The Global Money System in 10 Pictures

The see-sawing webs that hold the world together, and rip us apart

I’m going to show you our global monetary system in ten images, using two basic visual components: webs and see-saws.

I’ll be leaving out a lot of nuance and detail as I do this, but one of the goals of ASOMOCO is to give you simple scaffoldings that can allow you to catch glimpses of otherwise invisible systems. You can add in all the complexities, nuances and deviations later.

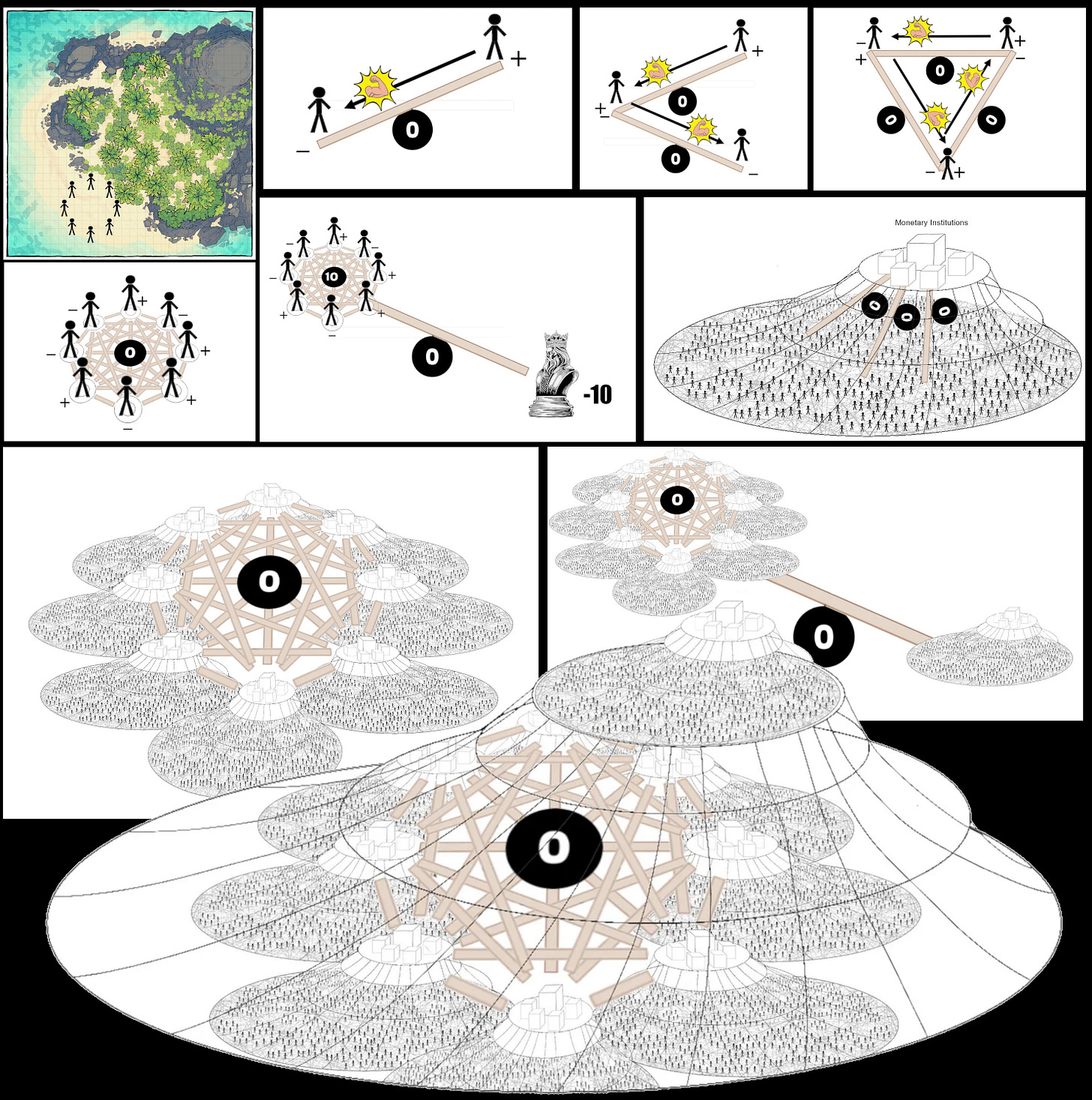

Image 1: Webs within webs

Any economy is always an interconnected web of people who use the planet’s ecosystems to survive, which means any economy is always limited by:

how many people there are

how many things there are for them to work with

So, imagine eight people on a small island 20,000 years ago. That economy will be very small.

