The Outsider's Guide to Payments Censorship

Digital payments can be used to turn people off. But when do you care?

Paid supporters can access the audio edition here

Imagine having your smartphone removed from you for a week. You’d initially experience withdrawal symptoms, but your brain would quickly begin to recalibrate. You’d start to notice things in your environment you’d forgotten, like your ability to navigate through space by reading physical features, rather than relying on Maps. You might even find yourself feeling a little liberated, like a creature released from a zoo, relearning what it means to be a wild animal.

Now imagine you had all ability to pay for things removed for a week. This is a lot more serious than having your phone removed. Having your incoming or outgoing payments stopped in a market economy is economic suffocation. You’d be forced into dependence on friends and family, and if they’re not around you’d have to ask strangers for help. By the end of the week you might have become like an urban fox, scavenging through bins. Foxes do have a kind of freedom living in the shadows of our economy, but it’s not the kind of liberation that most people are looking for.

There are many established ways to censor the actions and thoughts of people, from media censorship through to intimidation. In a world where we’re dependent on money, however, the deliberate blocking or limiting of payments by authorities is a particularly devastating method. Physical cash historically provided a partial buffer against this, but as our dependence on digital finance gets entrenched, fear of payments censorship is rising. I’d like to dive into this as a case study, but to understand the politics we need to start with a more primal form of censorship found within our social structures.

Insiderness, outsiderness and censorship

No person survives alone. Rather, we survive in interdependent social clusters. Those operate with shared cultural rules and expectations that govern what is considered normal. People who fail to follow these conventions are often ostracised, blocked, or shunned. This version of censorship needs no police, and no surveillance equipment. It’s done by ordinary people, all the time. Kids learn early on that if they don’t want to be called a weirdo, they’d better conform.

I’m sure many readers have experienced forms of social ostracisation. Perhaps you didn’t abide by a gender stereotype, or show the correct set of interests. Perhaps you had some physical feature, like bigger-than-average ears, that marked you out as different. Maybe you failed to show enough enthusiasm towards the intended path for one born into your position.

I’ve certainly experienced this. The 1980s South Africa I was born into was violent and authoritarian. The white minority that I’m part of imagined itself as an embattled tribe under siege, and used this to justify a police state that suppressed the black population, banned books, controlled the media and limited movement. As a child in this repressive atmosphere, I sensed I was not fully welcome to express who I was, so I detached and built imaginary worlds. I wanted to draw pictures rather than kill rabbits with rifles. I failed to learn the names of the men on the national rugby team. I struggled to understand things that seemed obvious to my peers. I refused to follow music, clothing and technology trends, and began to take contrarian stands in the face of humiliation, but I could literally feel the surrounding social atmosphere trying to push the mute button on my voice.

