Paying subscribers can access the audio edition here

Just a quick note about this piece: Sometimes I write these more experimental (and slightly more technical) pieces, and they’re semi-unfinished because they’re leading on to other pieces that will fill in other parts of the picture.

So, this essay is really dedicated to explaining the commodity imagination of money and how it comes about. It’s a style of thinking that I don’t subscribe to, but it’s useful to understand how it works, because it’s the dominant way people think about money in society. Understanding it will also help you to understand, for example, the rhetoric used by the Trump administration when speaking about Bitcoin.

You’ll notice, though, that as you go through this essay there are certain things left unexplained. I’m well aware of that. In particular, you might notice that I hint at, but don’t explain, an alternative way of thinking. That will come in later pieces. With that said, let’s start.

Starting points matter.

In this piece I’ll show you how your starting assumptions about an economy can in turn lead to certain beliefs about money. In particular, I’ll show you how a belief in individualism generates a belief that money is - or should be - a commodity.

I’ll conclude by showing you how this maps onto the Bitcoin industry, and in a follow-up article we’ll use this to understand the ‘crypto strategic reserve’ announced by the Trump administration. This will take some peeling though, because the underlying ideology goes far deeper than crypto itself. Let’s start with the myth of independence.

The myth of independence

In the libertarian worldview ‘every man is an island’, and the economy is seen as a big collection of individuals who voluntarily choose to trade stuff.

This view is in fact very common, even among people who don’t officially subscribe to libertarianism. Actually, many people will find themselves subconsciously seeing the economy a bit like this, because it’s a worldview that organically emerges in a large-scale market system. As you walk through city streets past strangers who ignore you, or drift through shops looking at ten different brands of shampoo, there’s a general feeling of detachment.

In Detachment Theory I explained that this is a perception, rather than an economic or social reality. We’re not truly ‘independent’. Rather, we’re deeply interdependent. Even the most basic things you survive upon are created by millions of others, and nobody is truly detached and ‘free’ from those others.

In fact, we’re compelled to connect into those others, because we have no true ability to exit into some alternative reality in which we survive alone like a wilderness hermit. The interdependent economy is our life support, and - at most - we have some limited wiggle-room to shift where we plug into this insecure, unequal (and often coercive) mesh.

That wiggle-room might express itself to you as ten different brands of shampoo, each representing a slightly different supply chain path that you can take to clean your hair. Each path is made up of interlocking sequences of millions of people that stretch back through time and space, with each link in that chain jostling to wiggle into a slightly better position within the mesh. This wiggling is what we call ‘free markets’, but this limited ‘freedom’ occurs within constraints.