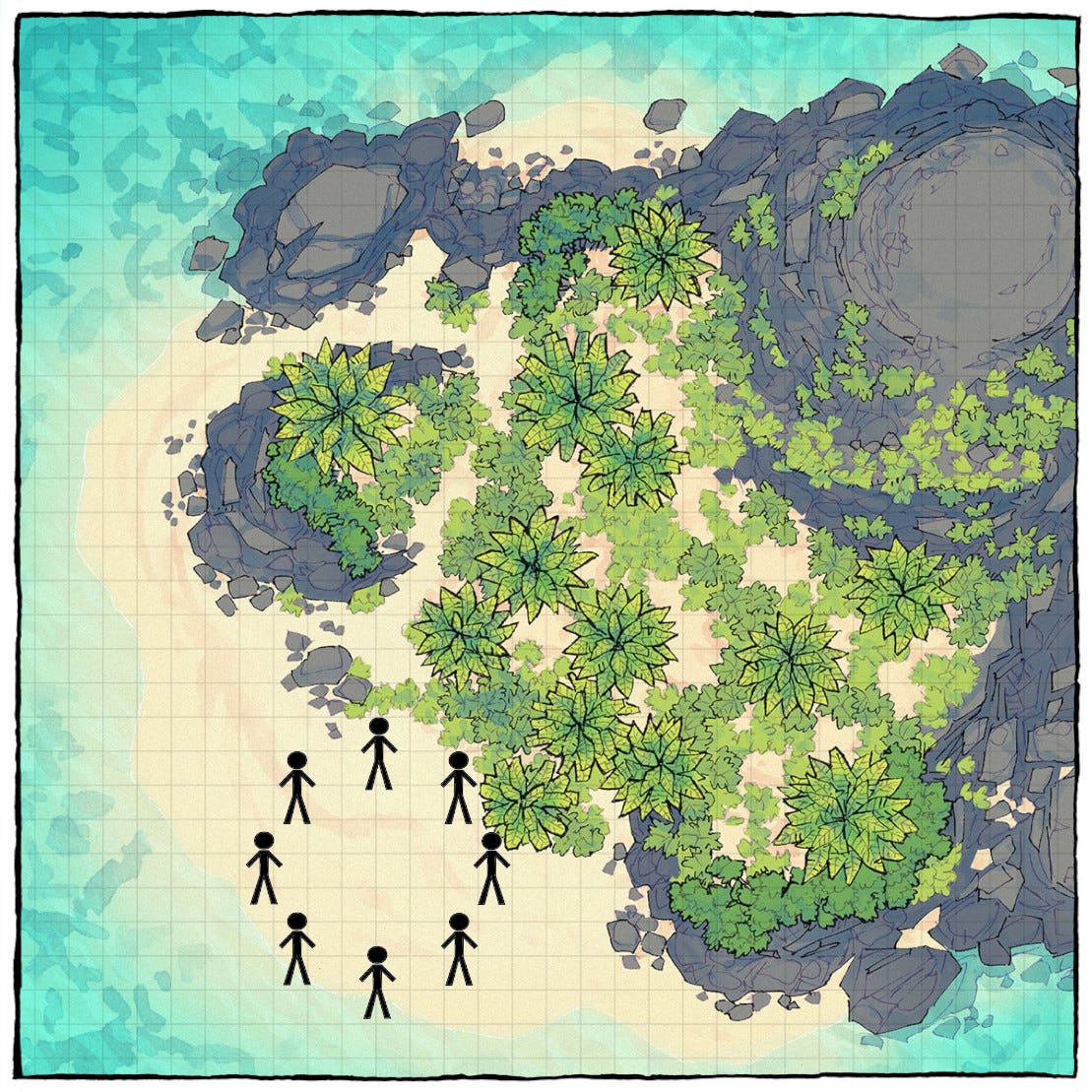

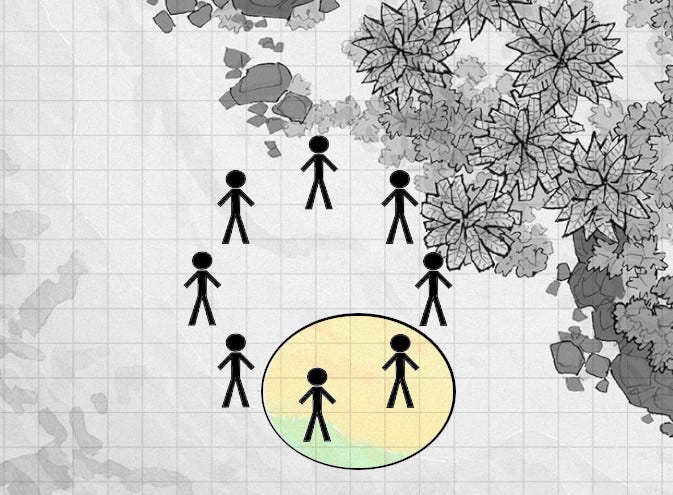

Let’s zoom into that small web. Those eight people form a single system, but that system also contains sub-systems, such as a group of two people within the eight.

