A Lego Model of Capitalist Central Planning

If you think capitalism is about free markets, you're missing half the picture

This is part of my Lego Capitalism series, where I create simplified models to help you visually navigate the complex webs of global finance. Audio version coming soon

We associate central planning with old command-and-control Communist economies, where bureaucrats would sit in a central agency and try to monitor and control what production was happening where: We need 5,000 harvesters to reap the wheat, but the vehicle plants are short on steel, so mobilise the iron ore mines.

Centralized coordination like this is difficult, because supply chains often double-back on each other, with a shortage in one affecting all the others. The attempt to make central planning more nimble even inspired cyberneticists like Stafford Beer, who worked on the fabled Project Cybersyn in Chile in 1971.

Project Cybersyn was an experiment in ‘cybernetic socialism’, but was disbanded in 1973 after a US-backed coup brought a neoliberal warlord called Augusto Pinochet to power. Pinochet immediately set about murdering and imprisoning opponents in order to bring free markets to Chile, a process that would involve letting mega US corporations sidle into the country.

When you really think about it, the idea that corporations represent free markets is kinda ridiculous. Take a company like Walmart, for example. It consists of 2.1 million people, which is similar to the size of the entire population of England in the early 1500s when capitalism was kicking off. Unlike 16th century artisans and merchants, however, the employees of Walmart are almost entirely directed from above through Walmart’s vast internal central planning systems, implemented through hierarchal departments with quotas and performance targets that would make anyone who designs a Soviet Five-Year Plan proud. In fact, this was the topic of the 2019 book The People’s Republic of Walmart.

