Making Capitalism Bad Again

How ditching the cognitive dissonance of liberalism makes some men feel secure once more

Paying subscribers can listen to me reading this essay here (34 minutes)

When I left the financial sector in 2011, I began working on activist campaigns fighting for social and ecological justice. Upon seeing this, some people would call me a ‘reformed banker’. The phrase suggested that I once did ‘bad’, but was now trying to do ‘good’, having reformed myself.

This goodies-versus-baddies morality irritated me. In fact, rather than thinking of myself as a reformed banker, I thought of myself as a corrupted activist, a person who’d started out with a more black-and-white worldview, but who’d been shaded a mottled grey through deliberate exposure to the dark side (see my 2015 piece on Dark Side Anthropology).

I did, however, come to know people who thought of themselves as reformed bankers. Often they were individuals who’d grown up with conventional notions of professional success, and who’d gone into finance believing it was a respectable career path, but who’d later become disillusioned. Seeking something more meaningful, they’d pivoted to fields where they could use their skills for good.

The obvious path for many of them was to switch into the ‘finance for good’ space. This included the responsible investment sector, which used ESG (environmental, social and governance) metrics to make investment nicer. It included the natural capital community, who were trying to put prices onto the ‘ecosystem services’ offered by nature, so that those could be more readily valued within financial models that otherwise ignored them. There was also much buzz around climate finance, with innovations like ‘green bonds’ to steer money into low-carbon activities.

The field of social finance was also an option, with ‘social-impact bonds’ being pioneered to bring private sector investment into social work with teenage delinquents, or homelessness reduction, areas that traditionally yielded no profit for hard-nosed investors. Social finance got a boost in the UK around 2011 via the ‘Big Society’ agenda of the Conservative government, which wanted a reduction of state involvement in areas like community work and education, by replacing it with ‘social enterprise’ businesses who’d seek profit while doing good.

These scenes, however, were all politically coded as centrist. People involved in social and environmental finance were not anti-capitalists calling for the downfall of markets, or communists calling for state ownership of corporations, but they also weren’t cartoon banksters who’d smoke massive cigars and adorn themselves with gold-plated Rolexes and strippers.

Rather, like all centrist crews, they exuded a certain progressive sophistication, with clean modern venues for their events, and an assumption that you’d drink wine at dinner afterwards in an upmarket restaurant. This wasn’t the anarchist left, who’d gather in grungy squats, and it also wasn’t the old labour left, who’d gather in austere community halls. These were people who believed that capitalism could be good, if only we innovated it in that way.

This was, for want of a better term, the liberal world.

The nice face of capitalism

It’s common in the US for right-wingers to use the term ‘liberal’ to refer to anyone with any vague tendency towards anything that could be considered leftist, from hardcore Marxists who call for the overthrow of capitalism, to softcore entrepreneurs who call for gender-neutral bathrooms.

Actual liberalism, however, is a philosophy with multiple sides, because it originally just referred to a belief in the priority of the individual over the collective - otherwise known as ‘individual rights’ - along with an appeal to enlightened rationality.

In very crude terms, if old kings believed in traditional hierarchical conservativism, and the peasants were heading towards a belief in collectivist socialism, the urban capitalist classes might take on a liberal orientation.

Nowadays that orientation has a conservative version in libertarianism, which believes an individual capitalist should never be hounded by a mob of socialists, but it also has a left-ish ‘cultural liberalism’ version that believes an individual member of a minority should never be hounded by mobs of traditionalists (who’d otherwise beat up or bully people considered to be outsiders or weirdos).

These varied uses of the term make it particularly hard to use in argument, which is why people add prefixes to differentiate between versions of it - hence terms like ‘classical liberalism’ or ‘neoliberalism’, both of which are nowadays coded conservative, and ‘social liberalism’, which is considered more left wing (if you’d like to dive into the weeds of all this ambiguity, I’d encourage people to read Grace Blakeley’s recent piece Is Liberalism Really Dead).

