There is no Black Friday

And the overlords of the global village spam us with cultural malware

Paying subscribers can access the audio version here (17 minutes)

Quick note: my book Cloudmoney is now also out in Portuguese and Polish (woop!), taking the total number of languages to twelve. Message me if you’d like to be directed to a copy in your own language.

There are an estimated 1.5 billion computers that run Microsoft Windows, and each day a team at Microsoft gets to decide what topic they’ll push into the world’s consciousness via the search bar on the bottom of a Windows screen. Last week I got a parrot wearing a pirate hat.

It turns out that this parrot represents International Talk Like a Pirate Day.

Well, me maties, the question I be interested in is this: what percentage of ye knew of International Talk like a Pirate Day before this?

I’m interested, because over the last months I’ve become aware of two things about the Microsoft search bar. Firstly, it showcases topics that have zero connection to each other, and which fluctuate seemingly at random. Secondly, it projects these onto me and a couple billion other people.

This plays into my general morbid fascination at how arbitrary decisions made by a handful of people can get amplified, embedded into our culture and stuck there for good. For example, I’m struck by the fact that two billion people on WhatsApp have to look at the same colour scheme every day when messaging.

People of radically different political stripes send radically different messages on WhatsApp, and yet everyone is united in recognising this colour combo as a backdrop to their culture. In fact, it’s part of our culture, but none of us ever had any role in deciding upon it. The team at Meta could just flick a switch and change it. Sometimes they do. Their UX changes send shock waves around the world, as everyone scrambles to readjust their perceptions.

These top-down projections don’t only occur in digital space. As noted in my piece The War on Informality, I get weirded out by the fact that millions of people who take the shuttle between the south and north terminals of London’s Gatwick airport are subjected to the same dull advert for EasyJet packaged holidays for the last couple years. Much like a dog learns that certain areas of the house mean certain things, Londoners learn that the geographic space between the terminals is inseparable from that airline’s slogan.

