Paying subscribers can access the audio version here

Economists frequently use blood metaphors for money, seeing it as a substance of value that ‘flows’ around the economy. Financiers love this vision of money as a circulatory system, because it creates an image of their sector as the ‘beating heart’ of the global economy.

Under this metaphor, money carries a payload, as if it were plasma transporting nutrients to cells. It’s seen as a delivery system for value. This belief is reinforced by those who characterize it as a ‘store of value’, as if value resides ‘in’ the money. Many people in the finance and fintech sector talk about payments platforms as ‘value transfer systems’, as if PayPal, Stripe and the banking sector provided pathways for the ‘store of value’ to carry its payload from point A to point B.

These liquid value metaphors are deeply misleading, and obscure the true nature of finance. Money isn’t like blood pumping through veins. It’s like nerve impulses jolting muscles into movement. To delve deeper, let’s start by looking at the ‘body’ this nervous system is embedded into.

The economy as superorganism

The average person has around 30 trillion cells in their body, but while each cell might appear as a single thing, they cannot exist separately from each other. If you remove a cell from your body, it dies. Cells, then, are an interdependent mesh that are collaborating, and you are the outcome of that collaboration. There is, as it were, an inner economy in your body, where cells collectively provision themselves, but take on separate parts of that overall process. If your cells had to discuss ‘the economy’, they’d be discussing you.

Some cells might be subsumed within organs, like your lungs and heart, which can also be seen as collaborating with each other. Picture your lungs telling your heart that before it can oxygenate the blood required by the heart’s tissues, it needs energy delivered to its tissues via a pump of the heart. This is the logic of interdependence: each organ might have its own internal processes, but you cannot expect them to survive independently of the other.

Human society is like this too. Like cells, we’re always born into a pre-existing social support network, and if we aren’t, we die. You develop an independent sense-of-self and personality as you grow up, but that doesn’t mean you can survive without others. In many ways we are the ‘cells’ of a social superorganism, and the economy is all those processes whereby we collaborate to provision for ourselves. Sometimes that collaboration doesn’t look or feel like collaboration. For example, the breakfast cereal you eat might depend on people on the other side of the world you cannot see, and yet without them there is no breakfast.

Needless to say, there have been many different styles and sizes of economic ‘superorganisms’ over time. For example, an ancient hunter-gatherer band sharing food around a fire might be visualized like this:

This is a small superorganism, but this was pretty standard for over 200,000 years. Like all groups, hunter-gatherers survived because sunlight and raindrops birthed plants from soil, which gave life to countless creatures, all arranged in ecosystems that kept them alive as they raised children, built communities and produced stuff. In those times, it was clearly understood that ‘value transfer’ meant a human being handing an actual good or labour across to another human being.