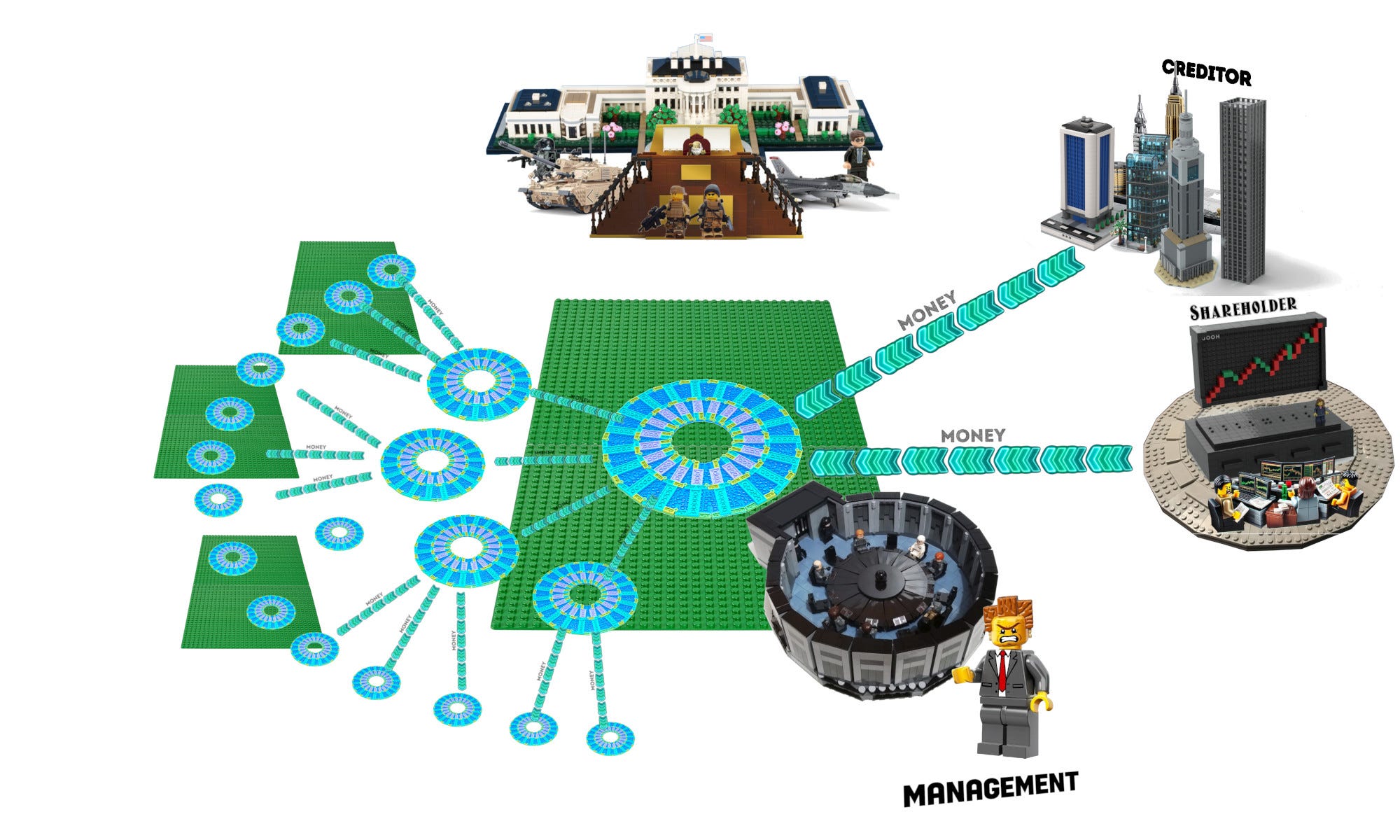

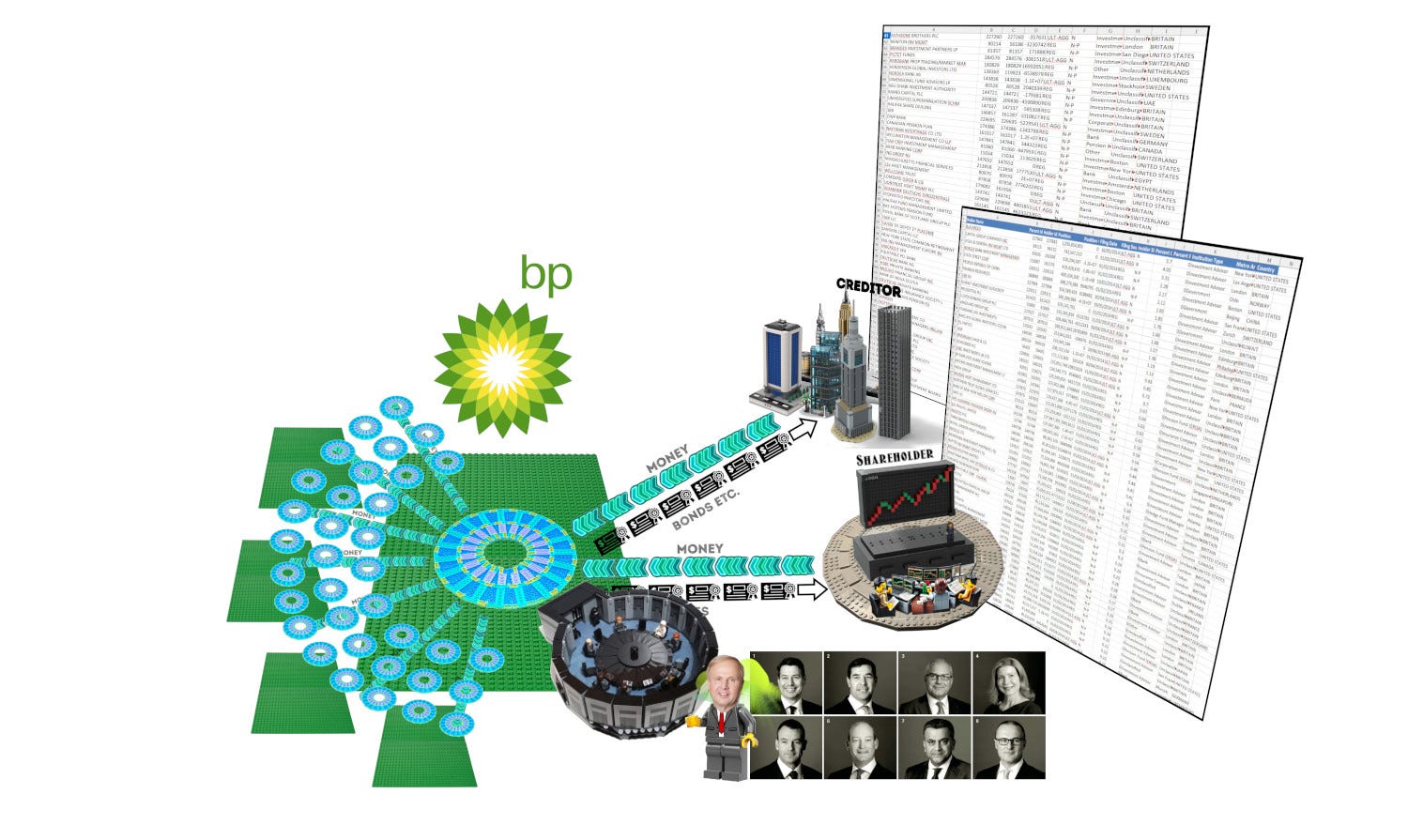

My Lego Capitalism series has been showing that a corporation is not a single ‘thing’, but rather a system, in which a federation of interlocking groups organise around a legal focal point. In the centre is a legal entity written into existence through law. It gets capitalized by the financial sector and is subsequently controlled by managers that direct its money to mobilize workers and suppliers to run assets that will output goods to customers that will send money back out the circuit to the financiers.

