Paid Subscribers can access the audio version here

I can’t pinpoint the exact moment I became a smoker, because it was a gradual slide from voluntary once-off puffs to involuntary addiction.

It began when I was working in the financial sector during the 2008 financial crisis. Many of my fellow brokers smoked, and the drags started here and there after work as a way to connect with colleagues, and as a means to get a short-term buzz. Those single hits of nicotine accumulated and set off a shift in me, a slippage that became a landslide. My resistance to dependence eroded, then collapsed. I was in. I was addicted.

I was locked into this state of capture for eight years. I’d start the morning with a cigarette and then punctuate every point of transition in the day with one - waiting for the bus, getting out the train, getting up for a coffee break, walking to lunch, walking back from lunch, having drinks - until finally ending the day with one. I could handle a smoke-free period of about 1.5 hours, but much longer than that was a struggle. Long distance flights were tough. My longest break was two days, when I found myself stranded on a US military base without cigarettes or a shop. It was hellish. I remember escaping on the third day and running in a semi-crazed state for half an hour to get to a Californian suburb where I found salvation in a gas station that sold American Spirit tobacco. I would have eaten that out the package if I had to.

Addiction inverts our concepts of agency. We like to think there’s some external purpose to stuff we do, and that we direct ourselves towards that purpose, but when we’re addicted those (already somewhat dubious) notions don’t apply. It would be ridiculous to ask why a smoker ‘chooses’ to smoke. As I ripped open that American Spirit I wasn’t choosing anything. I was trying to escape the terrible withdrawal symptoms that were wracking my body, the result of my chemistry having being altered by cigarettes. That was animal instinct, not rational choice.

So what’s this got to with monetary systems? There’s a self-perpetuating circularity at the deep core of addiction, and this is what I think about every time I see economists talking about why we use money, and it’s supposed ‘functions’. I see them presenting a state of involuntary dependence as a state of voluntary choice. Let me explain.

The problem of solutionism

Before addiction, you’re a different person with a different body. If you have a non-addicted body there’s a voluntary element to smoking, and you might even imagine the cigarette as having some external function: I smoke to do X, Y or Z in the world. You could present it as being a ‘solution’ to some problem: boredom, social anxiety, or tiredness, for example.

As the cigarettes slowly change your body, however, you’re being rebuilt, transformed into a different person. You become a creature created by the cigarette, and once this happens smoking not only ceases to be voluntary but also ceases to have an external function. Once addicted, you’re not smoking to get something good out there in the world. You’re smoking to avoid something bad inside yourself: the breakdown of your new body, with all the tremors, sweats and anxieties that it brings. In essence, you’ve created a new form of ‘hunger’ inside yourself, and it must be satisfied. In this situation, the true function of smoking is to avoid the pain of not smoking.

So, if I was tasked with creating a narrative about why smokers smoke, it would be simple: they smoke because they’re addicted. The problem the cigarette is solving is the problem of life without cigarettes in a body that’s become dependent on them.

In many other areas of life, however, we hear elaborate stories about the external functions of things we’re dependent on, which supposedly justify why we use them. Kids going to museums, for example, might get told about the purpose of agriculture, or ‘why money was invented’, or how electricity solved X or Y problem. They’re encouraged to imagine a worse-off world before these solutions, and a better-off world after.

This belief that innovations have particular positive purposes or functions that inspire their invention (and that explain their continued use) is particularly strong in entrepreneurial culture. In Silicon Valley, for example, startup founders justify everything they do with reference to some imagined problem they’re solving. This outlook is called solutionism. Through a solutionist lens, the world is a series of problems that gradually get solved, like cracking puzzles in a video game to unlock a new level where more advanced puzzles have to worked out, until you eventually win the game.

Progress as a high score

The key to understanding solutionism is to recognize that it’s built upon the assumption of a stable and absolute base against which progress is measured. In a video game you start at Level 1 with a score of 0, and then progress upwards (or forwards), accumulating a positive score against this fixed zero-point backdrop. The characters in these games often also build up an inventory of useful things that give them ever-greater powers, which expand along with points and levels. As you get to a new level, you don’t reset or ‘rebase’ to 0. You carry over the points and move onwards towards a new high score.

This is how solutionists picture society. They imagine a proverbial ‘Level 1’ world of prehistoric people who gradually solve things through acts of discovery - fire, agriculture, writing, and so on. This sets society on a path ‘upwards’ or ‘forwards’ to new levels. History is us accumulating an inventory that expands our capacities.