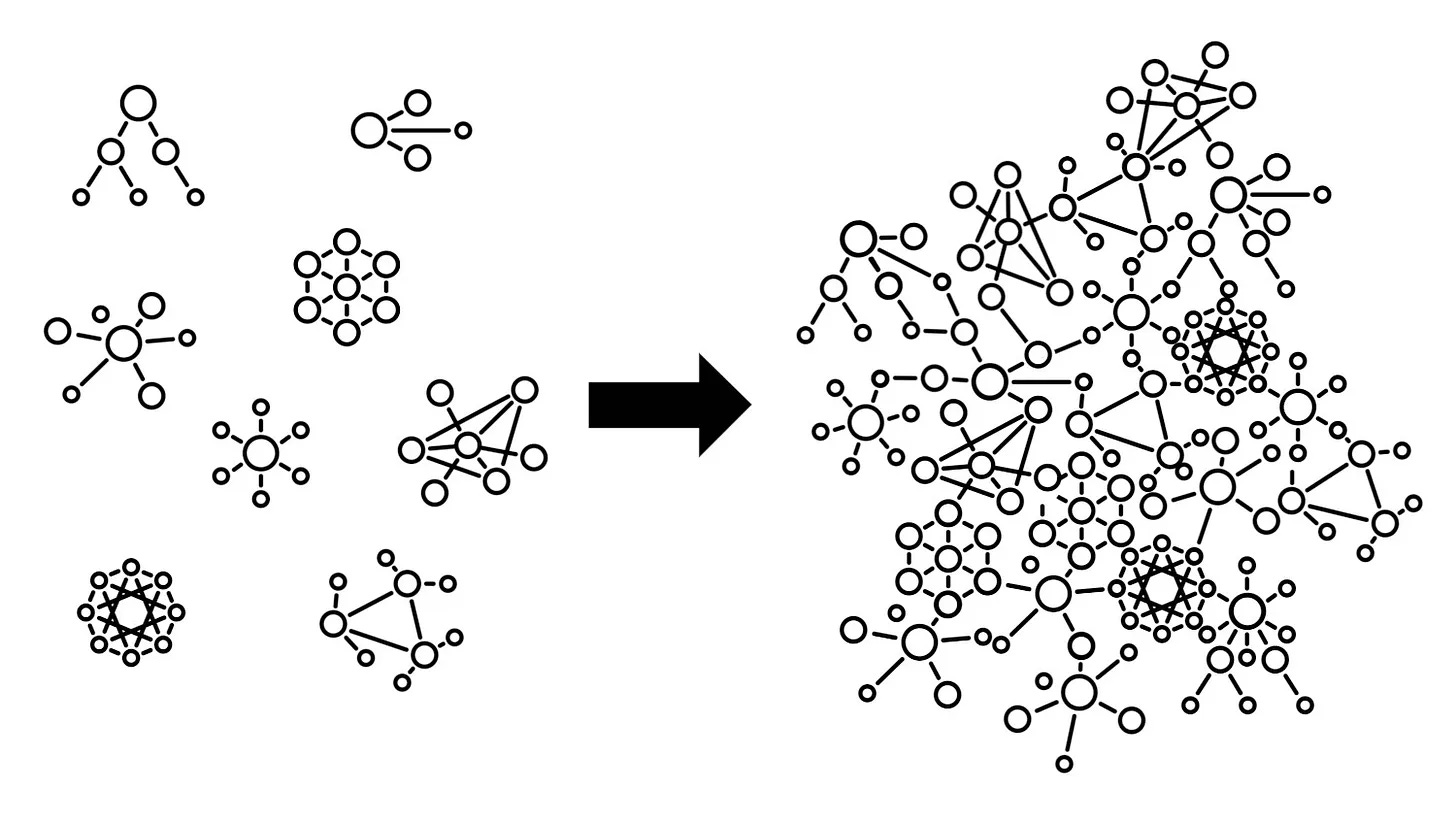

It’s only in the last 6000 or so years that money systems emerged. If I was to give a high-level potted history of money, I’d say money is a politicized system of credit that dissolved our previously small-scale systems of interdependence and recombined them into the large-scale systems of interdependence we use now (where we depend on people on the other side of the planet to give us cereal). We might visualize that shift like this.

The larger scale of a monetary economy also gives more scope for specialized clusters. Much like you can imagine cells clustering into interdependent organs that collaborate, you can imagine groups of people collaborating with other groups. For example, a small cooperative farm might actually have an internal structure that resembles an old hunter-gatherer band, but nowadays is but one sub-system of interdependence within a much larger system. The farm might rely on inputs from corporations, which are different sub-systems made up of different people.

The shifting superorganism

An ancient hunter-gatherer band operates on a different scale to a market economy, and has different power relations, but ripping a person out of either is like ripping a cell out of a body. A hunter-gatherer will find it very hard to survive solely by themselves, much like a person under modern capitalism will find it incredibly difficult to survive unless they can get provisions from everyone else.

These different structures of interdependence share a common feature: every person within them is caught in webs of inputs - those they rely on - and outputs - those who rely on them. The core difference between a hunter-gatherer economy and ours is that, in the former, the webs of inputs and outputs are small, tight, visible and relatively fixed. A person can literally see who they rely upon, and the structures of reliance stay pretty constant.

