The Emptiness Machine

How generative AI is trying to rip the screaming soul out of the Enlightenment

Want to listen to this article? Paying subscribers can find the audio edition here

As an economic anthropologist, I don’t get romantic about the so-called Age of Enlightenment. The Age, which starts from the 17th century onwards, is given star treatment in many conventional accounts of Western civilization. We associate it with the ascendency of reason, science, mathematical breakthroughs and theoretical advancements that produce wondrous new gadgets. No doubt it was a heady time for certain narrow classes of people, but anthropologists know its shadow. The pretence of bringing reason to a dark world often rode alongside violent expropriations and colonialism, which were further justified through wack dualisms like Man vs. Nature and Mind vs. Body. If I was to rewrite the Wikipedia summary of the Enlightenment, my cynical side might just edit it to: An Age in which European men developed a high opinion of themselves as transcendent rational beings steering the chaos of irrational nature, women and the body.

René Descartes (1596-1650) is often attributed as the one who blessed us with the dubious vision of mind-body dualism, but he was just playing into an emergent spirit of the times that was beginning to view rational thought as the true essence of humanity. For a long time before him, people believed in another floaty entity that surged around in the vessel of our bodies - the soul. Sometimes that was imagined as a warm vapour or fiery tempest hanging out around in the chest area, but Descartes felt the soul was rational, and was residing in the head, and was pretty much the same as the Mind.

This attempt to push the soul into the head doesn’t go unchallenged. While the Enlightenment gets called the Age of Reason, we also associate it with Expression: great artists, composers and writers harnessing the new technologies to give colour to the reason. The artistic movement called Romanticism is often described as a reaction to the Enlightenment, but it’s kinda like its angsty, more soulful twin that grows up alongside it. Listen to Beethoven summon emotions in the great concert halls amidst the industrial revolution. Look at Turner channelling the turbulence of colonialism with his moody pictures of slave ships on rolling oceans.

‘Soulful’, in this context, denotes a return to the heart area, a pulling away from rationality, the overlooked twin reasserting itself. This desire to give the mechanical march of the scientific-industrial juggernaut a heart and soul is a trope that has remained popular into the modern era. It was picked up in The Wizard of Oz (1900), with the Tin Man who wanted a heart. It’s also a central theme of the groundbreaking Metropolis (1927). The film begins with Cartesian Mind-Body Dualism, with a capitalist elite represented as The Mind, controlling a body of workers, represented as The Hands, in a soulless, mechanical world of industrial grind. The resolution is the Heart, which joins Head and Hands together.

One of my favourite board games is 7 Wonders Duel, a civilizational game that you can win through three primary methods:

Military victory, where you crush your opponent

Scientific supremacy, where you out-invent them

Civilian victory, where you shame them through your balanced accumulation of science, military defence capacities, commerce and great works of culture and art

Duel’s civilian victory path seeks to balance violent militarism and analytical rationalism with a touch of the beautiful and artistic, and this need to fill in the emptiness of domination with soul permeates modern capitalism. For example, when I worked in high finance, the senior bankers felt it very important to be able to discuss the latest science, tech and business trends with clients, but equally important to display their knowledge of fine art, music, and philosophy.

It’s common for financiers to collect art as a form of conspicuous consumption, but hanging those pieces on the wall of their penthouse suites also represents a desire to balance out the ruthless job of extracting profit. The fear of being a mere capitalist or mere dominator is common in elite circles, which is partly why they crowd the operas and get weepy about the great paintings, but we find versions of this throughout society more broadly. The cool urban middle classes love to be at the forefront of new tech, but also want to be seen at the art gallery.

In modern pop psychology terms we might view this through a ‘left brain vs. right brain’ framing. Regardless of how accurate the neuroscience of that is, we understand what the distinction is trying to get at. The ‘left brain’ is that more heady, tightly-wound, trebly buzz some people get from technical or analytical problem-solving. The ‘right-brain’ is that more chesty, holistic, looser, bass-heavy frequency of creative expression.

