classic of the early capitalist era, but one of the biggest ways to do it nowadays involves having access to money from the financial sector.

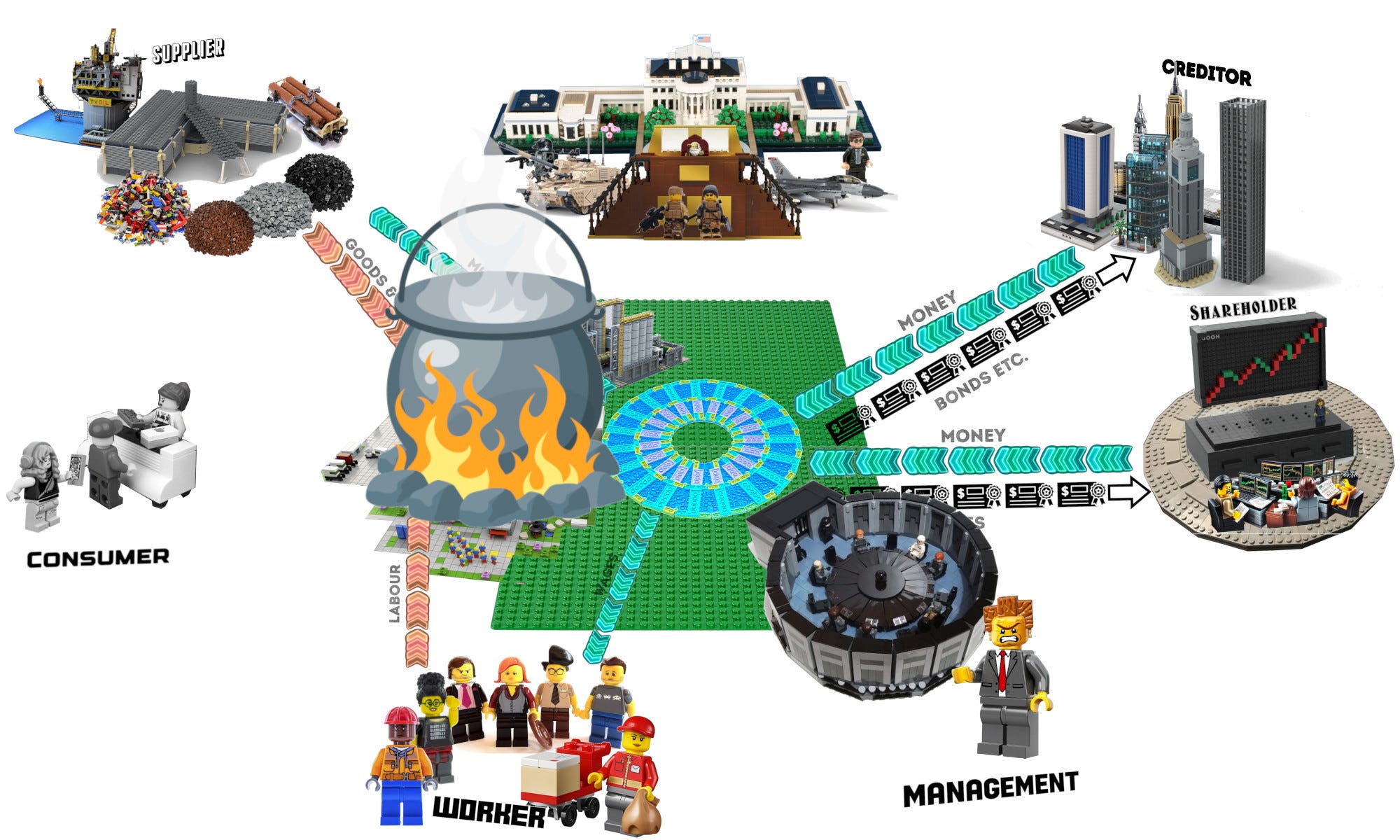

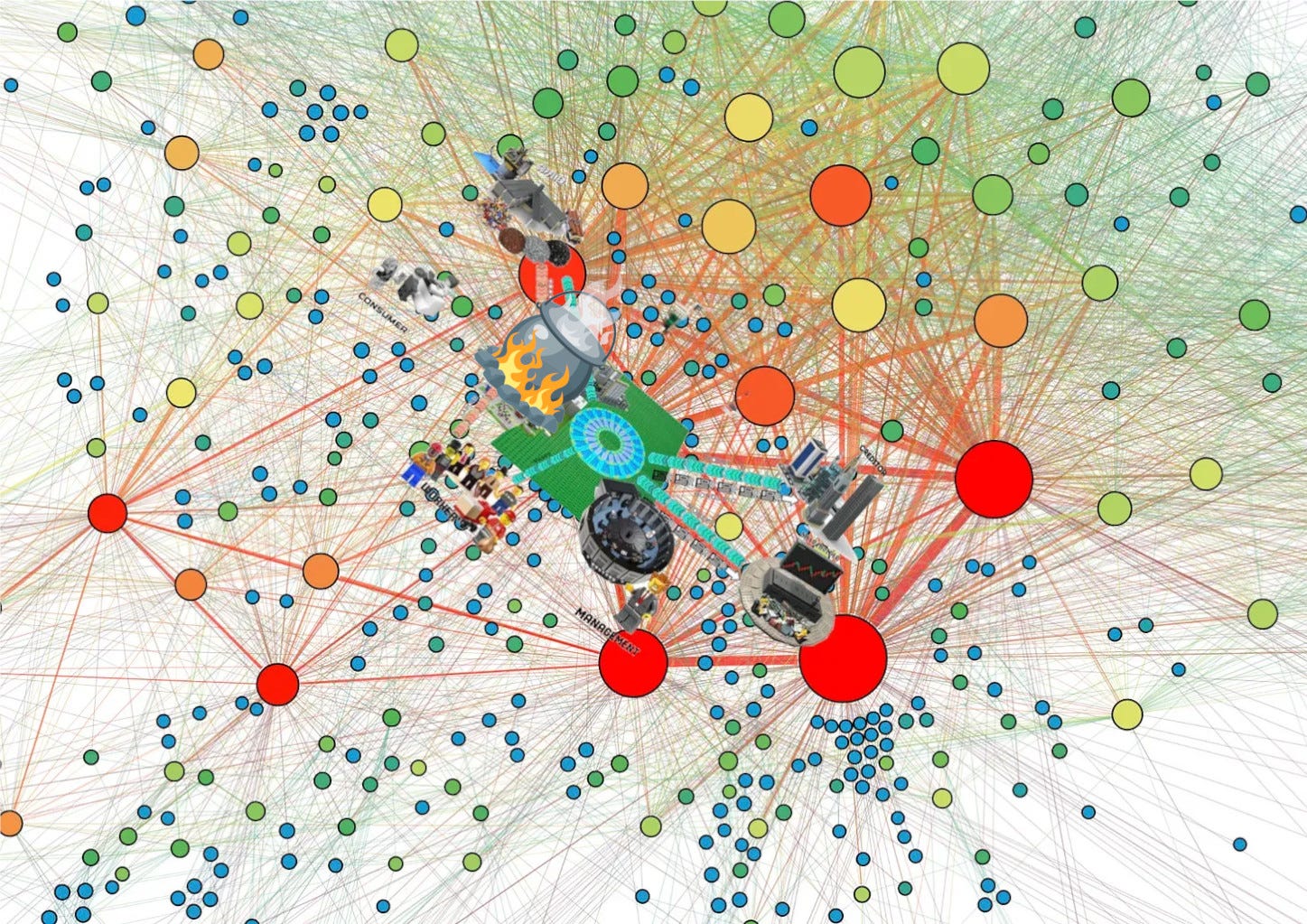

Here’s how that works. The financial sector operates alongside Stone Soupers, and other senior managers of firms, to raise money. That money is used to mobilise workers and suppliers to produce things. The end result is pushed out to consumers. The surplus money goes back to the instigators (see my Lego Model of Corporate Capitalism).

If you want to render this in Stone Soup form, here’s how it looks.

Access to finance is what enables big Stone Soupers to get workers to ‘put something into the pot’. To understand this, you need to recognise the crucial distinction between:

Soup ingredients - which are represented above with the orange lines that says ‘labour’ and ‘goods and services’

Rights to claim soup, which are represented with those green lines that say money

This is conceptually tricky for many people, because we’ve often internalised dodgy mainstream economic understandings of money, in which money is spoken of as a kind of substance - or soup-in-itself. You need to deprogram yourself from this belief.

Let’s alter the original parable to try make this slightly clearer: Imagine that the stone-souper hands out vouchers to eat soup to anyone who sources the ingredients and chucks them in. That’s kinda what managers are doing when they pay workers to produce stuff that workers will later buy and consume. After all, who are the ‘consumers’ in the image above? Well, a significant chunk of them are people who earn income by working. At a meta-level, they are buying the soup they were paid to produce, cashing in their vouchers to eat it.