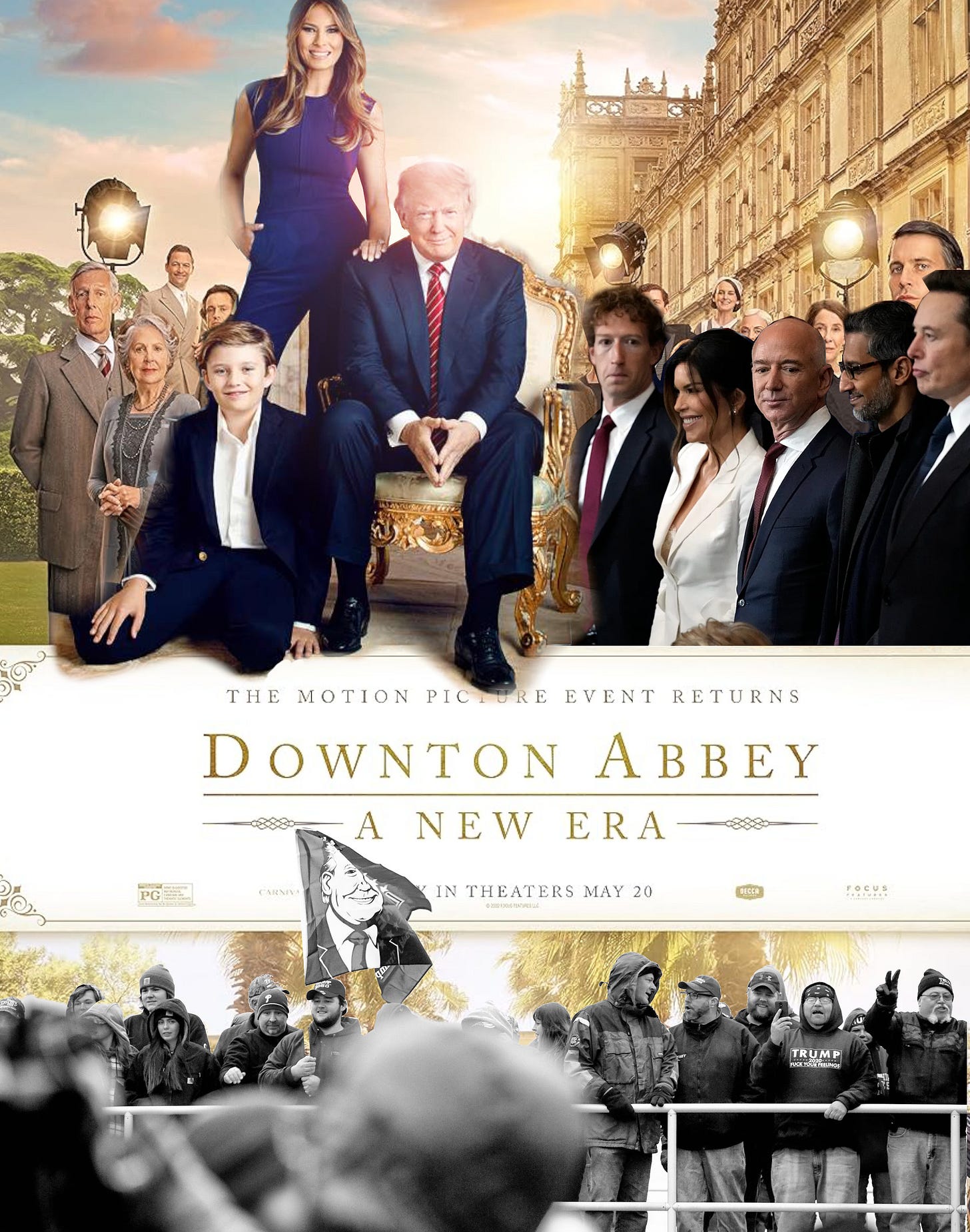

That said, what ‘liberalism’ often now refers to at the level of vibes, is a kind of surface-level niceness that most readily takes root in sub-sections of wealthier socio-economic classes. If you want to get a feel for this, watch the classic UK series Downton Abbey. In it, Lady Sybil Crawley is one of the daughters of the conservative lord of the manor. She’s a liberal reformer who wants to extend more rights to the early 20th century working man. That’s the kind of man that her father is happy to lord himself over. The first minute of this captures that family tension…

There’s a long tradition of such liberal reformism. For example, during the racist apartheid regime in my home country of South Africa, the figure of the white liberal tried to stand up for exploited black workers during the 1970s and 80s. White liberals, however, were often viewed with suspicion by black radicals, who saw their well-meaning niceness as cosmetic. After all, was the white liberal truly going to give up their nice house and swimming pool for the dispossessed masses? (For an amazing exploration of this, see Rian Malan’s 1990 book My Traitor’s Heart).

Indeed, in true hard left circles, liberals are generally considered to be a distraction that dilutes the power of working class movements. More militant radicals aren’t interested in Lady Sybil being nice. They’re interested in confiscating her family’s property to break their hold over society.

