Paid subscribers can access the audio version here.

An interface is a surface that stands between you and a system. It hides the background circuitry, rendering it in a simplified form that enables you to interact with the system without understanding it. For example, the black screen is an interface between you and the underlying hardware of your smartphone.

Similarly, a web browser displayed on that screen is an interface between you and the Internet, a network of computers and data-centres connected together via telecommunications equipment.

A bank account page displayed on that browser is an interface between you and the transnational financial system.

We live with interfaces within interfaces, but some are harder to recognize that others. For example, a shelf in a supermarket is an interface between you and thousands of supply chains connected by planet-spanning logistics systems. The simple electricity plug point on your wall is an interface between you and the global energy complex. You don’t have to see or understand the messy geopolitics of coal, oil and gas to make your toaster fire up. You just need to plug in to the interface.

We didn’t always have interfaces like this. For much of human history, life was far more un-intermediated. 50,000 years ago we were locked into tangible and visceral direct engagement with environments, objects and communities. You could smell the antelope in the hide that covered you, and see the skeleton of the creature that provided it. Even 500 years ago life remained very direct. Walking into a city, you’d get an intense feeling of being in a very specific place in a very specific time. You might inhale smoke, released from the direct burning of charcoal to cook meals, while you navigated through informal markets displaying unpackaged goods from nearby localities.

As you moved through cities, you’d see the local owners of stores, inns and stalls, and notice idiosyncratic signage that changed by locality. There were no chain stores owned by faceless institutional shareholders with common branding and common interfaces. There was no overlay of an omnipresent Google Maps that positioned you as a constant blue dot in the centre of a two-dimensional rectangle. Your attention wasn’t being drawn to a different locality through the ping of a WhatsApp notification. If you were in a place, you were intensely there, and nowhere else.

The trend over time, however, has been formalization and standardization. Informal peer-to-peer systems slowly get dissolved and replaced by large-scale formal bureaucratized systems that stretch across time and space. This gradually pries us away from direct experience. You don’t see your neighbour cutting the throat of a goat any more. You see them with a bag of groceries containing plastic-wrapped, industrially-farmed beef cutlets. This increased indirectness dilutes the intensity of day-to-day life.

This disassociation from directness has accelerated under modern capitalism. The romantic image of the ‘free market’ is one of face-to-face street bazaars, but the core feature of actual modern capitalism is that firms get bigger and bigger, a process mirrored in us gradually being pulled ever further from the underlying people, ecosystems and resources that underpin any economy. Corporations wage war on direct informal systems (see The War on Informality), which are imagined to be slow and inefficient. They seek to replace them with central systems that we indirectly interact with via interfaces.

This formalization is one key feature of ‘economic development’. If you visit a so-called developing country, you’ll immediately notice diverse veins of informal markets that draw from regional supply chains. A developed country, by contrast, is dominated by formal supermarkets that act a standardized conduits for transnational corporate supply chains. This formalization extends across industries. For example, in 15th century Europe there were cross-country branches of powerful banking families, but financial markets included spidery networks of relationship-based trade credit and informal moneylending. By the 19th century those webs of credit were getting formalized into corporate banks with standard branches replicated across cities and countries. 20th century corporate capitalism is the result.

Get a free taster of my 10-part Intro to Economic Life course here:

The pronouns of corporate personhood (and its interfaces)