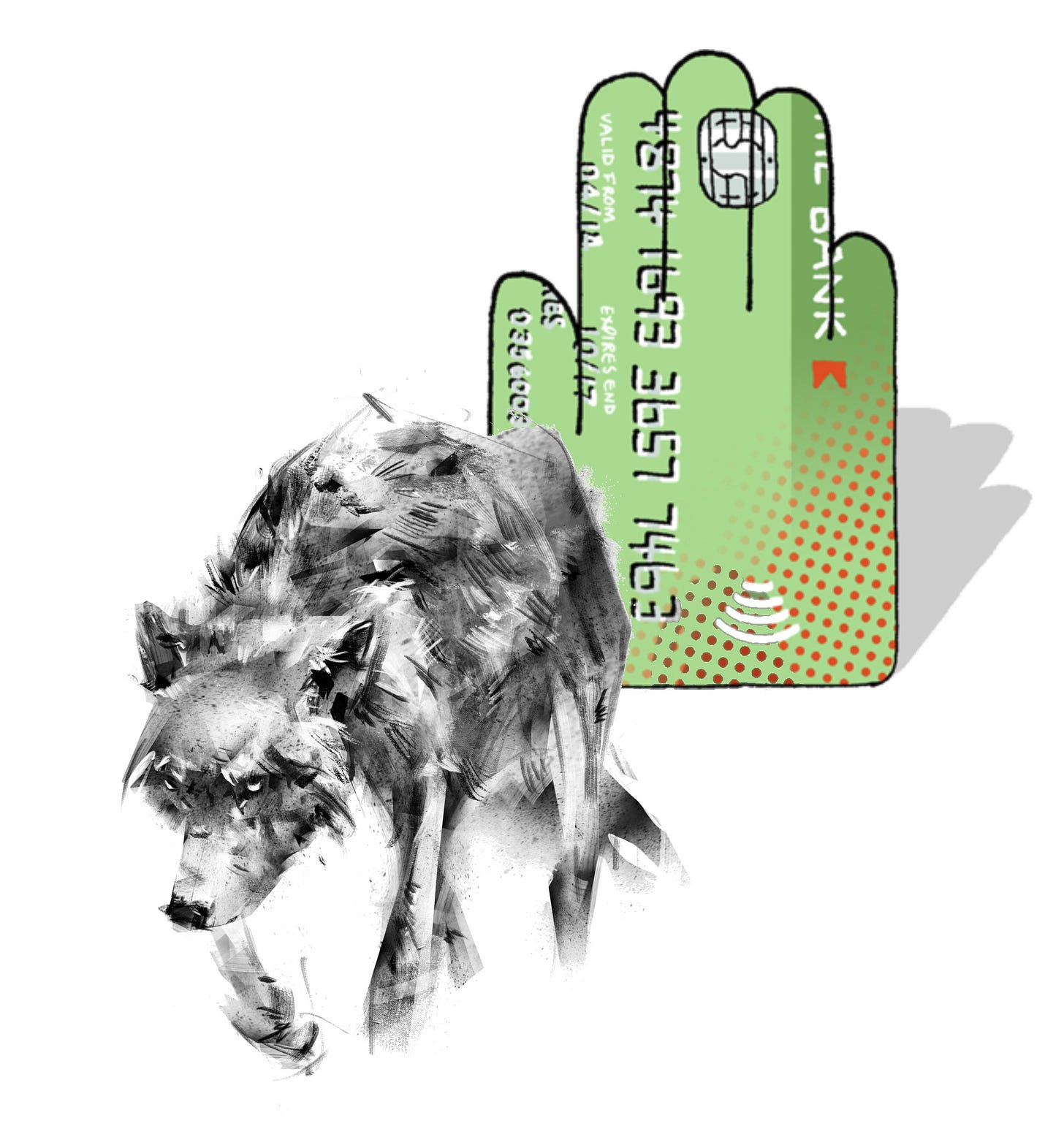

This is the outsider experience. The outsider struggles with trust, struggles to feel included, struggles to adopt the conventions that hold the normal group together, and feels precarious. Outsiders have an intuitive feeling for censorship - the blocking of voice and action - because we often get ignored, spoken over, mocked, and pushed to the sidelines. We have to deal with bullies who derive their identities by putting us down, and the subtler cruelty of those who simply turn their backs.

This sense of separateness and alone-ness is painful, but we also have the ability to turn that into a source of strength. An outsider can take their feelings of rejection and reflect it back at groups by rejecting the path of insiders. This creates a lone wolf persona with certain gifts: a heightened ability to walk alone, to see through group narratives, and to not feel chained by convention. We often end up self-taught (see, for example, Outsider Art), which sometimes helps us to see the world differently.

A lone wolf persona can emerge to protect that part of yourself that feels excluded, but it also doubles as a protective impulse towards all other underdogs. In any social situation, they stand out to me as if under a spotlight. That’s because, through outsider eyes, insiders often blend into a single mass. You can see them bound together by the euphoria of feeling included. You can see them partaking in the policing of the boundaries.

Outsiders might not require acceptance to operate, but that doesn’t mean we don’t still desire it. In fact, what often happens is that we use the gifts of our outsiderness to try gain some inclusion. For example, we might try to impress with our self-taught art-forms - like Kurt Cobain did - and, given that we may end up on a margins between groups, we have certain skills in building bridges (for example, by explaining the inside stories of each group to members of the other). We’re also quite adept at busting through the more smarmy forms of self-reinforcing insiderness that hold many groups together. This is how I came to be providing critiques of the progress narratives pumped out by digital corporate oligopolies.

Digital outsiderness

Over the last decade the fintech industry has risen to power. They cast physical cash as an unwanted outsider, and force-feed the world an inauthentic story about shiny digital convenience, innovation and win-win consumer benefit for all. They’re part of that class of paternalistic digital crack-dealers, talking about how the kids are so empowered by Instagram, Venmo and ApplePay as we all sink deeper into addiction.

I have an almost allergic reaction to their self-serving narrative, and I started deconstructing the standard stories around ‘cashlessness’ in 2015. My critique is multi-pronged (see 10 Reasons to Fight Cashless Contagion), but one strand of the critique focuses on the use of digital payments for surveillance and control. Unlike cash, digital payments can have conditions and restrictions placed on them, largely because they go through intermediaries - the card companies, banking sector and (fin)tech firms - who have the ability to monitor them, limit them or block them (or receive orders from a government to do that).

Over the years, I’ve been contacted by many people from all over the political spectrum who picture themselves as being the potential subjects of deliberate payments exclusion. Cutting off money, blocking transactions, and seizing wealth to prevent action is a pretty ancient phenomenon, but the most prominent modern form is economic sanctions. This is a mode of coercion sometimes used indiscriminately against entire movements or nations, regardless of whether their individual members are even involved in a conflict. If you’re a repressive political leader who wants to stamp out any nascent insurgency, it’s crucial to get opposition groups classified as terrorists so they get put on international sanctions lists. This ripples through into the transnational banking sector, who sometimes stop providing cross-border payments to entire sectors and population groups through a process euphemistically referred to as ‘de-risking’ (more accurately, financial strangulation).