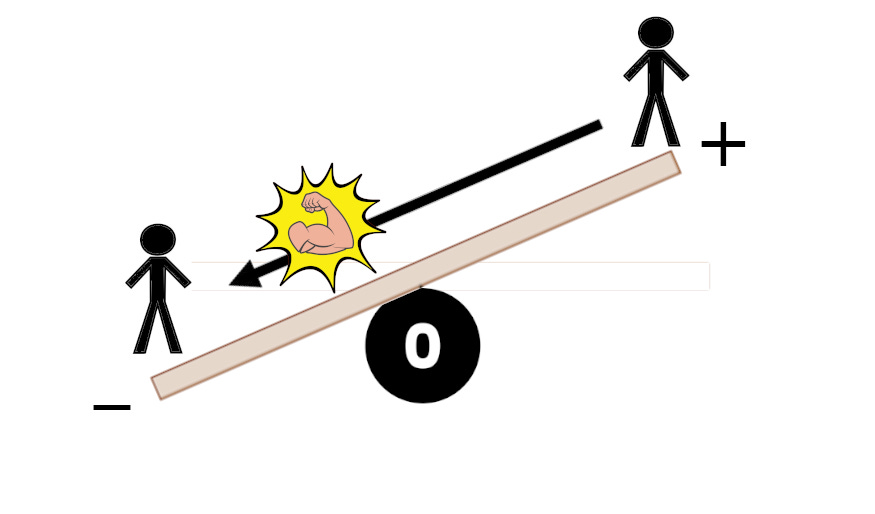

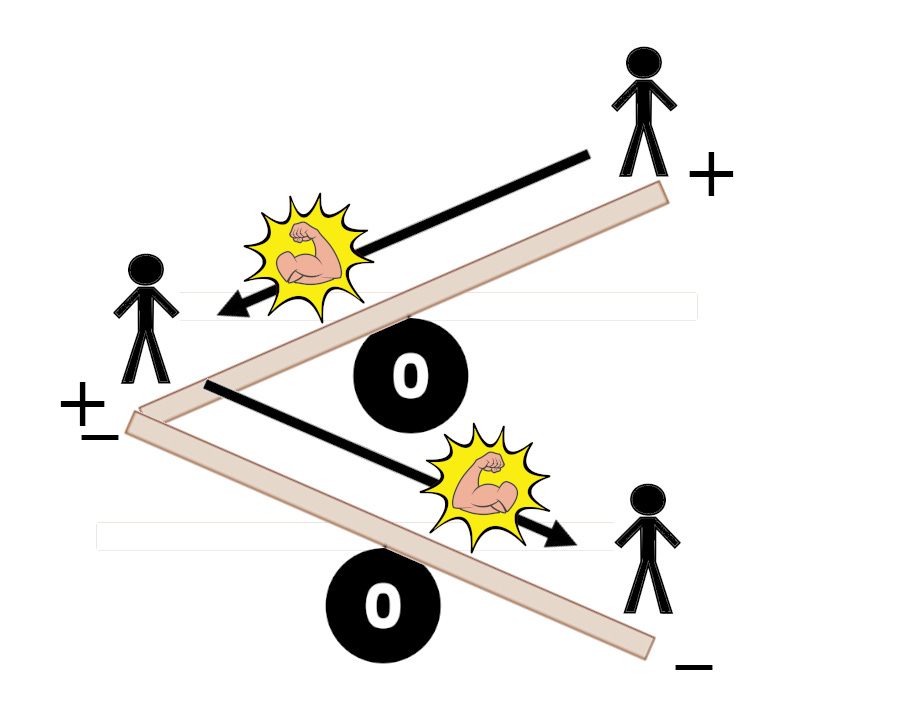

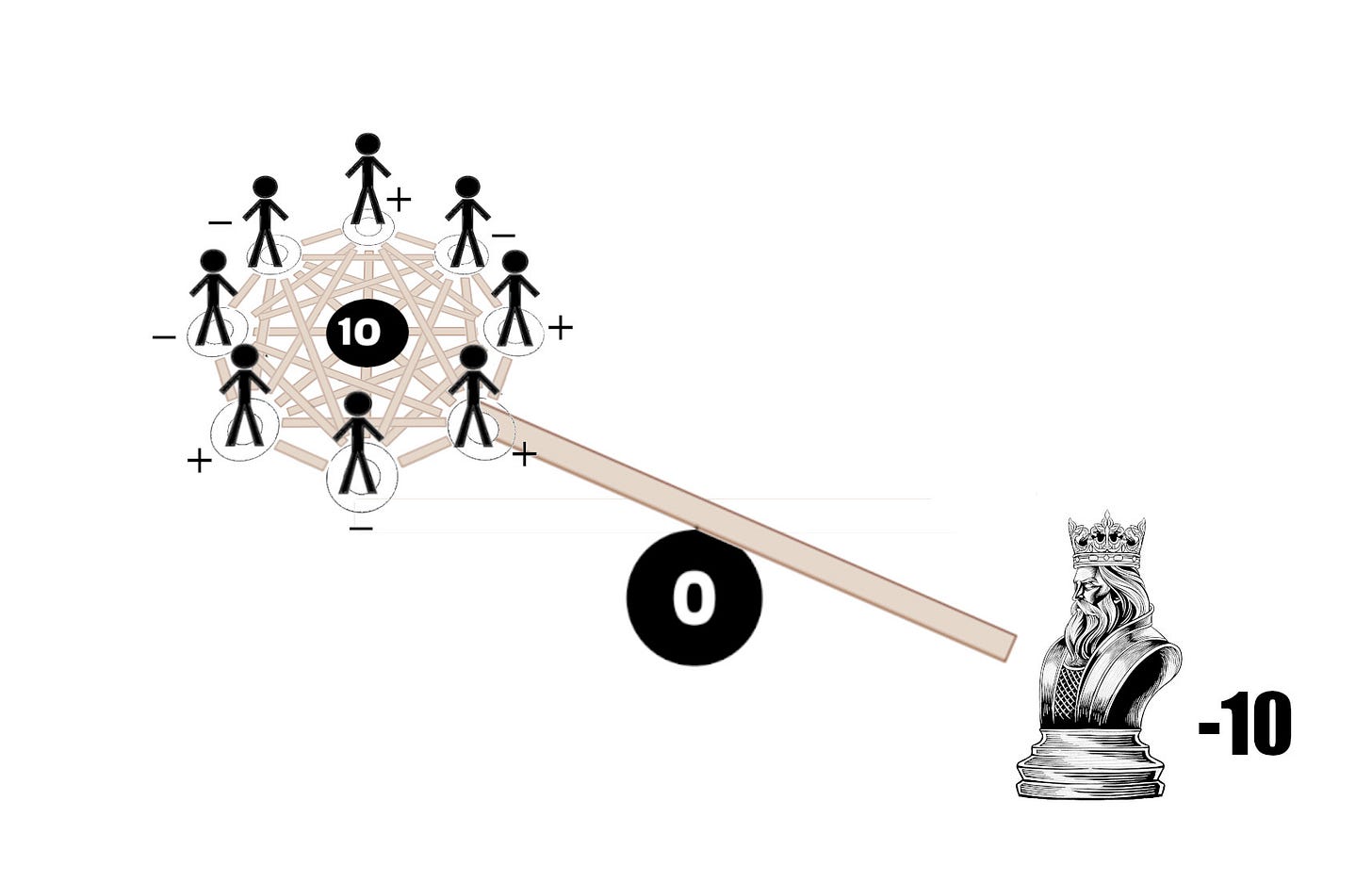

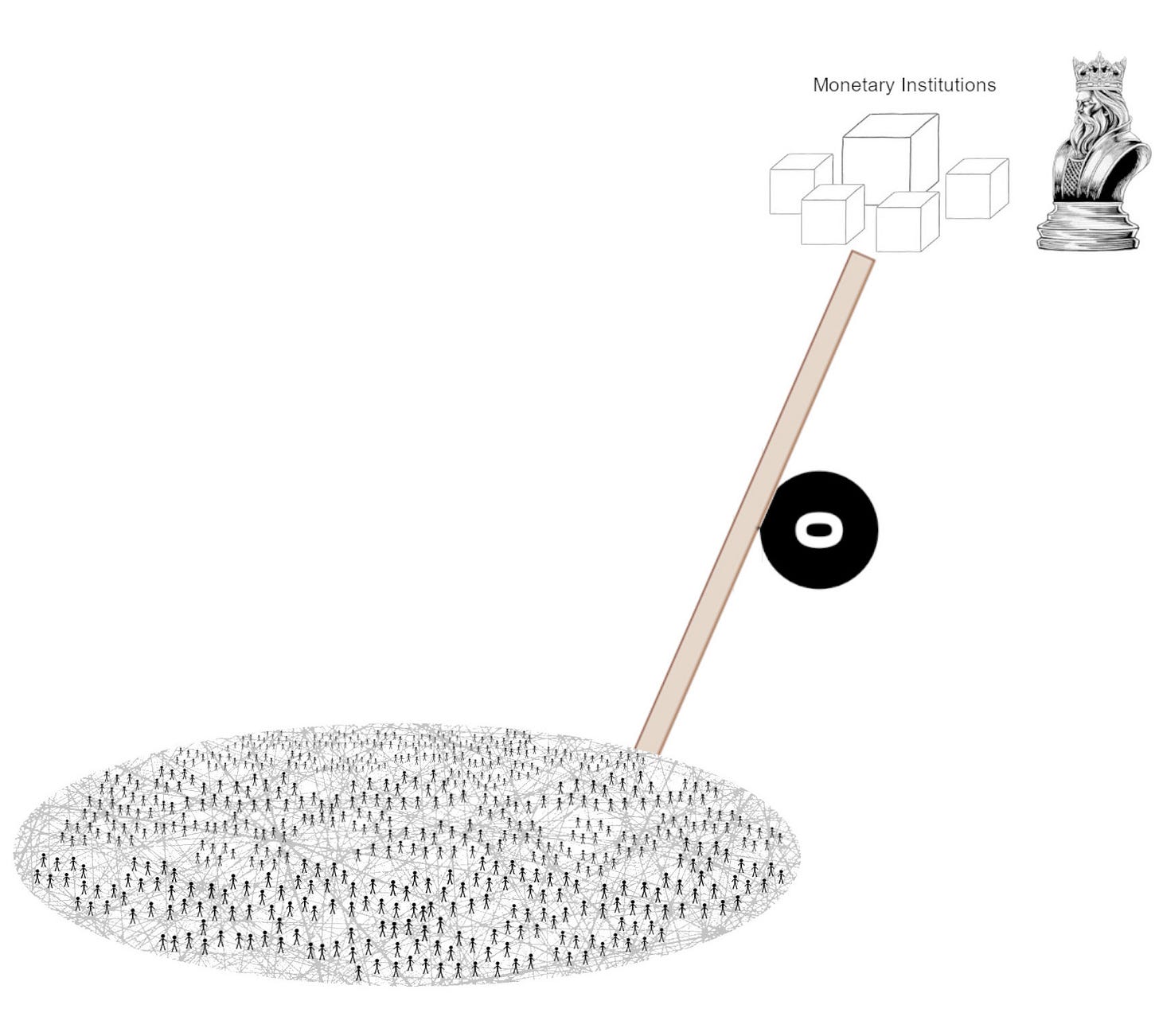

Image 2: A credit see-saw

Let’s focus on those two people. They can move in and out of debt to each other.

When I say ‘debt’ here, I’m not talking about a monetary debt. I’m simply talking about an imbalance in labour.

To understand this, imagine your friend doing a favour for you, like helping you move house. After they do this, you’ll feel ‘in debt’, like you have some obligation to help them at some point. Your friend, by contrast, will sense that they’ve accumulated ‘positive credit’. They’ll feel a confidence that they can call on you at some point. In fact, you might immediately offer them dinner ‘in return’, seeking to partially restore that balance.

‘Balance’ is a good concept here, and it’s why I like to use a see-saw to represent this, with the midpoint represented by a Zero.

Let’s go back to our island. If Person A contributes labour to help Person B, the weight of the labour received by Person B unbalances the relationship, pushing the latter ‘into the negative’, while the former ends up with positive ‘credits’ relative to the latter. One goes below zero, and the other above.

In this context, there’s no formal accounting or exact measurement of these ‘balances’, and being in the ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ is just a background feeling. Both parties simply have a rough intuition that there’s an imbalance, leaving Person B with a sense that they should seek to ‘balance the seesaw’ by returning labour to Person A at some point in the future.