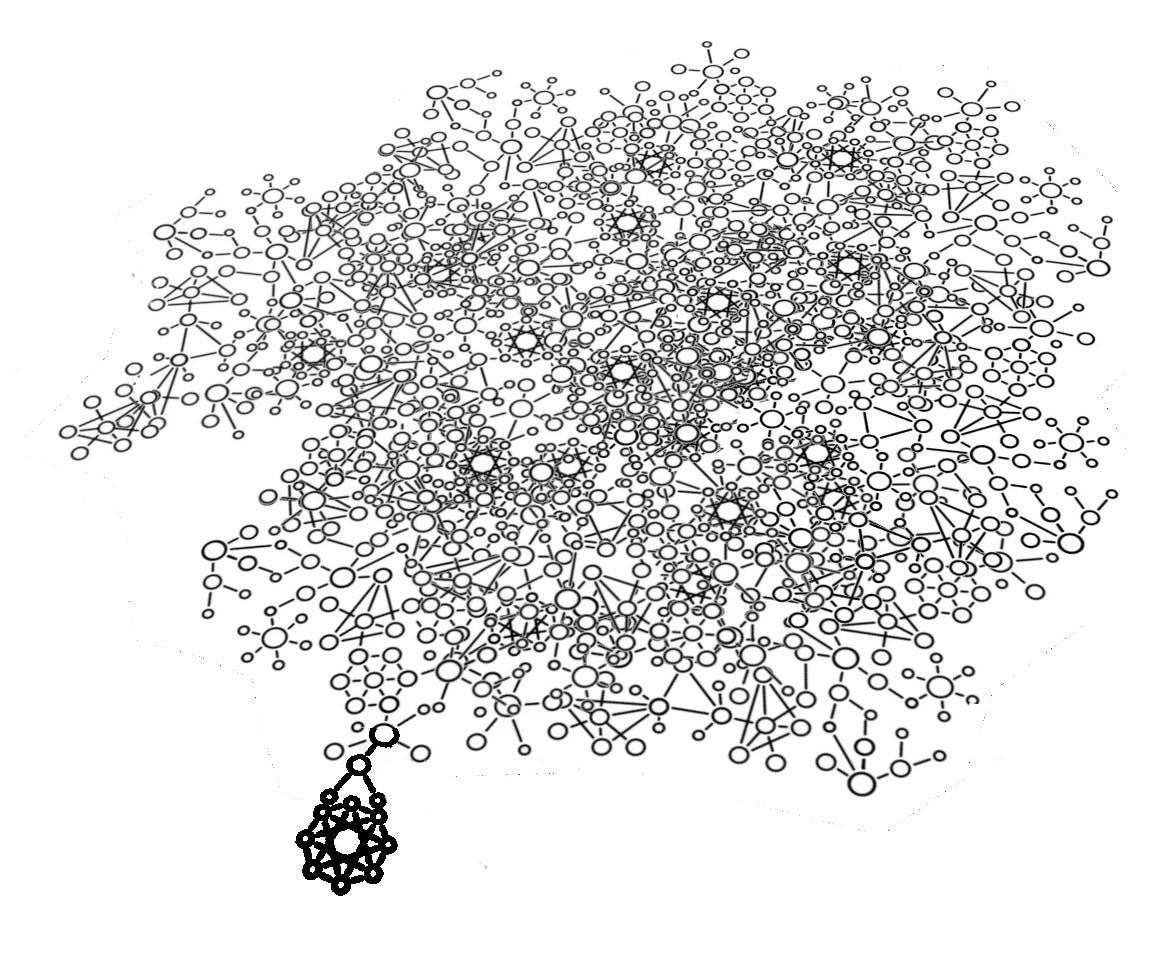

The webs of inputs and outputs in a monetary economy, by contrast, are far larger, looser, less visible and less fixed. This is because money is a system of credit that binds us together at scale, but the bonds can be fairly easily broken and recombined. Value still resides in people and the earth, but value transfer - by which I mean movements of goods or labour - is triggered by shifts in that credit. This is what gives our economy its fluid feeling. It’s somewhat like a system whereby cells (or groups of cells) can temporarily detach themselves from one part of the economic superorganism to graft in somewhere else.