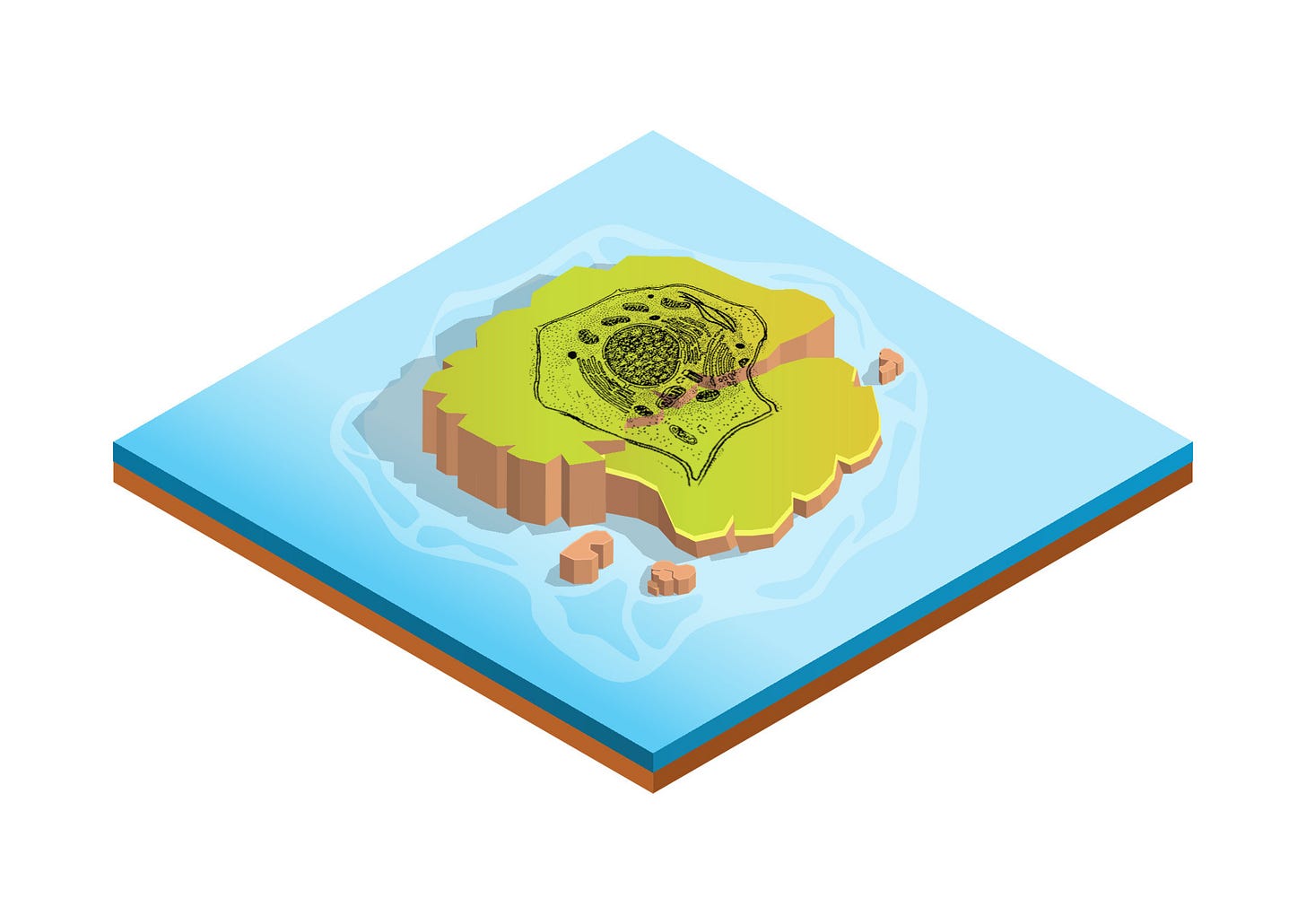

The best way to picture this is to think of your own body, which is also an interdependent system. Imagine your liver cells breaking away to ‘seek a better life’ on the outskirts of the heart. They might succeed, but others are going to have to take their place in the liver, otherwise your overall body is going to have a serious problem.

Similarly, you might have a romantic image in your head of every person being a heroic entrepreneur who can escape to a better life, but if that was to be a reality, many things around you would dissolve into nothingness (such as your phone, which requires a whole bunch of people to be doing jobs like mining cobalt for some global commodity corporation).