At a more granular level, we know about the freezing of individual bank accounts of rich fraudsters, or political dictators, but this also happens to individual advocacy groups. For example, after it published Chelsea Manning’s leaks in 2010, the whistleblower site Wikileaks was subject to a blockade by VISA, MasterCard, PayPal, Bank of America and Western Union. Greenpeace had its Indian bank accounts frozen in 2015, on dodgy charges designed to stop them ‘stalling crucial development projects’ and ‘hurting the economy’. It was 2020, however, when the concern around payments censorship escalated to never-before-seen levels.

2020 was a year when our digital environment thickened and suddenly felt all-encompassing. This coincided with stronger-than-usual state directives, with stark restrictions on action. The fintech sector and retail chains used this opportunity to launch a massive campaign of totally bogus scaremongering about cash, claiming - or not-so-subtly implying - that it carried COVID. People were caught between the fear of the physical, and a suspicion of the digital, but in the confusion felt pushed into the arms of Big Fintech.

The concern escalated due to an obscure technical problem that accompanied this. The ‘cashless’ units in your account are like digital casino chips issued out by banks, and like all chips they derive much of their power from their redeemability back into cash (i.e. when you go to the ATM, you’re ‘cashing your digital chips’). Put differently, cashless systems are psychologically and legally anchored by the cash system, so the fact that the cash infrastructure was being undermined made central bankers fret. They began pondering about potential digital replacements for cash, which led to a spike in interest about ‘CBDC’ - central bank digital currency (see Zen and the Art of CBDC Analysis).

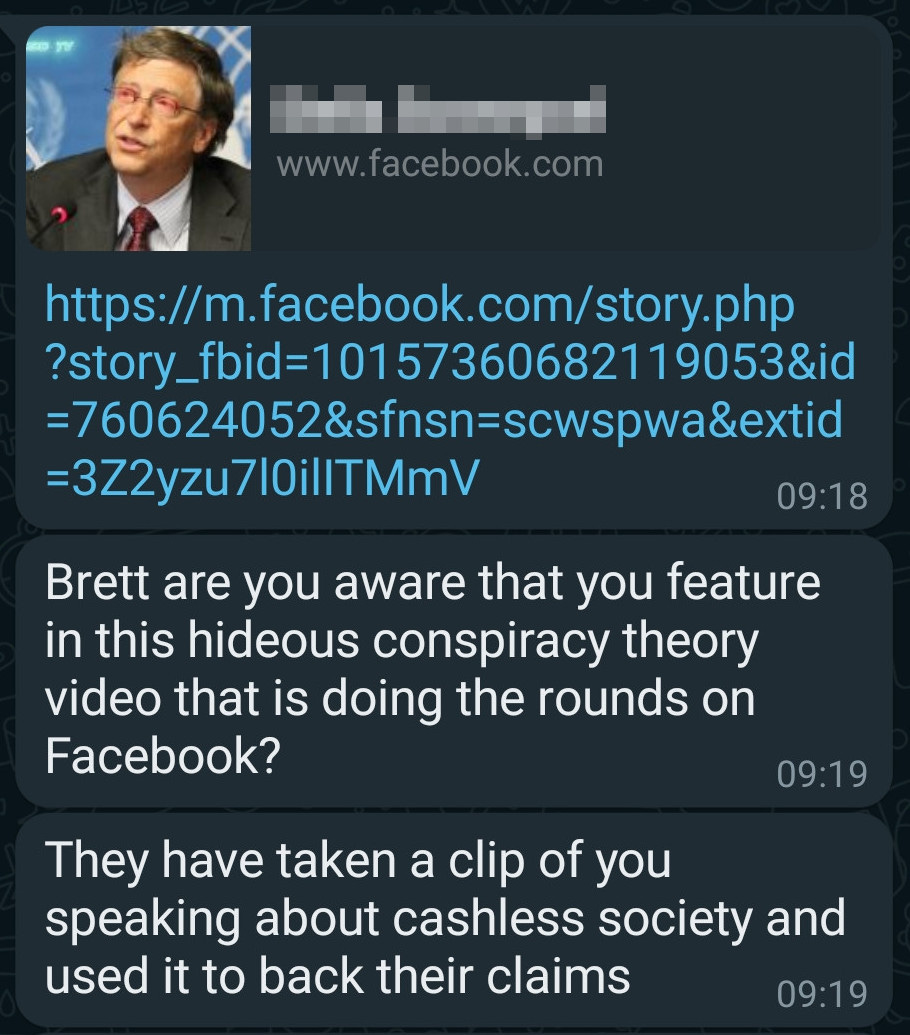

Most people aren’t trained in the underlying plumbing of the monetary system, so it was easy for them to get confused by this. Unsurprisingly then, I saw a big public up-tick in interest about my work on cash and digital payments. Many people were also concerned about whether restrictions could be placed on what they pay for, where, when and with whom? Their concern was legitimate, but I started to notice a distinct cultural skew in their language. A significant number of my new post-pandemic followers were beginning to reference common phrases and names, like ‘The Great Reset’, ‘plandemic’, Klaus Schwab, the WEF, and Augustin Carstens. I also noticed that conservative columnists like James Delingpole, and UKIP campaigner Douglas Carswell were retweeting my work. I had a right-wing Dutch politician enthusiastically promoting me. Then my mother alerted me to the fact that a clip of me was being used without permission in a viral video about how Bill Gates was orchestrating COVID to push a cashless society, so that he - and others - could control your spending and movement via digital payments.