The image above has been useful, but it has one major weakness. It makes it look like there’s a single legal entity that everyone revolves around, when in reality a transnational corporation is an elaborate network of legal entities, called subsidiaries, spread across the world in different jurisdictions, and it’s these subsidiaries that actually hold most of the assets or hire most of the workers or do deals with suppliers. To begin to glimpse this, we must picture the main corporate entity branching out and capitalizing a whole range of sub-entities…

Corporate subsidiary structures can vary in complexity. For example, the British media giant WPP has over 2100 subsidiaries, while Big Pharma giant Glaxosmithkline has a simpler setup, with a moderate 280. In 2014, though, I got a rare opportunity to do a deep dive into the corporate structure of the oil company BP, which at that time had 1180 subsidiaries. I worked with a group called OpenOil to trace how these sub-companies interlocked. The chain started with the mothership company - BP PLC - in London, which then branched out across the world via subsidiary chains that went 12 layers deep. I spent days manually stitching together the connections to come up with this picture…

Doing this gave me a visceral sense of how corporations are feats of legal engineering, elaborate meshes of entities written into existence by lawyers across jurisdictions and bound together via contracts. It impressed upon me just how hard it is for nation states to have any control over these extra-national clusters. It also gave me a glimpse into how these clusters are controlled via central planning systems.

From the London headquarters, BP’s corporate bosses can monitor and control the production of these subsidiaries, and direct them to ‘sell’ the outputs to each other. This is called ‘intra-firm trade’, and it accounts for 30% of world trade. I shit you not - a third of world trade happens inside companies, totally insulated from open markets.

In 2014, BP had around 85,000 employees across 1180 companies. If you showed a person in 16th century England those numbers, they’d think you were referring to an entire economy. Well, it is an entire economy, but it’s entirely subsumed under a single brand name. Let’s take a brief tour through this ‘economy’ of BP in 2014.

