The Accelerationist Playbook

How illusory races towards high scores lead us to corporate domination

Paying subscribers can access the audio edition here (14 minutes)

Tech isn’t a relaxant. It’s an accelerant. Automation technologies, whether they take the form of AI, digital payments or Uber, primarily make our lives faster, rather than easier, but we’re flooded with stories that present this acceleration as unstoppable progress. To survive this propaganda without losing our bearings, we need to start studying the tech accelerationist playbook, the stories and background mental models used by mainstream progress junkies to sell their techno-utopian visions. In this piece, I’ll show you four core moves made by garden-variety tech optimists, and two techniques to disrupt them.

Move 1: They use the high score model of history

In a typical video game, a player starts with a score of zero and then accumulates a higher score as they move up levels. They also build an inventory of items, and constantly upgrade that inventory as they reach higher levels and scores.

Mainstream stories about technological progress are based on the same framework. We start with a background image of humans as prehistoric beings with a score of zero, and then proceed to describe history as a long march in which we go up levels, moving in a general trajectory towards every higher technology, speed, accumulation, complexity and scale.

Within a high score ideology like this, innovations (such as the aforementioned AI, smartphone apps or digital money) are seen as moving us to a new ‘level’. Not only are they perceived as increasing our score and capacity, but they’re seen as upgrading a previous inventory. Through this lens, something like physical cash belongs to an older inventory, so must inevitably be discarded.

There are two crucial features of this worldview to be aware of. Firstly, in a video game, you always retain your score as you go up levels. You never reset, or rebase, to zero as you start a new level. Similarly, high score visions of history assume that human society carries over all the gains - or ‘points’ - it picks up over time.

Secondly, a character in a video game only has a single track and single score, and a single throughline that connects the beginning of the game to the end. Likewise, high score history has a sense of a singular path from the past to the future, rather than simultaneous parallel paths.

Move 2: They cast the single path as a ‘race’

When looked at from the perspective of the present, the singular path of increasing score going into the future is imagined as a race. For example, it’s extremely common for business journalists, conferences, innovation pundits, think-tanks and political leaders to talk about a ‘race to cashlessness’.