This is one reason why proper lefties often see liberalism as a component, or outcome, of capitalism, a kind of ideological facade that can take root within it. Political strategist James Schneider puts it neatly when he describes liberalism as capitalism when it’s feeling relaxed and secure. It’s the ‘nice’ face of capitalism that will entertain the idea of alleviating things, and which grants greater status to those capitalists who make gestures towards being philanthropic.

A quintessential marker of capitalism’s liberal face then, is that it often makes strong appeals to good intentions, and when this face is in vogue, the heroes are capitalists with a heart. The ultimate liberal business hero is someone like Bill Gates. He’s a billionaire, so he must have played capitalism hard, but he also perceives himself as moral and responsible, and wants to ‘give back’.

In many ways, though, Bill Gates is the essence of that airline safety mantra - put on your own mask before helping others. He gets rich through exploiting the rules of the market - scaling up and dominating - and then seeks to ‘do good’ afterwards. His model is ‘do well for yourself, and then do good’, but a variant of this is to do well by doing good. Here, for example, is MasterCard imagining itself as a ‘good corporate citizen’.

The ‘doing well by doing good’ mantra is loved by corporate social responsibility officers, even if it’s always been marginal within capitalism itself. This ethos of trying to harmonise profit-seeking with areas traditionally neglected or screwed by profit-seekers turns up in phrases like ‘stakeholder capitalism’, ‘inclusive capitalism’, ‘compassionate capitalism’, and ‘sustainable capitalism’.

The dissonance of niceness in a harsh world

The liberal face of capitalism is inherently confusing. That’s because - when push comes to shove - capitalism isn’t inclusive, compassionate or sustainable.

I don’t say this sanctimoniously. It’s just a reality that we live in a fundamentally insecure economic structure, and that fundamental insecurity simply isn’t compatible with fundamental inclusion, compassion and sustainability.

For example, as a child grows up in a capitalist economy, they’ll become aware that, sometime in the future, they’ll have to fight for a place within a vast, fluid job market that’s almost impossible to predict or understand. They see giant firms, and realise that they’ll have to suck up to people in positions of hierarchy to try to get in.

Even if they, and you, get a place, it’s never secure or guaranteed. You’re probably going to spend an entire life in a state of constant competition against others, during which time you may or may not have secure housing or healthcare. You’ll be told to constantly upgrade as new waves of technology come swooping in like hurricanes, and you’ll be told that you’ll be ‘left behind’ if you fail to keep up.

In fact, the only way to secure yourself is to try to beat others down and accumulate ownership of stuff, and then use that power and ownership to get more power and ownership. That’s what ‘winning market share’ means.

