Remastering Capitalism

If our economic system were an album, it would sound helluva distorted

Paying subscribers can find the audio version here

I’ve played instruments since I was eight, but it’s only in the last year that I’ve been teaching myself how to mix tracks. The history of recorded music is pretty fascinating, and one of its breakthrough technologies was the multi-track tape recorder. For example, a 4-track recorder enabled a musician or band to record four different tracks in parallel, set each to its own level, and then output them as a single master track. Bruce Springsteen’s 1982 Nebraska album was recorded on 4-track, giving it that lo-fi sparse sound.

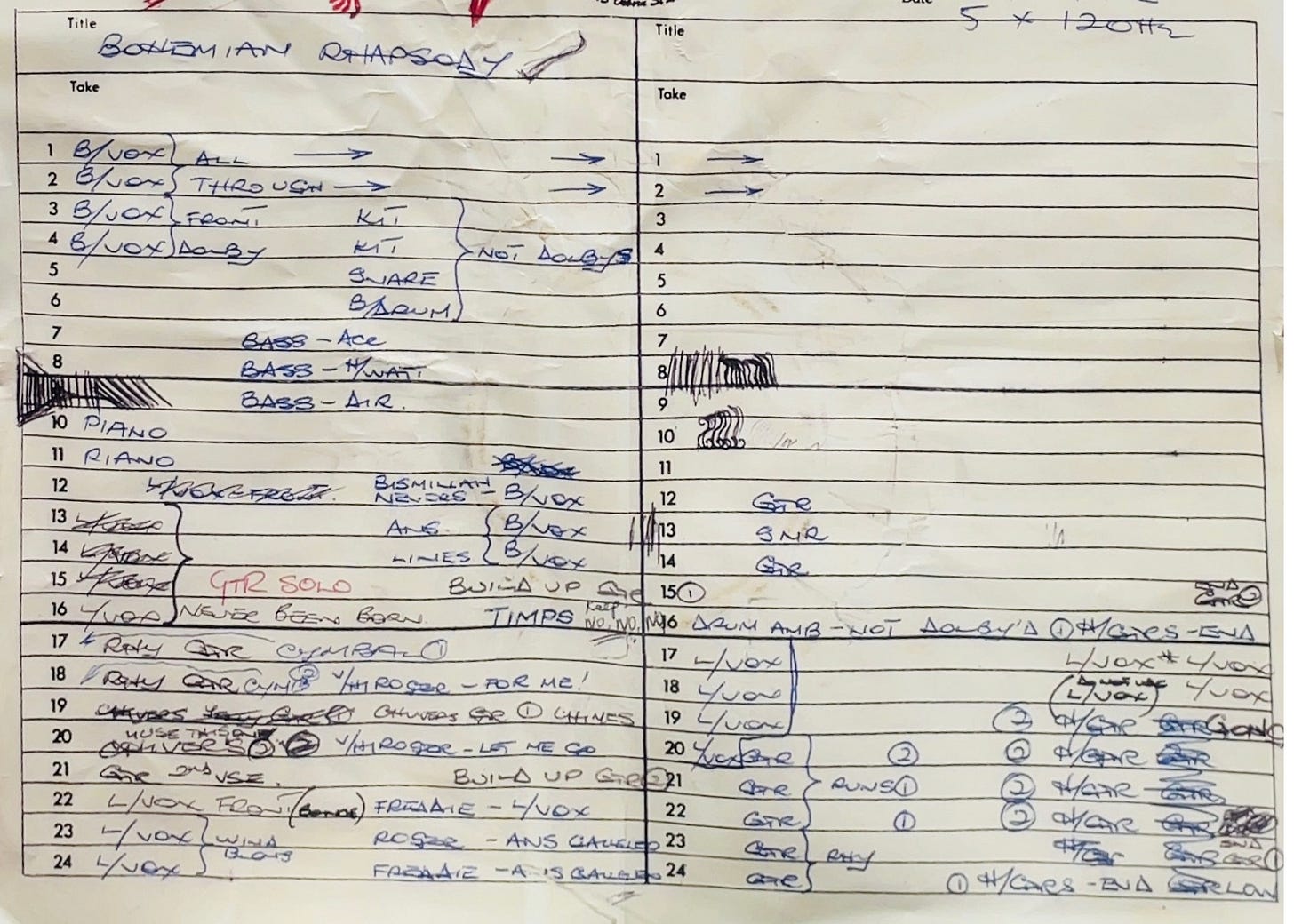

A more complex song like Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody, by contrast, used a 24-track system, allowing for all those layered harmonies. Here’s a breakdown of the track structure…