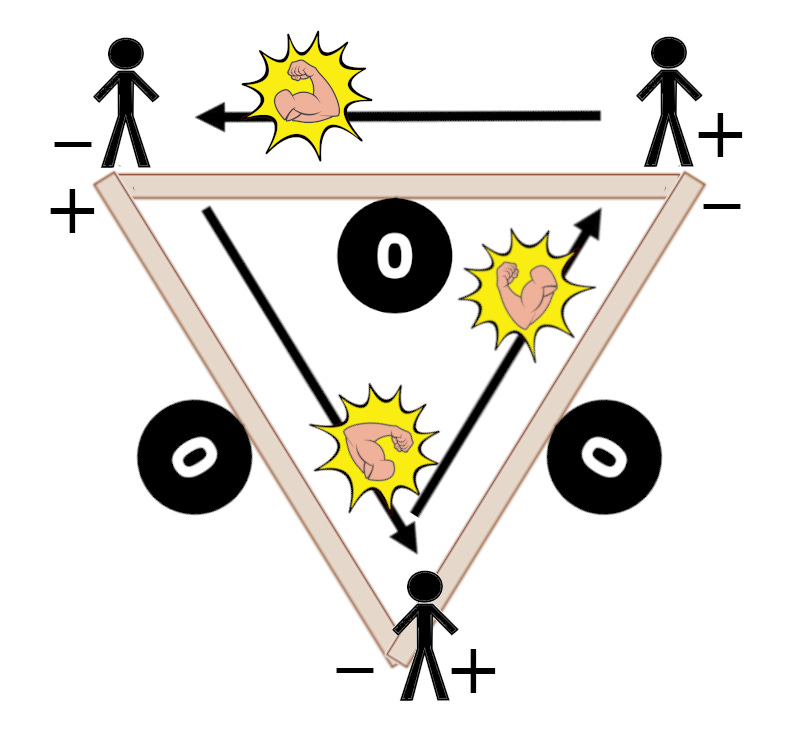

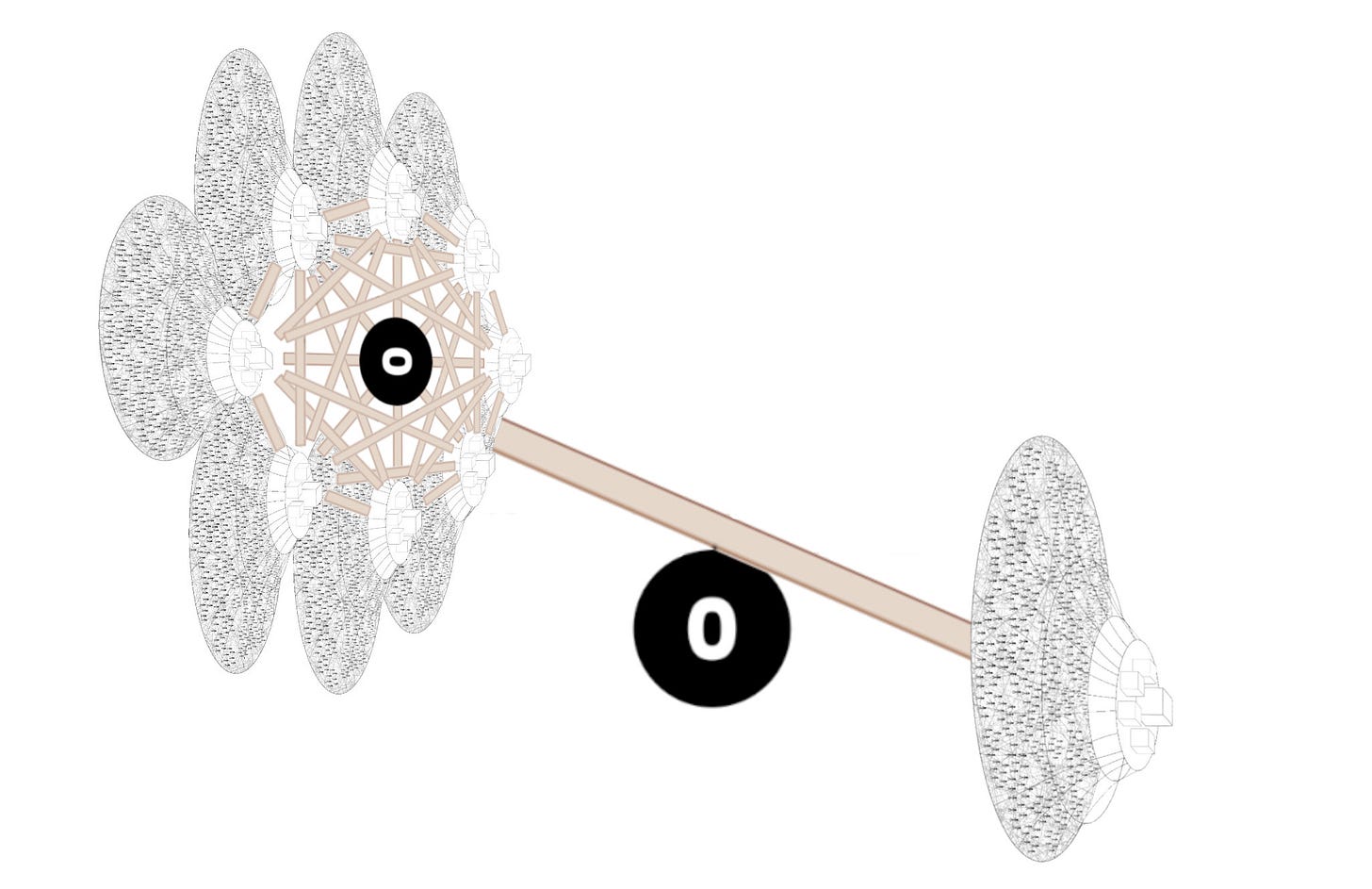

Image 3: Trilateral see-sawing

Let’s now imagine a scenario in which Person B does something for a third Person C, gaining positive credits relative to them.

Person B ends up with both negative and positive credits, so - in the context of this three-person system - they’re in a neutral position, with the positive credits cancelling out the negative. Person A, by contrast, has only positive credits, while Person C has only negative.

Image 4: See-saws in balance

If Person C now does something for Person A, that three-person system balances out to equality again. Each person now has positive credits that offset their negative credits. In a sense, Person C has extinguished their debt with Person B, by extinguishing Person B’s debt with Person A.

Note that we end up with a bunch of stuff produced here as labour moves around, but all the credits end up converging back to zero. Credits expanded, and then contracted, while stuff produced went up.

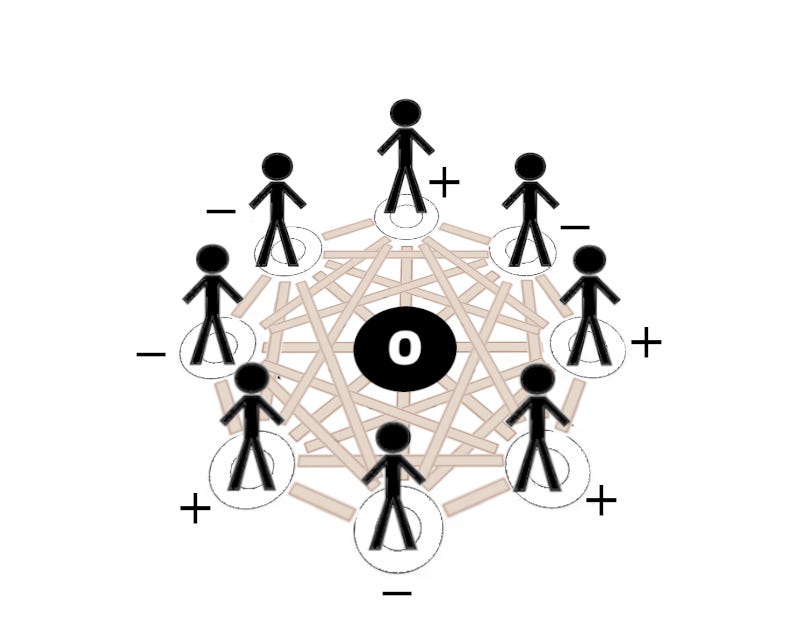

Image 5: A web of see-saws

That three-person sub-system, though, is set within the larger 8-person system, and at this level the possible combinations get more complex. You can have individual people, but also sub-groups, moving in and out of debt to each other. Let’s imagine a web of enmeshed see-saws, a bit like this.

Those positive and negative signs represent people who are in credit or debt (in labour terms) but they always net out to zero, because the only way for an individual or sub-group to go positive is for another to go negative.

Let me introduce two important disclaimers at this point:

In these small-scale scenarios, having ‘positive credits’ generally reflects that you have contributed work, and that you can claim back from others in return. In much larger-scale systems, however, having large amounts of positive credits doesn’t necessarily mean you’ve done a huge amount of work: in fact, in modern systems credits often unequally accrue to those who are in positions of power, or to those who have large ownership of stuff, rather than to those who do lots of work (I’ll expand upon this in later pieces)

Most small-scale communities - whether a family, a group of friends, or an ancient hunter-gatherer band - keep these webs of credit informal. They don’t write down who has done what to keep an exact ‘score’, and seldom expect exact returns. They just keep a rough sense of the ‘balances’ in communal memory, and a rough expectation that reciprocity will play out over time. Much larger-scale systems, by contrast, will begin to formalise the webs of credit