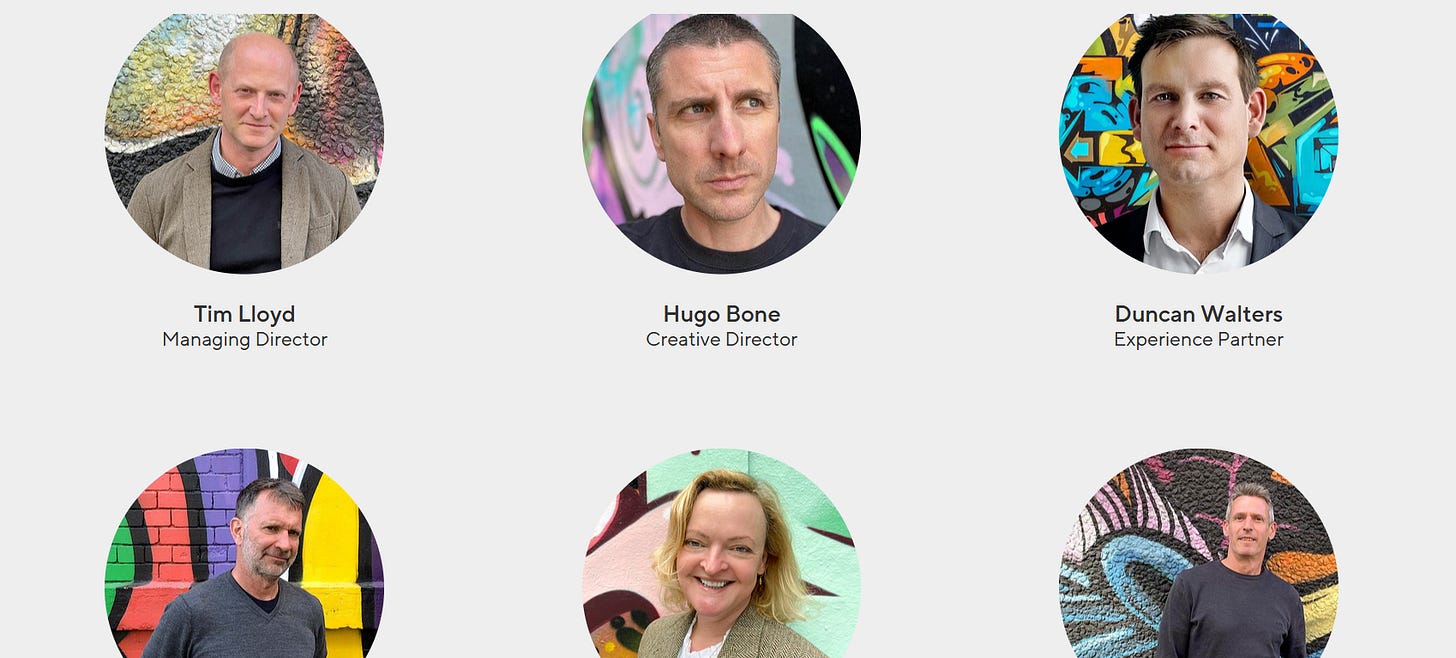

In fact, I sometimes try to put faces to the people who create these cultural artifacts. For example, in the image below, we find Tim, who - according to his bio - enjoys driving tractors, and Hugo, who likes watching Nordic noir, and Duncan, who is fond of wood-fire cooking.

Most Londoners don’t know these people, but they do know the incessant notification this team designed, because See It, Say It, Sorted is broadcast out of loudspeakers in London train stations ever ten minutes.

When I hear ‘See it, Say it, Sorted’, I picture the banality of the meetings that gave rise to this paranoid catchphrase, which is designed to get people to rat on each other. I picture Hugo talking to Tim about dropping his kids off at school while a nervous intern waits to take notes. I imagine the British Transport Police team giving them the contract, and how they maybe went out for dinner and cocktails afterwards, having laid out a phrase that literally millions of people will have to hear every day for the next, maybe, twenty years.

The world’s media fixates upon the Trump vs Harris presidential race because decisions made by the US leader can affect the lives of everyone globally. I think, though, that decisions made by corporate operatives make much more immediate impacts into the texture of our everyday life. There should be a Time Magazine profile about the person who composed the default text message sound on Samsung phones. There should be global debate about whether we like ‘spaceline’ or not. After all, we’re going to hear it regardless of whether we use the phone.

This is why I’m interested in International Talk Like a Pirate Day being projected into my world via Microsoft. How and why did this decision get made, and why do I have to deal with it? Why must I talk like a pirate now?

Global Village Life

I understand that most people don’t have this fascination. In fact, maybe you’re thinking, ‘hey chill Brett, it’s just a bit of light-hearted fun that we enjoy’, but here’s my issue. I’m increasingly convinced that there is no ‘we’. Rather, ‘we’ increasingly experience the world as isolated and alienated people who are mostly stuck in urban environments dominated by physical corporate and state interfaces (billboards, store-fronts, infrastructure etc) whilst also being stuck behind computers and smartphones dominated by Big Tech, which tries to feed us that illusion that the Internet is a ‘global village’.

‘Global village’ is now an old-school term, associated with the optimistic early years of cyberspace, because where’s the village now? In reality, it’s Amazon AWS, Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud Platform data centres, towering like digital skyscrapers from where the highest bidder gets to project themselves onto everyone.

Let’s talk about an actual village. Picture a group of people in rural Ireland slowly forming a tradition of harvest festivals during the 15th century, drawn together by some shared common context of being agrarian peasants. There’s a rootedness, or shall we say authenticity to a harvest festival. It has some chance of organically emerging without top-down pressure.

Similarly, the original global village of the Internet did give some scope for organic upwellings, the digital equivalent of peasant festivals. So, in 1995 some people did use the Internet to send out messages to get people to talk like a pirate on a particular day, and International Talk Like A Pirate Day was born.

But, me choosing to shout ‘ahoy there maties!’ upon receiving an email through an old nineties peer-to-peer mailing list is a fundamentally different act to me shouting it out last week at Microsoft’s instruction. The latter is like a feudal lord instructing villagers to turn up at a festival.

Ok, it’s not like top-down projection of culture hasn’t been happening in other forms for a long time. For example, the big record companies have a strong pedigree in manufacturing mass culture - like boy bands - and force-feeding it to us from above while presenting it as our own bottom-up desire. But, in the early days of the Internet, there really was a sense that we could skirt past these behemoths. The whole Napster generation had that feeling of a digital Robin Hood movement, peasant outlaws operating in the thick forests of the web. In fact, even when the platforms like Google started getting powerful in the early 2000s, they seemed to be, well, platforms that could serve as a substrate upon which an organic bottom-up culture could take root.