By the time I saw that video it had over a million views. I was spliced in alongside a weird cast of rebels, including an apocalyptic preacher prophesying the coming anti-Christ in the form of microchipped cashless payments that represented the mark of the beast.

That guy was an extreme, but it’s definitely true that many people showing interest in my work were also getting drawn into conspiratorial vibes. Rather than analysing the cold impersonal forces of global capitalism, they imagined individual personalities like Bill Gates pulling the strings behind the scenes. Some commentators were referring to this growing cultural constellation as ‘conspiracy theorists’ and the ‘populist right’, but those labels weren’t accepted internally, and it was apparent that there were many disparate strands of people coming together to weave a unique identity. In fact, many believed their growing ranks transcended the traditional boundaries of Left and Right, and that they were a rebellious force representing The People versus The Elite. In due course I found a term for them that fit: ‘diagonalists': those who imagine themselves to be cutting through the staged battle between the centre left and centre right.

Core to the diagonalist self-image was a mainstream-busting aesthetic. They used all the words of heroic lone-wolf struggle against victimhood. They rejected suppression. They stood for freedom, free-thinking, the path less travelled, making up your own mind, ignoring experts, being contrarian, learning for yourself, breaking the rules, tearing down the establishment. They had various charismatic leaders rising to the fore, like Russell Brand, formerly an avowed socialist who was repositioning himself as a voice standing up against elite power more generally. He was joined by others from the right wing, and together they formed a growing class of opportunistic pundits who specialized in raising the alarm about looming digital totalitarianism. Within central banking circles, the debates around CBDC are dull and slow, but in the hands of people like Brand, it became a dystopian story about an imminent takeover of the digital money system by repressive state actors and oligarchs.

While I was supportive of the general uptick in pro-cash sentiment that these commentators were stoking, something was very wrong in their analysis. For a start, it’s the commercial banking sector that’s been undermining the cash system, and they’ve been doing payments surveillance and blocking for decades. Most banking CEOs don’t announce this fact. The various technocrats from central banking circles, by contrast, were blissfully ignorant about how their plumbing operations were being spun in the popular realm, and made the ill-advised decision to speculate about the ‘programmability’ of CBDC.

Programmability is just a buzzword for automated conditionality. Any digital system - regardless of whether it’s controlled by a state, a corporation or a community - can have conditions placed on its operations. There are many private-sector fintech firms that specialise in creating systems that can only be used by authorised people for specific things, with automatic triggers and blocks (for example, think about those apps that allow parents to control the digital spending of their kids). In the pandemic moment, however, amidst the fears stoked up by the punditry, I noticed that a large number of people were beginning to imagine that programmability was a unique property of state-run digital systems, rather than a general feature of almost every corporate platform that their lives currently depend on.

My outsider eyes were also picking up other glitches in the narrative. For example, I noticed that some people in this constellation had a habit of placing certain historically-marginalized groups within the scope of ‘The Elite’. Also, despite their references to breaking down mind-viruses and group-think, they showed many classic signs of group-think within their own ranks. Not only were they beginning to use the same language, but they were using the same examples to illustrate their talking points. For me, one stood out above all. The Canadian Truckers.

The selective curation of universal principles

The story of the Canadian Truckers is quite well-known now. In 2022, some people who worked in the Canadian trucking industry crowdfunded the Freedom Convoy, a protest initially against cross-border vaccine mandates. They blocked off down-town Ottawa with their trucks, and after two weeks the Ontario government declared that it was no longer a protest but an ‘illegal occupation’. This eventually led to their GoFundMe page being terminated, and the bank accounts of the organizers being frozen as part of an effort to stop them.

It’s obvious that there was a clash of world-views at play when Justin Trudeau decided to take action against the protest, and the growing diagonalist intelligentsia - which was now starting to include everyone from Jordan Peterson to Tucker Carlson, Naomi Wolf, Joe Rogan, Elon Musk and Bret Weinstein - all took up the Freedom Convoy cause. Russell Brand dedicated over ten videos to it on his channel, but I was also being asked to commentate on it. I received a spate of invitations to appear on ‘anti-mainstream’ news outlets who claimed to be broadcasting the truth that authorities and legacy media ‘don’t want you to know’. To some presenters, the Truckers seemed to represent a new and ominous portent about a totalitarian future that was coming to get us (or at least them).

There’s no doubt that the Freedom Convoy was subject to financial suppression via a digital payments infrastructure. It’s worth noting, however, that this is almost identical to the aforementioned actions taken against Wikileaks and Greenpeace. In all cases a protest group finds themselves shut down by authorities who say what they’re doing is illegal. These groups, plus many others across the world who’ve been labelled as terrorists, see themselves as victims of politically-motivated suppression. This is not new to me. In my own home country, opposition groups who asked for the most basic human rights - like the right to vote - had their assets frozen and were imprisoned as terrorists from the 1960s to the early nineties.