To see the full picture of this we need to zoom out from the single corporation, which is but one slice of a colossal web of relations that makes up a much larger economic structure.

We’re used to imagining separate ‘companies’ as discrete entities, but every corporation is tied to many other corporate structures, each of which has its own ‘pot’ of stone soup. In reality, a corporation is a subsystem within a much larger system, and even these subsystems have subsystems within them.

For example, Amazon.com is an e-commerce business, but it’s also a provider of datacentre hosting. That’s actually just two companies glommed into one, and there’s no reason why we can’t - at a conceptual level - just glom all companies together and imagine them as one giant meta-company. In fact, we have a name for that meta-company. It’s called The Economy.

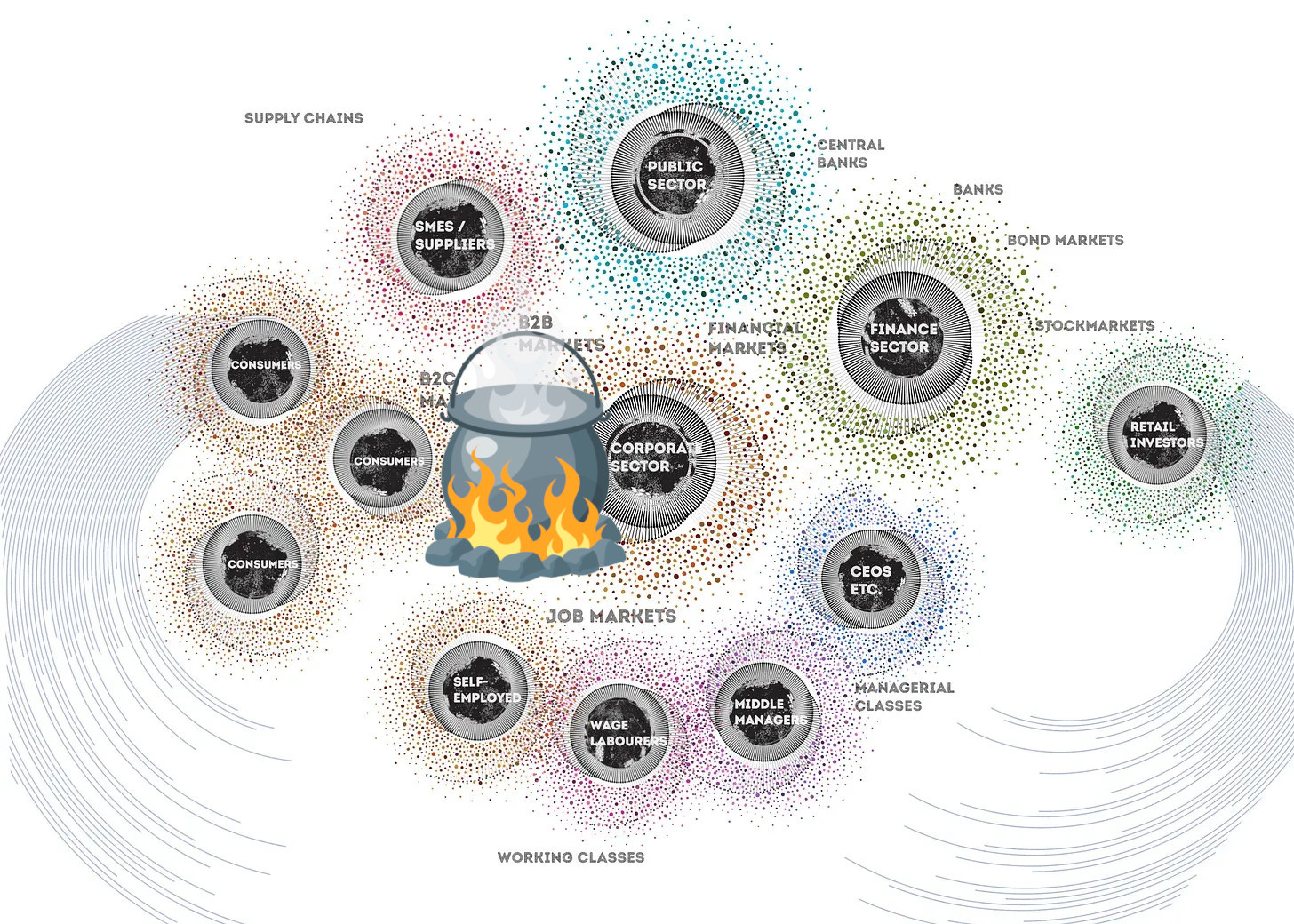

If we were to take every single company like this, and meld every one of their stone soup pots together into a single mega-pot, we’d see the entire world rendered in classes of people. There’s the shareholder class, the creditor class, the various subsections of the working class and managerial class. In the end, all those classes are also consumers - the ones who will eventually eat the collective soup that everyone produces. Let’s visualise these groups somewhat like this…

What really matters in this overall picture are questions like who owns the pot, who calls the shots, who provides the ingredients, and who gets to consume the outcome?

Remember that ‘consumers’ are just people using their ‘vouchers’ - gained either as a worker or as a manager or financier - to claim the soup. What happens in our system, though, is that corporate structures create very specific relations of production, in which one class of people - who collectively own the pot - essentially gets paid rent by workers who operate it in order to survive.

This rent isn’t a literal payment from workers. Rather, it’s in the form of the differential between how much workers get paid to produce everything in total, and how much it gets sold for to everyone in total. If you want to put this back into ‘soup voucher’ terms, it’s the difference between vouchers given to workers to produce soup, and how many total vouchers there are.

In some geeky circles, this is known as the difference between returns to labour and returns to capital, but one thing you can be sure of is that our collective output - the soup that society makes - always comes along with the message that it’s provided courtesy of big daddy Bezos, Musk, Zuck, Trump, or whoever. That’s ideologically how they end up justifying why they get to claim so much, but is this really a fair distribution?

Jobs create billionaires

We’ve already seen that apologists for extreme wealth try to claim that billionaires do lots more than everyone else, but this is empirically incorrect. Billionaires are finite beings like anyone else, and they can only do finite things. A fall-back position, though, is to claim that the billionaires, alongside the financial sector, ‘create jobs’ for everyone else - in other words, they give everyone a role and direction.