That’s what’s happening when someone from our aforementioned farm decides to switch suppliers, and get fertilizer from a small family-run store rather than a big retailer. They are detaching from a previous input, and docking back in somewhere else.

In the case above, the cooperative farm is changing inputs, but their outputs can also change: for example, if one of their previous customers decides to switch to a supermarket to get potatoes. In fact, to visualize a market economy you’d have to imagine all the various parts in the image above constantly recombining into new chains of interdependence, like a superorganism that’s always rearranging its cell structure. Here’s a simplified visualization…

This system of fluid interdependence works by people, and companies of people, docking into inputs by redirecting credits. As I hand over money to my barber, I’m grafting into him, but I’m also mobilizing him into producing and outputting value. Notice that the value doesn’t reside in the money. It resides in the service my barber is giving me. If me and my barber were transported to a world without money, the potential value would still remain - there he is, standing ready to cut my hair. In our world, though, he won’t activate that value unless the monetary credit passes to him.

This is where the nerve impulse metaphor starts to kick in. When we zoom out we can view money like an interconnected system of impulses crackling through the tissues of an ever-shifting superorganism, resulting in movements and pulsations. Incidentally, this is also why market economies are so full of anxiety. To ‘dock’ into your inputs, you need money credits, but if nobody is docking into you (aka. you’re unemployed), you can be cut out of the structures of interdependence very easily, like a cell cut adrift.

Our interconnected networks are hard to see, but they spread to the furthest reaches of the planet, to the tiniest town. Often the shifts in this system are micro-movements, but there’s a particular part of our system that’s able to generate bigger jolts to mobilize bigger flexes. This is the finance sector.

Big Finance as the central nervous system

Much like our own nervous system concentrates in places like the spinal cord and brain (which has the highest level of neural density), our system of money concentrates in the world of high finance. Big Finance plays a major role in pushing money into circulation, pulling it out, redirecting it at scale, and also controlling the entire digital payments infrastructure.

This central nervous system includes the actual issuers of money - which bifurcates into central banks and commercial banks - but there’s also all the players like investment banks and hedge funds who design and trade contracts that scale up, steer, and complexify monetary movements, often via corporate structures.