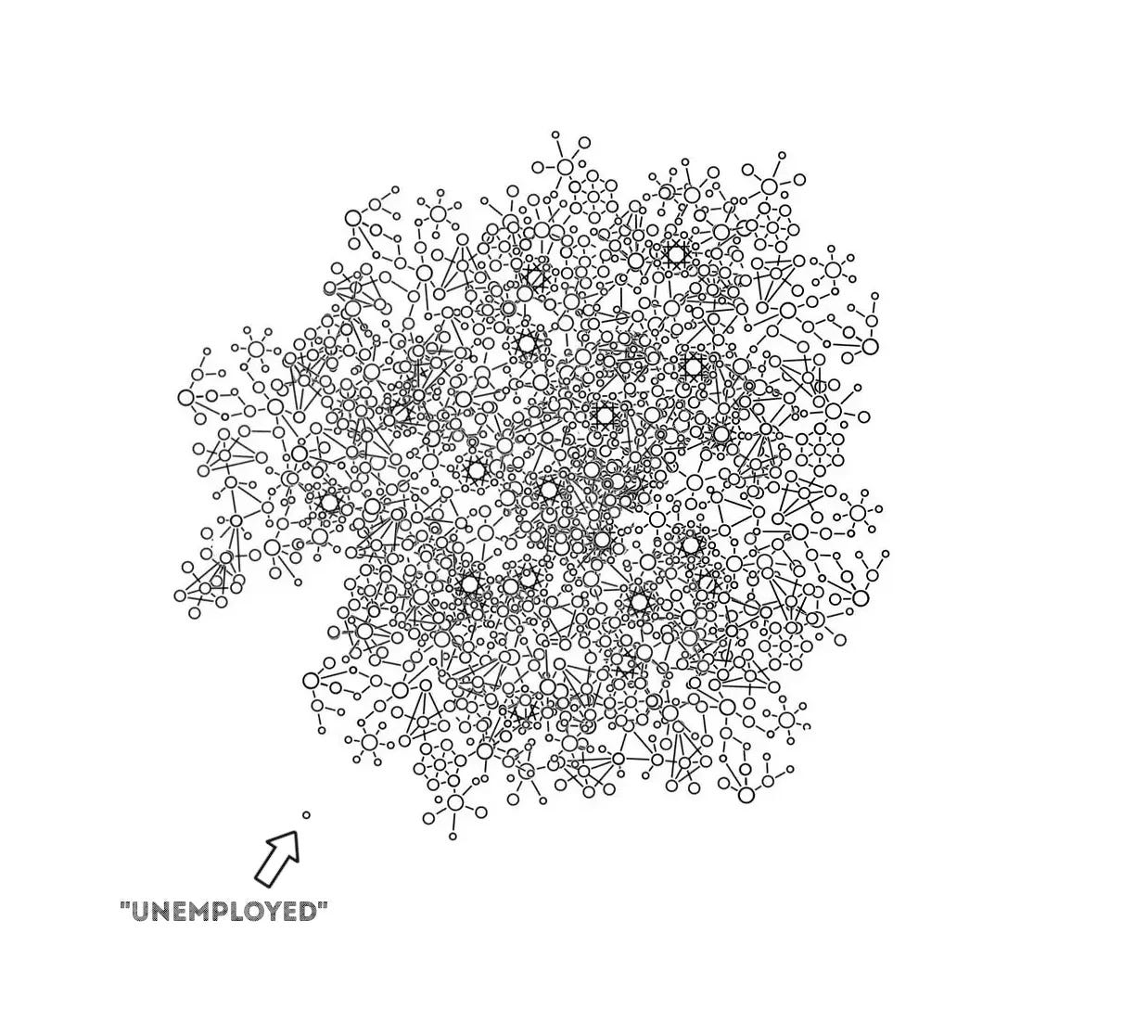

The reality is that you’re never alone in our economic system, and everything around you would dissolve if you were, but it’s not stupid to behave as if you’re detached and alone in this structure, because it often does make you feel alone. After all, you’re forced to compete to get into it, and to stay there once in. What’s an ‘unemployed’ person but somebody unplugged from their life support system?

If they stay unemployed too long - and have no people who can help them - they might end up as a homeless person, who in many ways is pretty individual because they’re more authentically cut off, having less access to (and dependence on) others. This is one reason why truly destitute people often don’t give a shit about societal rules, because it’s not like the society provides for them in any way.

Fear of that destitution, though, can spur certain forms of libertarian thought. That philosophy often tells you that the only way to overcome the waves of insecurity in our economic mesh is to carve out your own destiny and fortify yourself in your own private island.

This doesn’t always have to involve denying interdependence: some forms of libertarianism allow for a romanticised ‘communistic’ element, in which they imagine each solo person cheering each other on to mutual individualistic gain. In general, though, libertarian individualism is a self-help story that many people use as a coping strategy. If they tell it to themselves enough, they might authentically start to believe that they actually are a lone individual in a ‘dog eats dog’ world.

In many ways this is predictable, and I don’t judge people who end up telling themselves these stories, but doing so will affect other stories they tell themselves. Libertarian individualism is part of a bigger paradigm, a network of ideas that hold each other into place.

You’ll notice, for example, that your inner libertarian side will find itself weirdly attracted to the rhetoric of gold and Bitcoin. That’s because that rhetoric is part of the same paradigm expressing itself in a different way. Let’s start to pick apart some of the strands in the paradigm, to show you how they’re wound together.

The starting point

If you start by imagining that the economy is a collection of individuals who choose to trade, you’re implicitly making three linked assumptions:

That an individual is a real phenomenon. You have to believe that it actually is possible to exist apart from others

This in turn implies that you believe that everyone is potentially self-sufficient

This is turn leads to the belief that the self-sufficient individuals are motivated into making connections with each other by choice, not by necessity

It’s a bit like imagining that a cell can survive independently of tissue, and that tissue must therefore be the voluntary creation of independently motivated cells.

Let me introduce some nuance here. Many people will only use this as a background image - a primal hypothetical starting point. They’re aware that it isn’t actually real, but they proceed as if it could be, like a useful fiction.

This is very common in the history of ‘classical liberal’ thought. For example, social contract theorists (e.g. Thomas Hobbes and John Locke) used this to explain political arrangements. They imagined a bunch of individual people (cells) coming together to make a contract to create society (tissue), as if they could break back into individual cells if the contract was broken.

This fiction does have political uses. For example, it could be used to attack predatory absolutist monarchs, or feudal lords, by insisting that the individual ‘cells’ that created the body of the state had individual rights.

That said, no person in the world has ever actually experienced the thought experiment used to create this model. Nobody has ever actually found themselves as a pure individual ‘cell’ that strides forth to ‘create society’, while insisting upon various rights as a condition of doing so.