Crucially, we are seen to be externally augmented but internally unchanged by this growing inventory. It only adds to our lives, and never fundamentally changes us or the requirements for our survival. The solutionist mental model rejects the idea that we ‘rebase’, and this is why it’s so flawed.

Rebasing

In our interdependent economies, the expansion of capacities is mirrored by the expansion of needs, along with the altering of skills, culture and expectations through adaptation. We’re trained to notice that the proverbial caveman has less stuff and lower technological capacity, but we fail to notice that they also need less stuff, have less dependence (i.e. they have more internal resilience) and don’t care in the slightest about our judgement of their lives.

Here’s a simple example: early societies could survive without going to a supermarket, while we can’t. If a supermarket were miraculously dropped into the inventory of our prehistoric man above, it’s true that it would give him a big ‘positive score’, but - over the span of decades and centuries - that would sink back into the background as the new baseline for survival. In modern-day society, a supermarket doesn’t earn positive points. Rather, if it were suddenly removed from our inventory, we’d go negative: we’d be dying in the streets with no means to make or find our own food. We’d be flooding out into the countryside in a desperate attempt to relearn agriculture in a week.

So, having a supermarket in our inventory simply takes us to zero on Level 1, while the cataclysmic consequences of not having it are not experienced by our ancestors. That’s because they have a different zero point. The imagined stable and absolute base against which to measure progress is an illusion.

So how does this relate to monetary systems? Well, if you look at standard economics accounts of money, they inevitably start with some solutionist story about how money was invented to solve some problem that humankind experienced, and how it continues to solve this problem for us. They also imagine that if we stopped using money, we’d lose our high score, sliding backwards down the levels towards zero. This is because solutionism imagines that we retain the gains of a solution, rather than adapting and rebasing.

Note: This piece is a supplement to my Intro to Economic Life course. Do sign up for that if you’d like to go deeper.

Dissolving solutionist accounts of money

Cigarettes turn out to be very useful in illustrating the flaws of solutionism, and in providing an alternative lens through which to view history. Smoking doesn’t ‘solve’ a preexisting problem to get me to a higher level. Rather, it just changes the conditions of my Level 1. It dissolves one state of being and replaces it with a new one in which I go negative if I’m not smoking.

This is a provocative frame for thinking about monetary systems. To escape solutionist accounts, you have to accept the possibility that money was introduced into a world where there was no intrinsic or systemic ‘demand’ for it (much like my body has no demand for cigarettes in a world where I’ve never encountered them). From this perspective, the history of money is a series of political-economic events where people who didn’t rely on money slowly took little puffs on it in limited situations - the monetary equivalent of ‘social smoking’ - or were forced into it through acts of political coercion. This sets off a shift, then a slippage that becomes a landslide. Resistance to dependence on money erodes, then collapses, locking the society in.

As any economic anthropologist knows, there are many ways that pre-capitalist societies collaborated for survival, using combinations of logics and practices that ranged from informal reciprocity, gift-exchange systems, hierarchal redistribution, patronage systems, and small-scale communism alongside forms of commercial exchange. As I discuss in my video and article on Tabu ‘shell money’ in Papua New Guinea, many pre-capitalist ‘currencies’ were not commercial in nature, and were only used in ritualistic settings to mediate social relations and power.