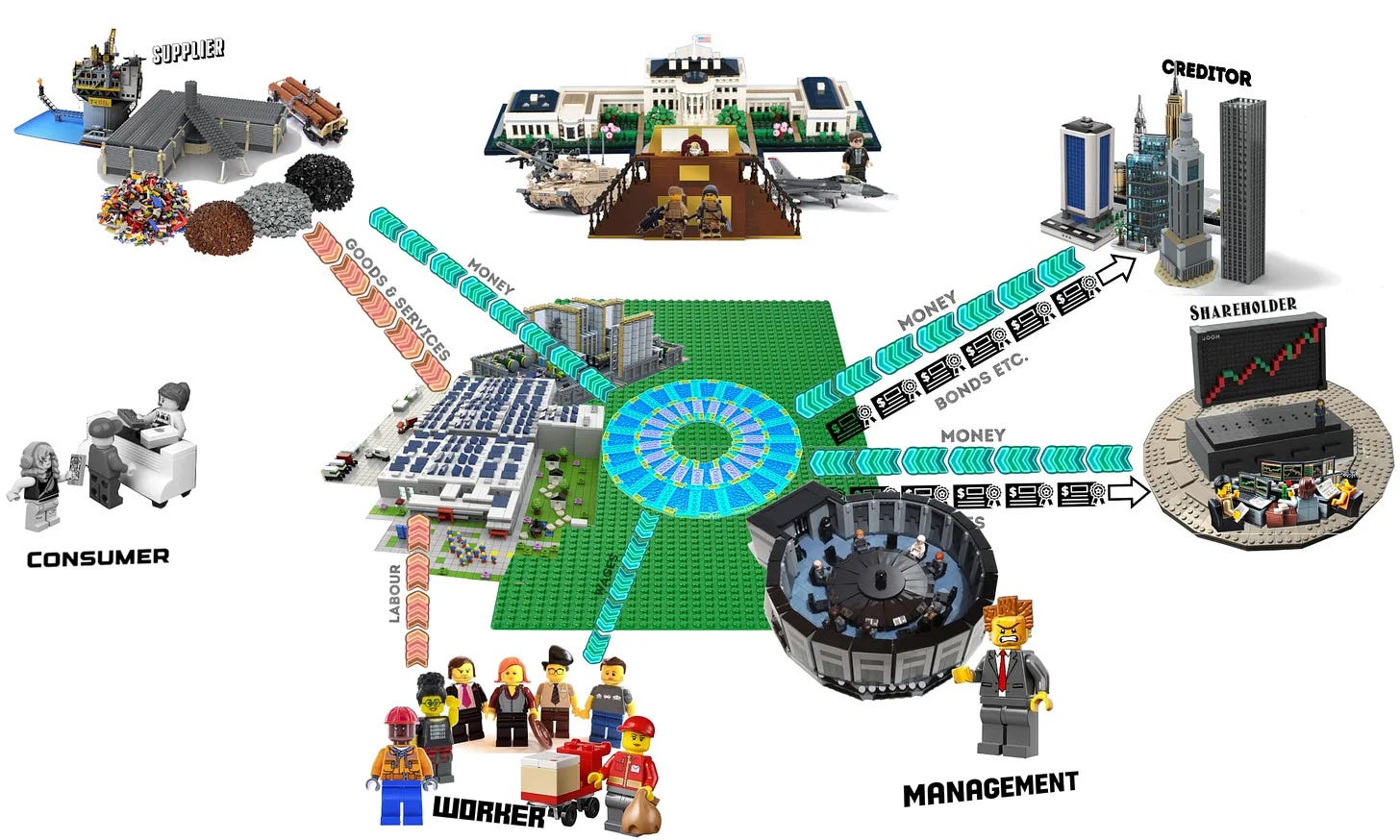

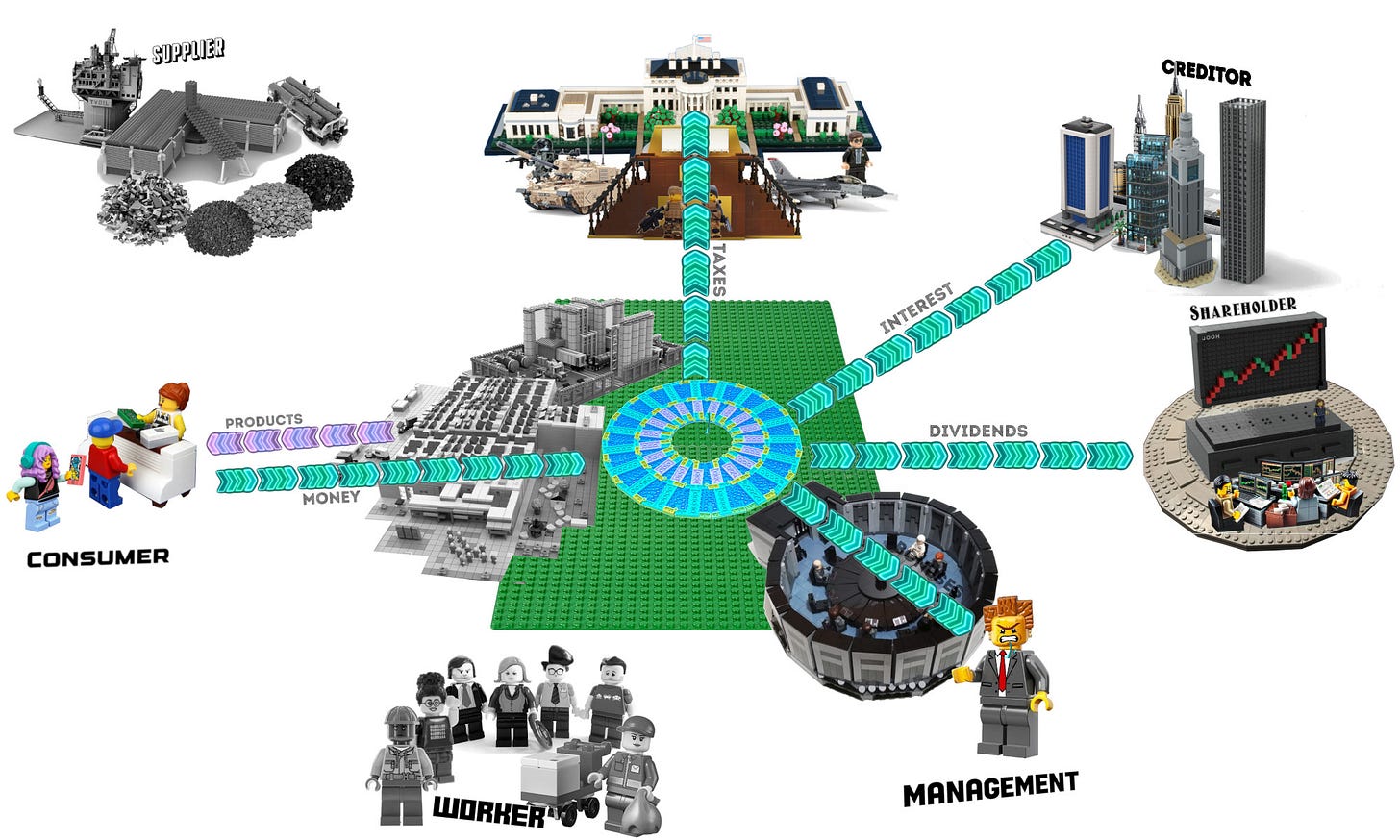

Our brain has a motor cortex that translates our thoughts into action, sending impulses that make our limbs move. Similarly, financial centres like London, Tokyo, New York, Shanghai, Singapore, Frankfurt, and Dubai collectively create a transnational ‘motor cortex’ that has the capacity to induce mass action in the interconnected body of workers that form the global economy. For example, a pension fund corrals together money from thousands of individuals into a huge ‘battery’ of monetary impulses, which they can release to charge up corporations seeking financing. This is what I cover in my Lego Corporate Capitalism series. Imagine them as one of the shareholders in this image…

In my 2022 book Cloudmoney, I summarise this as follows

The true lifeblood of an economy is not money but people carrying out labour. But a heart can be made to beat through an electrical shock. Once a corporation is charged up through capitalisation, it can blast that charge out through the monetary nervous system like a defibrillator kickstarting thousands of human bodies into large-scale action. This is how ten thousand labourers can be mobilised to make and assemble the components of an oil rig, and then operate it to extract the oil which their bosses can sell to customers… As the product is sold, it sends a flash of money back up the circuit. Some of that money exits in the form of bonuses to management and tax to government, while the rest gets sent to recharge the batteries by giving investors the future money promised in their financial contracts. In this way interest payments accrue to creditors, while dividend payments accrue to shareholders.

Ok, I slightly mixed metaphors here. I’m using imagery of batteries pushing out electrical charge through a nervous system, but this ‘money as charged impulse’ approach is far more accurate than a ‘money as blood’ one.

It also helps us understand various monetary phenomena like inflation, which refers to a loss of mobilizing power in the impulses. If you were to send nerve impulses into an exhausted muscle that doesn’t have the nutrients to move, the impulses lose their power (or purchase) on the muscle. Similarly, sending money into a situation where people and resources have hit a limit doesn’t mobilise action. The impulses fall flat, a process that ends up with shifts in the price level. By contrast, a group of unemployed young people standing in front of an un-farmed field is like a muscle bursting with energy but lacking directives from nerve impulses. They can be mobilized into action, and value-creation, through the issuance of new money.