In a technical sense this is true, just like the Stone Souper in the village square ‘creates jobs’ for the villagers who go off to get the vegetables. But those jobs are not like charity handed out to the poor villagers. No, the villagers are doing the work that results not only in the soup, but also in the adulation and enrichment of the instigator.

Put differently, if you’re going to accept the line that billionaires 'create jobs for workers', then you must also accept its mirror image, which is that workers create billionaires. Jeff Bezos hasn't delivered a single package in his life. Without the deliverers Amazon.com is but a fantasy in his head.

Consider what happens if the Stone Souper just stands there with no villagers. All he has is a pot with stones in it. Similarly, consider what happens to Amazon’s income if all those delivery people and warehouse workers don’t turn up to work for two weeks. You just have the management team standing around twiddling their thumbs, hoping that the packages arrange and deliver themselves. That’s obviously not going to happen, so a strike like that has a massive impact on the company. Now consider what happens to the company if Bezos goes on strike for two weeks. Nothing. Everything keeps going.

So, how is it that Bezos will earn $26 million a day regardless of whether he turns up? Well, he owns the shares, which is like controlling the pot that others cook in. It’s physically impossible for a single person to do actual labour that would earn $26 million per day through a salary. A major percentage of billionaire wealth is just rent scraped from workers via share ownership structures.

This is how we end up with this class of chronic stone soupers - the 1% - who control wealth far beyond any natural contribution to society. Going back to our scales of reciprocity then, in which you get back what you put in, are there still ways to argue that billionaires ‘deserve’ what they’re getting back? Well, let’s close by looking at two last arguments.

The Great Men take risk, and uplift everyone else, right?

One classic argument is that big owners of capital absorb risk for everyone else. After all, as a shareholder in a company, your payout can wildly fluctuate, while as a worker it stays fixed. Perhaps big shareholders are doing workers a favour, shielding them from the chaos of the market and taking a bigger cut in return.

This idea that the collective owners of our collective productive assets take risk - and do us a favour by merely getting us to operate those assets for a fixed reward - is an old idea, but it largely operates as an after-the-fact argument. After all, what risk was ever taken in the early stages by the Stone Soupers? In reality, someone like Zuckerberg was just a college student who gradually got people to build out his idea while he retained share ownership. Was that more risky, than, for example, being a migrant labourer from West Africa who spends all their small savings to cross stormy seas to find wage labour in France?