Over the last decade we’ve shed much of that vision, and ended up in a weird cognitive twilight zone. On the one hand, we’ve slid like slow-boiled frogs into a gradual acceptance that the tech platforms are now not only mandatory infrastructure for economic life, but are also top-down gatekeepers of culture, whose algorithms, feeds and interfaces becomes the mainline via which it gets propagated.

This has led to a lot of angst in recent years, but much of that has been focused on content moderation and censorship issues in the context of the ‘culture wars’. Conservatives are convinced that Big Tech forces everyone into ‘wokeism’, but it’s just as apparent that the platform algos will amplify all sorts of memetic viruses, from Bitcoin speculation to far-right radicalisation. Twitter was at the centre of this for some time. In its early years it felt healthy, like a heady and chaotic ‘global village square’ where people would get on soapboxes and shout stuff out, but that vibe shifted with the arrival of the algorithmically-weighted feeds, which began to place top-down pressure to make you see more of what you’d already seen, to inflame you, to get you hooked, and to keep you there.

We of course also saw the concurrent rise of the crypto-token movements, which ostensibly tried to reinvent the peer-to-peer Internet, but much of that has been captured by its own excesses, turned into bloated VC-funded parodies of rebellion or fantasy ‘network states’ funded by billionaires. In fact, former Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey used his platform to sell people on Bitcoin, as did Elon, who also claimed to be a liberation fighter when he bought Twitter to free the platform from nefarious censorship.

Rather than being a bastion of free speech, though, Elon’s X has degenerated into a private receptacle for him, like a village square with a giant screen rigged up to broadcast regular wisdom and sayings from Chairman Musk. How I’d love to discover which obedient X engineers were given the humiliating task of programming the lines of code that would insert their boss’s ego into everyone’s feed. Maybe they too like wood-fired cooking, or Scandanavian crime dramas.

With the crumbling of Twitter, there has also been a crumbling in the old belief in a single Internet. The fact that Elon will now spam the village square has led to people drifting off in different directions. That’s one reason why we’re here on Substack, because it’s one place enthusiastically taking in refugees (something I welcome).

But, this focus on whether our voice and content is being constrained, censored or amplified by X, Y or Z platform obscures the fact that in the background, the giants of tech infrastructure continue to make more subtle - and often more impactful - cultural decisions on our behalf regardless. For example, have you noticed how literally every single tech company has started shoving AI tools at you over the last several months, pushing them into your feeds or into the boxes on their interfaces? Have you found yourself building a gradual sense that everyone must be using it, and that this is what we do now? Have you noticed that in that time your perception of the twinkle emoji solidified into a symbol for that? That wasn’t us who decided upon this. It was the marketing departments of the platforms.

In fact, while it’s possible that X will die a slow death as people get bored of Elon’s cult of personality, operating systems like Windows are pretty damn entrenched. Elon only has 198 million followers on X, but an anonymous team at Microsoft can project anything they want onto ten times as many people, whether that be their Copilot AI tool, or International Talk Like a Pirate Day. In fact, for all we know, the search bar topic could be a running joke among employees. They could piss themselves with laughter as they say ‘let’s make a billion people say arggg today’.

The parrot icon on my screen was ostensibly there to describe something, but it equally functioned as a prescription that I should care. It was selected for me, and this top-downess makes a difference. It becomes like cultural puppetry, and yes, I do get irritated by being puppeted. But, if I briefly get off my high-horse, I suppose Talk like a Pirate day is relatively benign. Perhaps the 1995 founders are happy to see a techno-feudal overlord instructing everyone to take part. It gets worse, though, when the lords just invent new days for their own cynical purposes, like Black Friday and Cyber Monday.

Avast lubbers! Hear my Black Tale of Cyber Monday

The term ‘Black Friday’ originally referred to various disastrous days, including a financial crash in 1869. In the early 1950s, a couple academics used the term as a description to refer to the day after Thanksgiving, because people would feign illness to skip work and get a long weekend. Certain police departments in US cities also started using it at that time to refer to the beginning of the congested weekend at the start of the Christmas shopping period. In all these cases, the phrase was applied from the perspective of outside observers, in the way ecologists might have a term to describe the annual migration of gazelle.