The BP Economy in 2014

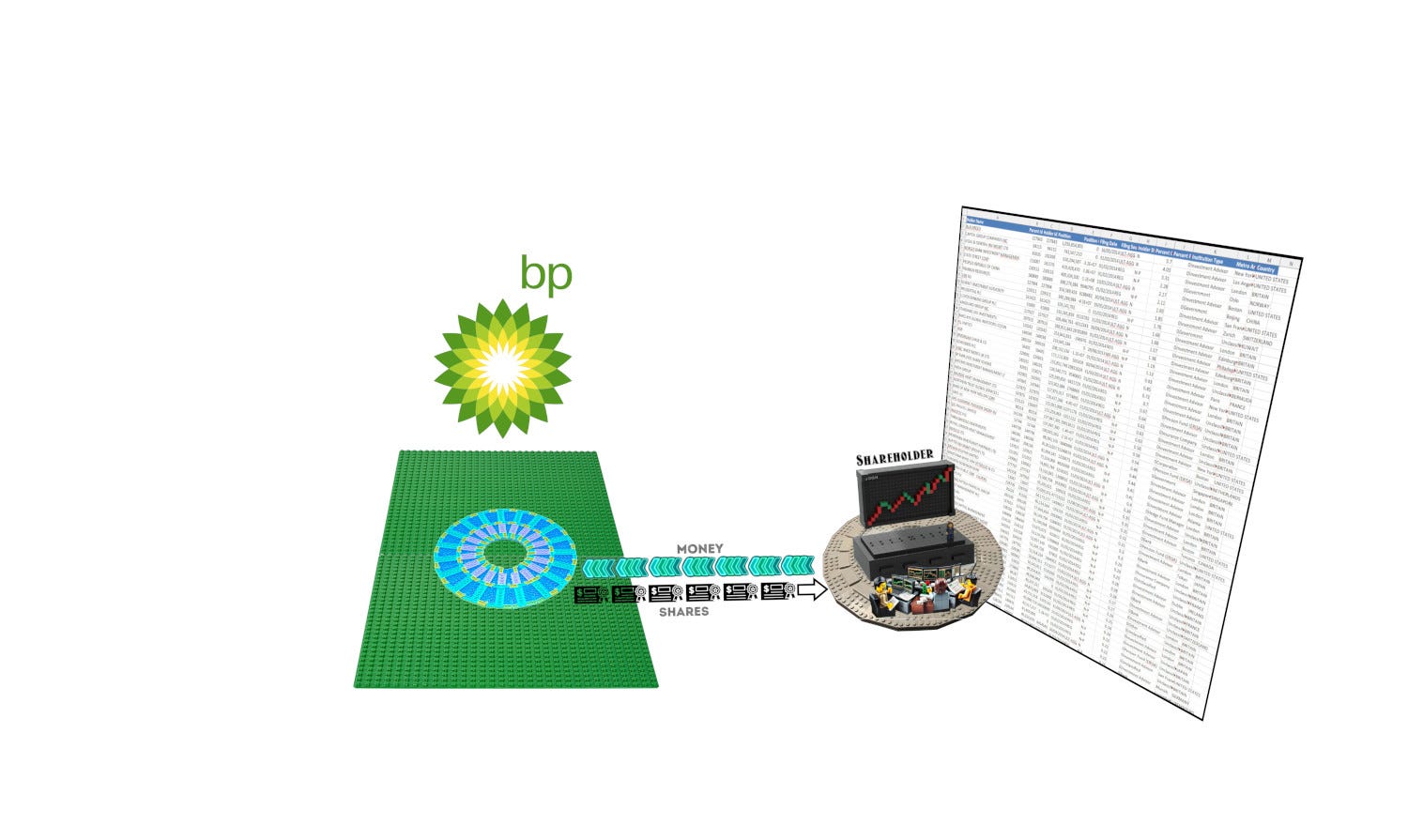

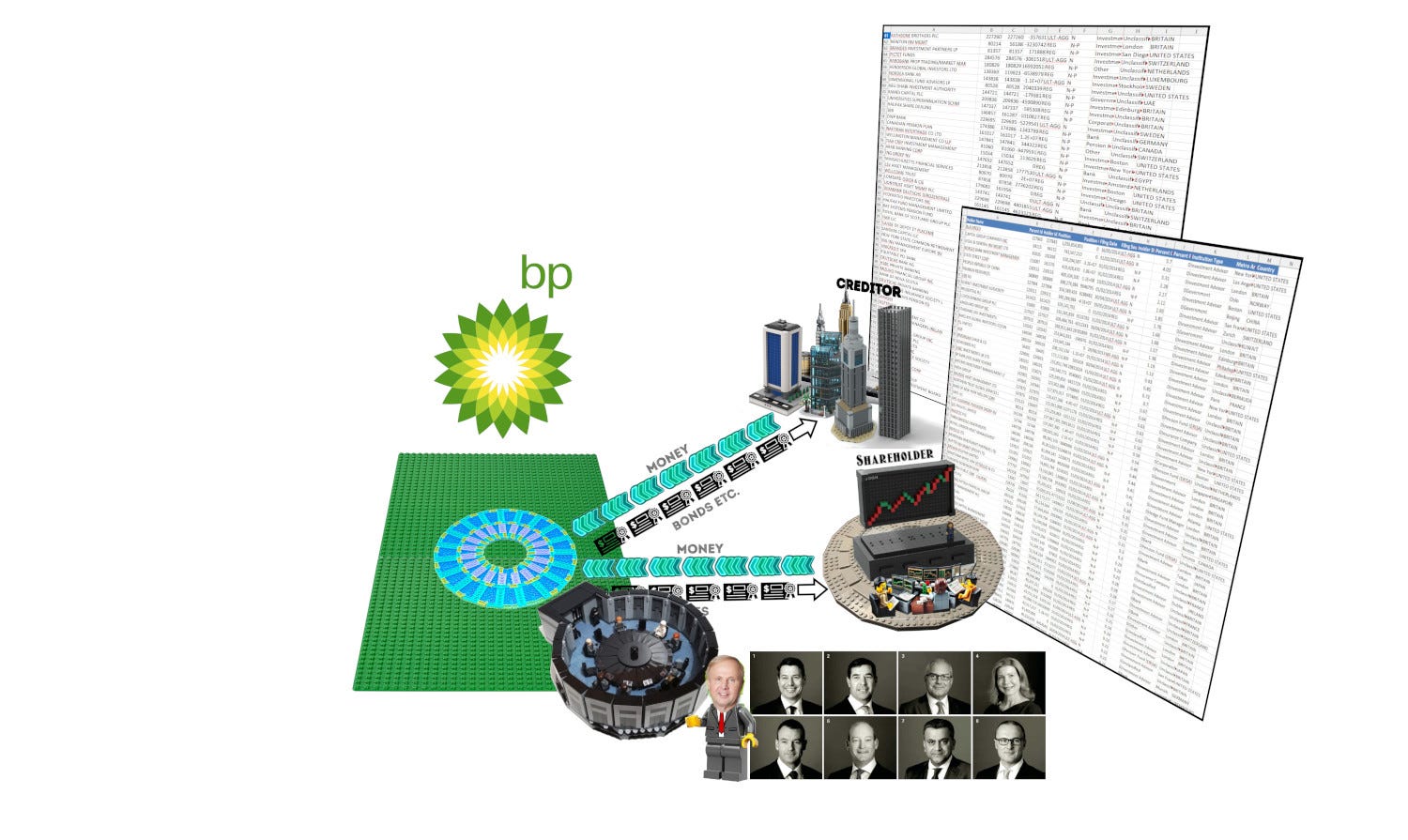

The first thing to say about the internal economy of a corporation is that it’s privately owned. I’m sure many of you have been served adverts by stock-trading companies that encourage you to open accounts and buy shares of ownership in corporations, but retail shareholders like us only hold tiny crumbs of this ownership. The biggest chunks of corporate shares are held by institutional shareholders, which includes mega funds and even governments. Here’s a sheet of BP’s biggest institutional shareholders in 2014.

The world’s most powerful fund manager - Blackrock - was BP’s biggest shareholder in 2014, holding 5.7% of the company’s shares, a stake valued at around £5.3 billion at that time. The big insurance fund manager Legal and General was holding 3.31%, while US pension fund CALPERs held 0.33%. Also notable are the sovereign wealth funds like Norway’s oil money manager Norges (2.28%), the Kuwait Investment Authority (1.78%) and the People’s Republic of China (2.11%). There were also a bunch of hedge funds, like David Einhorn’s Greenlight Capital (0.09%), and foundations like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (which eventually divested in 2016).

