The Stranger King of Venezuela

An anthropological lens on Trump's American Colonialism

Paying subscribers can listen to me reading this essay here

Dear readers,

In this essay I’d like to introduce you to the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins’ work on kings, and how it can help us to understand not only the relationship of Venezuelans to Trump, but also the relationship between US Americans and Trump. Sahlins was the doctoral supervisor of the late David Graeber, who is one of my inspirations. Let’s begin with a review of one of Sahlins’ core concepts.

The Stranger King Myth

Reach back into history, and you’ll find mythological tales of the Stranger King repeated across different cultures.

These Stranger King stories have a common structure. They are generally set in some troubled ancient regime in which a local despot rules, surrounded by bickering elites. The despot finds himself challenged by a foreign stranger with mysterious, even supernatural, origins. The stranger is often young, handsome and violent, and has a willingness to bend societal norms (or step outside of them). The despot tries to outwit or outfight the newcomer, but is defeated by their trickery or sheer force. The outsider usurps the power and founds a new kingdom.

There are many examples of the Stranger King myth. Anthropologists have found them in Polynesia, Melanesia, Sulawesi and the East African Rift Valley, and Classicists can find many examples in Greek and Roman mytho-histories. See, for example, this overview by Olaf Almqvist in which he demonstrates the stranger-king credentials of rulers like Aeneas, Pelops, Cyrus the Great, and Sargon of Akkad (even the mythical founder of Rome - Romulus - has a Stranger King vibe).

In fact, dynasties will often seek to trace their origins back to an ancient Stranger King. For example, the 16th century Mexica ruler Moctezuma reportedly said that he descended from a lineage of “strangers who immigrated hither from a very distant land”1.

If we talk about Stranger Kings, however, we also have to talk about the legendary anthropologist Marshall Sahlins (1930-2021), who took time to analyse them. His writing on Stranger Kings began in 1982, but his last work on the topic was a collaboration with the late David Graeber in 2017, in a book called On Kings (you can find an open access version of it here). In it, Sahlins and Graeber note some key features of the Stranger King:

On his way to the kingdom, the dynastic founder is notorious for exploits of incest, fratricide, patricide, or other crimes against kinship and common morality; he may also be famous for defeating dangerous natural or human foes. The hero manifests a nature above, beyond, and greater than the people he is destined to rule—hence his power to do so…. (T)he monstrous and violent nature of the king remains an essential condition of his sovereignty. Indeed, as a sign of the metahuman sources of royal power, force can function politically as a positive means of attraction as well as a physical means of domination.2

In some ways this is a more sophisticated take on the ‘might is right’ concept. The stranger king might be monstrous, but by stepping outside of normal rules, he creates a mystique, a sense that he has access to powers beyond the ordinary world, and this can become a source of legitimacy.

Equally important, however, according to Sahlins, is that the Stranger King enters into some kind of social contract with the conquered people.

…there is invariably a tradition of contract: notably in the form of a marriage between the stranger-prince and a marked woman of the indigenous people—most often, a daughter of the native leader. Sovereignty is embodied and transmitted in the native woman, who constitutes the bond between the foreign intruders and the local people. The offspring of the original union… thereby combines and encompasses… the essential native and foreign components of the kingdom.3

Not only will the woman domesticate the otherwise dangerous outsider, but local elites see opportunities to reform themselves around the Stranger King, seeing in this external power the potential to overcome their own internal divisions or turmoil.

So, while Stranger King myths might involve heroic, violent, or otherworldly power grabs, they aren’t necessarily stories of straightforward conquest. In fact, they are often stories of usurpation, and Sahlins notes that this pattern actually occurs in various, fairly recent, historical situations.