You can, however, understand why this belief might take hold more strongly in certain contexts over others. For example, if a former Polish peasant arrives in the USA in the late 1600s, having detached themselves from some previous feudal setting, they will indeed feel relatively more free to form something new. But even in those limited contexts, these people are just temporarily detached, like cells recombining into a new formation with slightly looser bonds. They have no real ability to stay fully detached.

The imaginary fully detached individual, though, became an archetype in the field of Economics. That discipline imagined that solo agents used their solo rationality to voluntarily come together to build markets (which are a subset of society). The background vibe is one of individuals who have the option, but not necessity, to interact, and whose thoughts are unaffected by others (i.e. the detached economic agent isn’t woven into a pre-existing culture that moulds their perceptions, beliefs or sense of what’s normal). They’re driven only from within, and everything within is ‘self built’ from within.

Economists nowadays will protest that they’ve nuanced the model with fields like behavioural economics (and there are ‘heterodox’ versions of the solo individual story used in sub-branches like Austrian Economics), but the background imagination of detached individuals remains embedded into the foundations of the field. So, let’s imagine each ‘cell’ as an island on its own, and follow this illusory vision of solo independence to its logical conclusion.

Step 1: ‘Every person an island’

Let’s imagine you’re on your island. Somehow you’re a fully grown adult, and you have your body and mind which you use to produce stuff to survive. It’s like you have your own internal power supply - your energy, skills and wits - and stuff that springs out of it. Crucially, you’re not in any form of debt or obligation to others.

Step 2: I spy another island

From your island you can see another island. This is another individual, using their own labour and wits to also produce stuff. They’re also not in any form of debt or obligation to others.

Step 3: The barter

You spy upon that other island, something that could benefit you. You want the individual to give it to you, but they’re self-sufficient, and have no obligation to interact with you, so have no necessity to act. So, you must appeal to their self-interest, their potential for gain. You must dangle something enticing in front of them to induce them into action.