The spreadsheet above only shows the first 57 of 812 institutional investors, and the exact composition would have changed by now, because big investors are always moving in and out of different corporate entities. In a sense, these investors get to dock into, and back out of, different centrally planned economies, picking and choosing them as the rise and fall. So, let’s imagine this list of shareholders docking into the BP internal economy, handing over money for shares.

BP’s Central Planners

These different shareholders who capitalize the company don’t operate the company. Rather, that’s delegated to a team of central planners we call management, who technically work for shareholders (albeit, in reality it’s only very large institutional shareholders, such as Blackrock, that have a direct line to them). Formally, though, all shareholders are supposed to be represented by the board, a hybrid body that has various external executives who’re supposed to keep an eye on managers and make sure they’re doing their job properly.

The chief central planner is called the Chief Executive Officer. The CEO is supposed to be the one with the most accountability, and is also the one to get axed when things go badly wrong in the centrally-planned operations. This is what happened to BP’s Tony Hayward, who was forced to step down after the Deepwater Horizon disaster in 2010. His apologies for this massive oil spill were immortalized in South Park…

Tony was replaced by Bob Dudley, and in 2014 Bob was presiding over a team of senior execs in control of different central planning command posts, such as securing financing, dealing with supply chains, buying up assets, making strategic decisions and breaking into new markets.

The natural habitat for corporate central planners like these is the boardroom table, where they meet to make decisions that have ramifications across the globe.

Just like officials in Communist regimes, who have to hit various targets, corporate central planners must try to please their bosses - shareholders - while trying to maneuver the unwieldy moving parts of the corporation amidst the unpredictable chaos of the world. One of the primary goals of central planning is to get rid of such chaos. The execs must secure the corporation in the world, minimizing risk while maximizing shareholder returns.

But, while old Soviet bosses measured success across reasonably long time horizons like five years, corporate central planners are under constant pressure to show results. This is because shareholders, who previously docked into the BP ecosystem, can detach at any point and join a different centrally planned corporate economy. This competition between centrally-planned systems for financing can lead corporate managers towards short-termism, where they try to boost profits by cutting corners, ignoring environmental damages, or resorting to accounting fraud. One classic way to boost shareholder profits, though, is to use leverage, and that involves getting creditors involved.

Bring in the debt investors

In my Lego Model of Financial Capitalism I showed how a small real estate company might finance a building in chunks with a combination of equity - shares - and debt in the form of loans and bonds…

The example above concerns a mere $100 million, but mega corporations operate at vastly bigger scales. In 2014, for example, BP was raising about $8-15 billion from bond investors each year, relying on investment banks to arrange these deals. Here are some of those deals from that time:

In Oct 2013 they raised 1.2 billion Renminbi, arranged by Bank of China, HSBC, ICBC International and Standard Chartered Bank

In Nov 2013 they issued a CA$450 million bond, arranged by Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, and Toronto-Dominion Bank

In February 2014 they issued a $2.5 billion bond arranged by Barclays, BNP PARIBAS, Credit Suisse, Mitsubishi UFJ Securities, Morgan Stanley and RBS

In February 2014 they issued a €2 billion bond, arranged by Credit Agricole CIB, Goldman Sachs, HSBC, Lloyds, Mitsubishi & Santander GBM

Much like you might try to build a credit rating for yourself through strategic borrowing, they deliberately borrow from different debt investors in different regions to keep those investors sweet. Nevertheless, while we can trace who the major shareholders are in BP through regulatory filings, finding out who these lenders and bondholders are is a lot more difficult. What we do know, however, is that they will include many of the same big institutional investors that invest in shares.

For example, the Teesside pension fund is a shareholder in BP, but upon browsing its annual report I found that it had also lent money to BP via bonds issued in Chinese Yuan and Swiss Francs. This means it’s sending money to BP in different forms - sometimes as a shareholder and other times as a bondholder. In any case, it’s useful to view shareholders and creditors as forming a common financing front, collectively financing the corporation side by side.

Financial Central Planners: The Corporate Treasury

All that bondholder and shareholder money that enters BP PLC ends up in bank accounts controlled by the corporate entity. For an external investor, this money seems to enter a black box and disappear, re-emerging at a later date in the form of interest paid out to bondholders and dividends paid out to shareholders.

But what actually happens inside the black box? Well, the money that enters ends up under the command of the Chief Financial Officer, which in 2014 was Brian Gilvary, the central planner in charge of the BP Treasury, a department which, in BP’s own words, acts as “BP’s in-house global bank, ensuring it has the right funding, liquidity and currency in the right amount on the right day, and in the right place."