Solving problems can certainly be creative, but it often involves a form of domination. You fix a problem, destroying some chaos to set something in place, to create completion and stable order. Other forms of creativity are more open-ended, less about fixing-in-place and more about releasing, destabilizing and freeing up. These twin poles of creativity do segue into each other, and can even co-exist in single acts of creation, but have a tense relationship. The Enlightenment is often imagined a time that freed people from religion, and yet - when push comes to shove - it has a distinct fixing vibe, a desire to use rational thought to impose order, to steer Creation and make us masters of our destiny. So, when Enlightenment thinkers referred to multi-gendered humans as Man, they were not talking about actual humans, but rather about their one-sided ideal of a rational problem-fixer. It is Man at the helm of the juggernaut of industrial progress, with its militaristic states and megacorporations.

It’s probably no coincidence then that we talk about The Man to refer to capitalist elites and authorities. In a sense, The Man is Man viewed through the eyes of the tormented twin. As (The) Man tries to control destiny, the twin tries to loosen it up, two intertwined spirits fighting to exorcize each other. Each era brings its own unique combinations of this. Look at 60s rock using electricity-powered tech to amplify the spirit of romanticism and the sexual revolution, before that innocence is shredded in the hard-edged 70s, and then gutted by record companies in the 80s with kitsch glam metal, which collapses under its hairspray as underground rap bubbles up through the streets. Watch Nirvana emerge from the wreckage in the 90s with their fuzz pedals, screaming fuck you to The Man. Watch The Man screaming fuck you back at them via derivative jock-rock and commercial rap by the 2000s. Capitalism is constantly trying to appropriate and eat the very angst it generates.

Man, and His Creativity Machines

Last year was a big moment for Man, because a new subset of automation that could deal a blow to His romantic twin was popularized. Generative AI is a scientific-industrial tool built for the automation of creativity, the automation of moody landscapes, the automation of angsty rebellion, the automation of pretty much any creative expression we’ve previously expressed. It can even automate critique of automation, and then automate that again. It might even use this article to do that.

In mythic terms, generative AI is The Mind creating a mechanical replica of Heart and Soul to give to the Tin Man. I’m sure the people at ChatGPT, Stable Diffusion, and all the other generative AI companies are very talented and well-meaning, but they are very much on the tool-building, problem-solving, rational transcendence side of the Enlightenment. They’re not artists, and they mostly work for capitalists, or venture capitalists, who pay them to lose themselves in the stimulating task of building wondrous machines. They seldom think about how their machines will be weaponized, and disassociate themselves from responsibility.