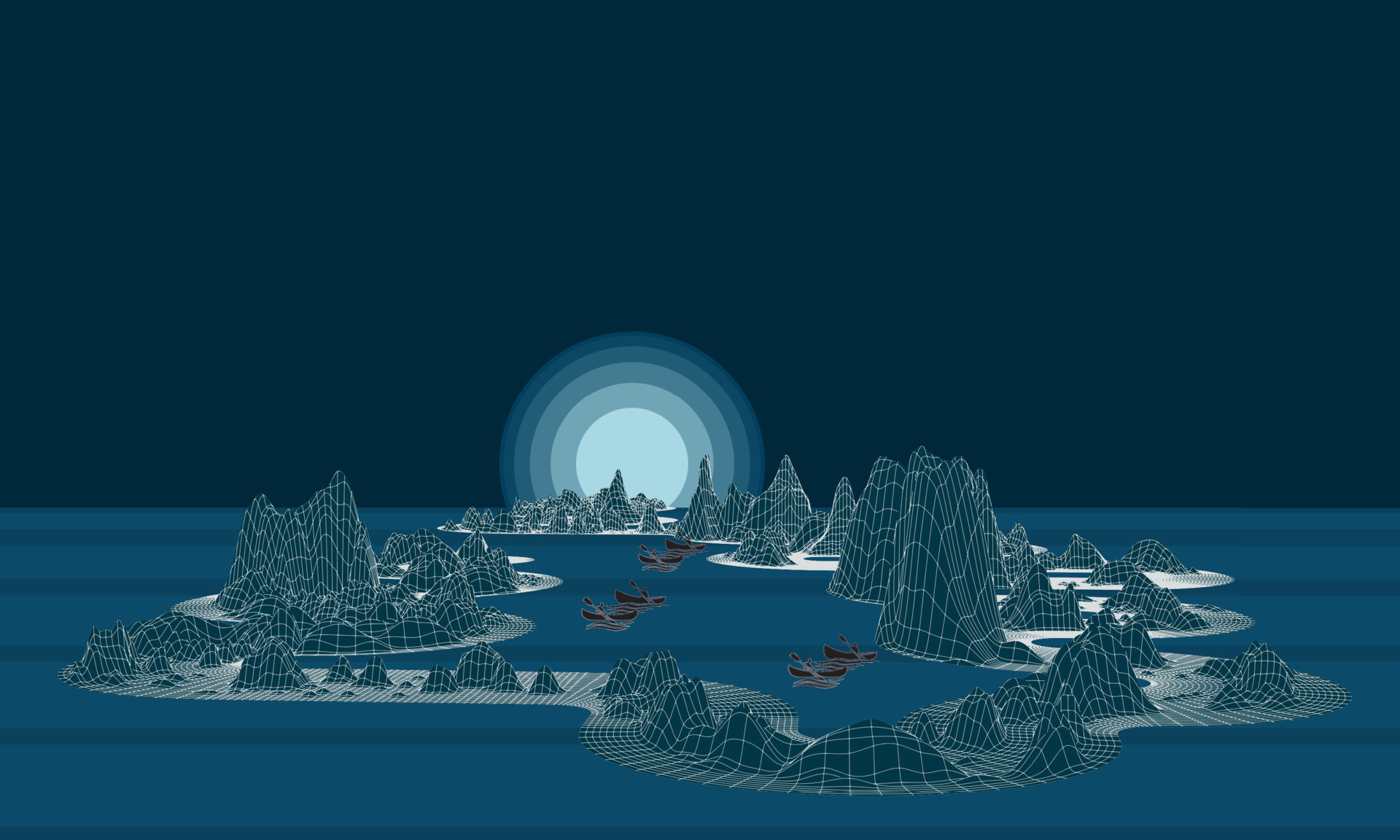

Here’s what you do. You paddle out into the no-man’s water between the islands and call to the other, showcasing what you’ve produced. Upon seeing it, they get into their canoe and paddle out to inspect it. This is the basic libertarian imagination of ‘the market’.

The goods are bonded to their respective individuals through property rights, but as you draw closer, the temptation for the other thing weakens the bond, allowing it to potentially break. That said, if you want too much of what the other has, relative to what you’re prepared to give them, they back away. If you want too little, they spot an opportunity for unequal gain. If you want the exact right amount, you’re in perfect equilibrium: equal mutual gain.

So, your boats come together in an unstable moment, and the respective goods detach and hop over to the other boat. This is the Barter.

Having induced each other into action and having bonded to your new good, you can back away, exit the relationship, and row back to your ‘home base’ solo island, returning to a state of no obligation. Now you can use the stuff you’ve gained to build a bigger island.

Step 4: The archipelago forms

There’s more than one other island though. In fact, there’s a whole collection of solo individuals beavering away on separate islands producing stuff using their wits and labour, all with no obligations to each other. Let’s call this collection of islands an archipelago.

Let’s review this picture: we have solo islands in close proximity, almost together but fundamentally apart. As noted in Detachment Theory, this vision was used by Margaret Thatcher when she said ‘there is no society, there are only individual men and women’.

It was a weird thing for her to say, given that she was prime minister of the UK, a defined political body with laws and rights (and a monarchy for that matter), but what she was trying to imply is that the primal reality of the world is a state of detachment, and attaching yourself to society is something optional and secondary.

She’s imagining that the islands have chosen to forgo their existential isolation and live in closer proximity under common laws for their personal gain (aka. social contract theory). She wants to insist that society must be in the interests of the individuals if it is to be a reality. This is the libertarian view of social arrangements more generally - people always need to be induced into staying in proximity.

Step 5: Money as a permanent inducement for temporary trade missions

Where does the story go from here? Well, as the islands become aware of each other and recognise their common existence in proximity to each other, they send out their canoes to create those moments of barter in the water.

This, though, is imagined to be complex and frustrating, because each specialises in one thing and not everyone always wants it. So, if they spy personal gain upon another island, but cannot induce that individual into action by dangling their goods in front of them, their personal progress is hampered.

Everyone experiences this blockage to progress, and so a common need arises to have some unblocking agent, something that’s guaranteed to act as an inducement every time that two canoes meet out in the open water. This is how money is imagined within this story. It’s supposed to be some special good that allows for consistent interaction between individuals seeking mutual gain.

Notice that you can build this story from your armchair, without ever looking at actual monetary systems. It’s an a priori deduction from the opening assumption of solo islands. This is exactly what Adam Smith did, and also William Stanley Jevons (the pioneer of modern mathematical economics), who noted that:

The earliest form of exchange must have consisted in giving what was not wanted directly for that which was wanted. This simple traffic we call barter… but to allow of an act of barter, there must be a double coincidence, which will rarely happen. A hunter having returned from a successful chase has plenty of game, and may want arms and ammunition to renew the chase. But those who have arms may happen to be well supplied with game, so that no direct exchange is possible.

He then uses this to explain the emergence of money, but notice the telling armchair phrase ‘must have’. He’s literally sitting there in his English office in the 19th century, idly speculating from first principles (somehow, somewhere, a strange society exists, in which separate solo hunters trade arrows and meat with each other, rather than…. ya know… being part of a collaborative hunter-gatherer band).