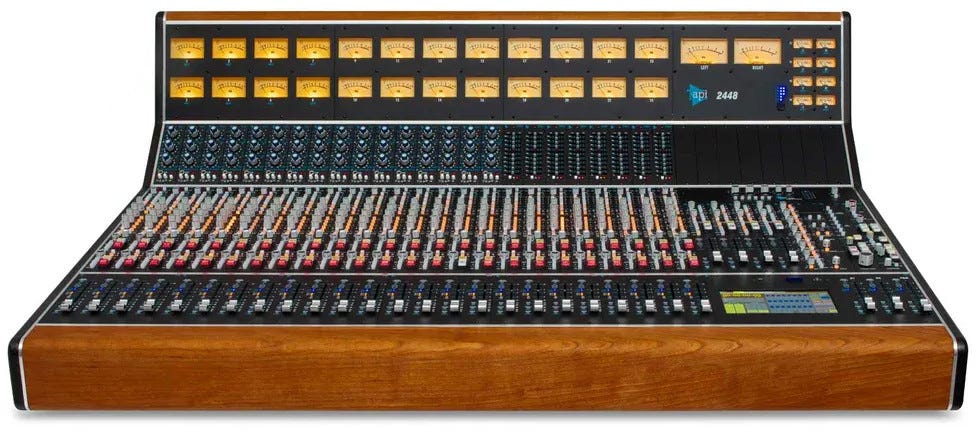

Each of those tracks was separately recorded, but you can’t just squash them all into a big bundle and hope they all sound good together. To make the song shine, you have to mix the separate tracks, so that they complement each other to create a symbiotic whole that’s greater than the sum of the parts. Nowadays most people use digital programmes (like Ableton and Pro Tools) for mixing, but in Queen’s case they would have used a 24-track mixing console. Here’s a modern version.

This console looks very complex, but if you count from the left, you’ll find there are 24 vertical strips of identical knobs, with each strip dedicated to a track. These allow you to adjust the parameters of each track - how loud it is, the balance between bass, treble and mid frequencies, and the stereo panning - before sending them to the right side of the board to get compiled into a master track which can then be tweaked with finishing touches, or mastered. So, in 2011, when Queen released a ‘remastered’ version of Bohemian Rhapsody, it means they took the original mix, but re-polished the master.

So, what does this have to do with capitalism?