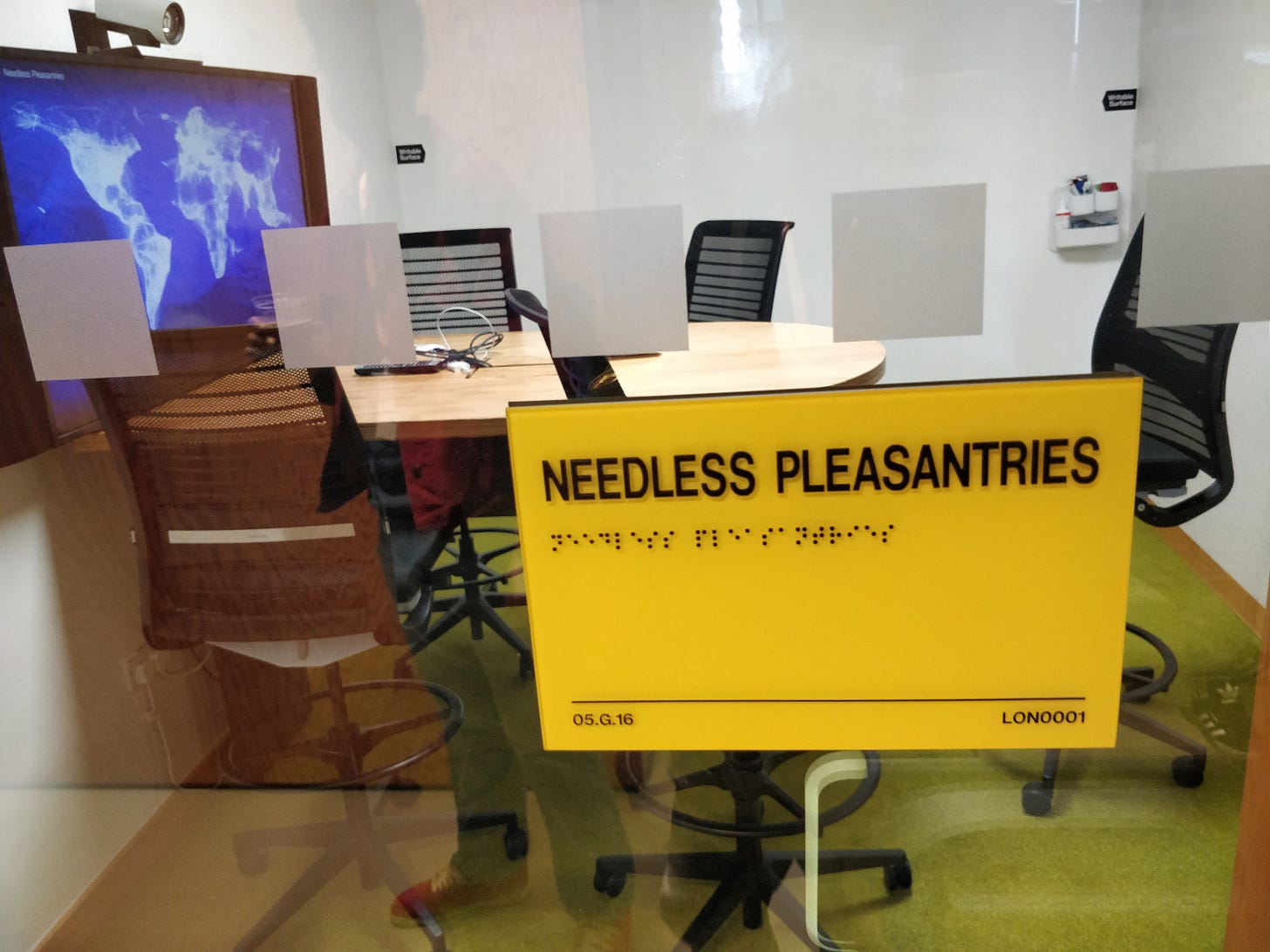

I remember visiting Facebook’s London offices. It was one giant model of faux playfulness, with foosball tables set on AstroTurf, life-sized Ninja Turtles, meditation chambers, and meeting rooms with names like ‘Excessively Loud Tutting’ and ‘Needless Pleasantries’.

The offices were explicitly designed to be a play-pen for geeky adults, but this is the company whose various products lie behind vast political disorientation, teenage cyber-bullying, body-shaming, and far-right radicalization with real-world violent effects for actual communities. I found myself weirdly longing for the steel-and-glass skyscrapers of high finance. At least the finance sector doesn’t pretend to be saving the world, and doesn’t cloak itself in a childish image of wacky creativity. Financiers have a certain grim authenticity about their narrow interests.

When pursuing those narrow interests, financiers do put money into those funds run by the venture capitalists, and those are used to mobilize the tool-building-problem-solving impulse of the tech class, but that narrow form of creativity is narrowed even further through the evolutionary processes of this financing. Financiers will avoid, and thereby screen out, any firm that actually proposes anything authentically radical, so the startups only get to express creativity insofar as it aligns with the conservative requirements of corporate profit-seeking. That’s because, in the final analysis, the corporates are the apex power-players in the ecosystem of corporate capitalism.

When we zoom out, mega-corporations are like undead programmes that default towards optimizing profit. They’re drawn towards other profit-optimizing machines, which is why they default towards seeking out automation, and why the venture capital class defaults to funding new forms of automation. So, how does generative AI fit into this schema?

Well, the productive foundations of capitalism lie very much on the side of quasi-militaristic industrial science, but to sell the results, firms also need to mobilize that romantic part of ourselves. They have to make you feel things, and traditionally they would have enlisted musicians, artists and writers for these public-facing heart offensives. This is also a historic source of inner conflict for those artists, who fret over whether they really should be selling out to The Man. Here, for example, is Justin Hawkins of The Darkness discussing his music being used in awful commercials.

