The Ten Layers of Finance

Understanding the world's most powerful industry, from sunlight to securitization

In today’s piece I reveal ten layers that make up the financial system. Paying subscribers get all ten. Free subscribers get the first four. Enjoy!

There’s a quick and dirty method to figure out where a layer sits in a stack of layers. You simply ask yourself what would happen to the other layers if this one were removed.

For example, let’s imagine the earth’s ecosystems as a layer. If this layer were taken away, the entire economic system would crash, and along with it the financial system. If, however, the financial system disappeared, the earth’s ecosystems would continue on as normal.

Conclusion: the financial sector is built upon ecosystems, not the other way around.

We can do this with industries too. If all farm workers stopped working for a week, every society in the world would begin to collapse. If financial traders stopped working for a week, many people wouldn’t even notice.

Conclusion: finance is built upon agriculture.

Of course it’s more complex than that nowadays, given that we live in a global economy in which the layers are inextricably entangled. Large-scale commercial agriculture, for example, is deeply entwined with financial markets, and can be heavily disrupted if the latter fail. Nevertheless, when push comes to shove, we want the farmers before we want the bankers. Farms are more foundational than hedge funds.

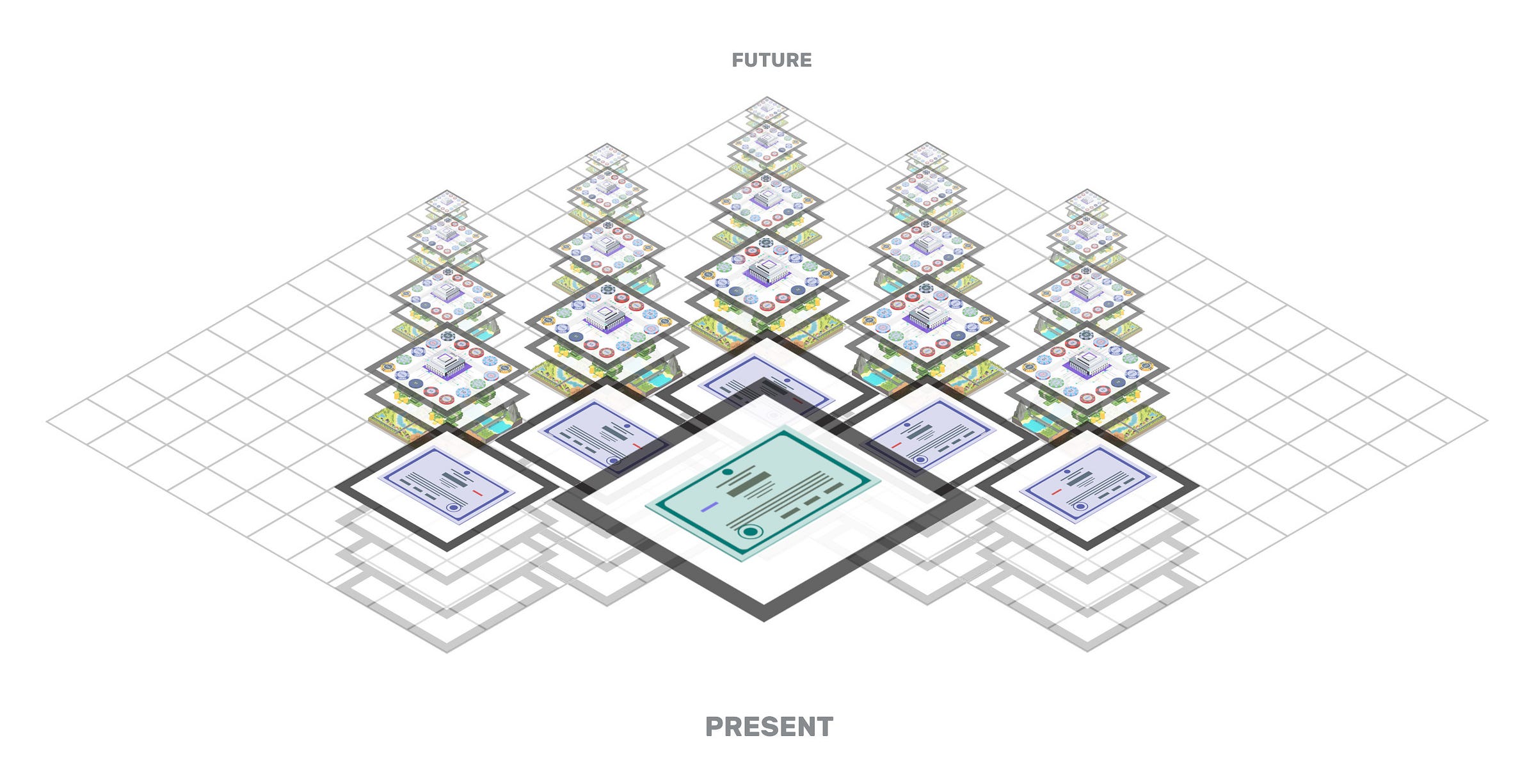

Finance itself, though, is not a single layer. Rather, it’s built from simpler foundations and abstracted upwards into progressively more complex forms. In this piece I’m going to show you ten layers of finance from the ground up. I’ll begin each layer with a one-line summary of how you get to it, and a description of the thing you hold once there. Let’s begin.

Layer 0: Value

Summary: you apply your body to the earth, alongside others, to produce stuff

You now hold: value

Send your mind 50,000 years into the past. There are human beings collaborating with each other to survive on the earth. This is the most primal layer of any economic system, and it always will be.

50,000 years ago nobody was talking about an abstract realm called ‘the economy’, and nobody cared about concepts like GDP, money, unemployment, inflation or free trade.

The only thing that matters to someone at that time are the people around them, and the environment they are in.

Within that environment, the only two distinctions that matter are things that require effort to get, and things that don’t.

For example, they - like us - get infinitely valuable sunlight and air without having to exert effort. It’s not something that needs to be planned for, rationed, or apportioned.