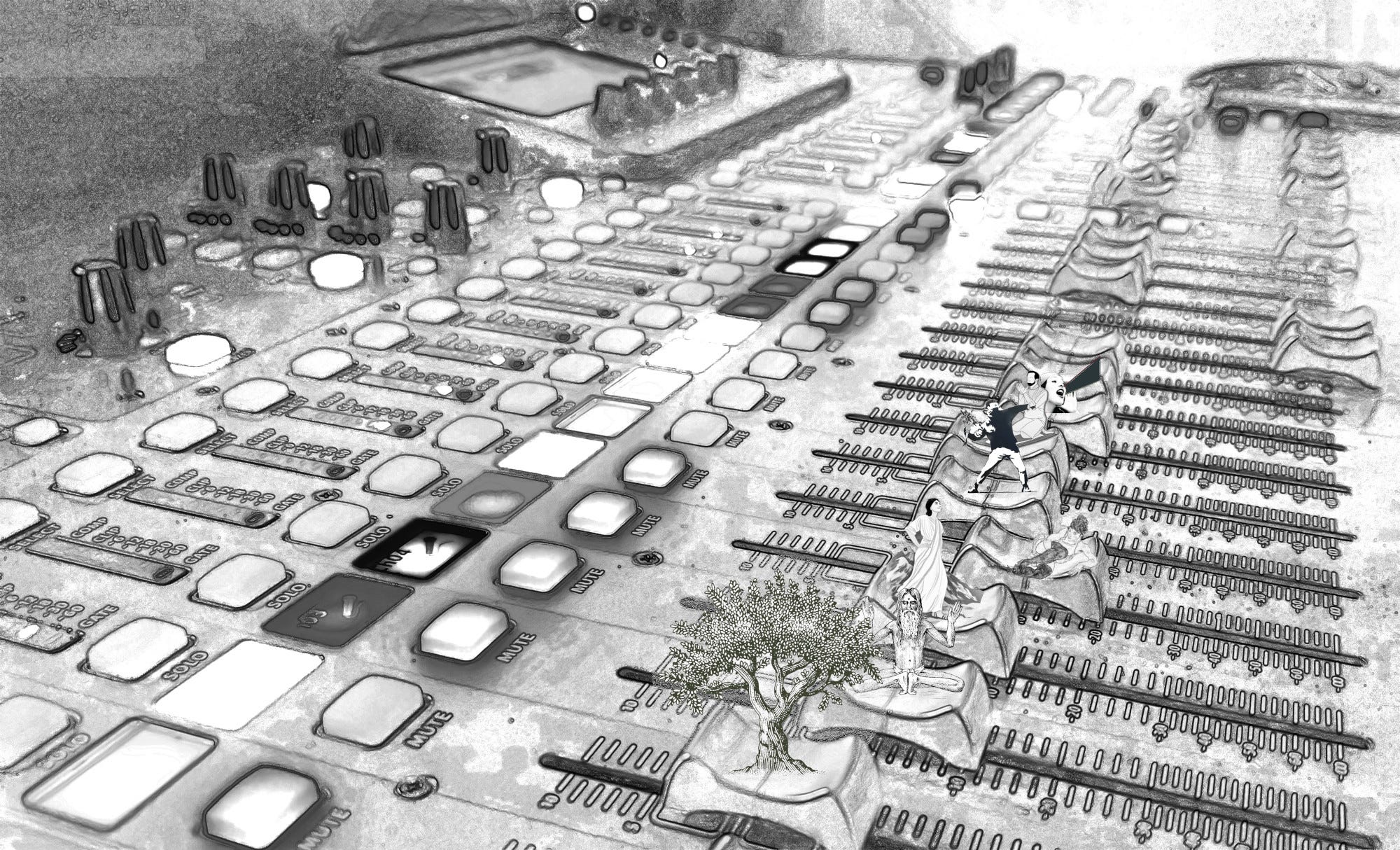

Mixing and mastering are art-forms dedicated to bringing separate things into a whole, and this provides us with a new metaphor for thinking about how our economic system brings together different parts of our being. When listening to a song, we experience it as a whole, and we seldom think about the many alternative ways it could have been mixed. Similarly, each of us experiences ourselves as a whole as we navigate corporate capitalism, but we seldom think about the many alternative ways we could have turned out if we were living under a different system. The system we’re in will amplify certain values, beliefs or ‘natures’ within us, while filtering others out.

This is a theme that I’ve been exploring in other pieces too, using different metaphors. For example, in my piece Socializing Homo Economicus, I noted that economists often fixate upon one particular view of human nature called ‘Homo Economicus’, which was popularized from the 18th century onwards. Economists noticed that we have an accumulative and a competitive streak, but rather than seeing that as but one element of our being, they fixated and zoomed in on it, presenting it as our defining feature. They created a world-view in which

… all humans are solo ‘agents’ out for themselves. We are presented as ‘rational’ and narrowly self-interested, always wanting to maximize - to accumulate more - as well as to optimize and seek efficiency to reduce loss. In the Homo Economicus model, we are calculating machines weighing up costs and benefits, pros and cons, to our individual selves.

In that essay, I used the metaphor of a prism to help break us out of the economist view. Just like a beam of light contains multiple spectral wavelengths that can be seen by passing it through a prism, so Homo Sapiens contains multiple ‘human natures’, of which Homo Economicus is but one.

