Intro to Economic Life 8: Economic Numbness

Why our system is an elephant we can't see, or feel

The first third of this piece is open to everyone. You can unlock the full piece, and the whole Intro to Economic Life series, by upgrading to a paid subscription

The Buddhist fable of the Blind Men and the Elephant tells the story of blindfolded sages who touch different parts of an elephant - tail, thigh, ear, leg, tusk, and trunk. They imagine them to be a rope, a wall, a fan, a tree, a spear and a snake. The moral is simple: if you can’t see - or feel - the bigger picture, you’re going to imagine it as several smaller pictures.

In Part 7 we saw how modern corporate capitalism is like this. It’s too big to see, so rather than appearing to us as a whole system, it appears to us as a series of fragmented interfaces. We touch different parts of our system via these interfaces, and as we do so, we’re encouraged to create disconnected personas for each touchpoint.

Look at the business section of any newspaper and you’ll find stories with headlines like ‘US consumer sentiment drops’, ‘Germany faces shortage of skilled workers’, or ‘shareholders optimistic about tech stocks’. They’re presented as separate stories about fundamentally different sorts of people, and yet all of us could be all of these at once. A German immigrant to the US is a worker as they walk to the office in the morning, but if they stop outside to buy a coffee first, they’ll be a ‘US consumer’. If they ignore the Starbucks and drink the office coffee instead, they’re a saver, someone who opts to not spend. Perhaps they’ll put that money towards buying extra shares in a tech company. This single person could be a source of all the newspaper headlines above.

We seldom think like this though. Rather, we compartmentalise ourselves as we interact with separate interfaces, each of which conceals more than it reveals. For example, your consumer persona browses a supermarket shelf, which is an interface that hides countless underlying supply chains. Later, your saver persona thinks about their pension, which might be invested into numerous mutual funds that collectively invest into hundreds of corporations that own tens of thousands of underlying subsidiaries all over the world (see A Lego Model of Corporate Central Planning).

As your consumer persona picks up a carton of soya milk, they’re totally unaware that your saver persona might be indirectly invested in companies that supply the firm they’re about to buy a product from. Your saver persona doesn’t know that either, though, because all they see is an account statement from an investment manager.

Many steps removed, your consumer persona might actually be one of the sources of income for your saver persona - a tiny fragment of the money handed over for the products you buy might end up making its way into your pension. Nevertheless, these different parts of yourself not only appear as strangers to each other, but as strangers to the underlying reality of what they’re doing. You can’t see all the connections.

So, the underlying reality is that each of us is a whole person in a whole system, but we don’t perceive that. Rather, we perceive fragments of ourselves in fragments of the system. It’s little wonder that we struggle to understand the ‘elephant’ right in front of us.