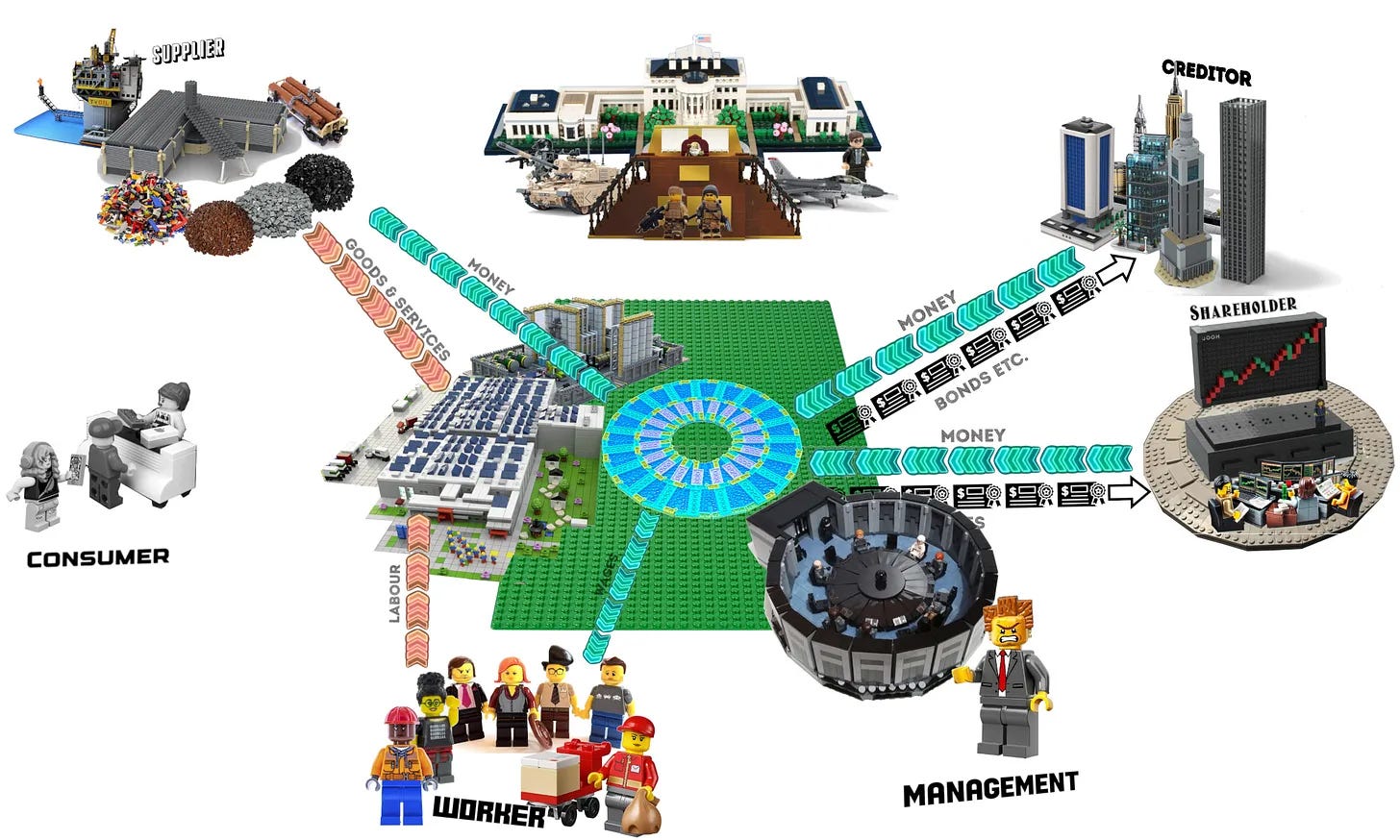

In my Lego Model of Corporate Capitalism, I created a simplified representation of the different groups that come together to bring a corporation to life:

This entity is a conglomeration of thousands of disparate individuals who are trying to work together, normally under a central hierarchical command structure. From a legal perspective, however, this conglomeration is a single ‘thing’. In the centre of the image above there’s a blue circle. This is a hollow legal shell created through an act of incorporation. It’s given a name - such as ‘BP’ - and this named entity is granted legal personhood, the legal right to act as if ‘it’ were a natural person (i.e. a biological human being). ‘It’ can enter into contracts, hire people, sell things, sue people, issue statements, and so on. It’s a creature given life through law (and capitalization), but it can also die its own death without bringing its humans down with it: this is the concept of limited liability.