Many of the diagonalists, however, seemed to view the Truckers as an unprecedented one-of-a-kind instance, a wake-up call. To some extent this makes sense. After all, the Wikileaks case concerns a secretive global group with no obvious geographic location, while the Greenpeace case happened in faraway India, a country of relatively little interest to Western media. As for groups like the PKK in Turkey, Erdoğan gives his word that they’re baddies who use bombs (something the Turkish government would never dream of doing), so they just get written off.

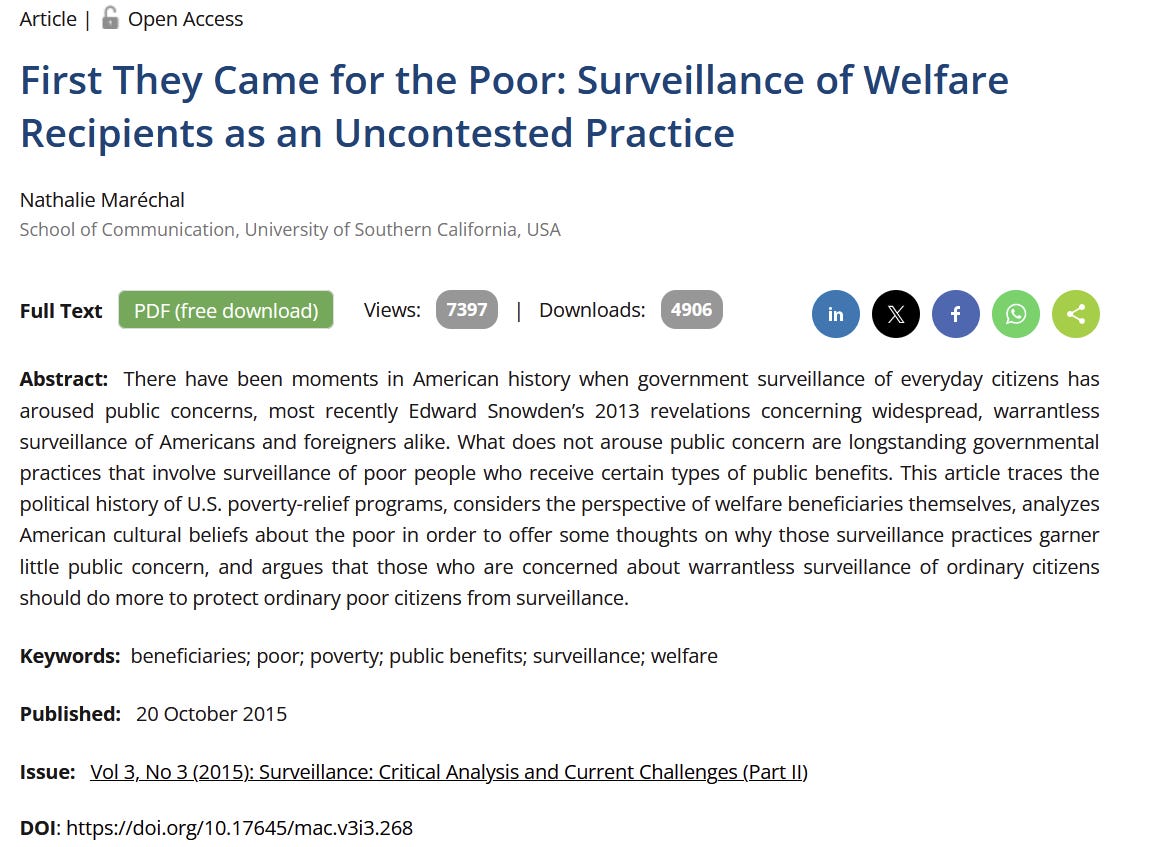

All these cases happen somewhere distant to a person in the US or Canada, so could it be that the Truckers struck a nerve because this was the first time that citizens of a democratic Western nation were subject to payments oppression? The answer is no. Cashless payments censorship has a long and established tradition in Western countries. It’s just that it’s not recognized because it’s been focussed on marginalized groups such as welfare recipients. The scholar Nathalie Maréchal, for example, has investigated how financial control of the poor has often been normalized on paternalistic grounds.

There are many reasons why a person might rely on welfare, from war disabilities through to single parenthood, sickness, depression and addiction. These situations are also often associated with people who’ve been structurally marginalized in their societies. In other words, they disproportionately affect groups on the outside edges of society, but the welfare system often ends up controlled from the inside by people who’ve seldom faced systemic outsiderness. Insiders like this are far more likely to casually believe the conservative memes about the poor being poor because they’re lazy, or because they lack initiative, impulse control and motivation. It might appear reasonable to them that welfare recipients should be monitored like little kids.

The earliest forms of payments ‘programmability’, then, have been welfare systems like the US food stamp programme. These operate via coupons that contain inbuilt conditions that limit their redeemability to certain things in certain places (while often having an explicit prohibition on the receiving of change in cash).