Seeing the elephant

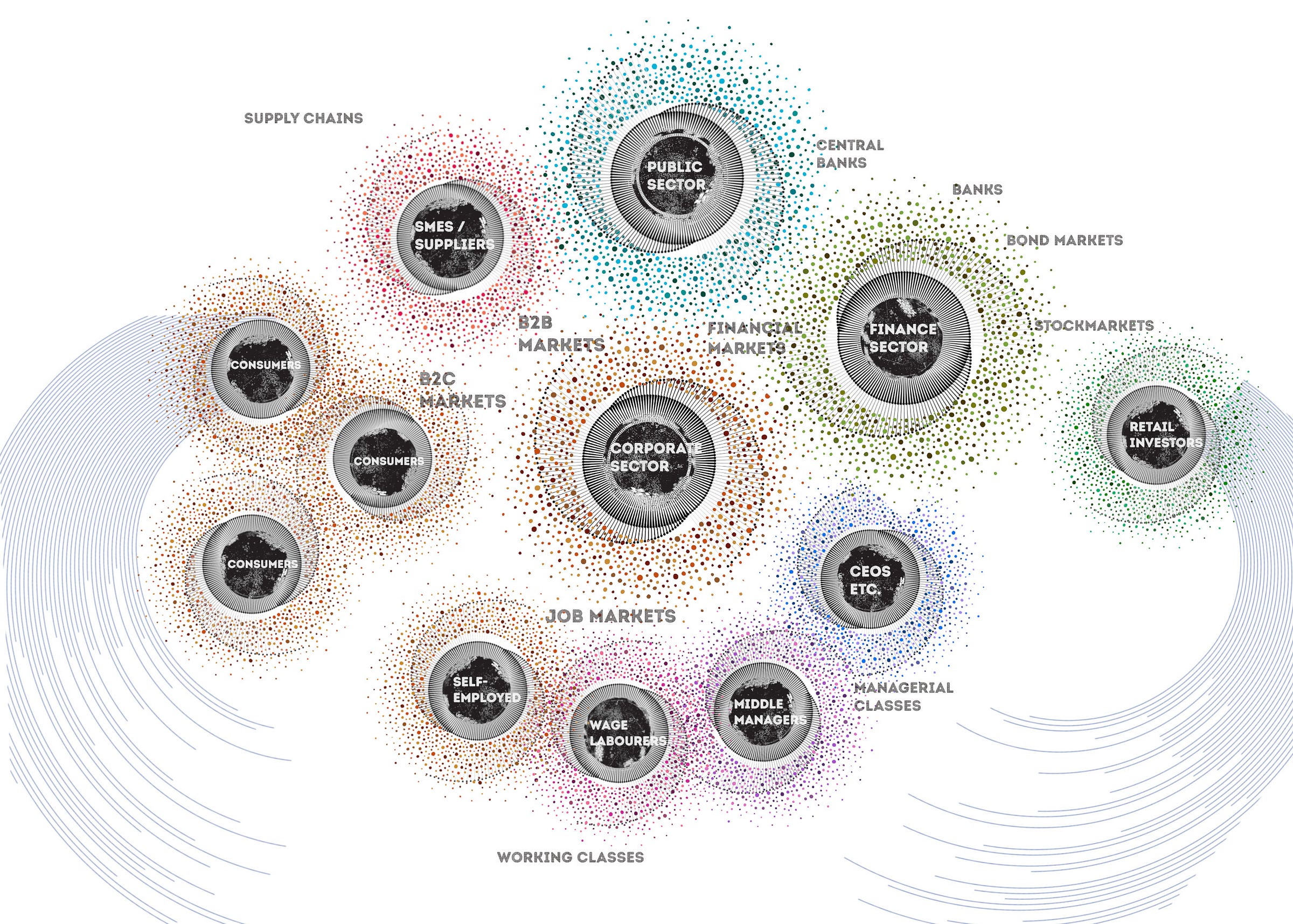

In Part 7 I encouraged us to start looking at that whole elephant by using images from my Lego Model of Corporate Capitalism series, like this one:

This is a highly simplified representation of the interlocking parts of a single corporation. The core of capitalism is made up of a tangled mass of these entities, but if we took all these corporations and companies, and clustered their separate components into common categories, we’d see distinct sectors, markets and classes of people. Let’s begin by mapping these onto the picture of a single corporation…

Let’s now remove that background image of the single corporation to reveal the big categories.

In Part 5 we looked at how the market vortex forms, and - at one level - that vortex is a single system, much like an elephant is a single creature. You can, however, also see an elephant as a series of sub-systems in complex symbiosis. Similarly, the image above is showing the single market vortex as a series of sub-vortices in complex symbiosis, held together through different interlocking markets.

Let’s look at those sub-vortices. As a class, creditors and shareholders are big players in the financial sector, and that zone between them and the corporate sector is called the financial markets. The zone between different working classes and the corporate sector is called the job market. Suppliers seek to sell into the B2B (business-to-business) markets, while consumers operate in the consumer markets, which also get called B2C (business-to-consumer) markets.

These neat categories are an abstraction. An actual economic system is a tangled mass, and there isn’t a single location for each of these sectors and markets - they’re all over the place, superimposed and mixed with each other - but we can abstractly pull them apart and imagine each of them as having their own internal logic to some extent. They form hidden centres of gravity under the surface, and at different times can exert different pulls on the overall system, and have different levels of power.

There isn’t really a beginning or an end to this system, because all the parts feed into each other. For example, the corporate sector sells shares and bonds into the financial markets in exchange for money, which they’ll use to buy assets from B2B supplier markets, and to hire workers in the job markets. Those workers will input their labour into the corporate sector to operate the assets, which will output goods into B2B or B2C markets (depending on what industry they’re in), and thereby extract money back into the financial sector. Small slivers of that money might then end up with retail investors (like our aforementioned mutual fund saver) who might use that to buy more things.

I place the corporate sector in the middle of the image above, because the corporate sub-vortex is a focal point in our system. As mentioned in Part 7, almost every industry in the world is dominated by an oligopoly of players - often no more than 10-20 big players - who have entrenched themselves into the centre of our system. These entrenched central players pulls upon us, either directly through products and jobs, or indirectly through supply chains, pension funds and so on. As mentioned in Part 6 and 7, even if you work for a small company, it will often be dependent at some level on corporate products or corporate customers. This means many of us will consciously or unconsciously orientate ourselves towards mega-firms. This is why we use that term ‘corporate capitalism’ - it refers to a style of capitalism in which big players cluster in the centre.

That said, there isn’t really a single centre to our system, because the parts fold into each other: in the image above, for example, I have currents moving around the outside from workers into retail investment and consumption. Furthermore, there are other strong sub-vortices such as the public sector, which sometimes aligns with corporates, and at other times pushes against them.