Given their own circumstances—including the internal and external conflicts of the historical field—the indigenous people often have their own reasons for demanding a “king to lead us and to go out before us and fight our battles” (1 Samuel 8:20). Even in the case of major kingdoms, such as Benin or the Mexica, the initiative may indeed come from the indigenous people, who solicit a prince from a powerful outside realm. Some of what passes for “conquest” in tradition or the scholarly literature consists of usurpation of the previous regime rather than violence against the native population.4

This framing of Stranger Kings gives us a more multi-faceted lens through which to view colonisation, because, in the words of Sahlins:

European colonization is often in significant aspects a late historical form of indigenous stranger-kingship traditions… besides Captain Cook in Hawai‘i… there was James Brooke, “the White Rajah of Sarawak,” whom local Iban considered the son or lover of their primordial goddess Keling; and Cortés, greeted by Moctezuma as Quetzalcoatl, the returning king and culture hero of the legendary Toltec city of Tollan.5

The take-away point is that colonists are seldom experienced in black-and-white terms, precisely because they often arrive into the already grey context of pre-colonial politics, with different sections of an indigenous population - with different agendas - seeing in them different things.

At this point it’s important to flag up that colonists always have a vested interest in claiming that they are warmly welcomed by the local population. European colonists, for example, imagined themselves as ‘bringers of light’ on a mission to ‘civilize savages’ living in a ‘primitive’ state of turmoil and godlessness. That said, anti-colonial narratives face the opposite problem, in that they can overemphasise the lack of agency in a colonised population. Sahlins’ discussion of Stranger Kings highlights the ambiguity in foreign takeovers, because the arrival of the violent outside ‘King’ might present opportunities for local elites, who may be prepared to collaborate with, or take a chance on the external power. They may see certain uses in the distant, aloof, strangers, who don’t seem to be subject to the same rules of engagement as the locals are.

This approach was applied by David Henley, for example, when he found evidence that the indigenous Minahasa on Indonesia found a certain usefulness in the 17th century Dutch East India Company, in particular because Stranger Kings tend to have “aloofness from local rivalries” and an “ability to provide relatively impartial conflict resolution”. The Dutch East India Company was unambiguously self-interested, colonial and extractive, but the point is that, rather than being mere meek bystanders to its history, local people had ambiguous entanglements with the corporate giant. They experience the coercive violence of the colonist, but may still take a gamble on a Stranger King.