The Treasury is the interface between the external world economy, and the internal BP economy, in charge of raising money from external investors and then pushing it around the internal BP ecosystem. In fact, the BP Treasury ends up acting as a financier, capitalizing 35 subsidiaries…

These 35 sub-companies then capitalise 152 sub-sub-companies, which capitalise 284 sub-sub-sub companies, which capitalise 223 sub-sub-sub-sub companies. This goes on until we get twelve layers deep. That’s how we get 1180 companies over 84 national jurisdictions. Let’s follow one of these chains across the world.

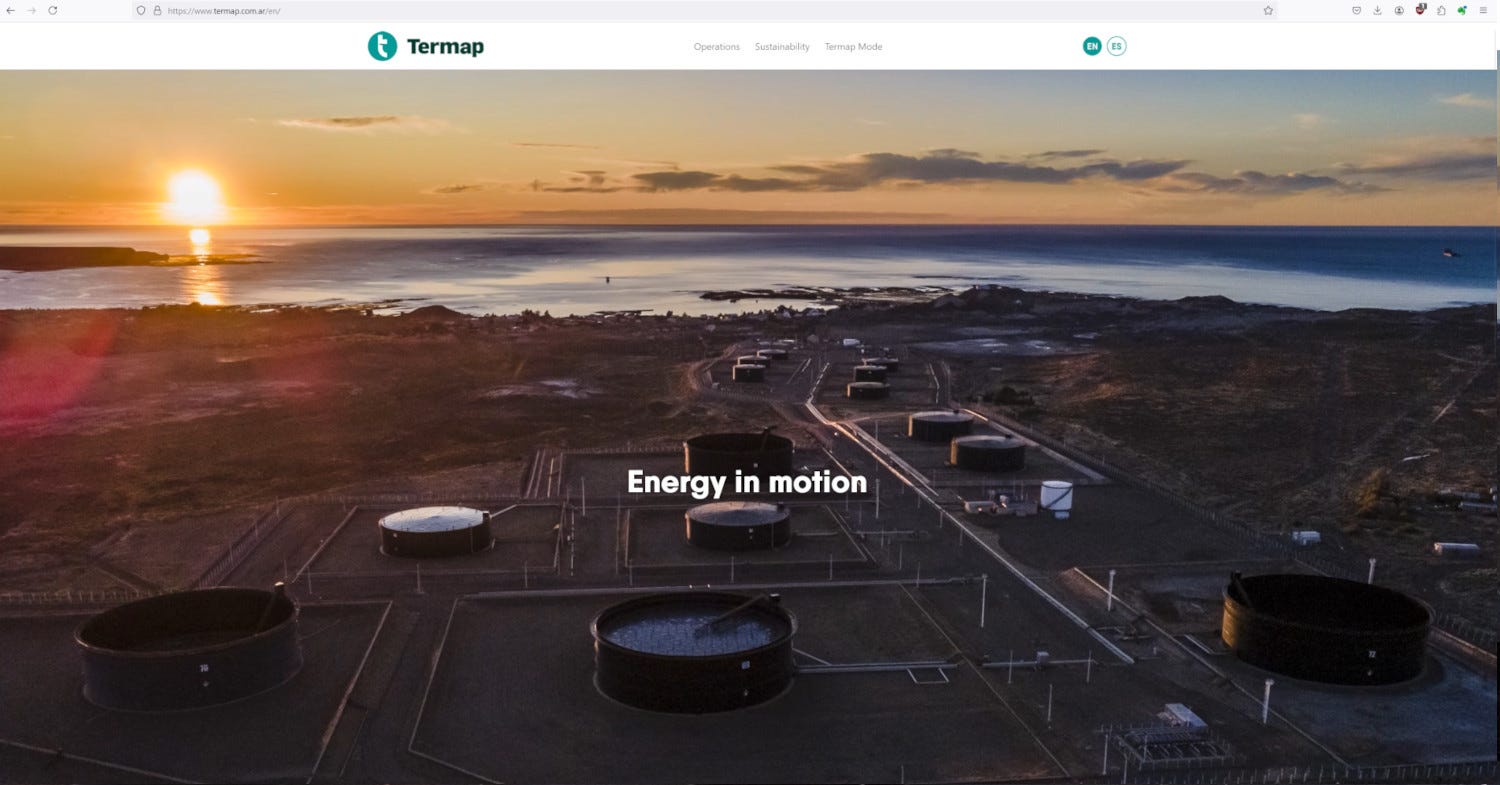

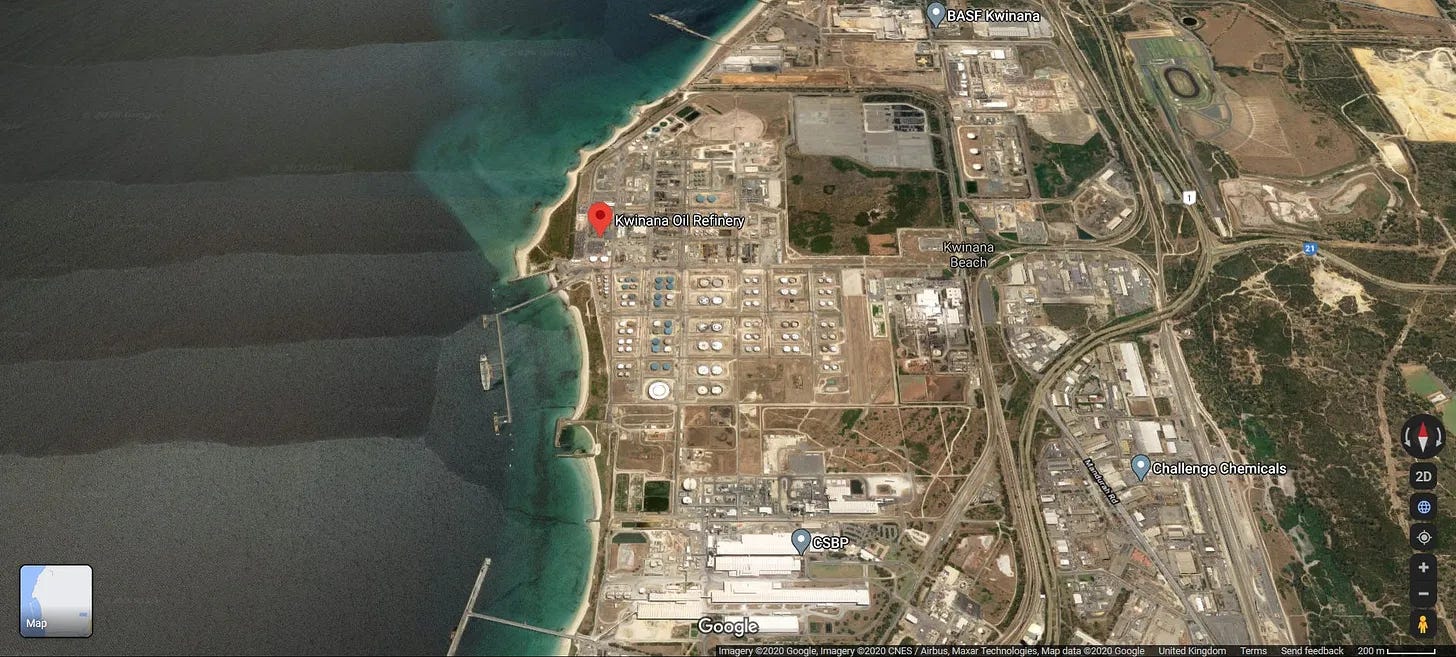

What’s going on here? Well, BP PLC owns BP Holdings North America Limited (UK), which owns BP America Inc (USA), which ripples ownership through another six US subsidiaries, the last of which owns Pan American Energy Holdings Ltd (British Virgin Islands), which owns Pan American Energy (Uruguay), which owns Pan American Energy Ibenca (Spain), which owns Terminales Mantimas Patagonicas SA (Argentina), which is this…

In the example above, each company in the chain takes the position of an equity investor - it owns the shares of the next company - but they can also start lending to each other. Try follow this convoluted financial circuitry from BP’s Baku Tbilisi Ceyhan pipeline.

BP Pipelines Ltd is owned by BTC Pipeline Holding Co (UK) which is owned by BP Global Investments (UK) which is owned by BP PLC

BP Pipelines Ltd, though, is also receiving a loan from BTC Finance BV (Netherlands), which is receiving a loan from BP International (UK)

BP Pipelines Ltd, though, owns BTC Pipeline Holding BV (Netherlands), which owns BTC Finance BV, which is the one that’s lending to BP Pipelines Ltd