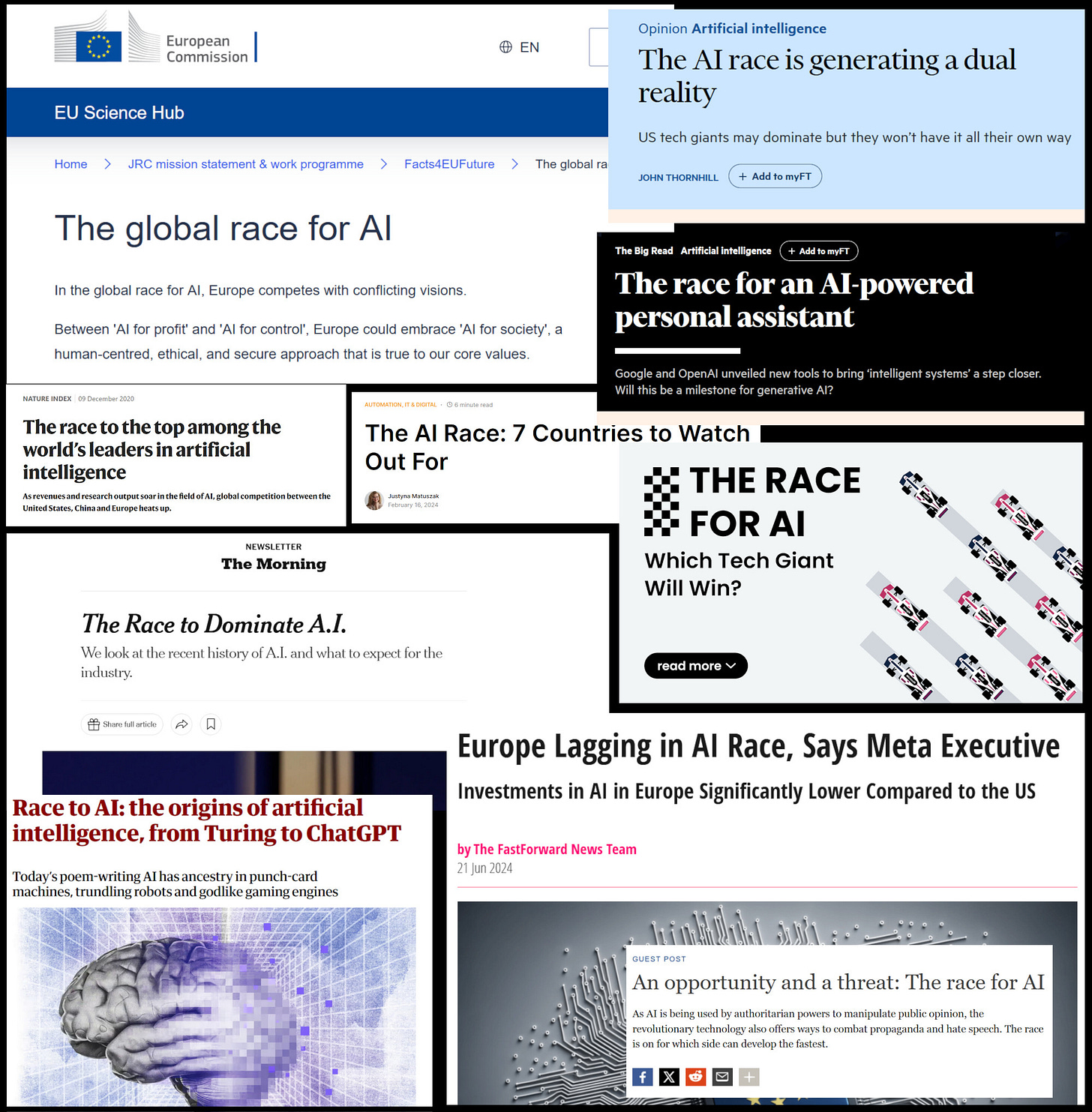

This isn’t unique to the payments sector. It applies everywhere that an automation process is occurring. For example, there’s supposedly a ‘race to AI’ occurring.

Racing metaphors naturally create imagery of those who lead, follow, and lag, and so break down into three sub-narratives, each starring a particular group:

The Leaders: the digital tech industry is imagined out in front, ‘leading the way’ towards this future. Tech magazines run stories about inspiring, trailblazing and heroic entrepreneurs daring to do this, funded by visionary VCs

The Followers: society more broadly is imagined as muddling along in the middle of the race. The small business section of a general newspaper might run stories about the need for readers to ‘keep up’ with new trends. This follow-the-leader mentality is reinforced by politicians, who position themselves on the proverbial sidelines, encouraging us to stay up-to-speed with the transition

The Laggards: If you’re not leading the way, and not keeping up, then you’re languishing at the back of the race. In the case of AI, this turns up in the form of stories about future technological unemployment, or the poor sods who may be outcompeted after failing to adopt it. Similarly, in the case of digital payments we see a spate of stories about those who may be left behind.

This messaging is also found in the political realm. For example, the UK Labour politician Alex Davies-Jones writes: “While the trends seem to suggest that we are moving towards a more cashless society, it is really important that we make sure we do this in a managed, careful way, making sure that nobody is left behind”. The title of her article is ‘Access to cash is still crucial’. Notice that word ‘still’. It generates the idea of a temporary situation. She’s not challenging the idea of the Race. Rather, her plea is to slow it down slightly, to give people time to ‘catch up’.

Move 3: They use the race to generate a salvation story

If we agree that people are at risk of being left behind, then it must follow that they need rescuing. Those at the front of the imagined race are often the loudest in promoting this rescue. In the payments sector, this takes the form of VISA, Mastercard and fintech firms presenting themselves as eager to help through ‘digital financial inclusion’ programmes.