King Donald the Strange

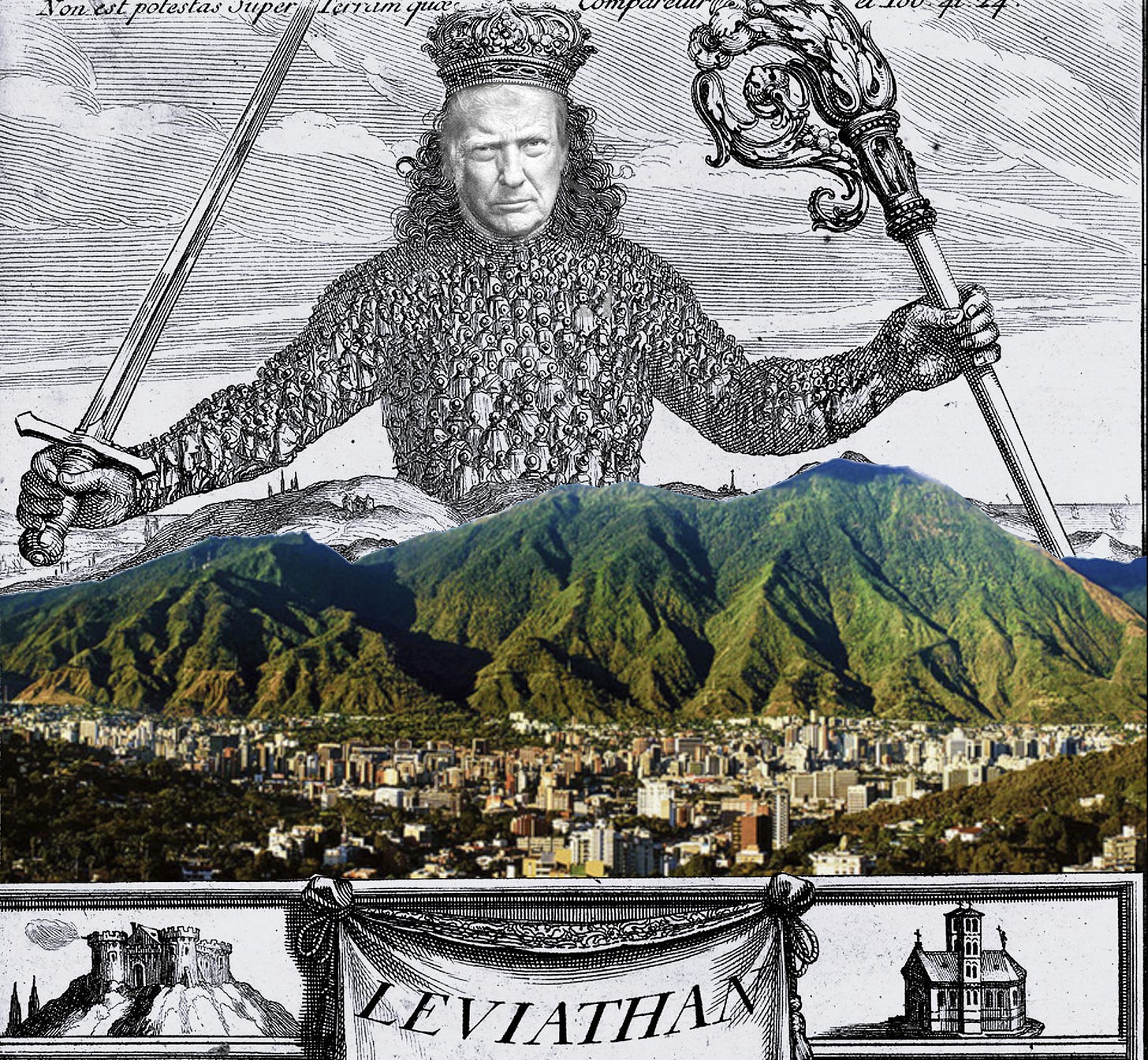

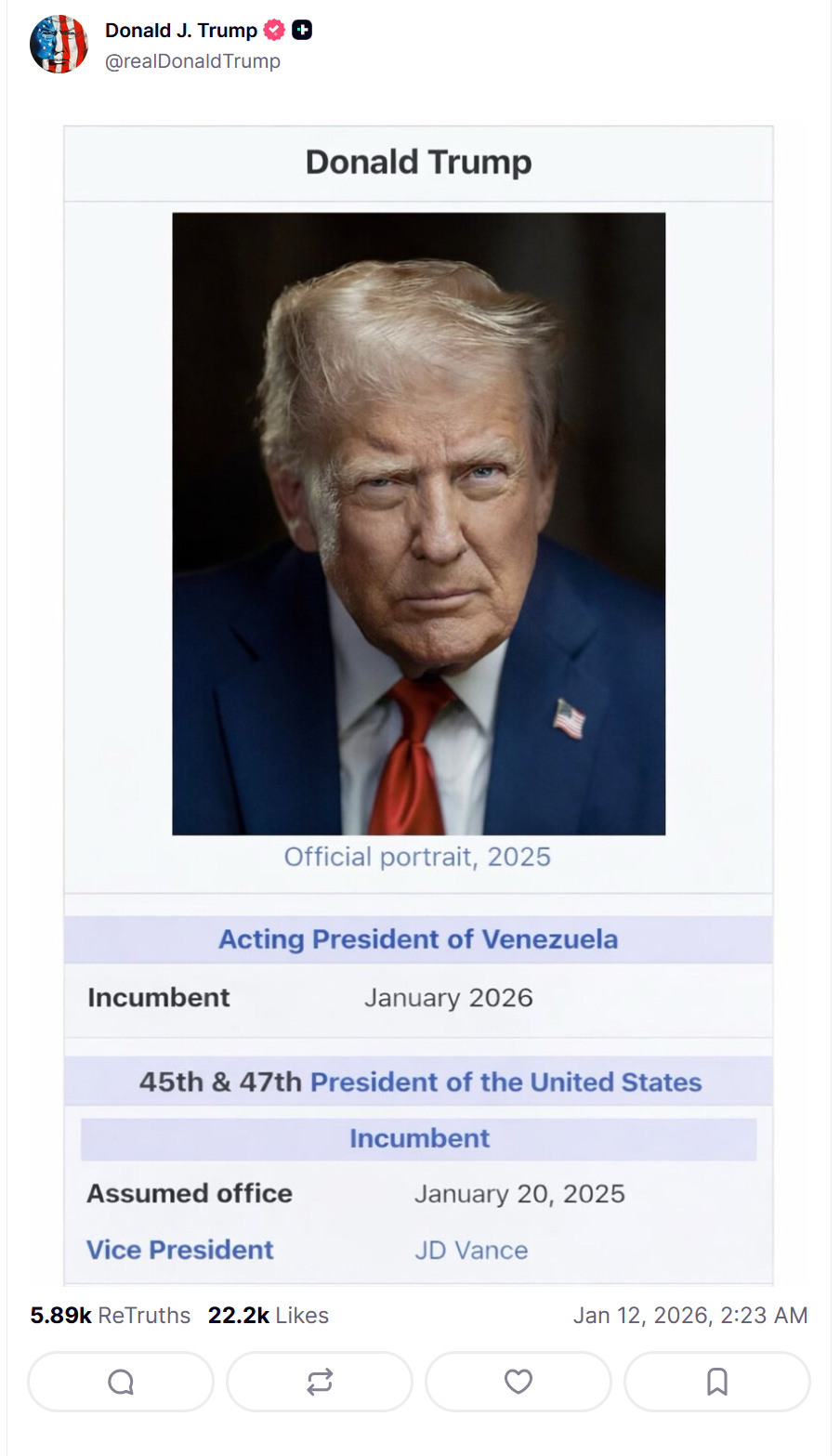

On January 12th 2026, Donald Trump posted a picture of himself on Truth Social, with the tag ‘acting president of Venezuela’. His takeover of the country is unambiguously colonial. Like all colonial ventures, however, there are many who will find ways to justify it.

For example, the conservative press has predictably fixated on the pre-existing dictator - the figure of Maduro - and his spectacular humiliation and overthrow at the hands of a cunning outsider brimming with almost supernatural vitality. There are stories about the jubilation of exiled Venezuelans, weeping with joy and thanking Trump.

Then we have all the stories about the blatant geopolitics of this. Unlike George W. Bush during the Iraq War, Trump has made almost no effort to disguise the fact that the regime change is all about THE OIL. In fact, he’s loudly proclaimed that it’s about the oil. He’s gone out of his way to talk about how US multinationals will literally take over the country. This makes it very easy for the left wing press to point out the very obvious imperial dynamics of this resource grab. Hell, even the centrist and conservative press are struggling to ignore that.

Let’s forget about the global press response, though. Through the eyes of many Venezuelans, we have here all the elements of a potential Stranger King situation. Ok, Trump isn’t a young, handsome challenger, but he certainly is a foreigner who doesn’t feel encumbered by traditional rules. In fact, the blatant impunity of his oil grab adds to the sense of awe and mystique around him, and he has certainly deposed a local despot.

At the risk of pushing the framework too far, we even find strange echoes of the mythological ‘marriage to the daughter’ element of the traditional Stranger King story: the female power players of Venezuela, like Delcy Rodríguez and Maria Corina Machado, must now domesticate the irascible outsider by entering into deals with him.