There are, however, other things like food, shelter and clothing that require them to apply their limited energy to the limited environment. They need to search for stuff, create stuff and secure stuff. There’s also a whole bunch of stuff they do for each other, like grooming, caring and cooking. To get and perform all this stuff, people use bodily energy, or labour (whether than be physical, mental or emotional), alongside other forms of energy like sunlight and fire.

Let’s just call these products of exertion value.

Once created, value needs to be apportioned, rationed, or distributed. They need to figure out who gets what and when under which conditions.

There’s no cosmic rule-book for how this should happen. An ancient hunter-gatherer band, for example, might communally distribute tasks, and communally share most products that emerge from those tasks, while having forms of subtle tit-for-tat reciprocity weaving through that over time. Maybe minor forms of explicit trade occur on the margins, but maybe not. A nomadic pastoral society, or a feudal society, or a 12th century religious commune will have different ways of arranging the same thing.

Let’s now fast-forward into the modern era. We have the same situation - a network of people drawing upon the earth - but now that network is unbelievably huge, and has been iterating upon itself for thousands of years. The products, technologies and techniques of former generations are now inputs, or foundations, to the products of current generations.

We, like hunter-gatherers, still face the same need to distribute and apportion this value, but nowadays a large chunk of that happens via market processes built upon money and finance. The earth and its people are covered by a web of tokens and contracts that distribute present and future claims upon the outcomes of production. Let’s go into it.

Layer 1: Base Money

Summary: you hand over value for a claim upon value

You now hold: a claim upon value

For the purposes of this article I’m going to ignore a bunch of complexity about the structure of money, and reduce it to the following phrase: money is a claim upon value.

Money is often metaphorically imagined like a commodity in itself - as if it were a ‘substance of value’ - but this is misleading. Functionally, at the level of our everyday lives, a unit of money is something that enables you to claim goods and services from other people (who are, either directly or indirectly, drawing upon the earth’s ecosystems).

Holding money is a bit like holding an access token to a vast warehouse of goods and services from others. In the case of goods, the stuff has already been produced. In the case of services, it has yet to be produced. Money can give access to the former and induce the latter.

Here’s a metaphor to help you understand this. Think about a simple voucher for a supermarket. The voucher enables you to access the supermarket and claim stuff. If the supermarket is destroyed, the voucher is rendered useless. If, by contrast, the voucher is destroyed, the supermarket remains, but there is one less claim upon it.