For these firms, ‘inclusion’ simply means onboarding new customers and increasing profits, but the sector is ideologically primed to view its own interests as being in the interests of society more broadly. After all, they imagine themselves to be leading the way into the future, and thereby perceive a responsibility to bring everyone along with them.

This progress narrative, and the inexorable feeling that accompanies it, becomes entrenched as a paradigm. A paradigm is a subterranean framework for thinking, so deep that it goes unnoticed, which governs what questions are considered valid to be asked about any particular issue. So, rather than reflecting seriously on the question of whether people might reject the direction of travel, reject the race or reject the vision of the destination, well-meaning research communities will channel the paradigm through questions like ‘how can we enable an inclusive digital transition?’

This is how even well-meaning social workers with no commercial interest in digitization can become champions for large financial and technology companies. For example, a whole range of civil society groups and NGOs have joined the Better than Cash Alliance, which describes itself as a “partnership of governments, companies, and international organizations that accelerates the transition from cash to responsible digital payments to advance the Sustainable Development Goals”. The Alliance is hosted within the UN Capital Development Fund, and was funded by VISA, among others. Here’s the Visa press release about this in 2012:

Move 4: They cast anxiety as a conservative reaction

The mainstream story coming out of tech startups, the corporate sector and government is that we should all experience a desire for these ‘transitions’, but many people feel anxious and threatened by them instead. Within a high score vision of history, this anxiety will be cast as conservative, in the small-c sense of being frightened of change, and refusing to progress to a new ‘level’.

This creates inner conflict in those anxious people, because they’ve often also absorbed the race narrative by osmosis, sensing that new tech is ‘coming’ whether they like it or not. When their anxiety collides with this sense of impending inevitability, they’ll start to feel like an old horse-cart driver shaking their fists at passing cars. This also makes them vulnerable to the so-called ‘populist right’, because one strategy used by the latter is to prey upon fear of looming digital overlords, and to channel that valid anxiety through simplistic conspiracy stories that get laughed at in mainstream circles.

Populist movements not only feed on fear, but will attach it to nostalgia, encouraging a person to imagine themselves as part of a movement, like an uprising of horse-cart drivers facing off against the auto industry. Perversely, this strengthens the apparently ‘progressive’ credentials of the tech accelerationists. After all, if you’re against them, you must be with the crazies. This is how liberal urban professionals might end up seeing the Better than Cash Alliance, or corporate behemoths like PayPal, as representing progressive values rather than capitalistic power grabs.

Breaking the chains of digital ideology

There are many more moves in the tech accelerationist playbook (see my Big Techtonic and Cashback series for more), but let’s start deconstructing the ones we have. A good starting point is to reject two assumptions found within the standard high score vision:

The first is that idea that we retain high scores. Learning to deconstruct this takes practice, but here’s the short version: in actual human society, we not only psychologically and culturally adapt to changes, thereby neutralizing them, but we also recalibrate the entire economy to incorporate the new things as new baseline inputs to survival. Put differently, we only start to ‘need’ the new things after they’ve been introduced, and once this happens, the removal of those things takes you negative, because we’ve moved the ‘zero line’ upwards. To understand this rebasing process, check out my piece Money as Addiction. Interested readers might also see my recent If Everyone was a Billionaire, which hints at this zero line from a slightly different angle.

The second assumption is that there’s a single track into the future, rather than parallel tracks. In a standard high score ideology, older things are always lower and being left behind in the rear-view mirror, but in a parallel track world they can coexist simultaneously, like things moving in different lanes.

The easiest way to grasp this is through the examples of bicycles and stairs. Is it reactionary to call for bicycle lanes in a world dominated by cars? No, that’s considered progressive. Is it outrageous that we ‘still’ use stairs? No, that’s entirely normal, and important.