So, we have a subsidiary that indirectly owns the very same subsidiary that’s lending to it, like a parent giving pocket money to their child and then borrowing it back. Who knows why BP’s legal engineers decided to create this particular structure, but - in general - these weird chains of subsidiaries are designed to get around various national laws, and - especially - to avoid tax.

To understand this, we need to realise that these company chains act as conduits for the BP entity to snake out across the world. The central planners take that money that originally entered via players like Blackrock, and they cascade it through the subsidiaries in the form of equity or debt, which will end up being used to buy up assets and mobilize workers to make stuff, which will be sold for money that will be drawn back up the elaborate company chains via dividend and interest payments, to eventually exit out the mothership in London, and to Blackrock (and maybe to you).

At a generic level, what’s happening here is money going out, and then being sucked back, but it makes a difference as to what legal classification the money has. For example, if BP wants to push money to a subsidiary that does operations in a distant high-tax jurisdiction, it might make sense to channel it as a ‘loan’ (via another subsidiary in the Cayman Islands, for example), because this will allow the central planners to suck the money back out in the form of pre-tax interest, which has different tax treatment to dividends. This practice is sometimes called BEPS - base erosion and profit shifting. Essentially, the central planners take a profitable subsidiary and ‘erode’ its profits by pulling the money out in disguised forms, such as consulting, licencing or management fees paid to another subsidiary. This is a core pillar of transnational corporate tax avoidance.