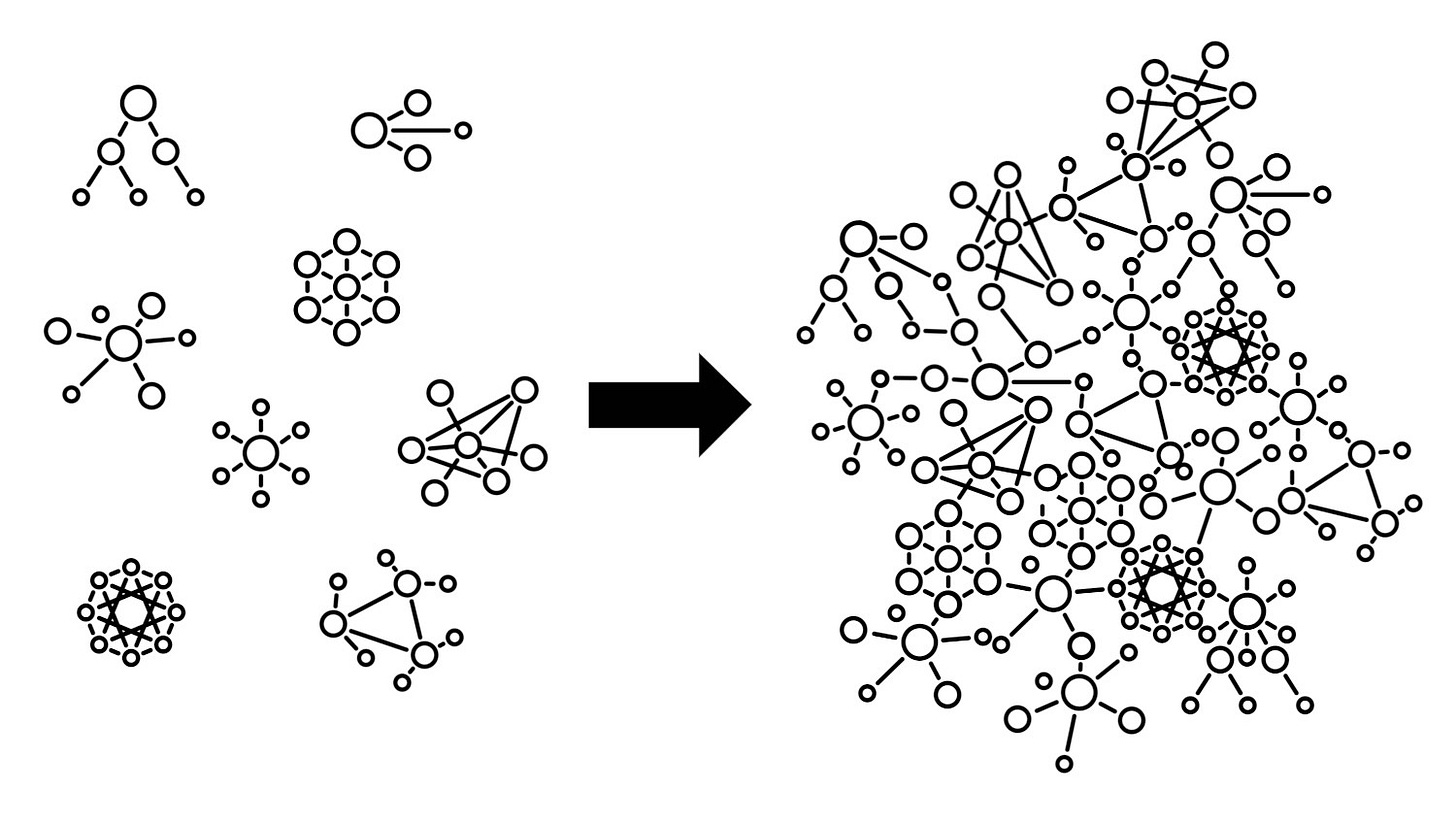

The capitalist money that we’re used to, however, is inherently linked to the rise of states, imperialism and colonial conquest. This is not the place to recount that history, but - in highly stylized terms - political actors introduce credit systems, forms of coinage, and tribute systems that gradually snowball into larger systems. Money acts as a dissolution agent, dissolving situations of small-scale interdependence and recombining them into large-scale interdependence. It transforms smaller discrete economies into larger integrated ones.