Similarly, if you burn a dollar bill, the underlying value residing within the earth and its people remains. But if the underlying people and ecosystems are destroyed, the dollar bill is rendered meaningless. A dollar bill has power to command things in our current world, but if a space adventurer crashed upon an alien planet, and found themselves stranded, a bill in their pocket would be a claim upon nothing. They’d have to ditch it, and focus upon the Layer 0 of their new environment.

So, at a very basic level, money acts as a contingent and transferable claim upon the goods and services produced by the labour power of other people in the context of our planet, and pushing it out and around can induce those people to produce things.

What I’m describing here is a kind of ‘horizontal’ view of money. It’s the view of it from a street level, where it enables you to get stuff from the random strangers who pass you by.

That said, I’m not describing the process of how such a claim is built and maintained. If you’d like to grapple with that, see my Global Money Observatory section, or my recent video on MMT, or my piece The Global Money System in 10 Images. In that latter piece, I visualise the ‘vertical’ dimension of money, the big institutional players that enable the horizontal action to occur.

The primary institutional player that issues our base money is the state, but state-issued money becomes the foundation for other forms of money, so let’s move on.

Layer 2: Bank-Money

Summary: you hand over base money for a claim upon base money

You now hold: claims upon [claims upon value]

When you hold Layer 1 base money, you’re holding a politically-backed and socially networked claim on the productive power of society within ecosystems. But, it’s not the only form of money we can hold.

In fact, most of our money nowadays takes the form of bank-money. That’s what the fintech bros call ‘cashless’. It’s the money we use when making card payments or bank transfers. It’s best thought of as bank-issued digital casino chips.

I’m not going to delve deeply into this, because I write about it in many other pieces (see The Casino Chip Society, and Paymentspotting). The basic deal though, is that banks issue a second layer of money into our society, and there are two basic situations in which they do this.

You go to a bank and hand over cash. You see the cash disappear and a number appears in your account. They essentially issued you a digital ‘casino chip’, which is what you now see in your account. You handed over base money to them, and got a claim upon base money in return

A similar thing happens when you walk up to a bank and ask for a loan. They don’t hand you base money. They issue you new chips, and extract a promise from you in return (to explore this, see Banks create money, but how do you explain this to the public?)

Regardless of the circumstances under which these digital ‘casino chips’ are issued, they are redeemable for base money (e.g. when you go to an ATM, you’re handing them back to get cash) but they’re also usable as money in themselves.

A huge amount of payments in our society take the form of people passing these chips between themselves within the bank payments system. That’s what’s happening every time someone beeps their card or Apple Pay app on a payment terminal, or makes any form of bank transfer.

Functionally then, bank-issued money ends up acting much like state-issued money - I can use it to claim stuff from the storehouse of human production - but if I’m being technically and pedantically accurate, their purchasing power is built upon that foundation of Layer 1 base money, so let’s call them claims upon [claims upon value].

Layer 3: Basic financial instruments

Summary: you hand over bank-money for claims upon future bank-money

You now hold: claims upon future (claims upon [claims upon value])