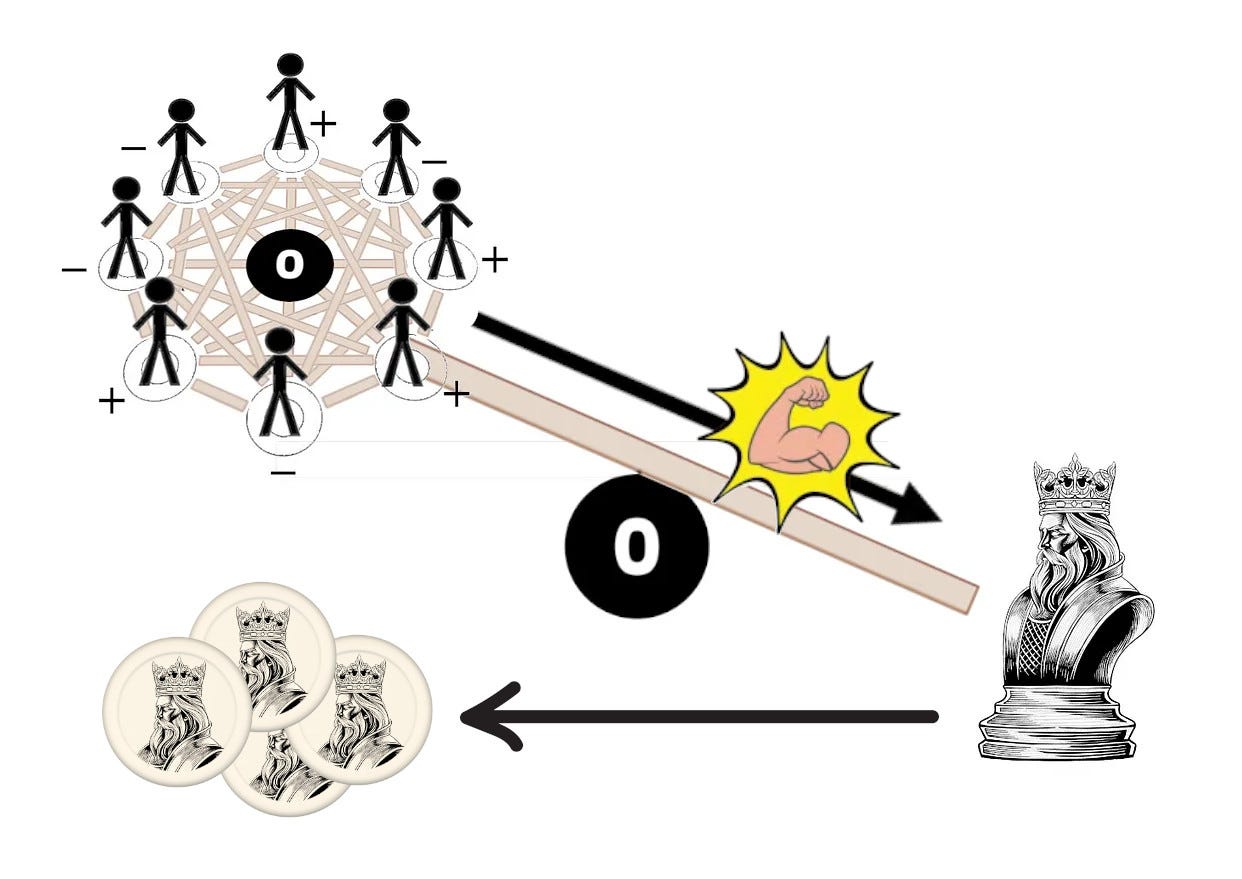

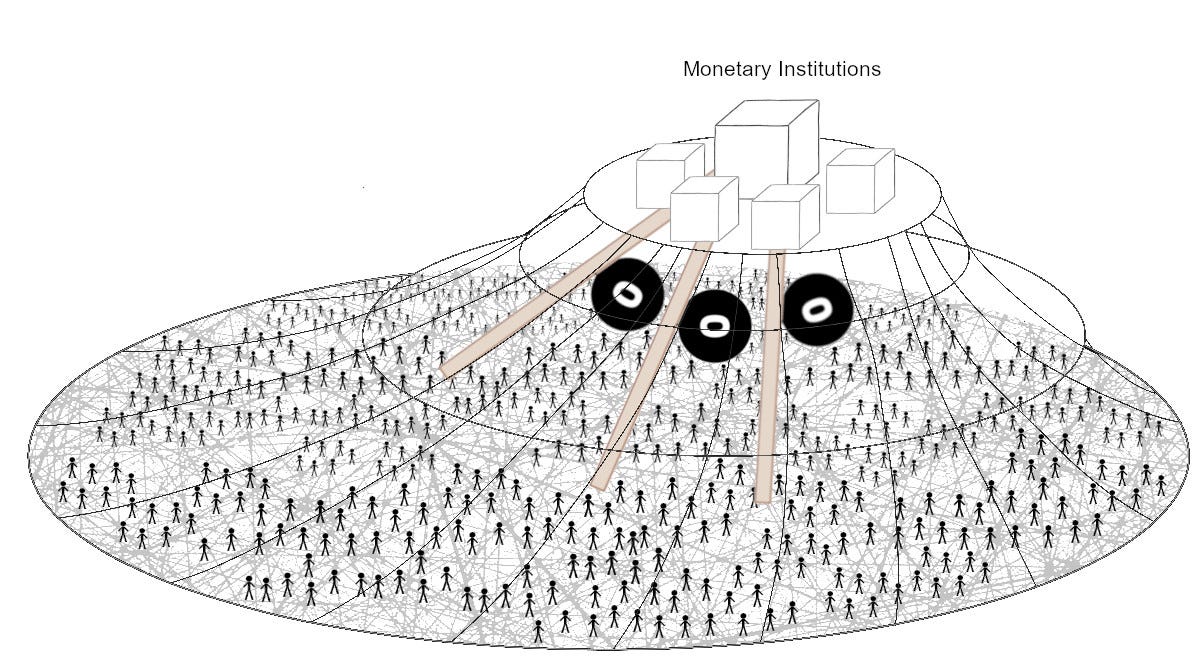

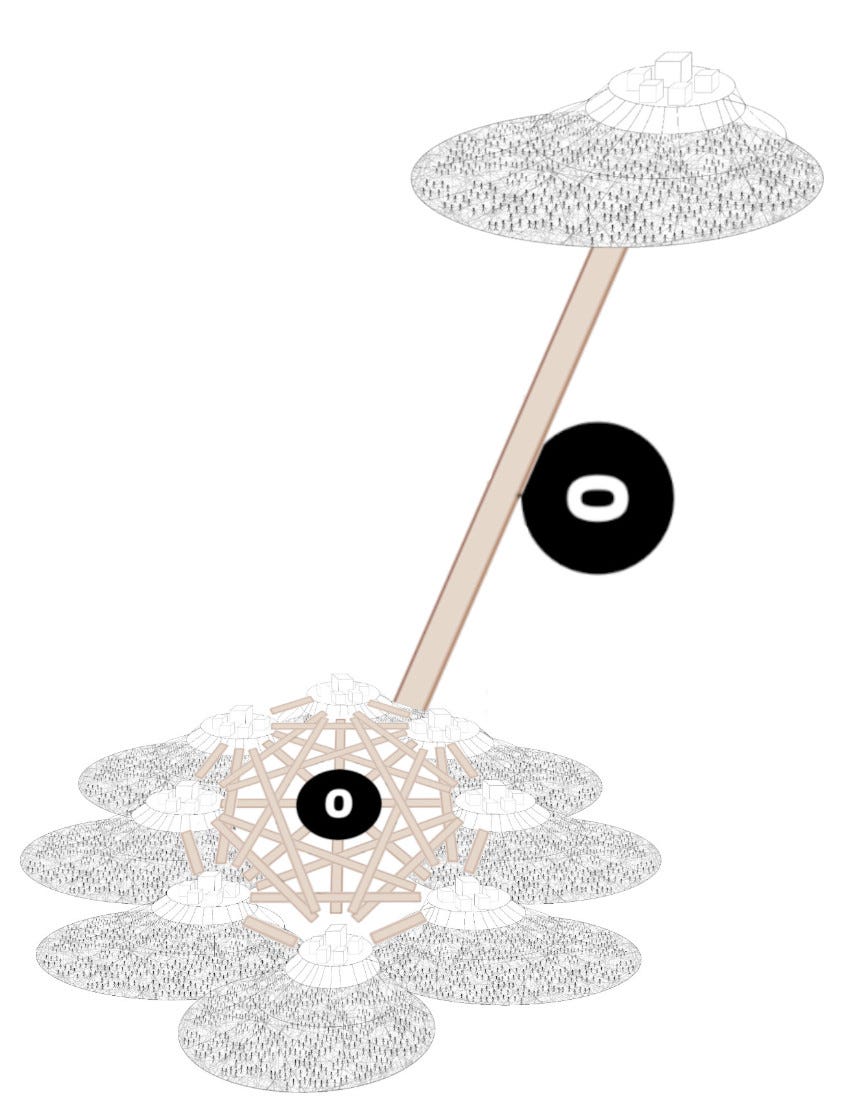

Image 6: A web of see-saws, on a see-saw

Imagine now that our web of eight people has some kind of unbalanced relationship with some external power. Perhaps they are menaced by a warlord and his militia from a neighbouring island.

This warlord demands stuff from them as tribute, threatening violence. Rather than simply sacking the island, though, and thereby destroying the source of the tribute, the warlord uses a more sophisticated method. He issues literal credits - in token form - in recognition of the labour and stuff he obtains from the island.

These credits represent a kind of ‘debt’ that the king owes the people, but he doesn’t intend to ‘repay’ it by transferring labour or stuff back in the future. Rather, he simply demands the credits back at periodic intervals, telling the people that they have to use those credits to neutralise a different type of debt they owe him, which he calls tax.