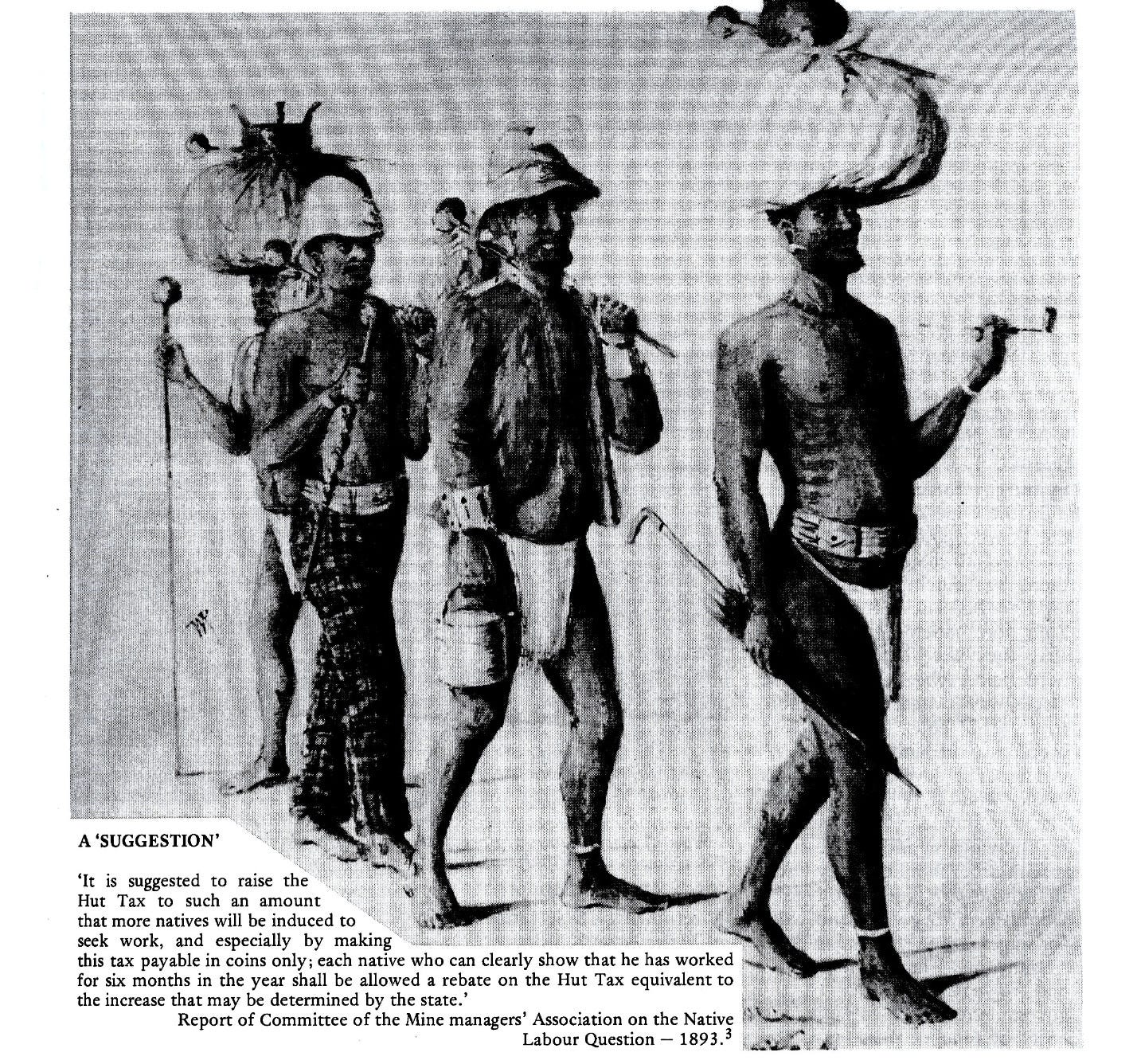

For the groups on the left of the picture above, money might once have had some optional element to it. For example, in my homeland of South Africa in the 1800s, Zulu, Xhosa and other groups held onto traditional subsistence systems that enabled them to live outside the colonial market economy, while occasionally dabbling in those markets. This slowly changed, however, as the colonial government forced them to pay ‘hut taxes’ that required them to work in mines to get the colonial money needed to pay the tax. This is spelled out in the 1893 report about the ‘native labour question’ by the Committee of the Mine Managers Association: “It is suggested to raise the Hut Tax to such an amount that more natives will be induced to seek work, and especially by making this tax payable in coins only”.

The word ‘induced’ is telling. It suggests a process of trying to artificially stimulate demand for something that isn’t intrinsically demanded. This is the early stage of proletarianization, the process by which people are severed from a previous means of survival and integrated into a new one - wage labour.

As monetary exchange spreads, it changes the structure of our relationships and removes us from those old scenarios where it was not necessary. It changes the ‘chemistry’ of our economic body, as it were, and rebuilds our society in a new form. We become creatures of money.

This form of rebasing is particularly intense, because money in turn becomes foundational to almost every other capacity that we have, but shallower forms of rebasing can be seen everywhere in our society. For example, in my piece Tech Doesn’t Make our Lives Easier. It Makes them Faster, I illustrated a related process with cars in Los Angeles. In the pre-car era, it would be unrealistic for a person to live 30km away from their place of work, so naturally they’d live closer. It was the car that made distant suburban living viable, and thereby catalyzed urban sprawl. Bear in mind that, once they reach a certain critical mass, capitalist systems begin to generate internal pressures to expand and accelerate, so when there’s a new chance for them to burst outwards - via cars, for example - they do. Urban sprawl is the result.