Linguistically, when we’re referring to this creature of law - the legal person - we use the company’s name. For example, ‘BP hired 5000 new workers’, or ‘BP is investing into renewables’, or ‘BP issued a statement about climate change’. In reality, BP is a legal construct that cannot do anything unless actual people do the things for it. This is why there’s a taboo against using personal pronouns when speaking about the legal person. We’d never say, ‘BP is investing into renewables because she is concerned about climate change’. We’d either say ‘it is’, or we’d refer to the underlying people by saying ‘they are’. A BP press release is not going to say ‘Hi, this is BP here. Climate change concerns me, and I pledge to do something about it’. No, the PR team will write, ‘climate change concerns us here at BP, and we pledge…’

Nevertheless, because a corporation is an artificial legal person operated by real people, we always have two separate ways we can experience it. We can experience the real people, for example, by chatting to the clerk at Walmart. Alternatively, we can experience the legal person, by noticing that the clerk has a branded uniform over her real body, and that this specific building is arranged in a particular way that represents a universal Walmart-ness that transcends this specific place. We might notice the decals on the delivery van that tell us this specific Toyota isn’t just any Toyota, but rather a Walmart van. The branding overpowers the Toyota-ness - owned by another undead legal construct called Toyota - that previously lingered around that vehicle.

All of these things - brands, colours, catch-phrases, signature arrangements - are merged with the service staff to form the outward-facing physical interface for the corporation. For much of the 20th century, these physical interfaces were the primary way the public interacted with these legal persons, and the taboo of not referring to the latter with personal pronouns was passed on. The Walmart cashier would never say ‘How may I, Walmart, help you’. Rather, she’d refer to the staff by saying ‘how may we help you’, or to herself with, ‘Hi, I’m Sandy, how may I help you’. The Barclays Bank branch might have a poster urging you to ‘speak to one of our staff about our new mortgages’, but would never say, ‘speak to me about my new mortgages’.

The thickening, and the stickening

By the mid-20th century, people in urban areas were interacting with physical corporate interfaces in almost every industry. These not only distanced them from the underlying reality of how they survived (aka. global food, commodity and energy supply chains), but could be used to steer their understanding of that reality. Nevertheless, the interfaces were still only a mottled patchwork. Informality, non-standardized practices and smaller-scale local systems still thrived in the urban underground, immigrant neighbourhoods, smaller towns, and in rural areas.

Then came the explosion of the Internet. One of the Internet’s original features was to enable digital ‘store-fronts’ - a website - to be built in one computer in one place, and then ported via telecommunications infrastructure and common protocols to another computer in another place. In this way, a carpenter in Manchester could port their store-front into your living room in London. By the 1990s, this had created a utopian peer-to-peer vision for the Internet. It was imagined that small-scale operators could set up their storefronts on each other’s computers, weaving together a distributed digital equivalent of an informal market.

In reality, though, we live under capitalism, and the romantic vision of the bazaar-like horizontal market is just an ideological cloak for a much darker reality. A large-scale capitalist system always defaults to expansion and acceleration, and if you attempt to go against this trajectory you eventually get shafted. Predictably then, the original horizontal Internet got shafted by the expansionary, accelerationist version. Billions of people were slowly nudged by the systemic default towards massive datacentres owned by big corporates. Rather than dealing with each other, we’d all go via the corporations.

This not only replicates the same formalization and standardization processes that occurred in the physical world, but actually supercharges them. Note, for example, that 6000 bank branches have been shut down in the last 9 years in the UK, creating much angst. In the 1800s, bank branches were the face of corporate centralization, but nowadays they supposedly represent localization, because the new normal is for the corporate to get rid of its branch network and replace it with standardized apps that directly tether tens of millions of individuals into their centrally-controlled datacentres. The real breakthrough for the corporates was the smartphone, a device that not only allows a store-front to be ported into someone’s world from a distance, but which follows them everywhere they go. The corporate interfaces now literally stick to us now like an inescapable coating.

Old corporations would normally start by building their supply chains, and would then output their products via a physical interface, such as a store staffed by uniformed service staff. Those legacy corporations are now trying to replace their physical interfaces with self-service apps, but new corporations without legacy customers frequently now start as digital interfaces, and then slowly reverse-engineer all the supply chains required in the background. Many tech startups are just interface-builders. For example, Pets.com tried a slide a digital interface between pet food supply chains and us. Spotify slides an interface between us and music catalogs. Uber slides one between us and physical taxis, and between taxi drivers and their customers.