Sometimes this appears relatively benign. For example, in the early days of the pandemic, the small town of Tenino in Washington handed out ‘wooden dollars’ - dollar-denominated vouchers printed on wood - to people who were entitled to support grants. These vouchers were only redeemable in small local businesses, rather than in distant corporate behemoths like Amazon.com or Walmart. By limiting the redeemability of the vouchers like this, welfare recipients were corralled into spending locally, which could help create a local ‘multiplier effect’ that might boost local employment too, thereby killing two birds with one stone.

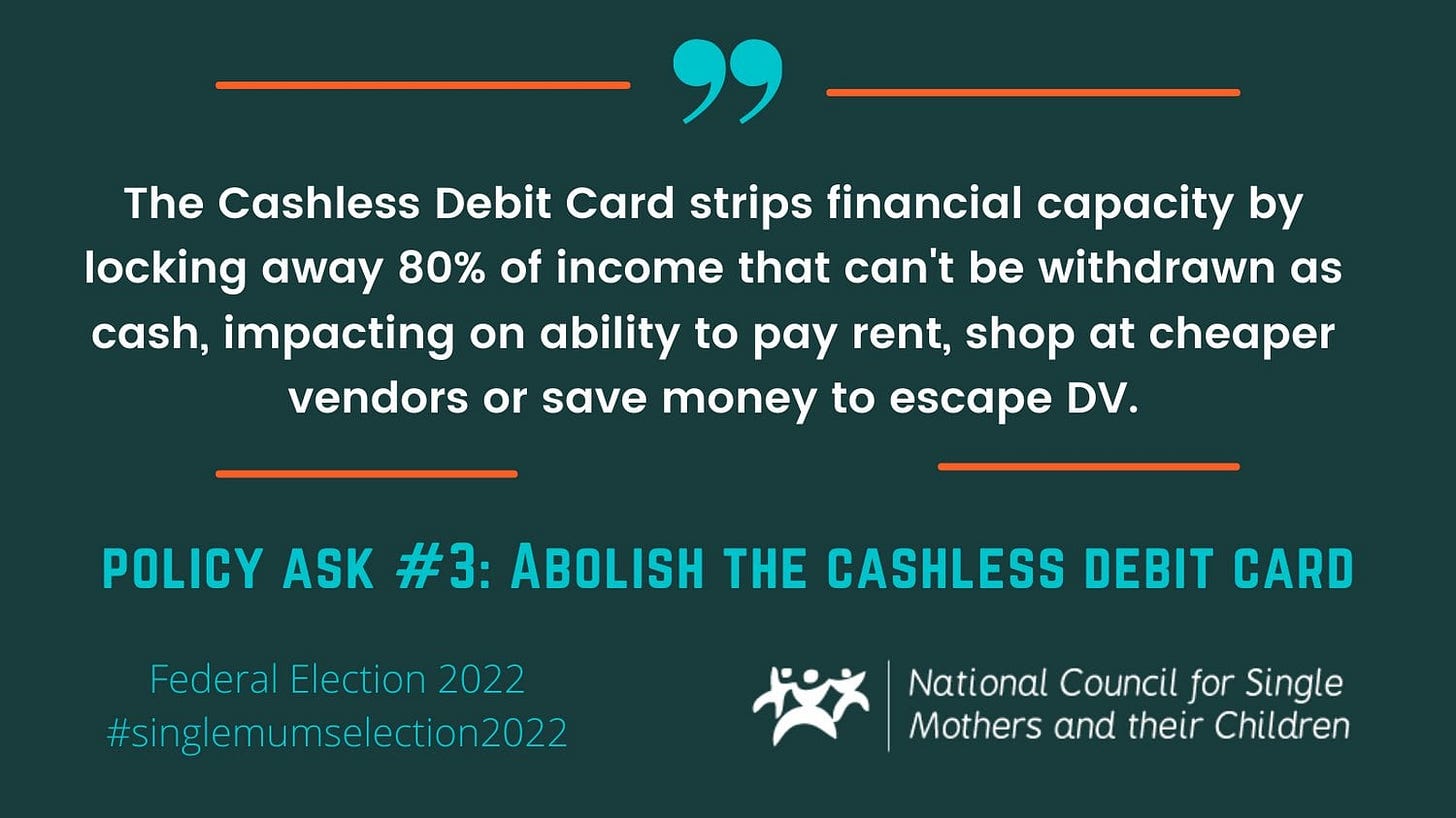

Much more controversial though, was the Australian Cashless Welfare Card, a VISA card scheme set in motion by members of the conservative government of Tony Abbot. It was explicitly designed to limit the spending choices of the poor - which disproportionately includes indigenous Aboriginal Australians - by blocking them from buying things like alcohol and cigarettes. This practice, and other restrictions, came disguised with paternalistic names like Enhanced Income Management, but community activists had a simpler name for the scheme: the ‘Class Warfare Card’.