The other big nuance is that our economic system is transnational - it’s a global system - but it can also be seen as a series of national sub-systems tied together. This adds extra complexity to the picture: for example, China is a major player in the global capitalist system, and yet - at a national level - Chinese corporates often orientate themselves around the Chinese state. In the UK, by contrast, the financial sector is the core national industry - which means the local economy and politics orientates around it - but that national industry plays a core part in the transnational system: many companies from across the world use the UK financial sector.

Intervening in the sub-vortices

When we zoom back out to the big picture of the overall market system, we see systemic tendencies that pull in some directions over others. For example, companies have got bigger over time, rather than smaller, and inequality has got worse, with small numbers of people having vastly more than others. As we saw in Part 6, the system certainly tries to constantly expand and accelerate, but it also goes through periodic contractions (‘recessions’).

Needless to say, over time people have attempted to modify these systemic tendencies through policies, regulations and institutions. For example, governments can use anti-trust laws to try break up huge corporations into smaller parts, but those parts will often seek to reassemble themselves in a new form somewhere else in the system. Individual corporations frequently break sections off themselves and then recombine in new clusters through mergers and acquisitions.

Governments can also intervene via fiscal policy - decisions about where to spend and tax. In this course we’re not doing a deep dive into the international monetary system (that would require a separate course), but it’s crucial to remember that the monetary system holds together the overall market vortex, so monetary institutions like central banks will try to affect the different sub-vortices through monetary policy.

Intervening in the intersections

It’s also useful to explore each intersection between the parts, both locally and internationally. There are special bodies that seek to manage each intersection. For example:

Boards stand between shareholders and managers, to make sure managers are acting on behalf of shareholders

Unions might stand between the workers and managers, to fight for better pay and working conditions, and to lobby for better workplace regulations

Consumer protection groups stand between customers and the corporate sector, to fight predatory practices and to promote product standards

Government regulators will step into all the intersections to try to steer them: Labour regulations govern relations between companies and workers, consumer regulations govern relations between corporates and consumers, and financial regulations might govern relations between large financial institutions and smaller retail investors, or between the finance sector and firms. There’s also corporate governance regulations to govern relations between shareholders and managers

Transnational intersections: we also have a whole raft of international accords, agreements and institutions to try deal with transnational intersections. For example, the World Trade Organization is a big player in the relations between corporates and their foreign suppliers, or between local customers and foreign sellers

There isn’t scope in this course to cover all of these, or to dive deeply into all these specialist topics, but all of them are set within the overall transnational system, attempting to exert some form of control over the fluid and insecure market networks.

Four Views on a Compartmentalised World

Most of us struggle to see this transnational picture of complex and morphing interdependency. Rather than perceiving ourselves as passing through different sub-vortices in a large interconnected system, we’re trained to just see separate pictures. And, as these different parts get played off against each other, our internal personas get played off against each other too, often with highly political consequences.

For example, corporate sector executives might showcase about how they serve us as consumers with cheap goods, but those cheap goods might be cheap because the corporations use market power and economies of scale to drive down worker wages or dominate over foreign SME suppliers.

At other times, we might feel frightened as consumers by ‘cost of living’ increases - when goods get more expensive. That fear will be acute if our wages are not going up as fast as prices, but we live in a closed system and the prices are being paid to the companies. So, if a higher price is being paid by consumers to the corporate sector while wages aren’t increasing, who is claiming the excess? Well, look at our diagrams. The money has to go somewhere. It could possibly be going to a set of external suppliers (for example, the oil sector during an oil ‘shock’) but it could also just be going to the shareholders and managers.

If workers realise this, however, and go on strike for higher wages, the shareholders of businesses can get consumers to turn against them by claiming that the workers are disrupting the consumers, or that the demands for higher wages are themselves the source of inflation. Unless you can see the interlocking parts of the sub-vortices, it’s going to be tricky to untangle these claims, especially in a transnational system where there are many sub-systems with ambiguous connections. This is why you can have TV commentators having wildly different interpretations of where various macroeconomic phenomena are emerging from (this ambiguity also allows different interest groups to pick and choose what narrative they’ll use to describe those phenomena).

Needless to say, you might find yourself caught between these tendencies: for example, you might find yourself in a part of the system where you’re paid too little as a worker while being worried about the cost of living as a consumer, so you might seek to compensate by making money in the stock markets as an investor. You buy shares in companies that are run by managers that believe they must boost profits by paying workers less while charging consumers more. See what just happened there? One class that you’re now part of - the financial investor class - seeks to benefit from the suppression of two other classes you’re part of - the worker and consumer class. You’re potentially at war with yourself.

To understand this more clearly, we need to travel to different vantage points in the system to look at the world through the eyes of the persona or group who resides there. How does each perceive their own situation and problems, and how does this relate to the others? Let’s go through four of these viewpoints, starting with the view from the financial sector.