Often these artists channel a form of creativity that comes from the body. Musicians feel the music they play, and artists feel the act of creation, much like a child feels the joy of pushing a crayon over paper. The actual end product is only one part of the process, but it’s imbued with feeling and makes us feel. This creation takes energy and time, though, and hiring people like Justin Hawkins to go through that process is far more expensive than simply generating an automated replica of the results.

So, venture capitalists fund the geeky tool-builder class to build creativity machines that can be used to cut costs. Generative AI is the spirit of industrialism attacking the spirit of romanticism, a machine to mimic the creativity of the twin, but stripped of the cultural substance. 2023 was the year it hit the big time, and along with it came all the media hype that presented it as One Giant Leap for Man. Deep down, though, we all know it’s one giant leap for The Man.

The scream

Much has been made of Marc Andreesen’s Techno-Optimist Manifesto, in which the venture capitalist rails against ‘pessimists’ who doubt the Enlightenment dream. But why did he decide to rehash this old ‘technology and markets will lead us to utopia’ line in 2023?

Here’s why. The 20th century version of the Enlightenment story told us that automation would release us from toil - destroy all the chaos of nature, blah blah - and leave us to relax doing poetry, music and philosophy. 2023 was the year capitalism called that off, saying actually our engineers have poetry, music and philosophy covered too. They even went back on the story of our Mind being ever-so valuable. Rather than thinking, we’re now we’re told to learn prompt-engineering, and to be a grateful consumer of the result. 2023 was the year when the emptiness of the automation vision started to creep into our souls. We feel an inner scream somewhere, coming from that romantic part of our being.

Marc’s VC industry heavily pushed the automation vision, but is now threatened by public and regulatory blowback, so he wants to pre-emptively shame anyone who starts to have doubts about his progress narrative. That’s why he published his manifesto. That’s why he, and others, will spin that story of automation technology as representing epic creativity, and of creative young people embracing AI.

Of course we still have a creative spirit, and of course we all still live in a vast interdependent market economy which requires us to constantly compete, which means all of us get pulled into using the same machines out of fear of being ‘left behind’. So yes, he is right that there will be a generation of young people trying to ‘move with the times’ by using AI for new things, but make no mistake: the generative AI moment is the first time we have seen such a full-frontal assault on the romantic twin of the Enlightenment. It’s a definitive statement that scientific tool-builders are on top and creatives below, mechanical form over emotional substance. The crayon in a child’s hand is now Craiyon, generating simulations of Turner’s turbulent feelings.

Marc doesn’t want us to have doubts about the Enlightenment story, but anyone who doesn’t have doubts isn’t paying attention. Simulacra machines are spreading everywhere, while ChatGPT founder Sam Altman now feeds you half-arsed stories about his Worldcoin programme that’s supposed to solve technological unemployment through crypto UBI, provided you submit yourself to eyeball scanning. Worldcoin is backed by Andreessen’s venture capital fund, and now they’re running guerilla marketing campaigns on the streets of Berlin, where I live. I’m forced to walk over their simulations of urban creativity stencilled on the pavement, and when I look at their slogan - you must be human - I can feel the heart of emptiness beating in the VC-funded soul of techno-capitalism.

Perhaps it may lead to a blossoming of local talent. People learning, and playing and making and doing together... just for that sake of the experience - as people once got together to sing around the piano for no other reason than to sing. Not to make money or to show off their talent for an audience... just to sing, and to dance and to play charades and tell stories to each other. In the end, what's the point of consuming another AI generated image or video or song or article? If it helps to teach you something, well and good. But then what is the purpose of learning? If it is for the sake of mastery itself, and for the enjoyment of company... that seems to me to be a worthwhile exchange :)

Fantastic piece Brett, and I think complemented rather well by this from Bertus Meijer:

https://bertus.substack.com/p/image-generation-beyond-better-and

As you imply, it's not the product that matters, it's the process. The creation, the fucking up, the sharing, the fulfilment, the learning.

Yet we are so sickened and diminished by this culture that we start to think someone offering "hey, I'll give you the product without the process" is a good deal!!

Wow, the conclusion without the reasoning — what could be better!?

Enter the engineers:

"YES!! not only will we take this away from you, we'll take it away from everyone! You'll forget it ever existed!!

Hey, we'll even get you safely to death without having to live at all."