The biggest development in our world, though, isn’t just this new breed of corporates obscuring physical supply chains with digital interfaces. Rather, it’s those companies that provide interfaces into the interfaces, the platform corporations that act as infrastructure for all the others. This is Big Tech, and it’s their interfaces that have become the most pervasive, iconic, and inescapable. They stick to us everywhere we move, and colour our entire reality. You cannot turn on a computer without experiencing the Microsoft or Apple interface, or a phone without experiencing the Apple or Google interface. You increasingly cannot communicate without seeing the green of WhatsApp, or travel without picturing your destination as a red pin on Google Maps. You cannot experience diverse images and videos without them being framed by the unchanging interface of YouTube, Netflix, Instagram, Google Images or TikTok. Goods made by diverse people in diverse places get pushed into standardized boxes under a search bar on Amazon.com or JD.com.

For the first time in history, then, the entire planet is almost fully covered in a thick layer of intermediary interfaces-of-interfaces. These do vary across regions - China has a different set - but they’re beginning to blend into a collective collage as one ports into another - a Maps location is shared via WhatsApp, or an Instagram image links to Amazon.com. This collage is becoming a meta-interface that covers the world like a membrane between us and everything. The membrane functions like contact lenses, rendering every city layout or image in the same format. It affects other senses too. Every song is subject to same algorithmic curation, while ideas for what food you will taste are constructed in your mind via Instagram and YouTube interfaces.

It goes without saying that this profoundly affects the very way we both perceive and experience the world, but we’re also fed a story that says this membrane belongs to us. We’ve all been enlisted into thickening it by contributing images, videos and text to what superficially appear as common frames. But we do not control these frames. They’re corporate assets, owned by hollow legal entities accountable only to execs, creditors and shareholders. Critics of capitalism have long lamented how the profit-motive distorts our perspective on the world, but they originally meant this somewhat figuratively. Nowadays, however, the profit-motive will literally shift your perceptions via the curation of the meta-interface. Your small business store-front might physically exist, but if it’s not prioritized by Google Maps people might walk right past it as they follow the algorithmically-mapped path on their screen towards a different pin.

Would you like to syndicate this essay? Contact me here

The three new faces of corporate personhood

Corporations are operated by humans, but the corporation itself is an undead entity with a default setting to maximize profit. This poses a problem. There’s something fundamentally gross about the way the legal person - the hollow shell - always appeals to warm-blooded things like friendship, solidarity, adventure, family and love in its sterile pursuit. No matter how hard the legal person tries to pretend to be a natural person, ‘its’ messages always reek of inauthenticity. The predictable move for an entity that that, then, is to try change its interfaces into a human face, to cloak the legal person in the literal image of a natural person. This new attempt to ‘personify’ the corporate mask has three faces.

Face 1: Your face

Old corporate interfaces presented a relatively common front to all who approached. The Barclays or Walmart staff might have adapted their behaviour depending on who they were speaking to, but there was some attempt at common treatment for all customers. The new digital interfaces, by contrast, don’t present a common view. They shapeshift. They build a wire model of you from webs of collective and personal data, and then try to mirror that via the interface. The YouTube you see has the same colours and layout as the one I see, and yet we’re not present in each other’s space like two customers browsing through the same record collection at a music store. The Internet is seldom used to ‘connect us together’ any more. No, we’re each in a private bubble.

In a sense, the new digital interfaces are like a reflective store-front made of one-way glass. Whoever approaches will see an image of themselves, reflected in what products turn up, and what messages they receive. The corporate can see them, but the person is encouraged to imagine themselves as walking through an uninhabited room with shelves that belong to them: my shelf, my basket, my account, my list, my favourites, my Amazon, my Google etc. In the 1980s there was no ‘my Walmart’, but now your data is reflected back to you as your own store with that possessive pronoun. In doing that, they get to present themselves as you.

In recent years this mirroring sometimes turns in ‘your year in review’ summaries, like Spotify Wrapped. Strangely, this is the only time you can detect the one-way glass. In so overtly saying here’s a packaged image of you, you sense the presence of a watcher. “We’ve been watching your every move around our music store… sorry, your music store”.