So, the true ‘store of value’ in our society is human beings, everything we’ve created, and everything we can create within ecological systems. The true scarcity is never monetary impulses. It’s these real resources that reside in our bodies and the earth.

Numbness

Big Finance might operate like a motor cortex, but the financial crisis of 2008 made it very apparent just how deranged this motor cortex can sometimes be. Hundreds of thousands of workers were mobilized into constructing real estate that would stand empty, while precarious people were pushed into debt to buy it. Their desperate promises to pay back were bundled into packages and sold to mega-funds across the world. The financial sector was orchestrating a tragic dance, turning the global economy into something akin to a veering drunk losing their motor functions.

But, even when we’re not in crisis, the general direction of travel in our economy is like a dazed drift towards a cliff. We use up our planet’s resources in a short-termist drive for expansion while inequality deepens and power centralizes. I call this newsletter Altered States of Monetary Consciousness because if money is the nervous system of the global economy, it contributes to an emergent ‘consciousness’ in our superorganism that’s often both delusional and disassociated, and a core aspect of this is numbness: an inability to register or act upon pain.

For example, when you look at something bad in our economy - such as the mass dumping of plastics into our oceans - you face a question as to where that badness emerges from. Activists might imagine that the source is the corporate sector, with its corrupt or callous executives. From another angle, however, corporations are just conduits for the financial sector. After all, most corporations are owned by large investment managers like BlackRock and Fidelity that are acting on behalf of players like pension funds and insurance funds. Those players, however, will always claim they’re acting on behalf of their beneficiaries, which may be you or me. Put simply, the financial sector claims to exploit the world on behalf of us, making us the source of the problems we revile, but none of us perceives that we have the agency to change that.

The first thing to come to terms with is the fact that the monetary nervous system might bind us together, but it also scales everything, loosens our direct connections to the outcomes of our actions, and reduces our relationships to each other (and to our ecologies) to numerical ratios. When a monetary economy is your primary means of survival, it becomes as if you’re tied into a nervous system that’s dulled out its pain receptors and can only ‘feel’ one type of thing - profit. When we’re plugged into a systemic entity that cannot sense anything except monetary gain, it steers us in a very particular direction.

Some people claim that this state of disassociation - in which we’re guided solely by monetary incentives - leads us to utopia, while others claim it leads us to destruction. Either way, the fund managers and corporates will say they have no choice: if they don’t act towards maximizing monetary profit, they’ll be outcompeted and destroyed by the market. So, if you ever hang out in mainstream finance circles, you’ll notice that most analysts suffer from a bad case of ‘capitalist realism’. This is a term, coined by the late Mark Fisher, that refers to the state of mind in which it’s literally inconceivable to imagine any mode of action that doesn’t involve optimizing for profit and growth.

This means, when faced with the myriad problems of the planet, most mainstream analysts will never allow their minds to consider a deep level recoding of our system. Rather, they’ll default to some altered variant of their existing principles. They’ll imagine that ecological degradation can be resolved with ‘sustainable growth’, and that inequality can be solved by ‘inclusive growth’. In essence, they tacitly acknowledge that we live in a system that’s numb to anything except profit, so rather than expecting our system to feel ‘pain’ at the pollution of the oceans, a sustainable growth proponent will seek to make it pleasurably profitable for our system to create a solution. Make it profitable to protect the oceans, or to fight climate change, or to combat inequality.

To people like me, that looks a helluva lot like a shallow form of wishful thinking. It might lead us to the question of whether altering the monetary system - and it’s core institutions - might be a good vector for changing society (a question I touch on here), but a more immediate problem is that the agents of corporate capitalism are trying to centralize the monetary nervous system even further. You see, Big Finance controls the digital payments infrastructure, but this coexists alongside a peripheral nervous system that detaches from the central one. It’s called physical cash.