The Cashless Welfare Card system worked primarily by blocking entire shops, but experiments with product-level blocking within approved shops have gone on too. Not only does this have the psychological effect of making adults feel like children, but it treats addiction problems as if they were bad choices made by deficient people, rather than emotional responses to having been made an outcast on your own territory. This same technology is now being applied to outcasts outside their own territory, such as refugees in Germany.

In 2022, the Cashless Welfare Card scheme was ended by the new Labour government in Australia, causing backlash from conservatives. Since then, the conservative newspaper The Australian has run no fewer than seven stories talking about the ‘chaos’ that has ensued since the paternalistic scheme has been ended, while Spectator Australia slammed the decision as based on ‘ideology, not reality’. Their message can easily be read as ‘We want payments control over indigenous Australians to be reinstated’.

When an Aboriginal person reads the newspaper called The Australian, do they feel like Australians at all? That publication also ran sympathetic stories about the Canadian truckers, but it’s worth asking how many members of the Freedom Convoy have ever spoken out on a couple centuries of financial and political silencing of indigenous Canadians. To some people, the image of The Trucker might be the image of a hard-working family man, but when an Anishinaabe women sees the protesters rolling past her reservation, is she filled with a sense of proud patriotism and inclusion, or is the feeling more complex? Indigenous Canadian researcher Krista Stelkia argues that the Freedom Convoy would have been shut down much quicker, and more violently, if they’d been a convoy of indigenous drivers.

Detachment styles

The Australian is torn on the issue of another Australian. Julian Assange. In 2010 his Wikileaks published the Collateral Murder video, in which a US helicopter crew guns down Arabic people while laughing as if it were a video game. Assange has become an ambiguous figure because he has markers of another outsider archetype: the mercenary.

Social outsiders certainly have the capacity to buy into causes, and to experience forms of inclusion, but they’re also relatively more able to detach from the insider dynamics of these groups. This may double as a less judgemental view on any apparent enemy of the group, which can give outsider-types a slightly mercenary edge (the wandering lone ranger resigned to a life of mercenary outsiderness is a popular film archetype, especially because they can be saved through love or inclusion).

Unlike a true zealot, the mercenary archetype doesn’t really hate the people they fight against. They might actually give you fairer treatment if you’re on trial in a domain controlled by a group you don’t belong to, but they can also pose a threat. Like Assange, they might reveal things a person likes - such as Hilary Clinton’s emails - but also things they don’t like, such as the war logs of an ally.

This is sometimes how I feel when I appear on the 'anti-mainstream' 'free thought' media outlets. They want to hear about the financial censorship of the Freedom Convoy, but they don’t want to hear about restrictions on Aboriginal payments. This hints to a skew in their freedom of thought, and it’s certainly not open-minded. When they approach me, they’re trying to recruit that mercenary side of me who is nominally prepared to defend their narrow free thinking, but this poses an ethical dilemma, because their selective curation of what examples of payments censorship they’re prepared to ask about or listen to amounts to a silent form of censorship in itself. Selectively hearing, and amplifying, one set of injured voices - the Truckers - can be very similar to blocking another set out.

But this is core to the diagonalist strategy. Their spiritual leaders, from Steve Bannon to Brand, first appeal to big universal concepts like The People, Justice, and Freedom, which supposedly have a pure meaning inscribed in the cosmic order. They then superimpose those over particular parochial concerns. So, Freedom is a universal principle written in the sky, but - more specifically - it’s The Canadian Truckers. By extension, Trudeau’s payments censorship is Repression, but Tony Abbot’s attack on Aboriginal payment freedom is mere Prudence. After all, what universal principles and archetypes do the aboriginals represent to those who will not listen to them? Addiction. Laziness. Entitlement. Losers. Outsiders. Weirdos.

All movements will spin universal principles like this into their narrow political programmes, but the diagonalists have done it in a particularly sneaky way. They’ve stocked their growing network of promoters with people who can credibly claim to represent both sides of the old political spectrum, like Russell Brand, and Naomi Wolf, who hate the idea that they might be right-wingers. Nevertheless, it’s obvious through their curation of examples that they’re veering rightwards. Brand is supposedly a working-class boy with a feel for the people, yet he isn’t talking about the Class Warfare Card, or the new requirements pushed out in the UK to monitor the bank accounts of welfare recipients.

Rather, he’s ranting about a hypothetical future state digital money system, which might hypothetically be used by Greta Thunberg to force you to buy low-carbon products. Brand himself might not make the latter claim directly, but it’s done by association through the diagonalist influencer universe, which operates like a social network of strange bedfellows. Many of them have made cynical political pivots to ride the diagonalist popularity train. For example, Richard Werner used to be an insightful critical voice on debunking mainstream economics. Now he’s selling cheap scare stories about micro-chip CBDC implants to his new audience, selectively noting how they could be used to force you into 15 minute cities, or police your carbon budget, while ignoring the stories of actually-existing payments censorship of groups his audience doesn’t resonate with.