Face 2: I, AI-bot

Traditionally, if Bank of America contacted me, they might send a letter saying 'We are writing to inform you...' Their chatbot Erica, by contrast, uses the personal pronoun ‘I’. I noticed that your Joe’s Gym recurring charge was higher than usual.

Who is this ‘I’? The bot is just lines of code hosted in computers within a data centre. The code gets triggered when you connect to that via your phone. It outputs text that is ported into your world through the digital interface. It functions as an automated answering machine, like a dynamic FAQ that rearranges itself after the Bank of America IT system interprets your words.

This combination of code and computers will be found on Bank of America’s balance sheet under its fixed assets. ‘Erica’ is legally in the same category as the bank’s supply of staples or fleet of vehicles, but they don’t give human names to their water coolers or keyboards. They only grant that to assets that form part of the new outward-facing interface. They encourage us to get on first-name terms with this combination of code and hardware, and by now all of us have experienced the proliferation of these named interfaces like Alexa, Bard, Claude, or Jasper.

These chatbot interfaces are now being integrated with pipelines that send your requests into AI systems that will offer forms of ‘companionship’. Microsoft’s Co-Pilot overtly invokes the idea of a helper sitting beside you, while the Zoom interface now includes a new ‘companion’.

These AI prompts are now imparting a certain animate feeling to previously inert-looking interfaces. We’re supposed to imagine these corporate assets experiencing the same natural personhood as we do, as we ask ‘them’ for help, but these processes are just data centre operations. The silicon chips feel nothing of the emotions you feel, don’t share your goals, and cannot experience the meaningful distinctions you might make between, say, processing information for nuclear warfare or for humanitarian aid.

The animist in me respects the idea that the components of a computer might experience their own form of personhood, but if I do that I must also respect the personhood of a piece of granite in a garden tile, or a dust particle floating in the air. These forms of personhood might exist, but they’re not personhoods we have access to. So, it’s arbitrary when a corporation encourages us to say ‘thank you’ to its bot, but not to a plastic wrapper in a bin. That wrapper experiences the same personhood that Erica does, but we’re supposed to speak to the latter, and ChatGPT, and all other AI interfaces, as if they were discrete beings, rather than networks of disparate components.

This is narcissistic, because it’s only objects designed to mimic human responses that get given this pseudo natural-personhood status. So, if the first phase of ‘personified’ corporate personhood looks like our own face reflected back to us, the second phase involves channelling that reflection through a machine system designed to mirror the image of another human. Put differently, AI chatbots give the one-way mirror a human name that’s different to your own. “I’m having a conversation with Erica”, you think to yourself as you transmit information to the (largely male) engineers of Bank of America. “She knows me so well”.

Face 3: The tech baron

How many Big Pharma CEOs can you picture in your mind? Do you know the names of the Big Oil execs? Who leads BHP Billiton, or Wells Fargo?

Unless you’re in elite business circles, it’s unlikely that these names and faces will easily come to mind. A reasonable chunk of society might know some of the finance bosses like Jamie Dimon of J.P. Morgan, but almost everyone knows the tech billionaires. It’s hard to find someone who hasn’t heard of, and seen images of, Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, Peter Thiel, Elon Musk, and Bill Gates.

A tech startup is like a nascent speck in the universe until the systemic forces of capitalism decide to channel through it and it explode it outwards into a mega-star in a matter of months. As the company turns into a ‘unicorn’, their hapless, and often clueless, founders are taken along for the ride. The sheer speed at which they become billionaires creates an aura of mystique, and they ascend to a panoply of business demi-gods that hover above us. Witness, for example, the recent meteoric rise of Sam Altman.

The tech billionaires are our most visible class of capitalists, and they have certain skills and talents, but given that they’re fallible humans like anyone else, we have to also deal with their often banal visions and arbitrary decisions - like Zuckerberg’s cringe vision of the Metaverse, Altman’s shallow vision of Worldcoin, and Elon’s random perspectives on immigration (or gym routines, or whatever).