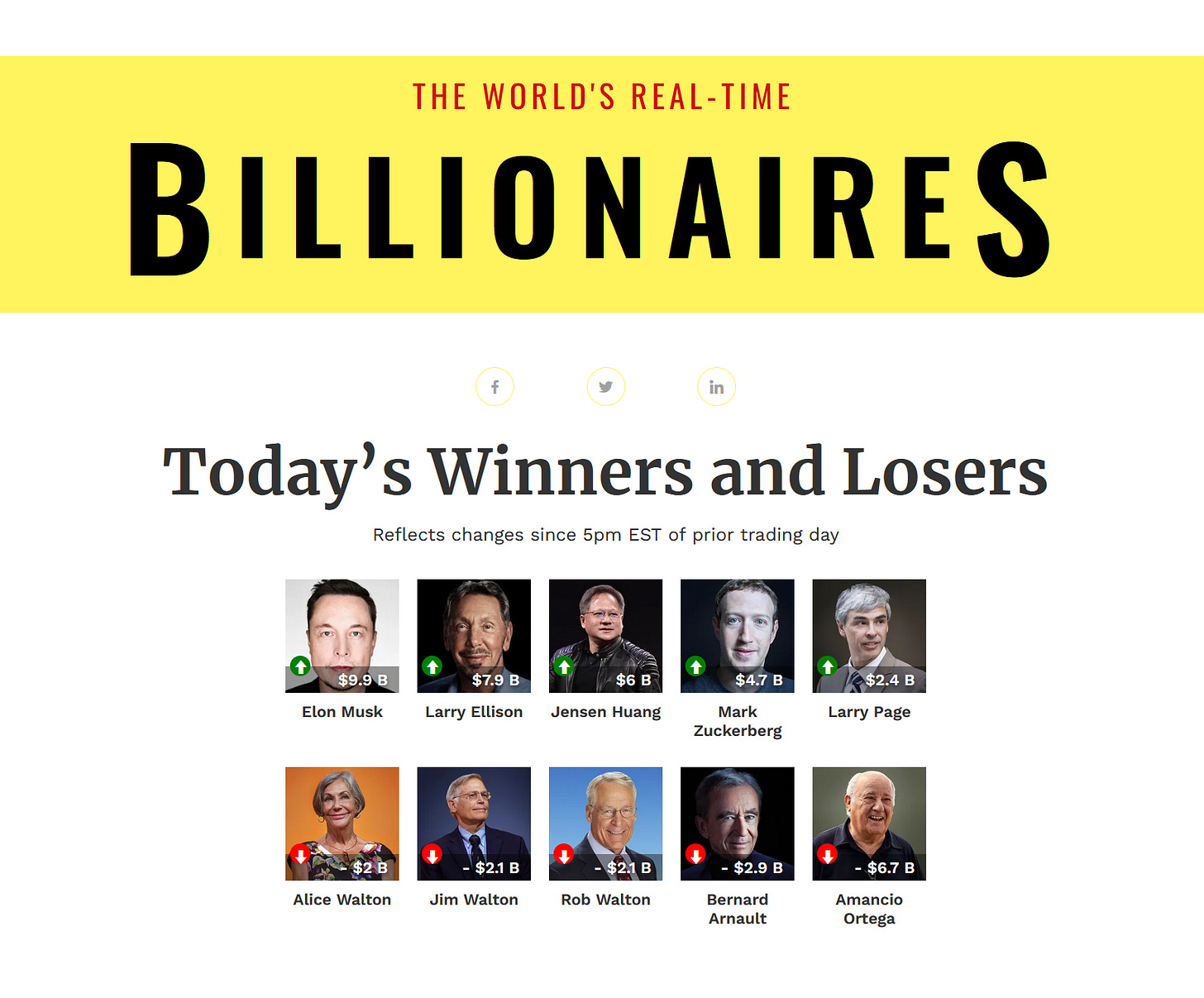

We don’t call our economic system ‘marketism’, or ‘tradeism’. We call it capitalism, in reference to that process of capitalizing on previous power to get more. This is the reason we have god-like billionaires and transnational corporations that are more powerful than entire countries. It’s not really because these players are hard-working or skilled - there are many hard-working and skilled people who struggle in our system - but rather because they know how to play the capitalist game, how to exploit their position, and how to work the financial sector. Rather than pushing hard work and skill into caring for the sick, they’ve pushed their entire selves into the competitive struggle for power.

This scramble is presented as a virtue in standard capitalist ideology. You’re supposed to take life by the balls, compete your way to the top, tread on other people, take advantage of gaps where others are too slow, and so on. The biggest official heroes in our society are those who have done that. We fawn over a class of people who have leaned into somewhat sociopathic traits, but they are seen as inspiring and innovative go-getters.

In the end, the message is always the same: elbow other people out of the way, forget the long-term meaninglessness of this, and focus on accumulation. Scale it up. Outcompete. Monopolise control. Secure your legacy into eternity.

Unlike a hunter-gatherer group, where an individual member starving would be seen as a collective failure, official capitalist ideology tells you that a person struggling on the street has got nothing directly to do with you, because you don’t really live in ‘a society’. You’re just an individual, free of attachment.

In fact, in the harshest versions of the ideology, it’s assumed that everyone who gets ‘left behind’ deserves it, because they’re lazy, or weak, or stupid, or an inferior race, or not good at playing the game. The struggling person is someone who refuses to take responsibility for their life, and so deserves to live in poverty.

That’s the deep message in capitalism, but this harsh story coexists with the liberal alleviation narrative, which tries to say that this fundamentally extractive and competitive system can somehow also be a fundamentally life-sustaining and cooperative one.

Liberalism is like capitalism with a left-tinted mask on. Rather than shunning the ‘losers’ of society, it prefers to cast these unfortunates as not being on a level playing field, or needing certain forms of assistance or compassion. If we can have a fair market, everyone will get a fair chance and capitalism will be inclusive.

I totally understand why this story is appealing to people who are working corporate jobs that otherwise might feel soul-destroying, but in trying to merge ‘doing well’ with ‘doing good’, capitalism’s liberal mask sends out a contradictory message.

On the one hand, it keeps that basic capitalist story. You’re still supposed to do well for yourself, pursuing your desires over others, competing against them in the market, and growing your empire. In other words, you’re still supposed to behave like an arsehole.

On the other hand, you’re told to be a good person. You’re supposed to care about those you compete against. You’re supposed to care about the unemployed, the homeless, the environment, and the climate.

Projecting those two messages simultaneously into society causes cognitive dissonance. It’s like telling a young child that they’re loved, but only if they perform contradictory tasks, like being a good boy and a bad boy at the same time. That would leave a child with a pervasive sense of confusion, and a constant sense that they might actually lose the love by failing to complete the incompatible tasks. In this case they’re haunted by a constant sense of impending guilt.