Bicycles and stairs don’t merely represent older ways of being. They’re parallel ways of being that draw upon a different concept of progress, one of diversity, balance, autonomy and resilience, rather than acceleration and expansion. In this sense, they’re just as modern as escalators and Uber. In fact, a world in which we were only able to use the latter would be a nightmare. We want balanced systems, rather than narrowly ‘efficient’ or ‘convenient’ ones.

From the parallel track perspective, the ‘upgrade’ or ‘level up’ viewpoint starts to crumble. Nobody is going around running research projects into how to help us all make the ‘transition’ from cycling to Uber, and there’s no ‘Better than Bicycles Alliance’ (in fact, if there was it would be seen as an obvious front for industry).

So, what happens when we take things demonized within the single track vision of history, and recast them in a parallel track world? What if we called cash the bicycle of payments, and ApplePay the Uber? What if we called writing an essay that comes from your own mind with a pen the bicycle of thought, and the generative AI one as the Uber of thought?

Well, the first consequence is that the imagined polarity between progressive and reactionary inverts. The conservatism switches to the digital accelerationist side, because the true thing that’s being held onto in the mainstream is digital progress ideology, the unchanging idea that the only thing that human society should optimize for is ever increasing speed, automation and corporate intermediation. From a parallel track perspective, digital ideology is a form of economic conservatism that favours a concentration of power into particular industries - Big Tech, Big Finance, and so on.

Secondly, the paradigm shift rearranges what research questions are considered to be valid. Rather than asking ‘how will we help people adapt to the digital transition’, we might ask ‘how can we keep a good balance of power between parallel tracks’. Asking that question is a good step towards true progress.

Outstanding as ever, Brett. And I'm strongly reminded of this from the late David Fleming's Dictionary for the Future and How to Survive It!

-

"Here is the villainy of distraction revealed by the simplest of all possible subjects for debate: the proposition that two and two makes four.

Distraction might urge, for instance, that the idea is old-fashioned, that the time has come to move on from traditional thinking on the matter, or that it is too technical for the public to understand. It could take the form of an ingratiating assurance that the only thing that matters, naturally, is the well-being and happiness of everyone concerned. Distraction might urge that it is perfectly okay nowadays to think that two plus two makes five; or that even thinking about it means an unforgivable neglect of the far more important proposition that three plus four makes seven. You might be invited to take note that there is money to be made by taking a different view of the matter, or that we have to move on from the notion if we are to be competitive, or that the proposition is a bit rich coming from someone with a private life like yours. Or it could insist with some passion that, contrary to the view that two plus two makes four, we must take our place at the heart of Europe. Distraction might add, with hoped-for finality, that the argument has already been lost: two plus two is going to make five in the future, whatever we do...

Distraction, evidently, has the power and freedom to cause havoc wherever it likes. It is a spoiler, worse than the cheat: the cheat at least recognises the existence of the rules on which argument depends if it is to make any sense, even though he then proceeds to break them, hoping not to be found out. Distraction recognises nothing except conquest: the argument is too serious to have any connection with the orderly rules of honourable play; it will be settled by other means. Rules? What rules? It presumes the death of logic.

A characteristic form of distraction is to make an assertion which is not true, but which is hard to disagree with. This happens, for instance, with the appeal to the inevitable: the distracter does not argue for or against a proposal; instead, he simply asserts that it is going to happen anyway, and he may do so in a slightly bored drawl that passes off the sell-out as if it were a routine comment on the weather.

Don’t stand for this: it is one of the ways in which our citizen’s right to have a say in deciding for ourselves dwindles into a loss of belief that we can influence anything at all. It is designed to induce give-up-itis, an acceptance that technology and the sweep of history make the decisions. What we are then supposed to do is to surrender, to make sure we are not in the way."

(Source: leanlogic.online/Distraction )

Overall this is a great post. One nit to pick: referring to "they" as nefarious forces, when usually they're just low-paid journalists trying to their job, is right out of the populist playbook. I don't have a generalizable alternative answer to it, just something to be aware.