If you find yourself as a person growing up in that environment, your skills, options, expectations, sense of normality and needs are transformed by it. If you don’t have a car in a situation of urban sprawl, you’ll find yourself excluded from society, which means the ‘need’ for a car is catalysed by the car itself. Getting one doesn’t ‘increase your score’. It gets you to zero. The function of a car in LA is to enable you to not fall off the bottom of a society forged by cars.

Presentist delusions

A creature of money, like a creature of cigarettes or cars, fears the loss of the thing they’re dependent on, and imagines a growing ‘hunger’ if it were absent. This in turn generates the idea in their head that if this thing were to be removed there would be a problem. Rather than accepting that this problem only exists in their era, they project it back in time, inventing a historical story that casts their state of dependence as a ‘high score’, and one that some imagined past player must have strived to get to through acts of invention. ‘History’ becomes the act of justifying your current state, a phenomenon known as historical presentism.

A key presentist move is to project a half-formed version of your present-day world back in time in order to then fill in the missing pieces to recreate the full version. For example, the early inventors of cars never faced the problem of urban sprawl that a person who lives in a car-dominated world does, but that person might casually fantasize about those ‘terrible old days’ when people had to trundle 30km to work in an ox-cart, failing to notice that in a world of ox-carts people lived much closer to their means of subsistence.

Fantasies like these create teleological pressure: you feel a ‘problem’ in the past, a kind of vacuum, and the car steps in to fill it. The worst versions of teleological history are those that imagine that people in past had some intent to get to where we are today, but the general feature is that the past is seen as homing in on the present, rather than possessing a logic of its own (imagine people in the future thinking that things you’re doing right now are being aimed towards them, rather than being set in your own context as you look out into a vast unknown future).

The ‘inventors’ - accidental or otherwise - of money, did not stumble on a solution to some problem that already existed. No, as we glimpsed above, they had their own logic in their own time, but it’s true that money came to catalyze a situation of us becoming dependent on huge networks of strangers in vast-scale economies. If you find yourself born into that, having access to a monetary system is not some ‘positive score’ event. It’s a basic requirement to get to zero.

18th and 19th century economists like William Stanley Jevons, however, were creatures of money and wanted to cast this in ‘positive score’ terms, so fantasized a ‘history of money’ in which it was presented as an innovation that enabled people to escape the problem of barter (see How to Write a Flintstones History of Money). The ‘problem of barter’, however, like the ‘problem of trundling 30km to work in an ox-cart’ is a modern fantasy, not an ancient reality. Fine, there are historical examples of barter occurring, just like there are historical examples of people walking long distances, but the idea that it was the norm is absurd. The world of bumbling cavemen trying to exchange mammoth tusks for necklaces is a crude stone-age replica of a modern capitalist economy built in the mind of an economist. They simply take their their own situation - dependence on large-scale networks of people who trade specialized goods with strangers - and set it in world where it didn’t exist.

These presentist histories of money are also closely associated with functional descriptions of money. Functional descriptions are dodgy for a number of reasons (see How the 'Functions of Money' blind us to the Structure of Money), but one of those reasons is that they bolster the idea that money was created to solve some pre-existing problem. It treats money as if it were a tool we’ve ‘decided’ to use.

The classic ‘functions of money’ are - reputedly - medium of exchange, store of value, and unit of account. These are badly-worded descriptions that conceal more than than reveal, but, regardless of their accuracy, there’s just something icky about laying out a list of reasons for why we use money, because - let’s face it - nobody ‘chooses’ to use money. We use it out of an animal instinct, because everyone knows, and feels in their body, that if they don’t use it they’ll be totally and utterly fucked. Trying to describe this inescapable infrastructure with reference to rational choice is just weird. We are created by money. Of course we’re going to use it. It’s the catalyst for what we have become.

Reverse Rebasing

I smoked my final cigarette in 2019, outside Lima airport in Peru. I was in a state of terrible heartbreak, and decided to go cold turkey at the same time. I figured I might as well combine the two forms of pain into a singular mass to get it all over with at once. This certainly pushed me into the negative for a while. If an addict suddenly stops, they go through a few months of intense anguish, but slowly the body rebases and adapts to the new situation.