This feeling is very common in liberal circles. For example, a middle-class person in London is well aware that our economy is eating the world’s resources, and that they - like everyone else - is complicit in that as they stand in the supermarket with their plastic-wrapped meal. So, they go through the motions of recycling their rubbish, believing that their failure to do that might somehow be the cause of our system’s unsustainability.

Perhaps they also feel that individual acts of buying ethically-sourced fair trade clothing will override the much more powerful systemic imperative to cut costs - which inherently favours sweatshop labour (or automation) - even as they’re constantly surrounded by messaging that tells them that cutting costs and getting cheap goods is great.

This feeling of being told to be a dickhead and not a dickhead at the same time makes you feel like a guilty failure. So, in situations where the liberal face of capitalism gets mainstreamed, and projected widely, more people are exposed to this sense of guilt. Get the cheap goods from Amazon, and also care about struggling workers. Go on this cut-price holiday, but make sure to offset your carbon. Undercut your business opponents so that they have to fire their staff, but also donate to charity.

It’s a dissonance that can get projected at the highest levels of society. For example, the government promotes its plans to boost competition and growth, while unveiling a separate plan to reduce carbon emissions that naturally emerge from such growth. The minister turns up at the World Economic Forum in Davos to have cocktails with business moguls enriched by exploitation of workers, and then sits down to speak on that panel about inclusive capitalism.

Square, or circle

When I occasionally used to hang around the responsible investment, natural capital, and social finance scenes around 2012-2015, they were incredibly marginal. The mainstream financial sector didn’t give a toss about ESG in their actual operations, and were continuing to fund oil, coal and oligarchs that collaborated with violent dictators.

ESG, though, was a talking point among the refined in society. It did seem nice, and it could be displayed by big firms as something they were thinking about. They’d often stick it on their corporate social responsibility (CSR) website page, even though almost none of their revenues came from that.

These alleviation stories always had that appeal to good intentions. It would be nice to have more diversity in our staff. It would be nice to have a non-destructive supply chain. It would be nice to not slowly poison our customers. As Coca Cola’s plastic bottles clogged up the world’s oceans, the company would tell us that it would be nice if we lived in a world of idyllic sustainable greenery.

De facto, ESG has mostly always just been a kind of performative charade, but one that was useful to act out in an age where there was legitimate and growing concern about climate change and inequality. It was the kind of thing that Oprah Winfrey might showcase, a feel good story about how you could carry on living your middle class life while being a good person.

This appeal to good intentions is deeply problematic, because it introduces an impossible ideal into your head. It tells you that we can square a circle, and that doing so is hopeful and progressive. In doing so, however, it also creates a pervasive sense that you’re failing to fulfil that, because - after all - a square isn’t a circle.

This guilt at failure can turn into a simmering, low-level anger at yourself, so how do we deal with this cognitive dissonance?

Well, one common path is to simply disassociate and not think about it. Another is to put on a brave optimistic face, and stick your head in the sand, telling yourself that a world of square circles is totally possible, and totally not magical thinking.

Alternatively, you can take a more meta, quasi-Buddhist path, and accept the fact that we live in a contradictory reality, and that life always calls for square circles no matter what system you live in.

The more obvious impulse, though, is to escape the dissonance. For example, you could try to detach from the situation. This is what people who ‘go off grid’ do. They don’t want to face the contradictions of life under capitalism, so tap out to create small, semi-detached enclaves for themselves in the countryside, or as a nomad in a van.

That’s not a viable path for the vast majority of people though, so another obvious way to escape the dissonance is to simply side with the square and drop the circle, or vice versa. For example, you can become a hard left agitator, rejecting consumerism and dedicating your life to forming authentic counter-power to capitalism, by unionizing workers or fighting privatisation and austerity.

Alternatively, you can lean in hard on your consumer capitalist side, and make a virtue out of being a ‘bad boy’.

Drill, bad boy, drill

In sociology, Labelling Theory notes that if you continually tell someone that they’re bad, one response is for them to co-opt that label as their identity. Rather than denying it, they turn around and say, ‘yes, I am bad’.

This latter path is perhaps best captured by Trump’s now famous use of the phrase ‘drill, baby, drill’. In using it he offered an escape from liberal capitalism’s cognitive dissonance. He was accepting the label of bad boy, and giving an official endorsement that you didn’t have to care about one side of the contradiction any more.

This goes a long way to making sense of that visible euphoria that accompanied the Trump campaign, that elation at putting the middle finger up to ‘liberal’ concerns. We don’t have to care any more.