Crucially, while it’s true that the US actions have thrown the Venezuelan establishment into turmoil through violence, there already was turmoil in the pre-colonial situation, so this new incursion has simultaneously opened up new opportunities for local elites (and exiled elites), some of whom have long been seeking some way out of the situation. This could be a usurpation, rather than conquest, with potential for elites to strike a new ‘social contract’ with the foreign power.

Let’s take a moment, however, to unpack that loaded phrase, and how it relates to the Stranger King concept.

Social contract theory vs. social contract reality

The term ‘social contract’ is heavily associated with classic liberal theory, and classic liberal theory is a heavily abstract way of thinking about the world. When I say ‘liberal’ here, I don’t mean it in the modern US political sense, but rather in the original philosophical sense: early liberal philosophers - like Thomas Hobbes and John Locke - basically started from the assumption that humans are:

Individuals

Rational

Possessing of some kind of natural ‘individual rights’

From that opening position they then describe social formations as collections of individuals who have rationally come together. This sets the scene for mainstream economics, which basically says exactly the same thing, but applies it to economic interactions.

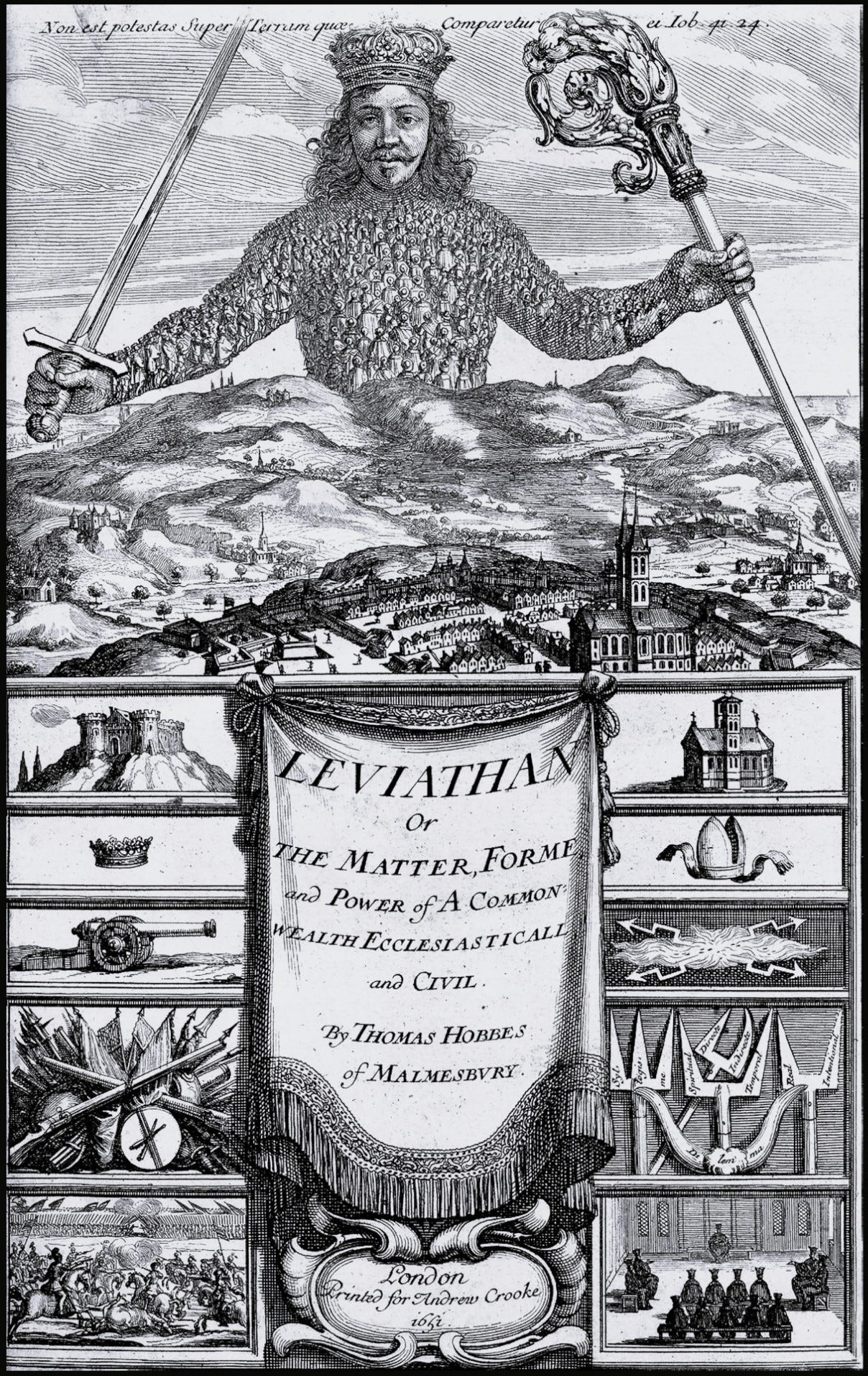

In the case of standard economists, they imagine individuals ‘choosing’ to ‘come together’ to ‘form markets’, but in the case of our 17th century Hobbes, he imagines rational individuals choosing to come together to form… well… a kind of absolutist monarchy to rule over them (which is partly why Hobbes is often misinterpreted as being ‘illiberal’).

In his Leviathan (1651) he explains that a monarch is a creation of individuals, who have chosen to give up part of their freewheeling-but-chaotic freedom (which they would have in a ‘state of nature’) in order to enter into a more constraining social contract with a monarch, in which the monarch will provide some structure - like property rights, law and order - so that the individuals can pursue their self-interest without being disrupted by disputes, theft, instability or in-fighting.

In it’s own context, Hobbes’ Leviathan was an attack on the idea that monarchs derive their power from a god (hence him being accused of atheism), but by describing kings as the secular creation of individuals, he also implied that individuals could dissolve the social contract if necessary, and return to being in a ‘state of nature’.