This is a very crude story that I just gave - and the issuance of tokens by sovereigns in actual human history is far more complex than this - but the basic deal is that people give stuff to the king in exchange for credits that he issues, and then later hand credits back to ‘pay their taxes’, thereby returning them (and moving the see-saw back).

The king is in a position to ‘go negative’, precisely because he has the power of violence to periodically eliminate the positive credit accumulated by the people (aka. “I am more powerful than you, and if you do not hand those credits back to me in tax my militias will hurt you”) but the use of tokens to extract goods and services from the island has some very powerful side-effects, as follows:

The people in our 8-person system continue to have relationships with each other, but as a system they are all in positive credit relative to this external power

Crucially, those positive credits issued by the external power might become the basis for that small network to begin measuring the relationships between themselves. This is the primal vibe of a monetary system

We saw in Image 5 that the balances in the network of eight people net out to zero. What happens, though, when those eight people become one half of a larger see-saw, with a sovereign issuing credits on one side, and the people using those credits between themselves on the other?

Well, their own zero line gets moved upwards. The zero between them gets renamed as a positive number.

Let’s arbitrarily choose some numbers to illustrate this. Let’s say the King is -10, representing the credits issued out to obtain stuff from the network. That means the network on the other side, as a whole, is +10. Now everything nets out to 10 rather than 0 within the 8-person network, because somewhere else in the system, on the issuance side, there’s a -10.

In our everyday experience of our monetary system, we’re like that network of people on the left hand side of the see-saw - we see money credits as ‘positive numbers’ - but all positive units of money actually have a negative counterpart somewhere else in the system. That minus number section on the right hand side is called the liability side of money, and in our modern system it exists in the state, the central bank and in the banking sector.

So, let’s take the image above and modernise each component.

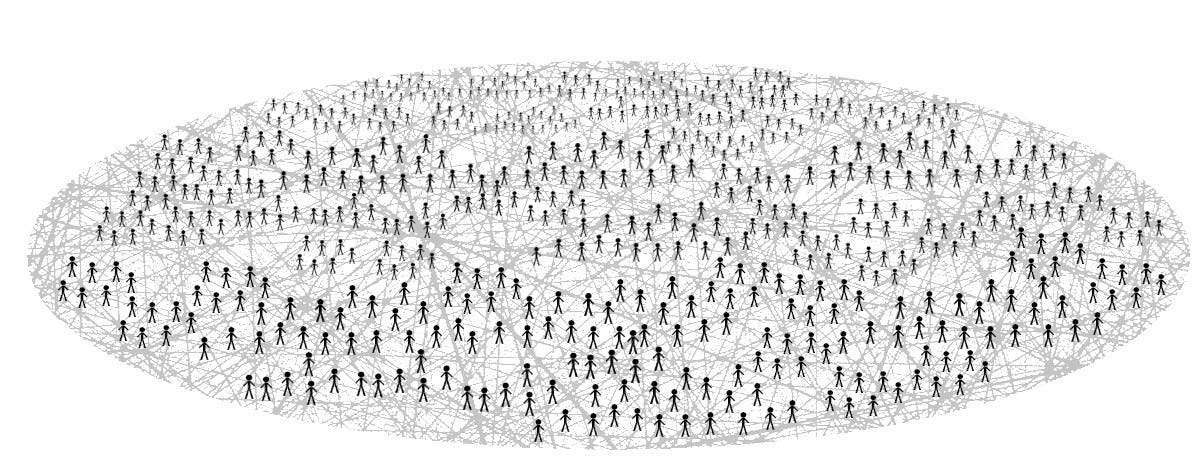

Image 7: Scaling it up

Unlike an island with eight people using informal webs of credit, a modern national economy is a vast web of millions of people. Let’s represent that web like this.

Those lines between the people are intended to generically represent the enmeshed webs of interdependence between people (or the ‘see-saws’ in our earlier 8-person image).

Let’s now represent our ‘king’ in a new form - as a conglomeration of monetary institutions, with commercial banks clustering around a central bank backed by state power.

I’m well aware that I’m glossing over an enormous amount of detail here, but as mentioned, I’m aiming to give you a conceptual model that you can then go fill out.

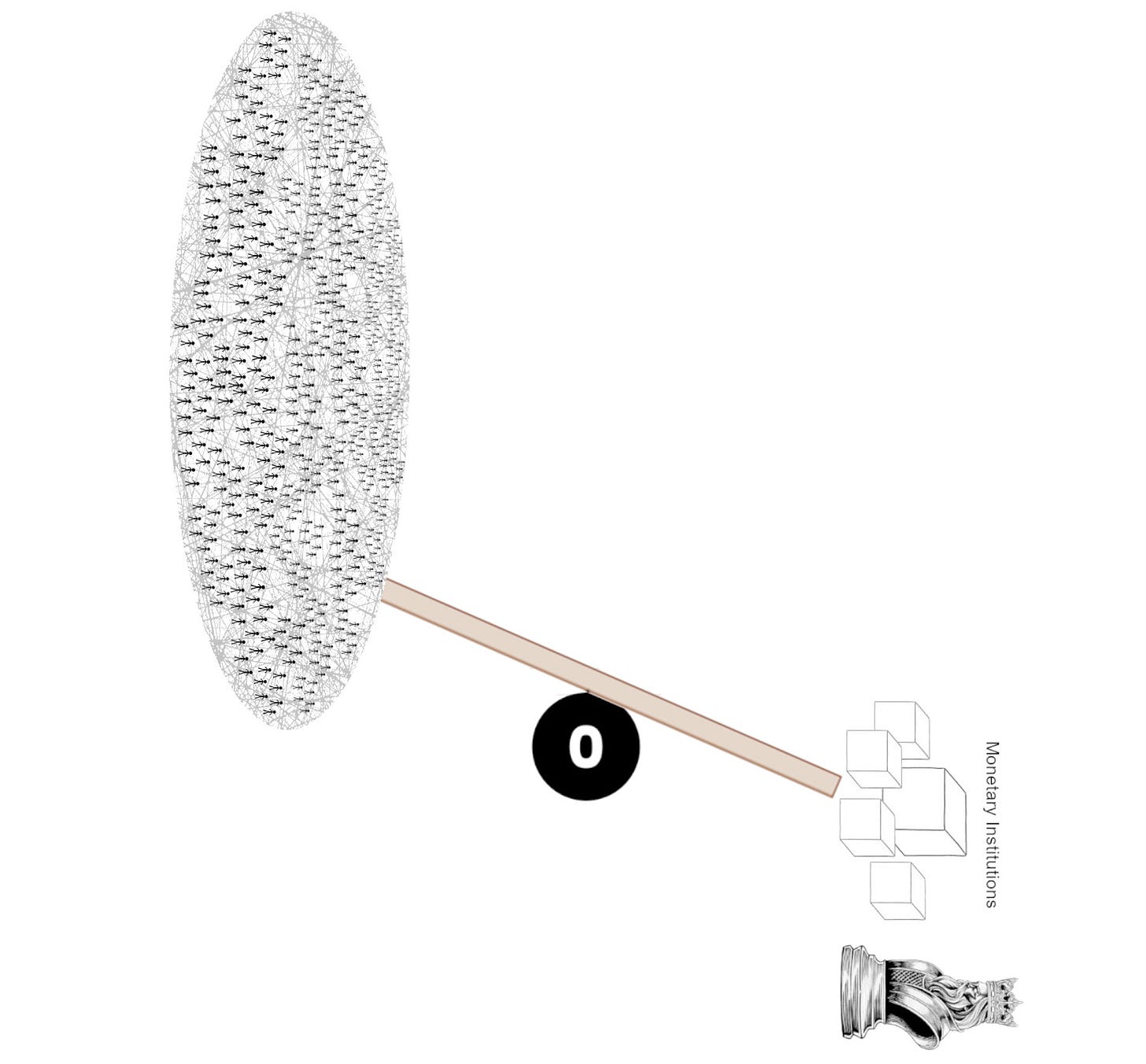

I’m going to represent society on the positive end of a see-saw, with the banking sector and state on the negative side, but I’m going to do it in a slightly counter-intuitive way, as follows…

Now, in your mind’s eye, rotate this image around 90 degrees, so it ends up like this, with the see-saw on a vertical axis rather than a horizontal one.