In fact, true success under capitalism isn’t about hard work and simple just desserts. It’s about leveraging power to accumulate productive assets that will draw more power to you over time. Actually, looking at the Zuck example, we can alter the parable. His early seed investors enabled him to hand out vouchers to workers to build the goddamn pot, never mind the soup, which he could then use to attract others. Now he finds himself at the helm of a giant asset built by countless unnamed engineers and grad students.

While it’s true that the assets owned by Zuck are subject to uncertainty - aka. the broader public might lose interest in this particular batch of soup from this particular pot - on average, the rewards of share ownership are far in excess of any risk absorption service Zuck ever offered to his workers.

I’m happy to give credit to Stone Soupers for their initial vision, their drive, their instigator role, their willingness to act as a focal point, and - to a small extent - some risk they take on, but none of this truly accounts for how much they get paid. After all, they’d get nothing if other people didn’t do the work.

But this leads us to the final line of defence for billionaire-worshippers, who say without the inspired leader, nobody would do the work. Without the billionaire, everyone else would just stand around useless, slowly starving for lack of coordination, leadership, creativity and vision. This belief lies at the core of Ayn Rand’s philosophy. In her novel, Atlas Shrugged, this is represented by the character of John Galt, a lone heroic inventor who - feeling under-appreciated - organizes a strike of all the creative entrepreneurs, supposedly leaving all the ungrateful normies to wallow in mediocrity.

This returns us to our Great Man Theory, but Great Man Theory is a load of crap. No person stands alone in production, whether that be in the production of goods or ideas. Not only would Bezos’s neurons not fire unless workers in Guatemala gave him his coffee, but he’d never have thought of Amazon.com if tens of millions of other humans throughout history had not thought of every other innovation that leads up to the Internet. Furthermore, none of those people would have thought anything at all if they weren’t birthed, cared for and fed by mothers, and those mothers wouldn’t have done that if many others hadn’t gone out and found food, and that food wouldn’t exist if it were not for the sun doing most of the work. In reality, Amazon.com originates in the sun - not in Jeff Bezos - but the sun isn’t claiming anything.

This belief that ideas literally originate in a single person’s mind, and that they should be paid by the rest of humanity for the rest of time is fucking ridiculous. Ideas do not reside inside self-contained people - they reside in a network of interdependent and interconnected people - but the fact that Bezos, or Musk, or whoever, was an early-mover in articulating a particular idea means they get locked in as somewhat arbitrary figureheads, and the fact that they’re billionaires simply reflects the legal reality of share ownership. They are products of our system, not creators of our system. If they didn’t exist, others would take their place.

So, when someone says something like ‘without Bezos we wouldn’t have Amazon’, it’s much like someone saying ‘without John at the party last night we wouldn’t have had that conga-line’. Maybe so, but you might have had Judith starting a breakdancing session instead.

In the final analysis, we can agree that neither John nor Judith will make any dance formation happen without others. Ayn Rand may believe that we’d all be lost if we didn’t have John, but Galt would also be lost without the rest of the world. He’d be walking around with his stones banging in his battered old cauldron. The inventor does contribute, of course, but they contribute as part of an ongoing collective that stretches back 200,000 years.

This applies to everyone. In fact, it even applies to this argument I’m making. Imagine if I, Brett Scott, claimed that every idea, concept, and word that is arranged here, uniquely emerged from me, without assistance from tens of thousands of years of human language and concept formation, developed organically by millions of people of all genders who’ll never be recognised as ‘Great Men’. It may be the case that I, like Bezos, introduce some new angles on old themes, around which new formations might emerge, but with us alone they’re just fragments of stone.

Love it. This segment "It’s about leveraging power to accumulate productive assets that" I find is particularly underestimated in terms of there having been many if not actually better pots than e.g. Zuckerbergs, but the bully seed funders and Zucki ensured other pots were absorbed or never saw the light of day making it almost retrospectively appear as if the winning pot naturally succeeded.

Very nice article. Deep and helpful.

And…. In a way, doesn’t it all stem from the vision others can create in our brains? From stone soup to walking on Mars? It’s that certain people have the ability (definitely exploit) to create that vision in others’ minds. Without wisdom and responsibility guiding those visions (in both parties), we’re left with what you describe.

I’ll not debating any of what you wrote. Great examples and wonderfully helpful. Trying to digest for myself why this continues as means of controlling people’s behavior when they/we KNOW better.