Anyway, having done this move in their mind, a person with this worldview must then find a way to describe the real world specifics of how this hypothetical money will actually form. There are two basic strategies used here:

The thinker might imagine money emerging out of some widely desired good - something that’s consistently wanted and which becomes the most tradeable commodity. Austrian Economics uses this in their ‘regression theorem’, but these styles of argument are common in mainstream economics too

Alternatively, the thinker can imagine a ‘social contract’ resolution. The frustrated solo islands decide to put aside their individual rationalities, and come together to choose some arbitrary unit to resolve this collective blockage to their individual pursuits. They agree that some common thing must be chosen, and that everyone must uphold a collective belief in this for the sake of their individual interests. This version of the money story turns up in statements like ‘we’ve all just agreed to use money’, and ‘money is just belief’.

Both versions of the story view money as a commodity, with the first being a real commodity and the second being a ‘fictitious commodity’ created through an act of imagination. In all cases, though, the background image of the separate islands, and the two canoes meeting in acts of barter is always there, along with the belief that both things being handed over must always be inducements: both must always ‘contain value’ to appeal to the individual self-interest of the two people. All exchanges then, are ‘value for value’, with one person getting some valuable new thing to build their island, and the other getting a valuable money commodity - either real or fictitious - guaranteed to allow them to get some other thing from some other island in future.

The money commodity takes on a social character, exemplified in statements like ‘I accept money because others will too’, and this is where the vision gets all vague. That’s because it’s uncertain as to whether it’s the money itself with the value, or the future things that it can induce from others that has the value. More often than not, though, this will just be glossed over, and the distinction won’t be made. This, however, leads to some other intellectual quirks:

Given that the basic background image is everything is a commodity and every trade is barter, money is just seen as a commodity that’s easier to barter than others

This, though, means a person can’t make a distinction between monetary price and value, because - well, everything is a commodity with value and money is just a special commodity, so a monetary price is just one commodity’s value expressed in terms of the value of the special commodity

This also means they’ll imagine that everything can be priced in everything else

(Side note: funnily enough, this thought structure was also used by Karl Marx, but with some different background assumptions. If you want me to write about that, let me know in the comments).

The Archipelagoan ideal of money

So, belief in the Archipelago of Individuals leads to a basic story of what money is - a special commodity - but also to a particular idea of what money should do. It creates a series of functional descriptions in which the special commodity is described by an end purpose derived from the opening assumptions.

According to the hypothetical model, money is the thing that must facilitate trade between the individual islands - it must be a medium of exchange - but to do that it must contain value - it must be a store of value - and if it can consistently maintain that it can become a stable unit of account, the thing used to price all other commodities.

To fulfil this ideal role, though, it must have a series of other features. It must be easily transportable, long-lasting, and dividable. Given that this is a hypothetical series of features a hypothetical ideal money is supposed to have, people who use this model must then map it onto the actual history of observed money in society (i.e. what money has been, rather than what it should be).

Typically, then, in the libertarian-tinged imagination, the history of gold looms large, because it’s comparatively easy to shoehorn into the model. They’ll see evidence of historical use of gold, and then imagine that it must have been used because it most closely resembled the hypothetical ideals that emerge from the hypothetical starting point: individual humans either naturally saw the value in gold, or - in the social contract version - were able to come to an easy agreement to use it as an abstract unit, because it had enough of the a priori characteristics required. So, gold finds itself swept into this position because it satisfies the starting assumptions.

The actual history of gold is different to this though. Not only was gold not the exclusive thing being used for money, but its history is a messy jumble of political machinations, violence and ‘fiat’ processes.

Remember, though, that a person using gold as a character in their ideal story isn’t trying to describe history. They’re trying to make their current paradigm work, and to work it needs historical components that harmonise. This is why you find a bunch of modern people who’ve never used gold dreaming of a past in which it hovers like a Platonic Ideal - an abstract commodity with an equally abstract history that serves as something to be emulated rather than actually achieved.

In this context, gold is serving a function within a paradigm, and to defend the paradigm proponents must explain away inconvenient glitches found in gold’s actual history. For example, upon observing the fact that the most widely used gold tokens all had the faces of monarchs on them, they won’t say something like ‘maybe gold had some fiat component to it’. Rather, they’ll say, ‘obviously the monarchs were simply helping the market by acting as an arbitrator of the weight of the commodity’ (this will also generate anger at ‘debasement’, when the monarch lies about the weight). Upon seeing credit instruments and IOUs, they’ll be tempted to imagine them as secondary instruments backed by gold, or eventually settled in gold.