This was a politically radical statement to make in the context of 17th century England, but as a generalised account of actual human history it is kinda bullshit, precisely because - like all classic liberal theory - it starts from the ahistorical assumption that humans are individuals and that social formations are ‘chosen’. In reality, every person in history has always been born into an existing social context (aka. societal enmeshment always precedes any perception of being an individual, rather than the other way around) and it’s only in edge cases that we find a random collection of fully-grown adults who are somehow untethered and able to explicitly make some new ‘social contract’ with each other (for example, the only time I’ve ever experienced a ‘social contract’ was when I became naturalized as a British citizen, and - in the ceremony - was given a literal list of my rights and obligations, but of course no British-born person has ever seen this, and none of them ever ‘chose’ to ‘enter into’ the contract).

Still, the edge cases are important, and in many ways Stranger King myths describe one type of edge case. In a pre-existing society in a state of turmoil, it is possible for a foreign ruler to appear as a type of ‘Leviathan’ figure that can be ‘contracted’ with by allowing them to usurp. This might make some kind of rational sense to people entangled in an otherwise intractable conflict, who can dissolve some previous entanglement by jumping ship to the new one.

This is not to say that this will work out for the people involved, but this does help us to move past binary perspectives on the current Venezuela situation. On the one hand, I find Trump to be an obnoxious narcissist - and he’s now upping the stakes to being an unapologetic coloniser too - but I can still understand the gamble being taken by, for example, a Venezuelan exile who agrees to grant some leeway to him.

The Returning Stranger King

Let’s conclude by going one layer deeper. Perhaps the Stranger King myth is crucial to the entire Trump show, beyond his current Venezuelan adventures.

Think about it. In the run-up to his political campaigns, Trump has always presented himself as some kind of heroic outcast - a prodigal son in exile, shunned by The Establishment. The twist here is that he’s not technically a foreigner in the US, but he fashions himself as a local son that’s estranged from his true home, unfairly misrepresented by the New York Times, mocked by Hollywood, disrespected by Time Magazine.