So, rather than a person being angry with themselves for failing to square the circle, they turn that towards whoever they imagine has set out that impossible requirement. It makes sense then, that rage gets directed towards an imagined ‘liberal elite’, characterised by inconsistency, flip-flopping, masks, and square-circle hypocrisy. It’s no coincidence, for example, that Bill Gates and ESG have been heavily targeted by the new right.

There are of course elite interests at play in that attack - the oil industry, for example, hates ESG, and Big Tech needs shit-tonnes of dirty power to run its AIs - but there’s also a grass-roots desire to step into the badness.

To a person invested into the liberal capitalist worldview, this virulent popular attack comes across as callous. Why does a Trump supporter cheer hysterically at ‘drill baby drill’? Do they hate the environment?

I can’t speak for the deep Trump base, but I’m guessing that for many newcomers to the campaign, the euphoria at badness doesn’t come from hating the environment, so much as it comes from that feeling of release from contradiction, and the simplification of life that it brings.

To people in the ESG community, this attack is quite shocking. Much like the transgender community is a tiny minority that gets outsized levels of hate, ESG (with its ‘reformed bankers’) is a tiny minority in capitalism that has almost no power within the actual financial sector. The imagination of its power comes from the fact that corporations pasted ESG over their websites and PR statements while ignoring it, just like they pasted the rainbow flag over themselves.

Those acts of pasting created that illusion of what the Trump campaign called ‘woke capitalism’, but that’s just normal capitalism with its liberal mask on. Corporations wore that mask for little more than a decade, but in wearing it they told everyone who was subjected to their announcements and adverts (aka. the whole world) that they should be wearing it too.

Now, tearing that mask off is experienced in euphoric terms, with the thrill of transgression, like that child accepting their bad boy persona.

Badness as the ‘warrior ethos’

Here, however, is a complexity. Even if people feel a desire to take on the bad boy label, they still want to believe it’s a good path, rather than a weak cop-out. In psychology, they might call this ‘ego defence’, the processes you go through to tell yourself that you’re in the right.

For example, a person cheering at ‘drill baby drill’ is well aware that their rejection of conservation looks bad. After all, what human group in history would ever believe it to be good to destroy their own environment? That’s just stupid.

So, to escape the liberal capitalist dissonance while protecting their egos, they might be attracted to stories that cast ESG as a vile plot by elites to subjugate humans, rather than something that ‘does good’. This allows them to feel like they’re fighting some greater evil, rather than just being evil themselves.

More generally, they protect the ego by framing the bad-boy persona as a series of positive values, such as strength, competition, vigour, and innovation, all of which are imagined to have been suppressed, or denied, while wearing the mask.

Indeed, the tearing off of the mask is accompanied by an imagination of taking up arms again, or adorning the helmet of the warrior once more.

A good example of this was Marc Andreessen’s 2023 Techno-Optimist Manifesto, in which he - the world’s most powerful venture capitalist - imagines that capitalism has been terribly emasculated by woke pessimists who are holding back the potency of the market, noting that:

Our present society has been subjected to a mass demoralization campaign for six decades – against technology and against life – under varying names like “existential risk”, “sustainability”, “ESG”, “Sustainable Development Goals”, “social responsibility”, “stakeholder capitalism”, “Precautionary Principle”, “trust and safety”, “tech ethics”, “risk management”, “de-growth”, “the limits of growth”.

He goes on to claim that technology and capitalism create an “engine of perpetual material creation, growth, and abundance”, which “never ends” as it “spirals continuously upward”, serving human wants and needs which are “endless”, and that this continues in spite of “continuous howling from Communists and Luddites”.

At the risk of being crude, Marc’s Manifesto is like a thrusting dick, throbbing with excitement at leaving behind stupid concerns about fairness, equality and sustainability. This same impulse circulates within the ‘manosphere’, in which environmentalism is presented as an attack on masculinity, a requirement to care, conserve and hold back when your job is to dominate, thrust and move forward.

This isn’t new. In 2010 I gatecrashed the London launch event of an architectural manifesto called MANTOWNHUMAN. It was a bunch of middle-aged male architects who were complaining that sustainability was emasculating their profession. They were being prevented from digging into the earth with their bold futurist designs. Their complaint foreshadowed Marc Andreessen. They moaned that:

Nowadays 'architecture' and 'design' are regularly prefixed with words like 'inclusive', 'participatory', 'community-centred', 'sustainable', 'ethical', 'ecological', 'efficient', 'carbon-neutral', 'socially-engaging' or 'environmentally-responsible'… Why has the mere act of designing taken on such a moralistic mantle?