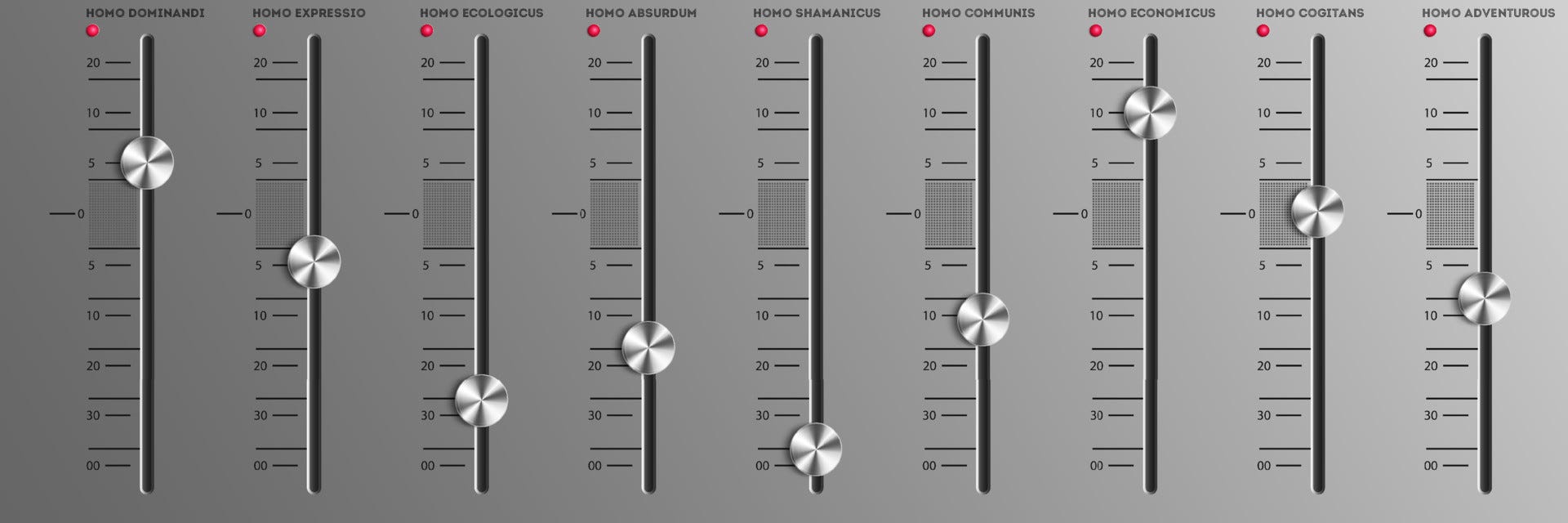

This gives rise to the question of what our other natures are. There’s no perfect way to answer this, but I went on to give examples of many other possible ‘natures’ within us, which come together to form our full selves. Homo Economicus is still in there, but it has to coexist with these others, sometimes in contradiction and sometimes in harmony.

I expand upon these natures in the aforementioned piece, but, as an example, I describe Homo Absurdum as that part of us that loves playing jokes and being silly, and Homo Ecologicus as that part that feels awe at the natural world and wants to stare at the moon. Homo Meditari is that part of us that seeks stillness and emptiness, while Homo Cogitans is that part driven to understand the world, to build theories and thought structures. Homo Communis is that part of you that wants to be cuddled, while Homo Dominandi is that part of you that seeks to control.

You can invent your own names for the different parts of your being, but the main point here is that we contain multitudes, and there are different ways to label them. That said, we don’t experience ourselves as separate pieces, but rather as a single whole, a continuum with fluctuations, ebbs and flows of our different spirits, and we don’t always know which parts of our being are calling the shots.

In the prism metaphor, those different parts have different wavelengths, but come together to form a single beam, but this opened the question of whether our current economic system might amplify, or filter out, particular parts of our inner spectrum.

So, let’s approach this question by doing a metaphoric pivot. Rather than imagining our different parts as different colours of the light spectrum, let’s imagine them as different tracks on a multi-track recorder, coming together to form the final master track which we call ourselves.

Mixing, and mastering, the self under capitalism

Before we explore this metaphor further, let’s clear some definitional hurdles. When I say ‘capitalism’, I don’t mean commerce, or trade. I come from an anthropology background, and within that discipline we’re well aware that forms of human commerce extend back tens of thousands of years. Tit-for-tat reciprocal exchange has always been one element of how goods are distributed in human society, but that has always coexisted with other modes of distribution, such as communistic sharing and hierarchical patronage. What marks out different moments in economic history is the balance of power between those different moral logics, and the hybrid blends they form.