From this starting point, the mythology unfolds. The estranged son returns as a Stranger King with a celestial mandate, on a mission to form a ‘contract with the people’ against the despotic ‘deep state’. This justifies overriding all pre-existing norms, checks and balances.

In Making Capitalism Bad Again, I noted that at least part of the euphoria that surrounds Trump comes from the fact that he gave permission to people to ignore the cognitive dissonance that characterises liberal versions of capitalism - the sense that you’re supposed to be a Good Boy and a Bad Boy at the same time - and, by taking on the ‘bad boy’ mantle, he indeed appeared as a monstrous outsider not subject to the niceties of the society.

In presenting himself as above and beyond existing norms, he could take on that Stranger King immunity. Through this lens, actions previously considered reprehensible - like attacking the press, centralizing power into the executive, threatening the judiciary, defunding the universities, sending in the National Guard to quell protests etc - can all be framed as signs that the Stranger King isn’t subject to the rules of the realm, and thereby draws his power from some distant, mystical source. That becomes a sign of his legitimacy in the eyes of his followers.

Returning the Sahlins, the Stranger King often comes to power not through conquest, but by usurpation aided and abetted by a local population who see in them a certain usefulness. There are many people who voted for Trump not because they particularly like him, but simply because they took a chance on him, seeing him as the proverbial Stranger, and ignoring his obvious inconsistencies, hypocrisies and flaws, while focusing on his outsider status, which gives him a quasi-supernatural vibe that may be worth taking a gamble on.

Given that Trump is heavily narcissistic, however, this Stranger King story probably plays out in his own head. He is now triumphant, yet remains deeply vulnerable, incredibly thin-skinned and increasingly maniacal. The Trump show might fly in 2024, but as time goes by, and as he gets increasingly lost in his own mythology about himself, he loses sight of those that brought him to power.

As he screws over the US shale gas industry by flooding the US with Venezuelan oil in an attempt to deal with inflation caused by tariffs, or sides with the Big Tech barons who couldn’t give a rat’s ass about the rust belt, or disses the CEO of Exxon Mobil, he makes more and more enemies of those who took that gamble on him. Everyone smiles deferentially at the Stranger King, but it’s entirely possible that they’re all waiting for that moment when a newer, younger, and more handsome stranger sets foot in the land.

Marshall Sahlins and David Graeber, On Kings (Hau Books, 2017) https://haubooks.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Sahlins-and-Graeber-On-Kings.pdf, Pg. 223

On Kings, Pg. 5

On Kings, Pg. 6

On Kings, Pg. 5

On Kings, Pg. 145

This pairs well with the idea of institutional immunity.

The Stranger King myth explains why transgression can confer legitimacy but only while the ruler is perceived as operating outside ordinary contestation.

Once the “stranger” is fully inside the system markets reacting, courts responding, institutions adapting, the mystique collapses into exposure.

Modern power doesn’t fall when legitimacy breaks; it persists under permanent visibility.

Thank you for putting this article together in your inimatable way.

It's notable how quickly the conversation moved away from ordinary Venezuelans and Venezuela as a nation.

While comparisons and wider implications are interesting, in an ideal world they should be balanced with the specific realities of each situation.

Venezuela used to be the wealthiest country in Latin America; now it is in the bottom 10–20 in the world. The Gini coefficient has always been extremely high (which is what propelled Chavismo), and that is still the case.

For example; If Colombia, Guyana, or an alliance of Latin American nations had made the same move, I feel the narrative would be quite different. However, for two decades, nobody did. Ordinary people suffered: medicines were and are scarce, liberties were and are restricted and survival from day to day became and still is the focus for many. You won't hear many Venezuelan voices, and that's for a good reason: fear. They know they must keep quiet. This is not over, and we all know that. However, the future of a whole nation is riding on the hope that this could potentially be a small step in the right direction.

This article probably covers it better than I can https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/venezuela-without-venezuelans-maduro-trump-media-coverage/