When looking at these strings of subsidiaries, you need to see them as a fossil record of attempts to optimise profits across the world, each chain being but one circuit within a meta-circuit. In fact, if we trace all the subsidiary connections that emmanate out of the aforementioned BP Global Investments, we get this…

The politics of captive capitalism

Not only does BP have a centrally-planned ‘captive’ financial system within itself, but it has an entire captive economy. If companies have corporate personhood, then subsidiaries are like corporate sub-persons, dominated by the main company which can make them do deals with each other, lend to each other, or charge each other too much to erode revenue in one country and make it appear somewhere else.

In the end, though, these complex chains of subsidiaries are but hollow legal entities that need actual people to do the work. BP’s senior managers might be in London, and might be accountable to players like Blackrock, but they need workers across the globe to turn up in distant operations in Nigeria or Australia, or at Termap in Argentina. Each country they operate in might have separate union laws, environmental regulations (or lack thereof) and labour conditions. Each country also has its own political elites that want placating. So, being a senior manager in a transnational corporation is inherently geopolitical, especially in the case of companies like BP, which control access to strategic energy sources.

In the capitalist system, profit emerges if input costs are lower than output revenues, so to reduce the former managers might seek to drive down wages of workers, and dominate over suppliers, each of which carries its own geopolitical risks.

More generally, managers might seek to play parties like that off against each other by replacing (or threatening to replace) workers from one country with machines that they buy from suppliers in another. At the same time, they might face pressures to keep stability, and that may involve trying to reward loyal workers, buy off local politicians, or to grant suppliers long-term contracts to keep them aligned. The day-to-day life of a BP manager, then, involves balancing off a range of parties, cutting tax deals with different governments, or lobbying against new policies that may affect them, all while trying to suppress worker unions.

Above all, though, our central planners will be paranoid about fending off other central planners who coordinate other companies. After all, they face humiliation if they lose market share, and may even face getting fired by the board for failing at their task. One of their worst fears is being targeted by a powerful activist shareholder who will buy up shares in order to get a board seat, from where they can harangue the CEO. For example, Disney’s senior managers recently defeated the activist investor Nelson Peltz…

We seldom feel sorry for these senior managers, especially because they get paid millions, but they often project their own stress downwards to more subordinate middle-managers. To this day, one of the most entertaining series that covers middle-management life is The Office (US), which follows Michael Scott, the hapless branch manager of a regional paper corporation, as he tries to be a nice guy that keeps his workers happy while he faces top-down pressure from ‘corporate’ (the name he gives to the distant senior management). Even within his branch he finds himself having to navigate between the demands of the white-collar workers upstairs and the blue-collar workers in the warehouse below.

This series perfectly captures the ‘sandwiched’ experience of a middle-manager, caught between different levels of the corporate structure. In many ways the job of Michael Scott is not dissimilar to the job of a local party functionary in a municipality in North Korea. He’s supposed to take charge of a small fiefdom, and must fall if he doesn’t. We’re trained to see Capitalism and Communism as diametrically opposed entities, but in reality, human society is not dualistic like this. Every capitalist system has many centrally-planned elements, just like every communist system has many market elements. Much of it comes down to what you want to see.

For a long time I’ve tried to propose the idea that free markets don’t actually drive innovation, rather in the global capital world it starves it.

The consolidation that is hidden from the average persons is predominately giving many “markets” an incremental approach. This has to play into aspects such as medicine and other important markets. Markets where incrementalism is criminal and obscene.

Having these private companies whom the well being of the populations of the world’s health operate like Apple is a travesty. If I may harken back to my point, along side this I’ve often paralleled these actions as inverted, get ready…

Communism! The means of production so monitored globally has taken control and created a framework by which these artificial markets are the board member’s dream! Almost completely predictable! Of course I’m leaving out many factors, and actors but the aforementioned dots laid out by you Wes are more than apparent.

Yes. Chile under Pinochet wasn't doing "free markets it was doing cartelization and private sector central planning. In Chile under Pinochet the government was not too infrequently literally mandating production for a lot of SMEs, mandating their sales destinations., other things Central planning.

And the crowd of people in the USA who backed him eventually were able to the scheme over here in the 1970s and then really ramp it up in the 1980s under the Reagan admin. Take the airline industry as an eample, I mentioned to Mike in another post in this reply space, they airline industry. An element within the Reagan admin seems to have been set up, that took formal actions, that in conjunction with private industry (and I suspect Big Finance), took actions in at at least one huge aspect of the airline industry and behaved in a way that was like halfway towards being a Soviet industry control committee when through a variety of actions (some of which could be argued to be in essence illegal as they required twisted interpretations of the Airline Dereg Act) contrived the Airports hub-and-spoke system that we have today. And the airline industry is actually on teh smaller end of what they did in these regards, its simpler to talk about because it was more direct.

There's a good book, its an imperfect and also old so it doesn't capture big recent stuff like post 2008 stuff of things that had formed/further developed in the 90s/2000s, but it a pretty good book if your interested in the subject matter, its by John Munkirs and its titled 'The Transformation of American Capitalism: From Competitive Market Structures to Centralized Private Sector Planning'