We return to the interaction between the legal person and the real people. With most old companies this distinction was fairly clear, but tech founders often retain controlling stakes of their startups, and when those startups explode the founder ends up with outsized control. A banking CEO like Jamie Dimon only holds about 0.02% of J.P. Morgan’s shares, while Zuckerberg owns 13% of Meta, Thiel 10% of Palantir, Bezos 9% of Amazon, and Musk 80% of X.com.

The CEO of BP - Murray Auchincloss - is hired by BP shareholders, and they will fire him if he fails to serve them. Tech billionaires, by contrast, are like barons that control a fief. They’ll allow outside investors to join them, but won’t cede control. In a traditional shareholder-dominated corporation, the comparative ‘facelessness’ of the shareholders means the interfaces stand in as the dominant face of the company. Big Tech interfaces, by contrast, stand alongside literal images of their barons. In fact, it’s those interfaces that serve us the pervasive images of them, as Elon is constantly forced into your X feed. Their image is slowly built in the back of your mind as you stare into the one-way named glass.

Facing AI-nxiety

The GoogleMetaAmazonMicrosoftAppleNetflixSpotifyLinkedInEtc meta-interface is stuck to us now. It tints and curates our world, but provides no comfort. In fact, it gives us anxiety. Historically people felt this emotion at the prospect of looming economic downturns or geopolitical instability, but now minor shifts in the Google algorithm can make tens of thousands of businesses literally disappear from view. Small UX changes on WhatsApp can make or break your romantic relationship.

The collective meta-interface is subject to unaccountable changes that affect the very colour and texture of the everyday, but this sense that we’re no longer in control of own view on the world gets even more edgy with AI. Our fear at this new technology goes beyond our jobs being at risk. AI is a way to make corporate interfaces ever more invasive and dominating. That’s why every tech company is pushing us to use it, like digital meth dealers. Here, we’ve integrated your new AI assistant into every interface box that your career depends on. There’s no opt-out.

Look at all the tech barons, clawing for processing power to run the new face of corporate personhood. Their desperate race has pushed Nvidia’s stock up hundreds of percentage points within a few short years, launching the GPU-maker’s founders into demi-god status. The progress narrative that accompanies this says that this arms-race empowers us, furnishing us all with endless convenience (see Tech Doesn’t Make Our Lives Easier. It Makes them Faster), but this sits uneasily alongside the overwhelming feeling of paternalistic control that surrounds these platforms.

To ease our fears, we get told that tech overlords are swept to power by us. It’s consumer desire that explodes their platforms into all-encompassing environments. The reality is far simpler, and darker. Just like Microsoft Windows is a default that loads without anyone choosing it, corporate capitalism is an operating system that loads up every morning. You don’t have to choose to expand, automate and accelerate. Those are default processes that play out regardless of your desire. The role of the tech CEO is to extend the systemic default, cheered on from behind by a sycophantic class of institutional shareholders.