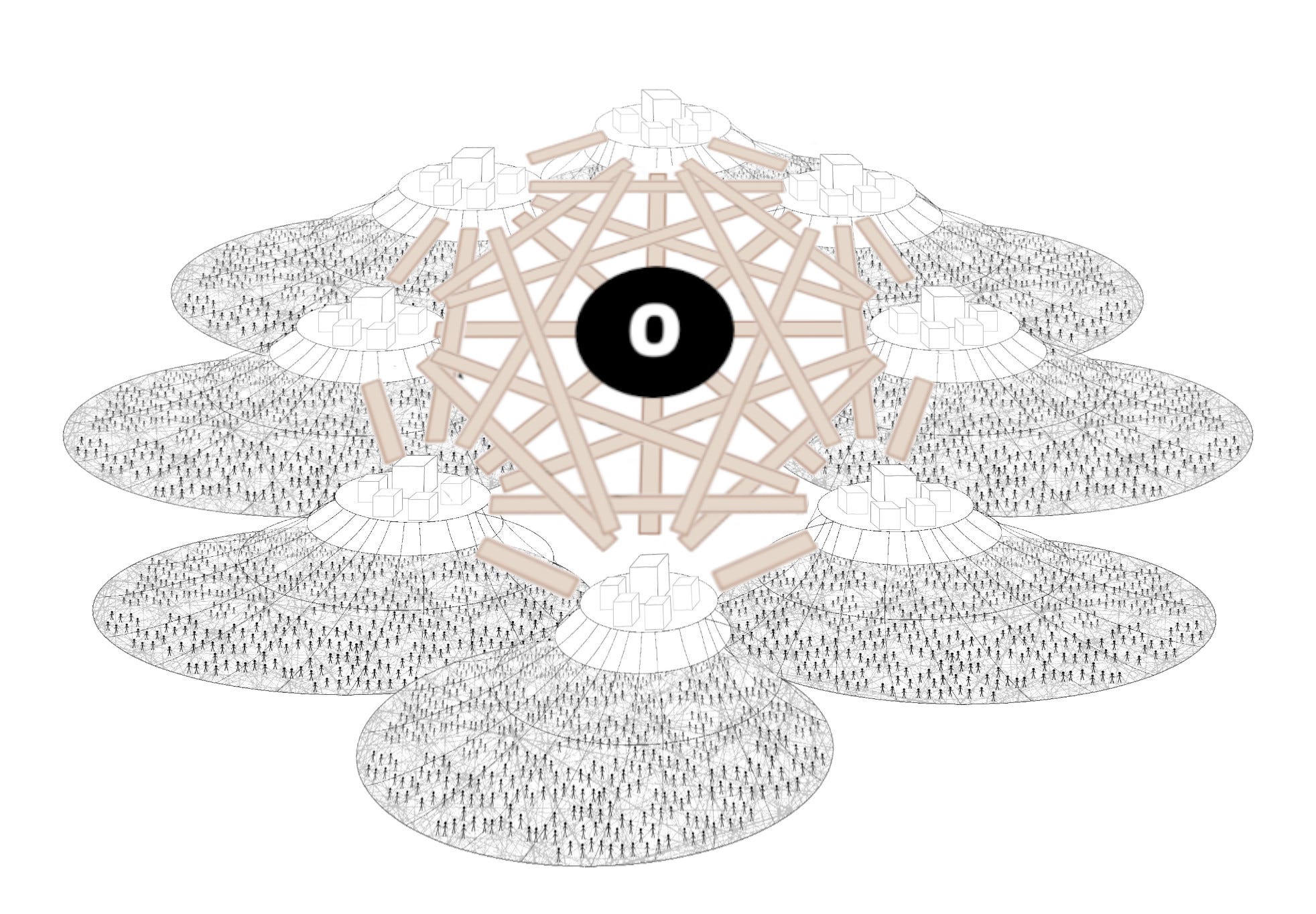

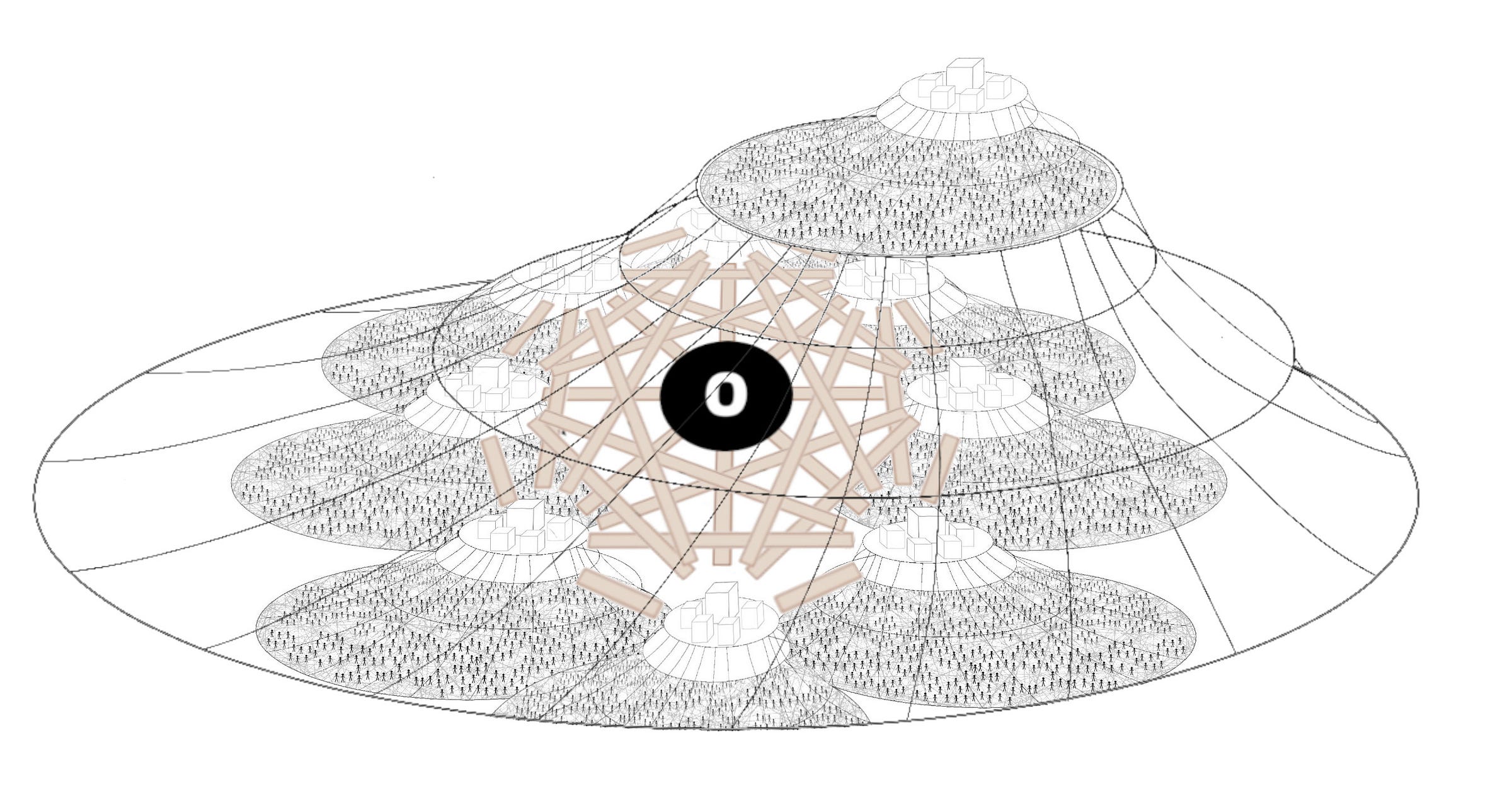

Image 8: Splitting the meta-see-saw

Now, imagine that big see-saw as being constituted by various sub-see-saws controlled by different banks connected into the central bank, but collectively spreading out positive credits like a web across the population…

Ok, so we now have a very rough - but workable - image of our monetary system, with a vertical and horizontal dimension.