In subsequent decades, though, the name ‘Black Friday’ was slowly hijacked by a narrow class of corporate marketers, who tried to get the gazelle to include it into their own self-identity. Rather than using it as an after-the-fact description of observed behaviour, it became a before-the-fact prescription, a call-to-action that you were supposed to go shopping. In our ecologist metaphor, the term ceased to be a description of herding behaviour, and morphed into an instruction to stampede the shops.

Many philosophers and mystics have long sensed that the act of naming can create reality (my favourite book about this is Ursula K. Le Guin’s Taoism-inspired masterpiece A Wizard of Earthsea), but the modern masters of this ‘speaking into existence’ are corporate marketing teams. By repeatedly naming Black Friday, it was turned from a passive phrase denoting some loose behaviour into an actively charged cultural object that could pull people in like a magnet. In the era of digital globalization, this object, which was built by the US capitalist class, exploded mimetically through the marketing departments of all the other corporations globally. It’s now locked into place in every country and will not be dislodged, unless we see the fall of capitalism or the heat death of the universe.

Black Friday is as much a top-down order to behave in a certain way, as it is a description of a real bottom-up cultural phenomenon. In this sense it shares some common ground with Christmas, which has also been co-opted as a symbol of, and instruction to, engage in mass consumerism. Christmas, however, still holds onto some shreds of an actual religious holiday that once did exist, while Black Friday is like Christmas stripped of any illusion of cultural depth. It’s foisted at us every year, like the clickings of a corrupt ecologist who needs to remind the herd to make that migration.

When encountering all the top-down Black Friday ads, I’m always reminded of Louis Althusser’s concept of interpellation. It refers to the method of programming ideas into people’s minds by addressing them as if they already agree with what you’re saying. To understand this, let’s look at one of the purest examples of this phenomenon: Black Friday’s sister festival, Cyber Monday.

Cyber Monday was written into existence by a press release from the National Retail Federation (the biggest retail trade association in the world), which said: ‘Cyber Monday Quickly Becoming One of the Biggest Online Shopping Days of the Year’.

All the subsequent commercial slogans, like ‘Cyber Monday is Here’, and ‘Are you ready for Cyber Monday?’, speak at you as if you’re already a person who agrees this thing is a reality. This generates a feeling of a movement, of a whole mass of people somewhere - presumably - who already know about this thing that you’re only catching onto now.

Of course, nobody has ever seen anyone else celebrate Cyber Monday, because in reality it has no organic existence. Like the current version of Black Friday, it was genetically reverse-engineered by companies that spoke of it as if it were a reality.

This power to speak-into-existence has escalated as our economic survival has become tied to an Internet controlled by a small number of players. Let’s face it. There aren’t that many on-ramps into the ‘global village’. Rather, there are a handful of operating systems, the makers of which also own the gigantic search engines. They, and a few others, collectively form a meta-interface that gets to tint and filter the world we see, to foreground things, and push others back, often guided by nothing more than the profit motive.

As I discuss in The Three-Faced Interface, these top-down interfaces increasingly give themselves first-person pronouns, and cloak themselves in your own image, appearing as your, well, co-pilot to life.

Before people say I’m being doomerist, I’m not saying that we don’t still have any organic, bottom-up culture anymore, or that platforms are unable to do anything good. We do, however, need to be vigilant about these incursions from above. We need to consider whether AI hype, Cyber Monday and any other supposedly ‘bottom-up’ upwelling might in fact just be pieces of cultural malware downloaded into our minds from the curators of a holographic mock-up of a global village. We visit, and find this spam projected into us - the stories that are supposedly important, the mood, the next new thing. Today ‘we’ all celebrate Talk Like a Pirate Day, but what will we be instructed to care about tomorrow?

Well, it’s tomorrow now, and the curators have decided that today I must care about - wait for it - edible flowers. I do happen to care about edible flowers, and I applaud my M’lord’s decision to remind me of this.

I enjoy your work immensely. This is the kind of perspective I have been looking for with attempting to understand the economic and technological state of the world. Government and corporations have become the same entity and it is the techno feudalism of our times

Once again you have completed the processing of half-digested thoughts I’ve often had - “Black Friday? I thought that was a day of financial collapse (there’s an irony!). When did that become a thing?” Followed by a period of grumpiness and determination not to engage.

You bring a wonderful affirmation of my instincts and a clear explanation of these digital intrusions that restores my sense of being in touch with reality. Thanks, Brett!