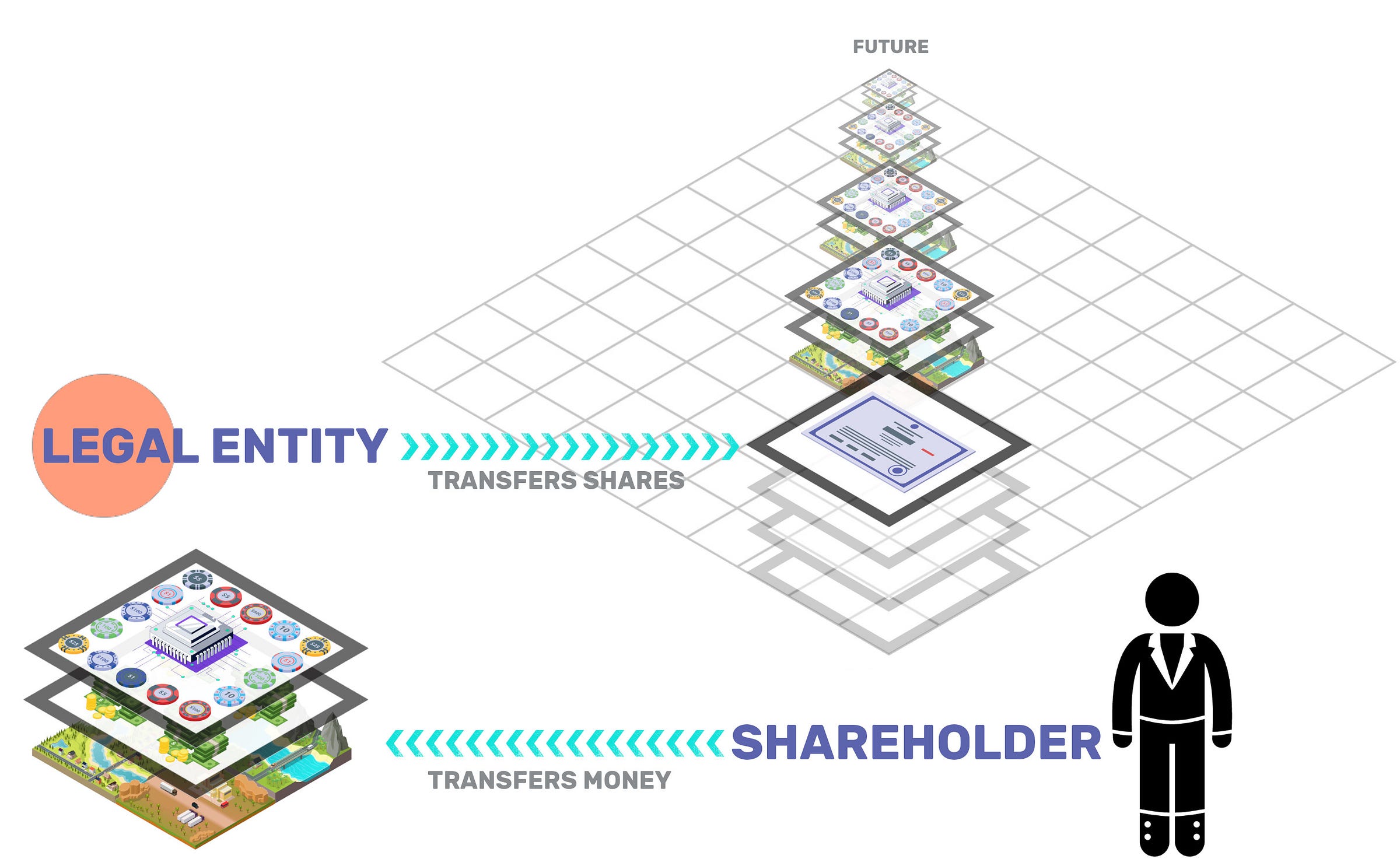

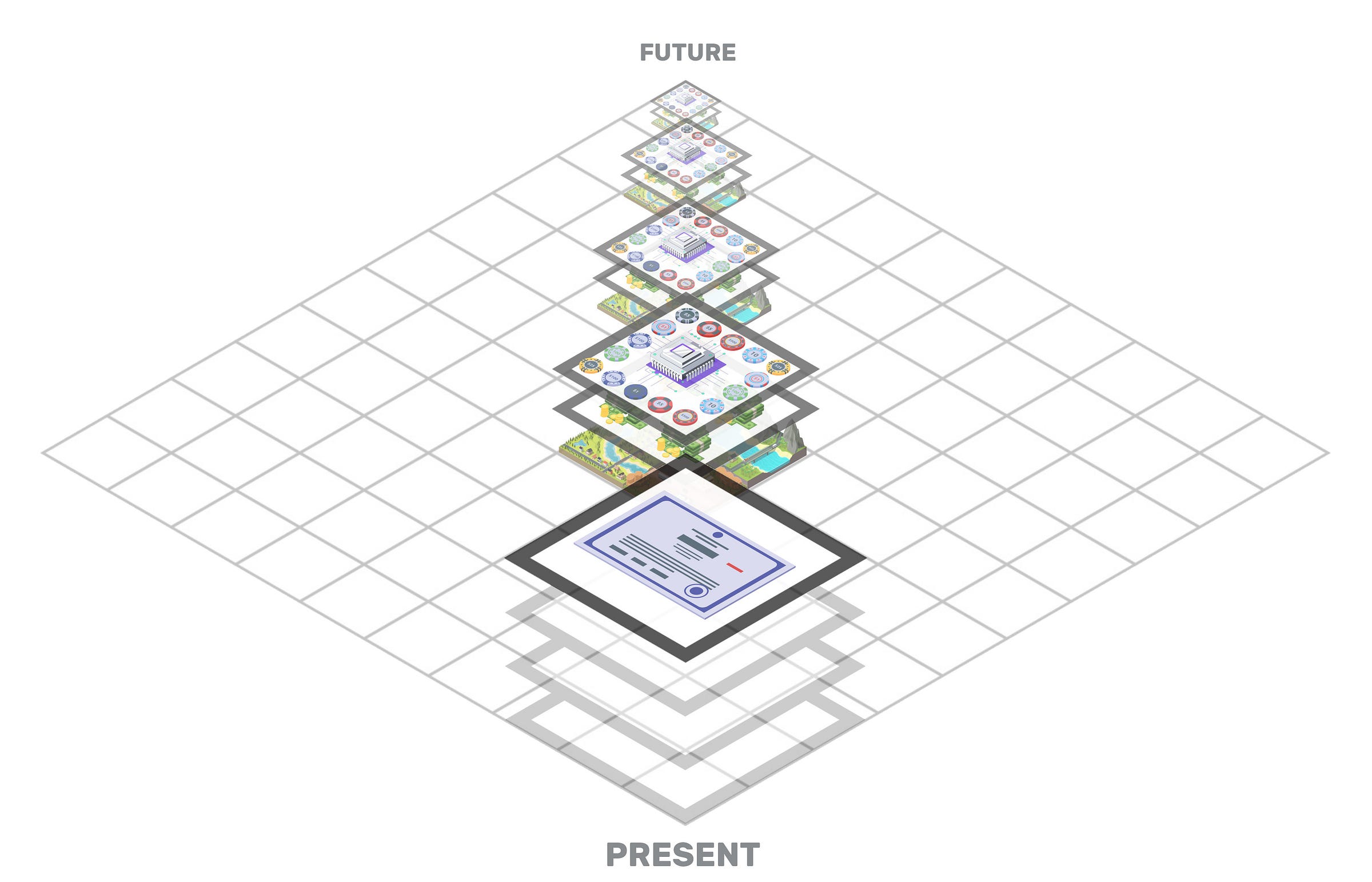

When someone starts a small business, they set up a legal entity with its own bank account, and then ‘capitalize’ it by transferring bank-money to it. The money goes from their personal account and into the account of the new legal entity.

In return, the legal entity sends them shares of ownership, which allows the holder to both control the legal entity, and to claim the profits of its future activities.

In essence, the shareholder buys the soul of the company, handing over money now in exchange for a legal instrument that gives them claims upon money emerging from the entity in future.

A share is called a share because it allows the holder to claim a share of the future profits that may, or may not, emerge from the entity. If they’re the only shareholder, they get to claim 100%. If they have partners, they may have a lower percentage.

If those profits emerge in future, they can be turned into dividends that will be returned back to the shareholder (or shareholders). That will manifest in the payments system as money being transferred back from the company’s bank account into the account of the shareholder.

Let’s look at another basic financial instrument.

Imagine a wealthy merchant giving a loan to a young associate to help them start a business. Money goes from the merchant’s bank account into the associate’s, and in return the merchant extracts a legal promise that the money will be returned with interest at some point in future.

When you study the money movements, you’ll see that they’re similar to those of a share: a person hands over money now in exchange for a legal instrument that gives them claims upon money in future. The primary difference, though, is that the amount due in future is fixed and predictable, rather than fluctuating and unpredictable.

So, a share gives a fluctuating claim upon future money emerging from an entity, while a loan, or bond, gives a fixed claim upon the same thing. You can combine these two primal forms into all manner of cocktails. In fact, you can even make one turn into the other, but we’ll have to wait for Layer 8 to see that.