For example, during the early medieval period you certainly find commerce and trade, but the central organising logic of the society revolves around caste systems that operate through patronage and tribute. The medieval market is found on the periphery of the society, rather than the centre, and if you were to partake in one of those markets you’d find the relationships within them to be far more fixed, and the movements of goods and their prices to be far more governed by tradition and convention than what you’re used to.

‘Capitalism’ is the name given to the situation in which all that begins to liquefy. For example, feudal peasants, who were previously fixed to the land, begin to drift and transform into an urban working class that must sell their labour to powerful owners of factories and technology, who can cut them adrift at a moment’s notice, or move somewhere else.

There are various historical factors behind this - including the rise of private property systems protected by large states - but the important point is that what we call ‘capitalism’ isn’t merely the presence of market trading or exchange. It’s the particular historical situation in which markets move from the outskirts of human activity to the centre. This means the values associated with market trading slowly begin to dominate over all other aspects of society. Once that process hits a certain threshold, the market centre of society starts to become like a vortex, sucking everything in as commodities to be traded.

In the 19th century that commodification might look like forests being reduced to logs which are sucked into industrial zones to be transformed into planks that get sucked deeper into the vortex to form the desk of a merchant, who is importing goods from plantations into which human beings are being sucked from West Africa as commodified slaves.

The market vortex has of course shifted its appearance over time - and it’s always fascinating to see its latest incarnation - but its basic processes, such as commodification, dislocation, liquification, and accumulation continue.

Its official ideology also stays relatively constant. The story, especially as told by the elites of the system, is that capitalism is like a big version of the old homely farmers markets, a realm of tit-for-tat commerce between mom-and-pop entrepreneurs. In reality, the system is rife with inequalities. It retains - and even amplifies - many elements of the hierarchical feudalism it grew out of. To see this just look at the corporations, those vast entities that cluster at the centre of the system, and which loom over us constantly.

We’re born into this (see Coming of Age in Corporate Capitalism), and this way of being is now so deeply ingrained in us that we can barely imagine anything else, but how does this affect the balance of ‘tracks’ within us? If we were to imagine ourselves as a composition, how would we differ from, say, an ancient Indonesian hunter-gather, or a 12th century Kazakh tribal pastoralist, or a 15th century Portuguese feudal tenant?

We might have an individual self, but there are systemic constraints that limit how much of that self we can express, or place conditions for how our different elements are to be expressed if they are to survive. Let’s turn to our mixing desk metaphor, and explore three different approaches for how a capitalist system affects our being.

Approach 1: Capitalism adjusts the mix

Life under capitalism amplifies certain tracks within you, such as your inner Homo Economicus. When 19th and 20th century economists started speaking about people as self-interested calculating machines, they imagined they were describing a universal and timeless reality. They tried to use that to explain the presence of markets, but - as Erich Fromm notes in To Have or To Be - traits like heightened egotism and selfishness are outcomes of that society, not causes of it. In reality, economists were simply noticing an aspect of human nature that starts to bloom when people find themselves totally immersed in - and dependent on - the insecure and fluid flux of a market vortex.

There are different mechanisms via which this may happen. On the one hand, within a large-scale market structure, certain groups get rewarded for leaning into their self-interested and calculating sides, and to place positive values on those. For example, I used to work in the financial sector, where many people would become ideologically attached to their Homo Economicus and Homo Dominandi tracks. They would over-identify with those, wearing them like a badge, even though they had many other aspects to their being. The film Wall Street is supposed to be a cautionary tale about ruthless financial warlords, but I distinctly recall it being held up as a kind of heroic ideal in the financial workplace. I even remember the first time I acted that out, shouting at a rival broker over the phone, telling him to get fucked. There was a strange exhilaration at letting this arsehole side of me emerge in that setting.

In the financial sector, the Homo Economicus track dominates, but that doesn’t mean the other tracks aren’t present in the background. While many financiers behave like narcissistic egotists at work, when they leave they can revert to a different mix. For example, they may reset into a caring parent (Homo Protectoris) playing imaginary pirate games (Homo Absurdum) with their kid in a garden with plants they care for like good friends (Homo Ecologicus). What’s important, though, is that those caring, playful, ecological parts of themselves struggle to express themselves in the market setting, and are pushed to the periphery in that context.