Cash is one component of our monetary system, and it’s locked into the same vast structures of interdependence as all money is, but its movement requires no corporate intermediation. It has a kind of peer-to-peer human ‘conductivity’ to it, with the impulse passing from hand-to-hand. In the current phase of global capitalism, cash has a relative skew towards localization and decentralization, but this clashes with the inbuilt default tendency of our system to seek out and destroy ‘friction’ in its relentless and never-ending desire to scale and burst outwards into new territories. Cash jams the corporate-underpinned drive towards large-scale automation, which is why it increasingly gets culturally demonized.

Amazon.com will not allow you to mobilize its warehouse workers, or its new supermarket workers, with coins. No, you must route the impulses through a centralized conglomeration of data centres run by the likes of Mastercard and the banking sector. When you zoom out, Big Tech and Big Finance are becoming like two hemispheres of a global mind, fusing through their natural synergies. I don’t know about you, but I sense it’s not the kind of mind we need for our global body.

Paid subscriptions to ASOMOCO give you premium access to special content, courses and audio versions. They’re available for the cost of a New York bagel or a London Tube ride. Think of it as treating yourself to a cup of intellectual coffee

"Big Finance might operate like a motor cortex, but the financial crisis of 2008 made it very apparent just how deranged this motor cortex can sometimes be. Hundreds of thousands of workers were mobilized into constructing real estate that would stand empty, while precarious people were pushed into debt to buy it. Their desperate promises to pay back were bundled into packages and sold to mega-funds across the world. The financial sector was orchestrating a tragic dance, turning the global economy into something akin to a veering drunk losing their motor functions"

And yet, the houses were built. Which means we had the resources to build them, and once built, it was a 'sunk cost' (in resources terms). And, there clearly was a demand for the housing as they were occupied, with families and lawns and real neigbourhoods of people enjoying life. And then interest rates rose, and loans became unaffordable, and people walked away, and the homes deteriorated, and the lawns became overgrown with weeds and the neighbourhoods became deserted and the property values fell even more, and then they were sold to some rich dudes for a bargain, wth the government stepping in to keep the banks afloat, while the vacant properties continued to decay, or were rented in some cases to the same people who once owned them and still needed a place to live. Instead of forcing sales, the Government should have guranteed banks on conditions that the banks write down their loan repayments to a level where the borrowers could continue to afford the repayments. Then people would have remained housed, the lawns mowed and the neighbourhoods vibrant. And in time, property values would have recovered. The 'loss' was only 'money'... and the Government has no lack of money... as QE proved

Thanks Brett, extremely... stimulating...!

It reminded me of these images https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/the-many-lives-of-the-medieval-wound-man/ thinking also of giants, and us as part of some sort of mega power ranger ;)

The nervous system works in (at least) 2 ways: as well as sending impulses for action, it also receives sense information. This relates to the numbness you talk about, and thus the question: how do we restore response-ability?

For me there is a lot in ideas of decentralised (and deeply interdependent) intelligence and selfhood that we as humans can express, contrary to the individualised separated cell-hood encouraged by our culture. The identities we have been taught to assume are defensive and disempowering postures which deny connection and are founded on blind (or numb) spots. As developed in the ecological and mycelium thinking of such as Sophie Strand, and this essay: https://hmirra.medium.com/holotropism-1cdf99c00b74 (I'd be interested to hear how this lands for those who don't particularly feel 'autistic' - my sense is it has something of the universal about it)

And questions of how I, as some sort of individual conscious focal point, node, or perhaps 'cell' interdependent with infinite and infinitesimal connections, part of organisms at many scales greater and smaller, can best act to increase health.

Awareness of the systemic wholes feels necessary to make visible the hidden patterns of connection and energy flow which have kept me limited and disempowered. The more I can see the ecology of my impact and interconnections, the more I can take responsibility for them - and the more attention I can bring to the health of my immediate surroundings.

I guess I'm feeling my way to the fine balance and interdependence between the big picture, and the hyperlocal. Health seems to be a good flow and rhythm of both...