Want to syndicate this essay? Contact me here

When outsiders cosplay insiderness for insiders cosplaying outsiderness

The sad thing about people like Brand is that he probably indeed is an outsider. He probably does experience an internal crying out for acceptance. So, he trades his principles off to be the centre of attention for a new group built around his wounded ego, one that turns him into a guru touched by some magical outsider light. A guru like this isn’t so much an insider as an enclosed outsider, captured by those who reflect his image back at him, comforting him.

But this position isn’t secure. There’s no shortage of new rising stars in the diagonalist attention economy, and Brand must feed his followers to keep their eyes on him. He must replicate his story, day-in-day-out, to keep his guru status. If he doesn’t, he might find himself dropped. Silenced.

Being thrown back into obscurity would probably liberate him from his followers, but right now he’s yoked into curating examples that make them feel like outsiders, because feeling like an outsider is a core part of their new identity. Let’s face it, one major reason the diagonalist movement has gained traction is because its gurus specialise in applying the language of outsiderness like a balm to those who wish to restore a sense of lost insiderness. At core, it’s a rebellion of the disenchanted white middle class, a group particularly prone to believing in all the old stories about being a self-made person in the free market. Many sense their position in the world is in a state of relative decline, and are drawn towards a kind of victim complex in which they imagine themselves as suppressed minorities. In fact, some literally start to believe they are like African slaves, persecuted Jews, or ostracised weirdos, as if the guy running the libertarian YouTube channel is like a Spinoza fearing for his life in the 17th century, or Nelson Mandela having his 1978 book banned in my home country.

This is what Naomi Klein calls doppelganger politics, a kind of mirroring, cosplaying, appropriation and mimicry of victimhood. The complexity, however, is that insiderness-outsiderness is a fluctuating spectrum, even within a person. On average, the diagonalists represent a radicalized middle of society that’s now cloaking itself in the image of those historically excluded, but averages hide many nuances. For example, a Welsh working class man might feel relatively marginalised within the UK, but at a global scale he’s actually part of middle class, given that he’s a citizen of a country with a lot more geopolitical and economic power than, say, my home country (where it’s not uncommon for the working class to live in hand-built tin shacks). This is one way in which diagonalism starts to capture a motley cross-ideological crew of people with different degrees of inclusion, but sharing a common sense of losing relative position. There are many old British left-wingers who care about fighting austerity programs and protecting welfare systems, but who’ve found themselves drawn into a cranky diagonalist rhetoric of rebellion that structurally skews to white social conservativism. This is how their eyes have fixed onto the censorship of the Canadian truckers, and why they’re clicking the like button on Russell Brand’s videos.

I started life as a shy voiceless one, but nowadays I try to hear and amplify silenced voices, but this still involves making judgements on who is truly silenced. This is what confronts me when I get approached by those seeking common cause with me on payments censorship. What do I say to someone who has come to believe that they have enemies suffering from a woke mind virus, and that these enemies will use CBDCs to police their carbon footprint, to prevent them buying meat, and to extend cancel culture into the realm of free transactions?

I’ll tell them five things. Firstly, yes, it’s very important to fight the general principle of payments censorship (and, by extension, to protect the cash system that provides a buffer agai nst it). Secondly, I must inform them that the actual chances of payments censorship being used against them is smaller than the chances of it being used against refugees, migrants, the homeless, or sex workers, who face recent real-world cases of financial censorship.

Thirdly, while I really do respect their concerns about hypothetical cases of their future victimhood, I must also reflect back to them the actual cases of present victimhood.

Fourthly, I must share that if woke is a mind virus, then so too is anti-woke. The imagined freeing of thought and action represented by the latter is really just the reassertion of one particular style of thought and action that was previously hegemonic. That takes us back to the social dynamics we began with, and to my fifth point: Hegemonic thought silences people, and makes them censor themselves , without any authority needing to resort to overt technologies of control. Actual free thinkers can see that quite easily.

Superb work. Thank you 🙏Unfortunately most diagonalists (love the term) will not get far in this but it certainly will help those that unexpectedly find themselves adjacent to them.

A great nuanced analysis of how the dynamics of our relationship to others influences our take on events we haven't actually experienced ourselves. I was all but celebrating my new-found status as a diagonalist until I read on...

As a lone wolf myself I am nevertheless drawn to the crowd while permanently hovering on its edges. There is a fear of being swallowed up. The promise of human warmth turning into suffocation. The perspective of being on the outside is so valuable but consigns you to a relatively lonely road. Small gatherings are more manageable than large crowds but we live in a world which is pushing us all into larger groupings beyond our villages and towns and even nations.

This is my problem with tech generally and fintech in particular. It is a way of attempting to manage larger and larger groups but with none of the finesse of personal interaction. It has a host of weaknesses that can be used by the ruthless and the more 'safeguards' that are appended the greater the power conferred on those who control them.

There is an obsession with 'making things better' ('Faster not Better') as if mere human interaction could not be the pinnacle of our humdrum lives. What could make our lives much less humdrum is turning away from our slavish adherence to the structures built with our clever tools and a better appreciating what we have had in abundance for centuries - if not millennia - what remains of the beautiful life around us and the warmth of true connection with others.