Quick note: you might sense that I have a different underlying paradigm of thought, and I certainly do. In an upcoming piece I’ll explain what happens to your perception of money when you accept that everyone is not an island. Sign up so you don’t miss it.

The Gold Standard vs. Peter Pan

So, our opening image of solo islands sets up an ideal of money as a commodity like gold. It follows then, that any notable deviation from the ideal might cause alarm. Certain moments in history then loom large here, such as the end of the ‘Gold Standard’, and the moment in which Nixon de-pegged the dollar from gold in 1971.

In this context, it’s actually irrelevant to know the details of those historical moments. That’s because almost nobody who brings them up is fundamentally interested in having a real debate about history. These moments are selected by the libertarian imagination, because - within the paradigm - they mark out a clear break between the concept of money as a real commodity and money as a fictitious commodity.

Put differently, if you’re not running the commodity paradigm in your head, these moments do not jump out at you, and they have a different meaning. Most people, however, are running the commodity paradigm, so they need to make sense of this alarming transition between ‘real’ and ‘imaginary’ money.

To do this, they might go down the aforementioned social contract route and just say ‘well, we once used a real commodity for money, but then we decided to use an abstract unit instead, and as long as we believe in it, it’s real’. This is the ‘Peter Pan’ account of money, in which you see it as a fictitious commodity held up in mid-air through an act of imagination.

This risks collapsing into existential horror at any point, because if a person with a commodity imagination accepts that money isn’t a true commodity, they could feel insecure: Shit, it’s not real. It’s ‘created from nothing’. Peter Pan could fall from the sky at any moment.

This background nervousness is created by the commodity imagination (i.e. if you’re running a different paradigm, you don’t feel nervous about it) but it can be exploited for certain political uses.

For example, it can be used to discipline the observed monetary institutions in a society. When a politician says something like ‘money doesn’t grow on trees’, and demands ‘how will we pay for X’, they’re speaking about states, central banks and banks as if they were dealers in a commodity, rather than the origin point of money.

This is why politicians literally believe the state is like a household that must collect the commodity in acts of taxation before they can spend it. These beliefs are delusions, not realities, but they’re strong delusions held in place by a strong and persistent paradigm that keeps re-spawning itself. That paradigm is hardcoded into modern economics, which continues to speak about money like this. This is something that MMT, for example, sets itself against.

MMT proponents are chartalists, and they are running a different paradigm, so their solution is to accept the fact that money isn’t a commodity, and to embrace that fact. The opposite political reaction, though, is to recoil in moral horror and go hardline on the commodity imagination. If you’re running a background story that says money was once a real commodity, and now it’s an imaginary one, it’s not a big jump to start characterising central banks as the perpetrators of a grand fraud. Perhaps they are imposters, oppressively forcing us to use fake money through the threat of state violence.

Ideal type money for ideal type capitalism

Notice also that our original starting point implies a judgemental attitude towards debt. A person begins on their island as self-sufficient with no obligations, and is supposed to end back at that point. In this context, debt is seen as morally inferior, because it implies an ongoing dependence on others - you’ve taken something from them and haven’t given back. Within this thought-structure, the creditor is seen as most worthy, because they’re the most self-sufficient, but the general attitude is that debt is a secondary phenomenon that deviates from the primary starting point.

This moral judgement can merge with that aforementioned horror about modern money being ‘created from nothing’. In the eyes of the purist then, state fiat money becomes an unnatural abomination based on debt. They imagine a utopia of debt-free individuals, and create an image of true money as a debt-free commodity voluntarily chosen by these free individuals. The money is supposed to be ‘apolitical’. It’s supposed to come from something. It’s supposed to last forever and ‘keep its value’. It’s supposed to facilitate a transcendent system of free trade between free individuals. That’s true capitalism, right?

Wrong. That’s ideal type capitalism, a hypothetical projection that emerges out of a hypothetical starting point which doesn’t exist, which then gets projected onto what actually exists. When the projection doesn’t match, reality must either be shoehorned into it (e.g. ‘mega-corporations that use the US dollar are examples of the free market’), or rejected (e.g. ‘true capitalism would have no corporations or US dollars! That’s crony capitalism we’re seeing, not real capitalism!’)

In either case, actually-existing capitalism doesn’t care about this hypothetical ideal double that’s projected onto it, but people in positions of power can get confused by the projection and find themselves not understanding their own system.

The ideal goes digital

Everything I’ve said above applied before Bitcoin existed. Bitcoin, though, plays well with these libertarian grooves in our neural circuits. It actually has multiple backstories, but its big opening claim was that it represented the platonic ideal of money in an updated digital form.