Their manifesto, like Marc’s, called for a form of design that was bold and brazen enough to not care about ‘virtue signalling’. In fact, they were going out of their way to do vice signalling, naming themselves as champions of ‘socially irresponsible design’.

The disgruntled men of ‘Mantown’ were, back in 2010, already signalling that the contradiction in capitalism’s liberal face weighed most heavily on men, who might have the greatest desire to escape it. After all, they’re historically the ones most heavily force-fed the competitive side of the capitalist story (and also the ones who stand to lose the most from forms of alleviation).

In fact, such men might look upon people like Sheryl Sandberg, Oprah Winfrey and Kamala Harris as their nemesis: business-oriented women who also insisted on niceness or other ‘feminine’ values.

This association between liberal capitalism and ‘femininity’ means they might fantasise an escape that involves a turn towards a cliched macho-ness. We see this in the words of US defence secretary Pete Hegseth when, in 2025, he said “We are leaving wokeness and weakness behind”, in favour of a “warrior ethos”. As Hegseth seeks to rename the defence department to the Department of War, it’s a metaphor for the economic system too: you’re a soldier in the war of the market, so forget the Geneva Convention, and get out there and fight. Commit atrocities if you have to.

Conclusion: The contradictions of honesty

It’s a common refrain for people to say that Trump is ‘honest’, but that’s because he’s not attempting to square the circle. He tells you to play hard, eat red meat and drive gas-guzzling cars, because - let’s face it - you’re implicitly told to do that even within liberal capitalism, so just drop the facade.

Nevertheless, in leaning into this ‘honesty’, Trump also creates contradictions of his own. For example, he tells people that capitalism is a system that is supposed to reward the most hard-working and the most innovative, but he also insists that its existing elites are part of a ‘swamp’ that uses a corrupt ‘deep state’ to subvert the fair rules of the market.

This story involves whitewashing the actual historical reality of capitalism, which has always been underpinned by states, law-fare and cronyism. Capitalism developed out of feudalism - the remains of which are showcased in Downton Abbey - and never once in history has it begun with a ‘level playing field’. It’s always been a system that favours people who start off with more capital and political connections, and are able to capitalize on that, just like Trump himself.

What’s fascinating, and kinda horrifying, to outside observers, is that Trump so blatantly follows the cronyistic model that it must surely require a new form of cognitive dissonance on the part of his followers to not see that.

Indeed, there’s something very kludgy in the Trump narrative. It’s like he spotted an opportunity to unite people against a common enemy - the dissonant ‘liberal establishment’ - but cannot fully disentangle himself from accusations that he’s tainted by hypocrisy himself (hence his desperate efforts to distance himself from Epstein).

The bad boy label can, however, help him here again. The ‘establishment’ does bad while claiming to be good - which is ‘swampy’ - which means honesty might entail showcasing the sludge that surrounds yourself. When Trump openly screws his supporters by selling them his memecoin, or enriches his friends and family via nepotism, he’s leading by example - like a general in the war of capitalism - showing his followers that it’s a dickish system that you have to behave like a dick within, and that you’re a weakling loser if you don’t do it.

In fact, at face value it actually looks more like Trump is attempting to ‘democratize’ the swamp, to spread it more widely, rather than draining it.

That, however, would be a generous interpretation. When you push past Trump’s apparent promotion of some populist ‘bottom-up’ capitalism-of-the-people, you’ll see that - in the background - what’s truly emerging is a new picture of Downton Abbey.

In this picture, we have loyal billionaires taking their place as lords. They embrace their position in the hierarchy, having no embarrassment at it, and demanding respect. Such swagger, though, is imagined to be inspiring to the servants downstairs, who imagine that they too can be the lord if only they pursue it hard and dirty enough, and push each other out the way.

One thing everyone can agree upon is that they hate the liberal reformer Lady Sybil. She’s telling the servants that they’re unfortunate, when they want to believe that they too can be Elon, or Larry Ellison, or Andreessen, or the Winkelvoss Twins.

Above all, this is a vision of respect for hierarchy. The populist movement isn’t interested in Bill Gates saying that he feels sorry for the bottom billion. Rather, all that matters is focusing on trying to better your immediate self and your immediate family by staying on the winning team, which rightfully holds a higher place over others.

At the simplest scale you’re supposed to be a hard working entrepreneur fighting for Team You, but you do so because you’re also a family man protecting Team Family, and a proud patriot flying the flag for Team Country, which succeeds by crusading for Team God. Those teams are nested within each other like a Russian doll, and your morality within this framework emerges from how hard you fight for each.