Layer 4: Corporate shares and bonds

Summary: you hand over bank-money for a claim upon a federated network of basic financial instruments

You now hold: claims upon a network of {Claims upon future (claims upon [claims upon value])}

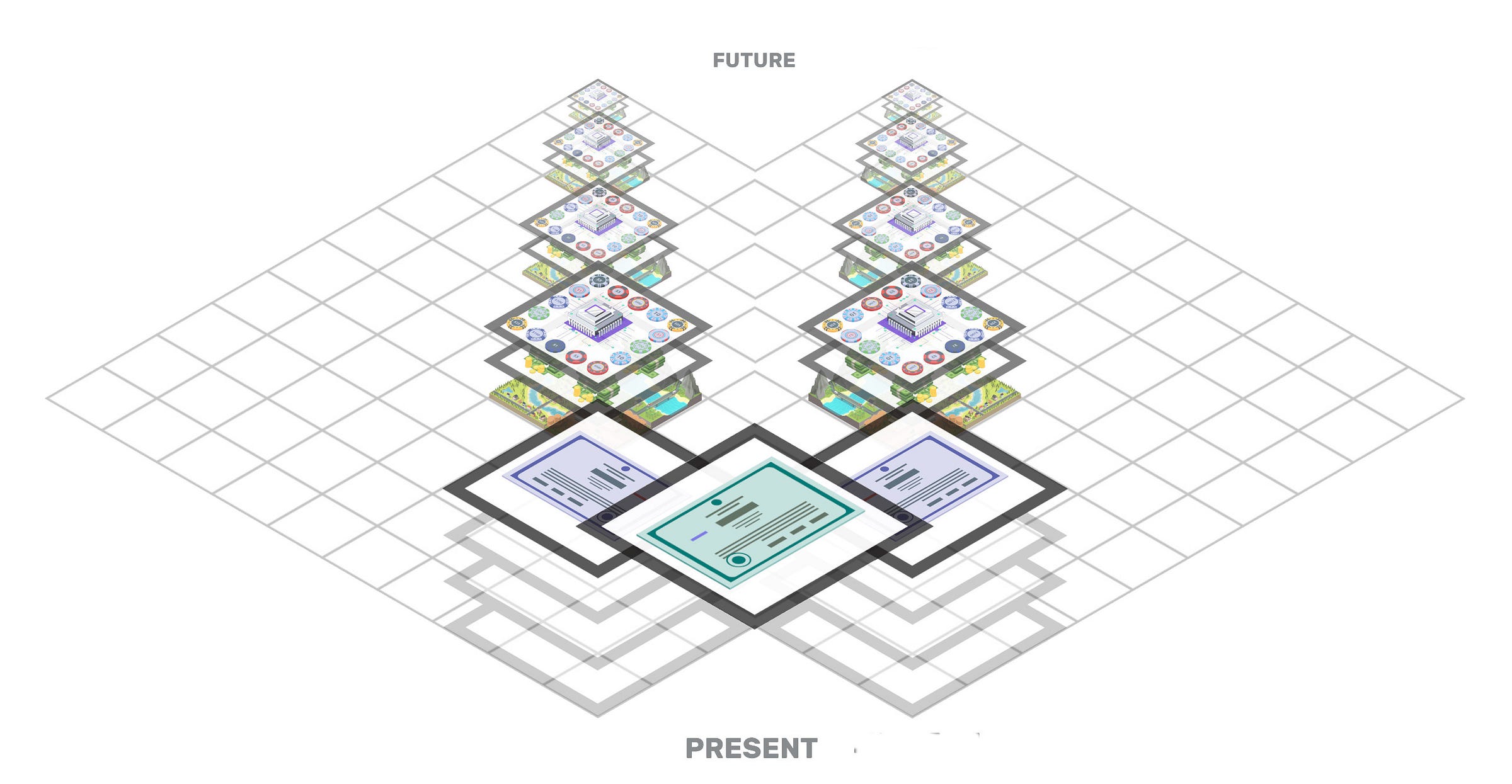

Let’s say that the two small businesses mentioned above get bought out by a bigger business. What happens is that the bigger entity transfers money to buy the shares of the smaller entities, incorporating them as kids - or subsidiaries - underneath a parent company.

A person who hands over money to get a share in such a parent company, will now be buying a stake in a three-company network, with the two smaller ones nested under the bigger one.