Coming out of addiction, I laughed at those ‘functional’ use cases for cigarettes that I used to find all around me. Some had tinges of reality: cigarettes do give a buzz (especially to the non-addicted body), and could be a great social lubricant, especially in places where you don’t speak the language. I was travelling a lot, so that function did contribute to my lock-in. Cigarettes could even be used for safety when lost in a dodgy part of a foreign city: lighting up makes it look like you have something to do, rather than standing around looking out of place.

I’m not sanctimonious about cigarettes, and don’t judge people who smoke, but I certainly recognise that all the ‘positive score’ functions are really justifications designed to invert the loss of internal agency - the hunger - that smoking brings. Once you apply this thinking to the realm of the money, you can see it everywhere. So much of our bragging about technological and economic progress is really just fear about losing stuff we’ve become dependent on, rendered as a list of justifications, functions and teleological histories.

But let’s get real. In some hypothetical scenario where cars were suddenly ripped away from society, people might experience a chaotic few months of long-distance trundling to get to work, but eventually Los Angeles would crack and fragment into hundreds of smaller villages. Similarly, if money suddenly ceased to exist, you would certainly experience a period of dislocation and chaos (and, as Ben Mahala points out in the comments, a large amount of death), and during that time you’d find random strangers trying to barter. What would eventually happen, however, is that the large-scale economy would fragment into thousands of smaller networks with closer social ties. All those alternative systems and non-monetary interactions that economic anthropologists have observed for a very long time would be recreated and foregrounded again, like diverse weeds waiting to resurge after a long period of suppression.

Of course, it’s hard to see how this scenario would come to be. While it’s possible to abruptly exit a smoking addiction, there’s no way to go ‘cold turkey’ on money, because we’re an interdependent species, and money underpins the entire system that every one of us relies upon for life-support. There are individual people - like the ‘moneyless man’ Mark Boyle - who find ways to withdraw from the social addiction, but some collective withdrawal seems highly unlikely.

I’m not a purist. I defend physical cash precisely because, in a state of addiction, we need a diverse range of suppliers of the thing we’re addicted to. The act of Uberising payments into digital oligopolies of banks and tech firms literally places control of our ultimate object of dependence - money - into a handful of corporations. That’s not progress. That’s enclosure.

I also don’t assume that a world without money is ‘better’ than one with it, but I’m not a solutionist who imagines that a world without it is ‘worse’. I think the solutionist mentality is not only deluded, but also deeply childish. When I turn up in tech, business and innovation scenes, I constantly hear versions of that mantra: We’ve escaped from our Level 1 world through our ingenuity, and now we’re on Level 7400 with a massive score and a huge inventory, and it’s only going to get bigger.

This giant inventory they imagine piled up is heavy. So heavy in fact that it sinks downwards and becomes the new ground floor of our existence. Here’s a provocation: technological and economic progress is all about us sinking deeper into a state of capture, having an ever bigger pile that all adds up to zero. The solutionist refusal to recognise that many of our gains are illusory, and that the drive towards high scores is - in the end - kinda pointless, is a refusal to recognise the contradictory, adaptable and morphing nature of reality.

Solutionism is also boring. Whenever I turn up at a fintech conference I’ll inevitably have to watch some tedious ‘history of money’ recited by a payments company exec. They’ll tell a half-assed teleological story that starts at barter and ends with Venmo, and they’ll cast this fake linear trajectory as a heroic tale of creativity, purpose, agency and problem-solving.

The actual creativity we should be striving for is to see around things, walk sideways, and hold contradiction. We should recognise the multiple levels of entrapment that we’re in, and accept that there’s no utopia waiting at the end of progress. There’s only Level 1, and in a world rife with inauthentic solutionism, simply acknowledging this is a revolutionary act.

I worked in a sugar factory in my youth and I remember the ten minute smoke breaks every two hours. The breaks made the mind-numbing work tolerable and then at the end of the week came the paycheck reward, which made the work week tolerable. It was all part of the system.

I researched tobacco once and discovered that the industrial process that made packs of cigarettes possible co-evolved with industrialism itself. In order to obtain the factory friendly texture, it was necessary to ‘toast’ the tobacco, which raised the nicotine level making cigarettes more addictive. The makers also adjusted the burn time of the cigarettes to align with the ten minutes of breaks.

I like the fact that this essay doesn’t have a solution. :)