This means it claims a place in a three-part historical trajectory that goes like this:

Once money was pure and real in the form of gold

Then it was bastardised in the form of deceitful fiat

But a saviour - Bitcoin - has emerged that will return us to the ideal, in which true bottom-up capitalism will prevail

One of the most popular Bitcoin bibles is called The Bitcoin Standard, clearly meant to place it in this historical trajectory.

The vision is one of solo ‘sovereign individuals’ on their digitally-secured islands, engaging in free trade with Bitcoin, but there are few little niggling paradigm inconsistencies. In The Art of Crypto Kayfabe I explained how Bitcoin promoters will change the marketing pitch depending on context: sometimes Bitcoin is presented as Ideal Money, but at other times it’s presented as a dollar-denominated asset that will give you better dollar returns than real estate or shares.

Luckily for Bitcoiners, though, the same starting assumptions that lead to the commodity imagination will also allow them to explain away these inconsistencies. For example, if I said ‘Bitcoin is just a digital collectible priced in dollars’, they can draw upon the ‘everything is barter’ and ‘everything can be priced in everything’ thought-structures we discussed earlier. This allows them to say things like, ‘actually dollars are priced in Bitcoin’.

This is a bit like claiming that a tornado actually circles around a kite, rather than the other way around (or that a car racing along a highway is actually static, and that it’s the earth that’s moving under it). For those metaphors to be understood, though, you need to be running a different paradigm that uses different starting assumptions. The vast majority of people don’t understand that paradigm, so they’re highly susceptible to Bitcoin rhetoric.

Many people experience a ‘conversion’ to Bitcoin, somewhat like a religious experience in which they ‘see the light’. This is because the rhetoric plays into the underlying paradigm that already exists, but puts it into a purer, less contradictory, form. For Bitcoin converts, the token represents the new Platonic Ideal of money, even though almost none of them actually use it as money or experience it as such. If gold is the ideal of the past, Bitcoin is the ideal of the future, so it doesn’t actually matter that it’s not currently used as money, because one day it will be.

Trump’s fractal libertarianism

Many people - regardless of whether they’re into Bitcoin or not - will run some version of the commodity money story by default. This is because of that existential reality of living in a large-scale capitalist economy. It feels like you’re alone, so it makes sense for you to metaphorically imagine money as a commodity used to temporarily bridge isolated individuals.

One of the core moves made by Trump is to play into this sense of isolation. Rather than accepting and coming to terms with the enmeshed reality of a modern transnational capitalist system, he forcefully restates the imagined ideal type - what it’s ‘supposed’ to be like, rather than what it actually is. His brand of populism involves creating an image of small capitalists rising up against crony capitalists (which is powerful enough - at least temporarily - to overshadow the glaring elephant in the room, which is the tech oligarchs that surround him).

Trump merges this vision of bottom-up capitalism with a vision of hardline nationalism, which seems unusual, because patriotism is essentially collectivist rather than individualist in nature. He’s got scope to do this, though, because of the peculiar historical story of the US. Remember that aforementioned vibe experienced by the Polish immigrant arriving in colonial USA - there’s a vaguely libertarian starting point that can be imagined in the country (provided you gloss over slavery etc), so you can generate a nationalist story about individualism.

Crucially, though, the libertarian starting point can actually be abstracted up levels like a fractal. Trump’s core message is always about winners and losers. This originally starts at the level of individuals - I am a winner and my enemies are losers - and then gets scaled to the level of companies - my company is a winner, and my competitors are losers - and then to the level of countries: America first. China second.

In other words, nationalism can replicate the basic structural features of individualism at a nation state level rather than a personal level. It presents each nation as an ‘island’ in tense proximity to all the other national islands in the international archipelago. This dovetails with the Trump talk about deals - we’re being screwed on the deal, so give us a better deal or we’re dissolving the international social contract.

In this context, the ideological agenda of the Trump administration aligns - to some extent at least - with the ideological path of the crypto industry. In the next episode of this, I’ll delve deeper into this connection, and show where the proposed ‘Crypto Strategic Reserve’ fits into this.

See you next time!

I deeply appreciate this psychological analysis of libertarian ideology. You're articulating the anatomy of their psychological framework, the interdependent concepts, talking points, and cognitive biases that enable it to be self-sustaining-- as well as the ambient environmental cues that conduces to this type of thinking. An excellent way to approach politics; we require more good faith psychologization of different ideological tribes in our discourse to untangle this messy, alienated, polarized situation we are in

I am reading Capital Vol 1 and currently on Chapter 3 so would really appreciate a similar piece on Marx's theory of money circulation!