In many ways, this is just a restatement of old school conservativism. We’re back to the 1950s, and all you have to do is be a good unquestioning patriot fighting the godless commies, protecting your family, and winning in the (sorta) ‘free market’, while believing that you too can be a billionaire. You’re free from disloyal thoughts and un-American doubt. You don’t have to be embarrassed about clawing for status by driving your big car and eating your big steak and yelling at homeless people to get a job.

James Schneider notes that people like Bill Gates want to present themselves as champions against the rise of this new gold-plated illiberalism, but in many ways the former is just a different face of the latter.

As James notes, fascisty or thuggish vibes emerge when capitalism is feeling insecure and anxious. That’s when the systemic forces within it will - through thousands of degrees of interconnection - come to favour leaders who batten down the hatches and get people to lean into the more authoritarian parts of their personality. That involves de-prioritizing experimental free-form thought, and making it more rigid.

The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought characterises the ‘authoritarian personality’ as follows:

A personality type characterized by extreme obedience and unquestioning respect for authority. These defining characteristics are usually accompanied by rigidity, conventionality, prejudice and intolerance of weakness or ambiguity

This is the aura of a character like Biff Tannen in the 1985 film Back to the Future. He’s a douchebag bully who insults weirdos on the street while thinking of himself as an alpha man among men who doesn’t like contradiction, or wishy-washy, unpatriotic, deviant liberals.

Good for Biff, but in the end capitalism doesn’t really care about him either. All it cares about is accumulation, and if turning people into Biff is what’s required to do that at the current moment, then so be it.

I personally find Biff inauthentic, unimaginative, underwhelming and un-embracing of the diversity and weirdness of the human spirit. He’s a character full of fear, masking his insecurity with outward brazeness, like a person who puts a straight jacket over their own soul to protect themselves.

I feel sorry for Biff, but - more than that - I feel sorry for everyone he will harm. That’s why I will fight him.

Holy smokes, you must have been chewing on these ideas for a while.. this was fantastic!

Not sure if intentional (I suspect so) but you really trojan horse some of the strongest ideas into this piece the way it's structured.

I think even some of my Biff-like acquaintances may nod most of the way through it before their brows subtly furrow and confusing feelings bubble within 🥲

Good essay. Thanks. I love James Schneider's concept of the two personalities of capitalism and their relative dominance being reflective of the security of capitalism's status quo. I hadn’t heard that before. The release of cognitive dissonance in the rejection of ESG also rings true.

I'm hoping for an additional exploration of the flipside.

By the flipside I mean the release of cognitive dissonance the ESG crowd feels when it finally stops trying to reform capitalism and ditches it completely. How do we ditch capitalism? How do you proceed when you've already ditched your belief in capitalism but most activism truly does look like virtue signaling? How do you proceed when you understand the appeal of patriotism, nationalism, family, and church – after all, the only clear means of security is a paying job in the national economy, and family and church offer much needed belonging – but you're surrounded by Lady Sybil types who think those wrong-headed 1950s people are the problem? How do you ditch capitalism when the entire international structure encloses people into nation-states that define citizens as producers in a global capitalist economy? How do you ditch capitalism when culture itself is enclosed by a global system of compulsory schooling that replicates competitive capitalist culture, yet everyone around you who complains about capitalism reveres universal schooling?

Too big an ask, I know. You’re doing a lot by offering tools of explanation. I guess that’s one answer to “How do you proceed?”

On second thought, I just realized that the question I’m trying to ask is this: How do we create an alternate source of security? I’m unconvinced that activism and union support can resolve the underlying insecurity that capitalism thrives on. I know unions can be helpful, but I’m not all in. I think I’m struggling with the false dichotomy between the individual and the collective. Capitalism doesn’t care about Individual freedom. Capitalism steals freedom. Capitalism crushes individuals. Autonomous individuals are naturally motivated to find community. I’m tired of leftists targeting individual liberty as the enemy. It’s both false and counterproductive. It’s like we keep insisting that “9 out of 10 workers agree, autonomous individuals prefer capitalism!” It’s a pretty shitty sales pitch. I want individual liberty back. We don’t have to sacrifice the rights of individuals for the sake of collectives. We need freedom from capitalist constraints to regain our autonomy so we can fulfil our inherent desire for collective belonging.

That’s what most of us are looking for: security in belonging. I’m also convinced that our fucked-up concept of education pulls that out from under us before we have any chance of becoming something other than capitalist cogs.

I hope this doesn’t come across as criticism. I love your essays and videos. I’m just searching for something I haven’t found.