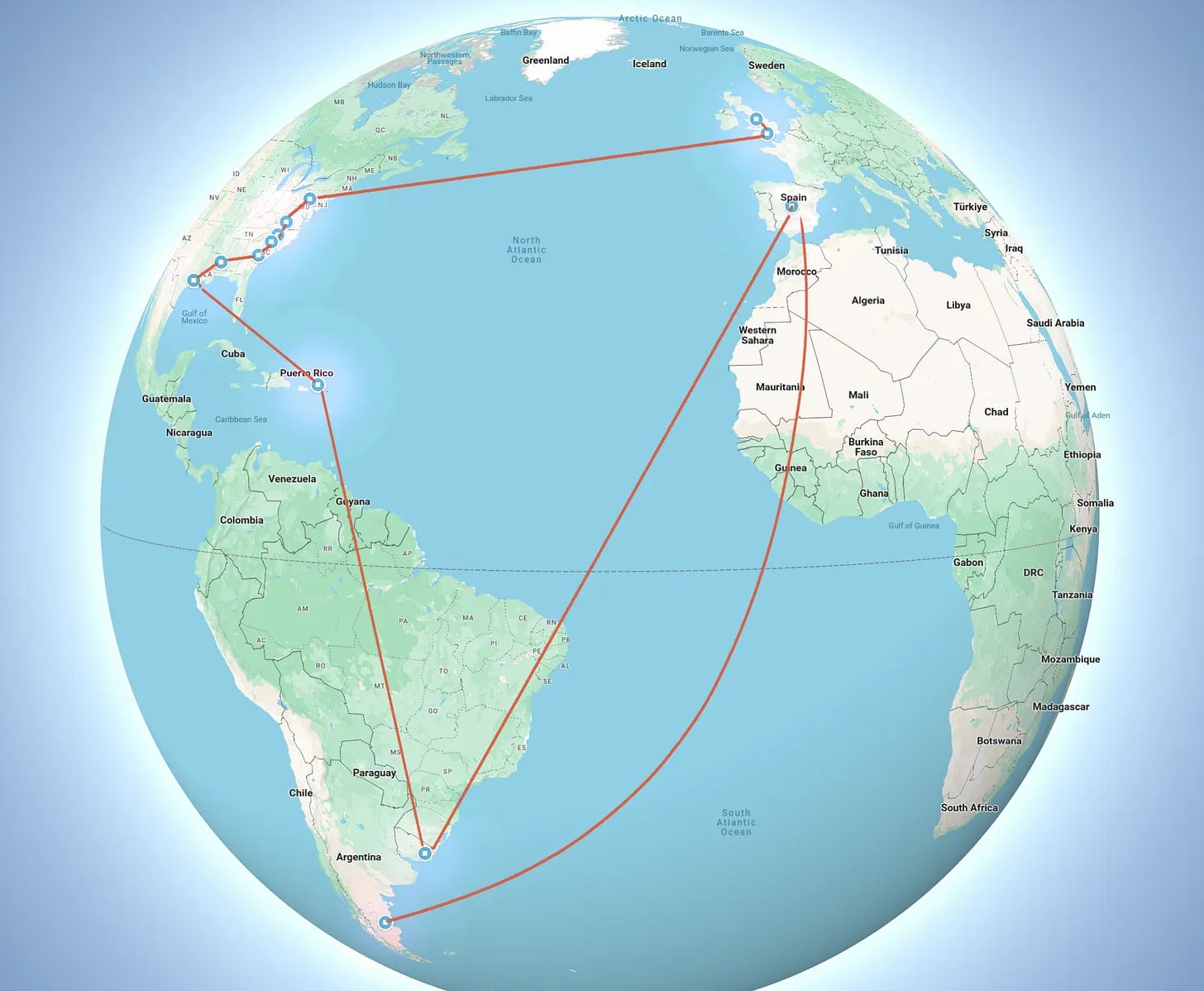

This is what a modern corporation is. In my Lego Model of Capitalist Central Planning, I show how a modern corporation is built from a federation of subsidiaries held under a parent company. Buying shares in the mothership gives you a claim upon its profits, but the mothership is in turn extracting profits from hundreds of subsidiaries across the world.

For the purposes of our visualisation, let’s have a corporation with five subsidiaries, but bear in mind that this could easily be fifty subsidiaries, or five hundred subsidiaries, too.

The biggest simplification I’m making here is to present the subsidiaries as being a single layer in themselves, when in reality a corporation can have subsidiaries that own other subsidiaries that own other subsidiaries. In the aforementioned piece, I visualise this process of creating chains of sub-companies, and I also show how the oil giant BP has been known to create chains twelve layers deep, with a mothership in London owning an outpost in Patagonia via a string of subsidiaries held together by financial instruments.

So, while I’m characterising corporations as a Layer 4 system, this layer could well be seen as having many layers within itself too (4.1, 4.2, 4.3 etc).