On the horizontal dimension at ground level, we have a huge network of people with ties of horizontal interdependence between them. As mentioned earlier, that interdependence nets out to zero, but we’re using positive-number credits between ourselves that come from big institutions. Those positive units of money only exist because there’s a giant hidden negative number that sits in that vertical dimension in the banking sector and state, both of which push those credits out, and pull them back in (to explore the bank element of this, see my recent piece Banks create money, but how do you explain this to the public?).

So, our monetary system is a multilayered hierarchical system administered by commercial banks, central banks, and state treasuries, but it ends up functioning like a giant accounting system that keeps track of the different ‘scores’ people have on that horizontal plane.

Now, in a future episode, I’ll problematize this particular image. Specifically, I’ll start to add in hierarchies of ownership and power, with corporations, billionaires and so on, and I’ll show why their extremely high ‘scores’ do not equate to work done. For now, though, that topic will have to wait.

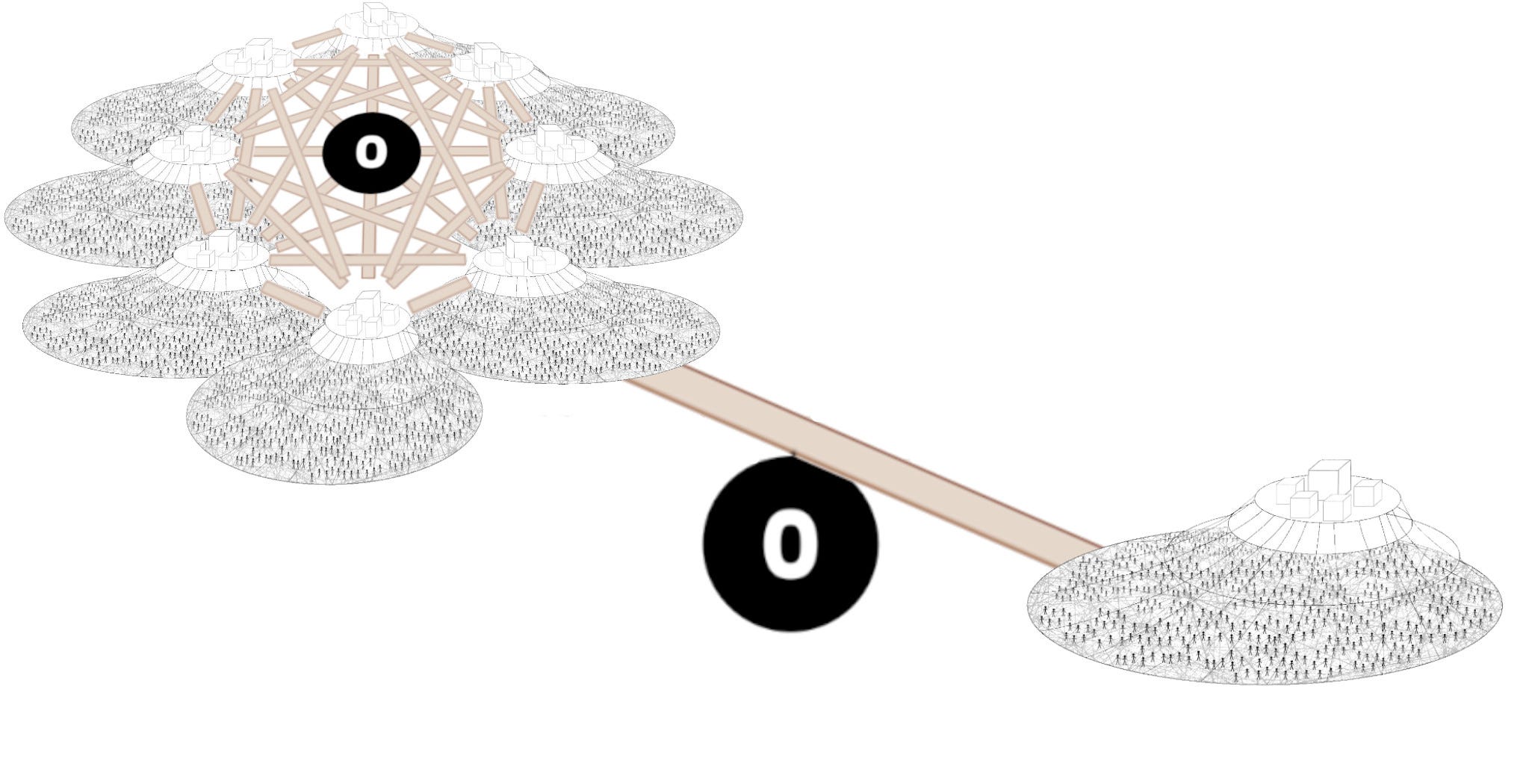

Image 9: The international system

Having created that national image, it’s now crucial to point out that each national economy with its national currency is but one sub-system within a much larger global economy. To view the international system, we have to start thinking about it as a giant credit network of credit networks.

Let’s imagine our eight person island, but now each ‘person’ is an entire country.

The image below shows a whole series of countries with a mesh of see-saws between themselves. They can go positive and negative relative to each other. This is what economists will talk about as ‘trade surpluses’ - when a country is ‘positive’ - or ‘trade deficits’ - when they’re in the negative.

This image will also help you imagine international payments and foreign trade. Choose one random person in one of the countries, and then trace a path through their banking sector to another person in another country. When you pay for goods internationally - for example, when you click ‘buy’ on a website offering goods from abroad - a bunch of banks have to do business with each other to ‘settle’ things on behalf of citizens or local companies.

Image 10: The US dollar reserve system

Having said that, it’s worth noting that a huge amount of international trade between countries actually relies upon them using a single currency between themselves, and that currency is the US dollar. This is what we call the US dollar reserve system.

To visualize it, imagine that network of countries having an unbalanced relationship with the US, and using its credits to mediate trade between themselves.

Let’s now do the same little trick we did in Image 7, and shift the orientation slightly…

And then swing the see-saw 90 degrees to a vertical axis…

And finally, let’s pull those two sides in, to create an image of the US dollar as a kind of ruling monarch of the international system.

This position gives the US certain powers. In fact, it gives it an ‘exorbitant privilege’, an ability to go way more ‘into the negative’ than the average country, as well as a bunch of other special powers, like lower borrowing costs due to high and consistent demand for US dollars.

This image might be helpful if you’re trying to understand a bunch of current geopolitics. For example, for the rest of the world to use the US dollar as a reserve currency, they - theoretically at least - must run a ‘trade surplus’ with the US (i.e. be getting positive US dollar credits by giving the US stuff, and not handing those credits back to the US in exchange for stuff).

This - theoretically - leads to what is sometimes called the ‘Triffin Dilemma’ - the US can choose to maintain its position as the world’s reserve currency and get a bunch of power and stuff from that, but this means it must remain ‘in the negative’, which is something that Trump and his economic adviser Stephen Miran whinge about.

I say ‘theoretically’, because the real world is more complex than this model, and there are other ways for countries to get US dollars beyond running trade surpluses (if you want to get into the technical weeds of that, check out this piece).

Another hot topic right now is the fact that the US - hovering above the rest of the world - is now trying to get private sector players to push out US dollar stablecoins (digital vouchers for US dollars) in an effort to directly undermine the national sub-networks beneath it, and to make the world’s population dependent on the US dollar for even everyday transactions between local people in their own countries. A bunch of politically naive tech and crypto enthusiasts think that’s wonderful for the world’s population, but it’s also an imperialistic play.

Of course, I’m leaving out a shit-tonne of stuff here, like the entire financial system and bond markets and so on. Hopefully, though, this gives you an initial understanding for how that sense of small-scale debt you feel when a friend helps you move house, has vast-scale counterparts in the international system.

Be careful though to add in differences in power when the scale changes, because power alters the nature of debt. Remember that sovereigns and other powerful players often like to be in debt, because it’s part of the structure of what makes subordinates dependent on them. You will help me move house, and you will be grateful for that, for I shall bestow upon you my precious tokens, and you will become dependent on them to survive.

Probably the best distillation of the international monetary system I have ever seen. Great job, Brett!

Brett, brilliant and thank you - you continuously help me understand more & better.

Alongside energy balance (there’s a planet earth involved somewhere), there’s an uneasy balance with “violence” (or maybe we call it a “jubilee”).

I am waiting for the rest of the world to call on (or enforce) the 1 year of “labour” from all 300m+ US citizens, they are “owed”.