This has ideological implications, because Homo Economicus, as a central archetype in the system, also becomes a kind of Ideal that’s deployed by elites to justify and describe why they do the things they do. We’re not arseholes. We’re just doing what humans do, and should do.

Every person is multifaceted, but every person also has this ability to focus their awareness on a single facet of themselves and to politically identify with it. For example, one defining feature of conservative libertarian philosophy is a positive value placed on Homo Economicus (sometimes re-coded under new names like ‘the sovereign individual’), even though every self-described libertarian will also have socialistic and communistic traits within themselves.

But, even those who do not identify with the dominant values of capitalism - such as a self-described socialist - will nevertheless often be forced into bringing out their Economicus side. That’s because, regardless of your political ideology, you still have to survive through the capitalist market, and if you act against its prevailing tendencies you’ll quickly find yourself marginalised. We often live amidst a kind of evolutionary race-to-the-bottom, where if you don’t push the slider up on your dickish traits you get trodden on.

Approach 2: Capitalism as a harmonic filter and EQ

In Approach 1, I suggest that life under capitalism ups the volume of your Homo Economicus track, making it stand out more in your overall mix, but that metaphor assumes the other tracks remain untainted. They might be quieter than they should be, but they keep their integrity.

Our predicament gets deeper though, if we take a different metaphoric route, and start looking at the filtering and EQ controls found on a mixing desk - those knobs that can change the character of each track by shifting the balance between its frequencies. What if, under capitalism, there’s certain filters, or generic EQ settings, that start to get applied over each of our tracks? This is an imaginative exercise limited by the scope of our metaphor, but let’s explore it.

When someone says that something is starting to feel ‘commercialised’, what are they really saying? In a city like London, for example, there have been merchants selling coffee for hundreds of years, but why is it that a huge modern branch of the Starbucks chain in central London’s Oxford Street feels particularly ‘commercial’? Well, in an old-school market, there are many parallel vibes existing simultaneously. There’s trading going on, but there’s also gossip, friendship, lounging around, side deals, favours, communalism, and storytelling. In musical terms, there are a lot of harmonics, additional frequencies that resonate around the official main note. This is what makes a place feel soulful, edgy, informal and human.

A Starbucks does not feel like any of those things because, like any chain, they attempt to remove anything that isn’t dedicated to pure throughput of commercial trade at scale. This standardisation and formalisation is akin to the removal of harmonics. The store layout might look aesthetically pleasing, but it feels flat, as if all rogue frequencies have been pacified. In fact, if I was to say there’s a tinge of something inhuman about the chain, many people might agree.

In reality, those ‘rogue frequencies’ are often just other aspects of our being bleeding into spaces that might be the primary domain of one aspect of our being. The process of trying to purify a space of unsanctioned frequencies will always feel oppressive - whether it be a Starbucks enforcing an ideal of consumer optimization, or an overly zealous spiritual commune trying to enforce enlightenment - but the reality under capitalism is that the stripping out of non-commercial vibes is our most prevalent form of filtering.

In the case of a Starbucks, this stripping out of soulfulness is actually being applied to our Homo Economicus track, because - despite what economists say - our commercial trading side always contains harmonic traces of all our other sides. The inverse of this, though, is the process by which a capitalist system always attempts to boost the Homo Economicus harmonics in all non-commercial tracks. When a yogi starts to sense that there’s something empty about spiritual posturing on Instagram, or a punk complains that their countercultural neighborhood is getting ‘gentrified’, they’re both sensing that some previously non-commodified realm is being infused with added commercial vibes. The Homo Shamanicus track starts finding itself with a new shimmer of Homo Economicus harmonics.

Representing ‘commercial vibes’ in EQ format is an interesting metaphorical challenge, and I’m not sure I’ve yet fully worked out how to do it. Capitalism often promotes a seemingly contradictory mix of militaristic discipline in the workplace alongside undisciplined consumption in the marketplace, so as those values start to be overlaid over all our tracks, my intuition is that it boosts the aggressive mids of competition, and the tinny analytical treble of data-driven optimisation, all while cutting soulful bass. Feel free to share your own take on a capitalist EQ in the comments.