Modern corporations capitalize their subsidiaries by sending money to buy up their shares, but also by lending to them. This means they can extract money back from the subsidiaries in the form of both dividends and interest, and this can be useful when trying to run transnational systems of tax avoidance. For example, they might use their UK mothership company to capitalize a Cayman Islands one, which in turn passes the money as a loan to a Zambian one owned by their US subsidiary which in turn is owned by their UK one.

This stuff can get helluva complicated very fast, so let’s round this off by concluding that holding a share in a corporation gives you a fluctuating claim upon a tangled and federated network of subsidiaries held together by other financial instruments. If you hold a corporate bond, you’re getting a fixed claim on the same thing.

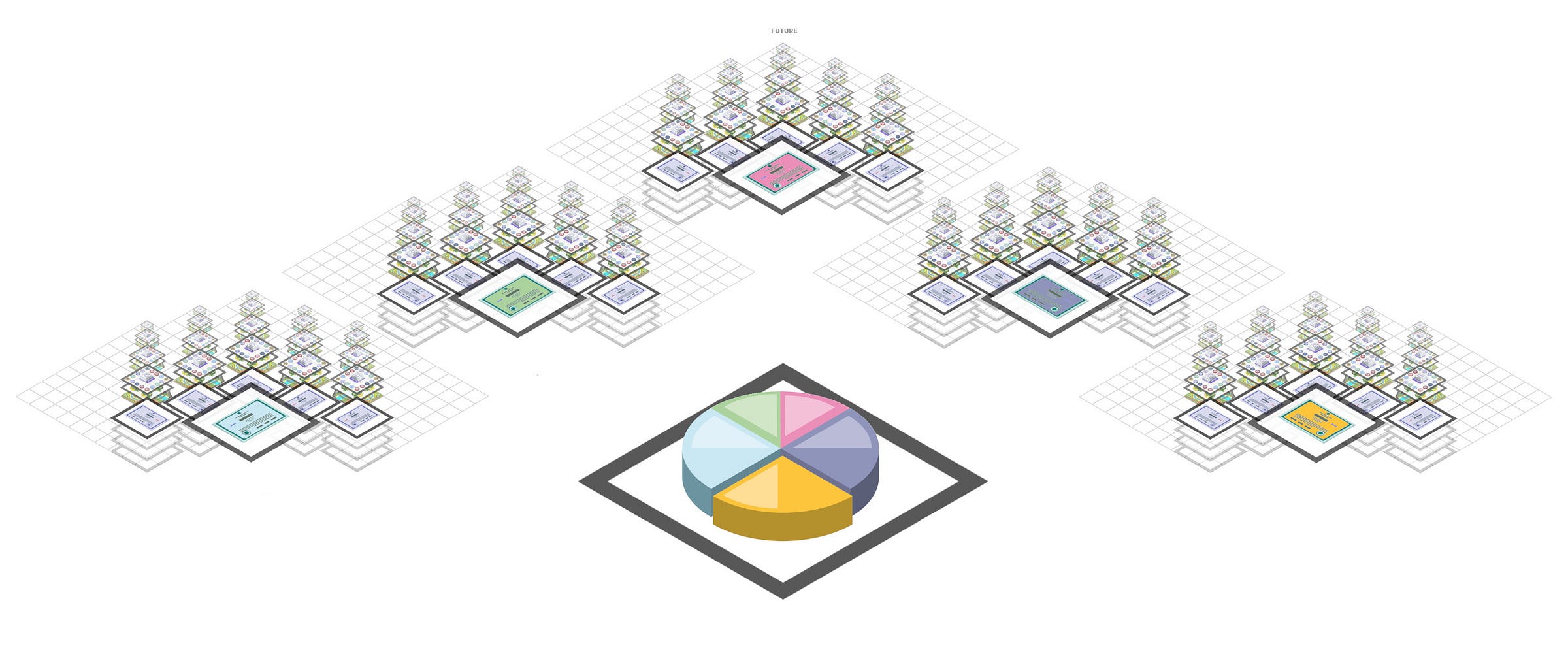

Layer 5: The Fund

Summary: you hand over bank-money for a claim upon a portfolio of corporate shares and bonds

You now hold: claims upon multiple [Claims upon a network of {Claims upon future (claims upon [claims upon value])}]