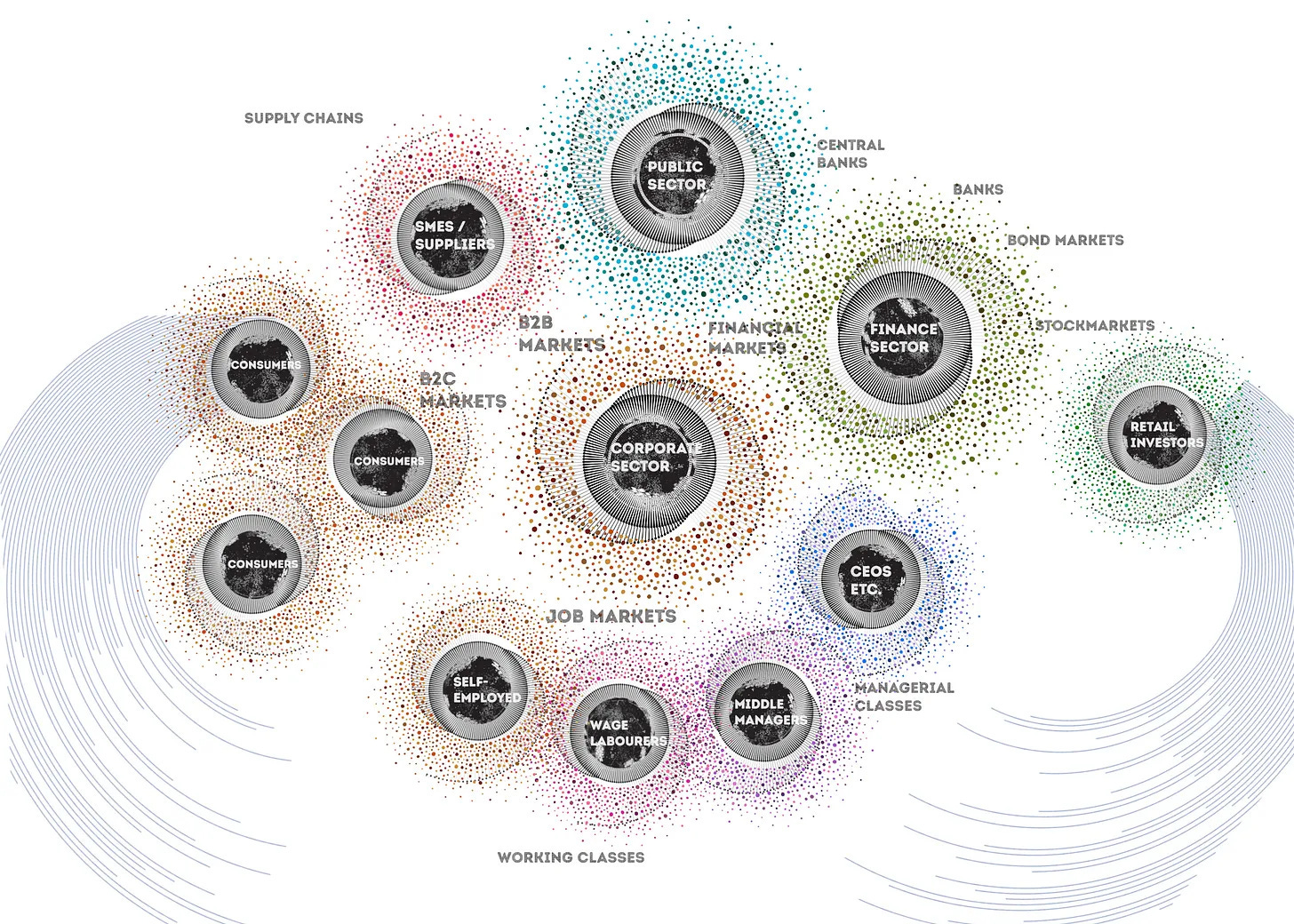

But, while there’s a real person called Sam Altman, Jeff Bezos, and Peter Thiel, experiencing real human emotions, hopes and fears, their grinning faces are also inhabited by artificial legal persons. After all, corporate capitalism is a circular system, with all the nodes in it eventually touching all the other nodes. We’ve been discussing the interface between the corporate and customers, but there are other interfaces too, between corporates and workers, supply chains, the finance sector, and state. These are all interlocking sub-systems interfacing with each other…

Crucially, every one of these interfaces, eventually, go both ways. Zuckerberg’s image might be projected outwards, but from his human vantage point, we are the faceless systemic tsunami that gives him power. In fact, without that tsunami, his face is not known at all. As his image is constructed in the public imagination, he becomes an avatar, an artificial picture of a natural person, pasted over the face of capitalism.

Well written, Brett. Your article has helped contextualize some recent personal reflections on my career as a graphic designer and future projections. When I was back in arts high school dreaming of a creative career, it definitely wasn’t laying out digital rectangles inside a physical hand-held rectangle, to make a rich corporation appear trustworthy. After years of experience I am well aware that designers are instrumental at shaping the look of corporate interfaces. Design is a powerful tool that helps build trust with faceless corporations (or distrust…lol @the above Oatly debate.) I have always tried to use my powers for good, but it feels like the opportunities to do that while making a living, are narrowing - this is probably the case in other domains as well not just design.

I’m not completely pessimistic about the future, but it is indeed a strange reality we are living in—with friendly faced interfaces masking a much darker reality.

The only relief is a daily connection with non-interfaces.