Approach 3: Homo Economicus as an Effects Unit

On a typical mixing console, you have the option to route each track through an external effects unit, which might be set up to - for example - add reverb to the track before bringing it into the final master.

This adds some new possibilities to our metaphor set. For example, rather than solely imagining Homo Economicus as an individual track among many, or as a harmonic added to other tracks, we might see it as an effects unit that all the other tracks must pass through before they can express themselves. This raises the question of what exact ‘effect’ it has. Is it a flanger unit, a compressor, or an overdrive, perhaps?

I think this metaphoric route works best when thinking about the struggles a person faces when trying to survive economically by doing something they believe in. For example, let’s take someone with a strong Homo Ecologicus track. Perhaps, in order to be able to make a living while pursuing this track under our system, they must route it through an effects unit - let’s name it the Marketizer 2000 - which is some kind of tone-shaping, frequency-sculpting limiter that will cut out any element of Homo Ecologicus which isn’t marketable, while boosting the elements that are.

Homo Ecologicus might enter the Marketizer 2000 as a feeling of connection to the natural world, but it might be forced to exit as a project plan to put a price on ecosystems in order to make them marketable. Homo Meditari might enter as a feeling that the world is crammed with excess, and exit as an online mindfulness app competing to sell itself on the Play Store as one product among tens of thousands of others. Homo Adventurous enters as a swashbuckling traveler, but exits as a lifestyle vlog on Youtube interspersed with adverts for AG1 supplements.

This version of the metaphor also provides us with a good way of critiquing some of the core ideological claims made by, for example, the tech industry. That industry always claims to be a bastion of creativity and innovation, and yet - under capitalism - the human spirit of innovation (which might be, for example, a mix of Homo Cogitans and Homo Expressio) is only allowed passage insofar as it molds itself to the requirements of the dominant track. Forms of creativity and innovation that don’t aim to extend commodification, accumulation, acceleration and expansion get muted, limited and marginalised. Big business doesn’t support creativity and innovation in general. It supports a very limited subset of that.

Mastering, and Remastering

The components of our metaphor can be combined. We might imagine life under capitalism as a situation in which we’re all tied together in a vast system in which almost evolutionary pressures start to emerge. They push up the volume slider on your Homo Economicus track while affecting the frequency of all your others. Making a living in that situation while remaining true to yourself is hampered by the fact that the dominant tendencies of the system stand like a bridge between you and your survival, forcing you to submit your dreams and authentic self to systemic restrictions. If you want to be an artist, learn to make it comply with the strictures of the market (or find a rich philanthropist who’ll insulate you from it).

All of this affects the master track of our being. That said, all of us will also attempt to alter this by adding in our own external effects units. For example, some might turn to religion, radical politics, underground grime music or meditation to provide some counterbalance to the dominant setup, while the dominant setup will try to re-route those very same impulses back through the capitalist mixing desk.

In some ways that sounds bleak, but this metaphor also provides us with some ways to think about creatively altering our system. How would you go about remixing your track levels? How would you boost the bass? How would you remaster the economy around you?

Hi Brett, thank you for your piece. Your analysis resonates with recent events in València, Spain, where I live. Our city experienced devastating floods that claimed over 200 lives, with many still missing in the metropolitan area. What emerged from this tragedy was remarkable: an overwhelming wave of solidarity. Thousands of volunteers from across the country came to help clean flood-damaged streets and homes. In the face of limited state resources, people and community organizations became the true front line against this disaster's devastating effects. Some citizens even walked kilometers from València's city center to assist neighboring towns.

This experience connects to your perspective on mastering and tracks because the tragedy notably amplified our capacity for altruism and solidarity, while diminishing the "homo economicus" mindset. To me, this demonstrates that in times of genuine hardship, humans naturally gravitate toward "mastering a track" that aligns with our deeper nature, rather than pursuing the self-interested economic logic that often drives our daily lives.

https://www.bbc.com/news/videos/czj7nnnwedpo

Hi Brett, this article really spoke to me. Music as a metaphor for capitalism really makes it easy to understand how we are being very "one tract" when we could be the whole 24 and experiment with re-mixing. I've love to chat more with you about what we are doing with micronarratives (think ethnographic), community projects and the finance community. I bet you can't guess which track we are finding the most challenging to remix!!